Best Timing for Measuring Orthostatic Vital Signs?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Advanced Interpretation of Adult Vital Signs in Trauma William D

Advanced Interpretation of Adult Vital Signs in Trauma William D. Hampton, DO Emergency Physician 26 March 2015 Learning Objectives 1. Better understand vital signs for what they can tell you (and what they can’t) in the assessment of a trauma patient. 2. Appreciate best practices in obtaining accurate vital signs in trauma patients. 3. Learn what teaching about vital signs is evidence-based and what is not. 4. Explain the importance of vital signs to more accurately triage, diagnose, and confidently disposition our trauma patients. 5. Apply the monitoring (and manipulation of) vital signs to better resuscitate trauma patients. Disclosure Statement • Faculty/Presenters/Authors/Content Reviewers/Planners disclose no conflict of interest relative to this educational activity. Successful Completion • To successfully complete this course, participants must attend the entire event and complete/submit the evaluation at the end of the session. • Society of Trauma Nurses is accredited as a provider of continuing nursing education by the American Nurses Credentialing Center's Commission on Accreditation. Vital Signs Vital Signs Philosophy: “View vital signs as compensatory to the illness/complaint as opposed to primary.” Crowe, Donald MD. “Vital Sign Rant.” EMRAP: Emergency Medicine Reviews and Perspectives. February, 2010. Vital Signs Truth over Accuracy: • Document the true status of the patient: sick or not? • Complete vital signs on every patient, every time, regardless of the chief complaint. • If vital signs seem misleading or inaccurate, repeat them! • Beware sending a patient home with abnormal vitals (especially tachycardia)! •Treat vital signs the same as any other diagnostics— review them carefully prior to disposition. The Mother’s Vital Sign: Temperature Case #1 - 76-y/o homeless ♂ CC: 76-y/o homeless ♂ brought to the ED by police for eval. -

Cardiovascular Assessment

Cardiovascular Assessment A Home study Course Offered by Nurses Research Publications P.O. Box 480 Hayward CA 94543-0480 Office: 510-888-9070 Fax: 510-537-3434 No unauthorized duplication photocopying of this course is permitted Editor: Nurses Research 1 HOW TO USE THIS COURSE Thank you for choosing Nurses Research Publication home study for your continuing education. This course may be completed as rapidly as you desire. However there is a one-year maximum time limit. If you have downloaded this course from our website you will need to log back on to pay and complete your test. After you submit your test for grading you will be asked to complete a course evaluation and then your certificate of completion will appear on your screen for you to print and keep for your records. Satisfactory completion of the examination requires a passing score of at least 70%. No part of this course may be copied or circulated under copyright law. Instructions: 1. Read the course objectives. 2. Read and study the course. 3. Log back onto our website to pay and take the test. If you have already paid for the course you will be asked to login using the username and password you selected when you registered for the course. 4. When you are satisfied that the answers are correct click grade test. 5. Complete the evaluation. 6. Print your certificate of completion. If you have a procedural question or “nursing” question regarding the materials, call (510) 888-9070 for assistance. Only instructors or our director may answer a nursing question about the test. -

(June 2000) I. INTRODUCTION WHAT IS DOCUMENTATION and WHY

DRAFT EVALUATION & MANAGEMENT DOCUMENTATION GUIDELINES (June 2000) I. INTRODUCTION WHAT IS DOCUMENTATION AND WHY IS IT IMPORTANT? Medical record documentation is required to record pertinent facts, findings, and observations about an individual's health history including past and present illnesses, examinations, tests, treatments, and outcomes. The medical record chronologically documents the care of the patient and is an important element contributing to high quality care. The medical record facilitates: · the ability of the physician and other health care professionals to evaluate and plan the patient's immediate treatment, and to monitor his/her health care over time. · communication and continuity of care among physicians and other health care professionals involved in the patient's care; · accurate and timely claims review and payment; · appropriate utilization review and quality of care evaluations; and · collection of data that may be useful for research and education. An appropriately documented medical record can reduce many of the "hassles" associated with claims processing and may serve as a legal document to verify the care provided, if necessary. WHAT DO PAYERS WANT AND WHY? Because payers have a contractual obligation to enrollees, they may require reasonable documentation that services are consistent with the insurance coverage provided. They may request information to validate: · the site of service; · the medical necessity and appropriateness of the diagnostic and/or therapeutic services provided; and/or · that services provided have been accurately reported. II. GENERAL PRINCIPLES OF MEDICAL RECORD DOCUMENTATION The principles of documentation listed below are applicable to all types of medical and surgical Pg. 1 services in all settings. For Evaluation and Management (E/M) services, the nature and amount of physician work and documentation varies by type of service, place of service and the patient's status. -

GUIDELINES for WRITING SOAP NOTES and HISTORY and PHYSICALS

GUIDELINES FOR WRITING SOAP NOTES and HISTORY AND PHYSICALS by Lois E. Brenneman, M.S.N, C.S., A.N.P, F.N.P. © 2001 NPCEU Inc. all rights reserved NPCEU INC. PO Box 246 Glen Gardner, NJ 08826 908-537-9767 - FAX 908-537-6409 www.npceu.com Copyright © 2001 NPCEU Inc. All rights reserved No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner whatever, including information storage, or retrieval, in whole or in part (except for brief quotations in critical articles or reviews), without written permission of the publisher: NPCEU, Inc. PO Box 246, Glen Gardner, NJ 08826 908-527-9767, Fax 908-527-6409. Bulk Purchase Discounts. For discounts on orders of 20 copies or more, please fax the number above or write the address above. Please state if you are a non-profit organization and the number of copies you are interested in purchasing. 2 GUIDELINES FOR WRITING SOAP NOTES and HISTORY AND PHYSICALS Lois E. Brenneman, M.S.N., C.S., A.N.P., F.N.P. Written documentation for clinical management of patients within health care settings usually include one or more of the following components. - Problem Statement (Chief Complaint) - Subjective (History) - Objective (Physical Exam/Diagnostics) - Assessment (Diagnoses) - Plan (Orders) - Rationale (Clinical Decision Making) Expertise and quality in clinical write-ups is somewhat of an art-form which develops over time as the student/practitioner gains practice and professional experience. In general, students are encouraged to review patient charts, reading as many H/Ps, progress notes and consult reports, as possible. In so doing, one gains insight into a variety of writing styles and methods of conveying clinical information. -

Chief Complaint: "Swelling of Tongue and Difficulty Breathing and Swallowing"

Chief Complaint: "swelling of tongue and difficulty breathing and swallowing" History of Present Illness: 77 y o woman in NAD with a h/o CAD, DM2, asthma and HTN on altace for 8 years awoke from sleep around 2:30 am this morning of a sore throat and swelling of tongue. She came immediately to the ED b/c she was having difficulty swallowing and some trouble breathing due to obstruction caused by the swelling. She has never had a similar reaction ever before and she did not have any associated SOB, chest pain, itching, or nausea. She has not noticed any rashes, and has been afebrile. She says that she feels like it is swollen down in her esophagus as well. In the ED she was given 25mg benadryl IV, 125 mg solumedrol IV and pepcid 20 mg IV. This has helped the swelling some but her throat still hurts and it hurts to swallow. Nothing else was able to relieve the pain and nothing make it worse though she has not tried to drink any fluids because of trouble swallowing. She denies any recent travel, recent exposure to unusual plants or animals or other allergens. She has not started any new medications, has not used any new lotions or perfumes and has not eaten any unusual foods. Patient has not taken any of her oral medications today. Surgical History: s/p vaginal wall operation for prolapse 2006 s/p Cardiac stent in 1999 s/p hystarectomy in 1970s s/p kidney stone retrieval 1960s Medical History: +CAD w/ Left heart cath in 2005 showing 40% LAD, 50% small D2, 40% RCA and 30% large OM; 2006 TTE showing LVEF 60-65% with diastolic dysfunction, LVH, mild LA dilation +Hyperlipidemia +HTN +DM 2, last A1c 6.7 in 9/2005 +Asthma/COPD +GERD +h/o iron deficiency anemia Social History: Patient lives in _______ with daughter _____ (919) _______. -

Emergency Department Chief Complaint and Diagnosis Data to Detect Influenza-Like Illness with an Electronic Medical Record

UC Irvine Western Journal of Emergency Medicine: Integrating Emergency Care with Population Health Title Emergency Department Chief Complaint and Diagnosis Data to Detect Influenza-Like Illness with an Electronic Medical Record Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/9gq782tz Journal Western Journal of Emergency Medicine: Integrating Emergency Care with Population Health, 11(1) ISSN 1936-900X Authors May, Larissa S Griffin, Beth Ann Bauers, Nicole Maier et al. Publication Date 2010 License https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ 4.0 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Original research Emergency Department Chief Complaint and Diagnosis Data to Detect Influenza-Like Illness with an Electronic Medical Record Larissa S. May, MD, MS* * The George Washington University, Department of Emergency Medicine, Beth Ann Griffin, PhD† Washington, D.C Nicole Maier Bauers, MS‡ † RAND Corporation, Center for Domestic and International Health Security, Arvind Jain, MS† Arlington VA Marsha Mitchum, MS, MPHҰ ‡ The George Washington University School of Public Health, Washington, D.C. Neal Sikka, MD* Ұ The George Washington University School of Medicine, Washington, D.C. Marianne Carim, MDҰ € Georgetown University School of Nursing and Health Studies Michael A. Stoto, PhD€ Supervising Section Editor: Scott E. Rudkin, MD, MBA Submission history: Submitted August 28, 2009; Revision Received July 22, 2009; Accepted July 22, 2009 Reprints available through open access at http://escholarship.org/uc/uciem_westjem Background: The purpose of syndromic surveillance is early detection of a disease outbreak. Such systems rely on the earliest data, usually chief complaint. The growing use of electronic medical records (EMR) raises the possibility that other data, such as emergency department (ED) diagnosis, may provide more specific information without significant delay, and might be more effective in detecting outbreaks if mechanisms are in place to monitor and report these data. -

Module 10: Vital Signs

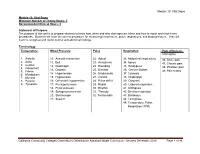

Module 10: Vital Signs Module 10: Vital Signs Minimum Number of Theory Hours: 3 Recommended Clinical Hours: 6 Statement of Purpose: The purpose of this unit is to prepare students to know how, when and why vital signs are taken and how to report and chart these procedures. Students will learn the correct procedure for measuring temperature, pulse, respirations, and blood pressure. They will learn to recognize and report normal and abnormal findings. Terminology: Temperature: Blood Pressure Pulse Respiration Pain (effects on Vital signs) 1. Afebrile 10. Aneroid manometer 22. Apical 33. Abdominal respirations 46. Acute pain 2. Axilla 11. Bell 23. Arrhythmia 34. Apnea 47. Chronic pain 3. Celsius 12. Diaphragm 24. Bounding 35. Bradypnea 4. Fahrenheit 48. Phantom pain 13. Diastolic 25. Brachial 36. Cheyne-Stokes 5. Febrile 49. Pain scales 6. Metabolism 14. Hypertension 26. Bradycardia 37. Cyanosis 7. Mucosa 15. Hypotension 27. Carotid 38. Diaphragm 8. Pyrexia 16. Orthostatic hypotension 28. Pulse deficit 39. Dyspnea 9. Tympanic 17. Pre-hypertension 29. Radial 40. Labored respiration 18. Pulse pressure 30. Rhythm 41. Orthopnea 19. Sphygmomanometer 31. Thready 42. Shallow respiration 20. Stethoscope 32. Tachycardia 43. Stertorous 21. Systolic 44. Tachypnea 45. Temperature, Pulse, Respiration (TPR) Patient, patient/resident, and client are synonymous terms Californiareferring to Community the person Colleges Chancellor’s Office Nurse Assistant Model Curriculum - Revised December 2018 Page 1 of 46 receiving care Module 10: Vital Signs Patient, resident, and client are synonymous terms referring to the person receiving care Performance Standards (Objectives): Upon completion of three (3) hours of class plus homework assignments and six (6) hours of clinical experience, the student will be able to: 1. -

Mod. 3 Vital Signs

Mod. 3 Vital Signs 1. What is most important to assess during secondary assessment? a. Airway b. Pulse c. Respiration d. Chief complaint 2. The first set of vital sign measurements obtained are often referred to as which of the following? a. Baseline vital signs b. Normal vital signs c. Standard vital signs d. None of the above 3. A patient with a pulse rate of 120 beats per minute is considered which of the following? a. Dyscardic b. Normocardic c. Tachycardic d. Bradycardic 4. Where do baseline vital signs fit into the sequence of patient assessment? a. Ongoing assessment b. At primary assessment c. At secondary assessment d. At the patient's side 5. In a conscious adult patient, which of the following pulses should be assessed initially? a. Brachial b. Radial c. Carotid d. Pedal 6. You are assessing a 55-year-old male complaining of chest pain and have determined that his radial pulse is barely palpable. You also determine that there were 20 pulsations over a span of 30 seconds. Based on this, how would you report this patient's pulse? a. Pulse 20, weak, and regular b. Pulse 20 and weak c. Pulse 40 and weak d. Pulse 40, weak, and irregular 7. Which of the following are the vital signs that need to be recorded? a. Pulse, respiration, skin color, skin temperature and condition b. Pulse, respiration, skin color, skin temperature and condition, pupils, blood pressure, and bowel sounds c. Pulse, respiration, skin color, skin temperature and condition, pupils, and blood pressure d. Pulse, respiration, skin color, skin temperature, pupils, and blood pressure 8. -

Chief Compaint/HPI History

PULMONOLOGY ASSOCIATES OF TEXAS 6860 North Dallas Pkwy, Ste 200, Plano, TX 75024 Tel: 469-305-7171 Fax: 469-212-1548 Patient Name: Thomas Cromwell Patient DOB: 02-09-1960 Patient Sex: Male Visit Date: 03-06-2016 Chief Compaint/HPI Chief Complaint: Shortness of Breath History of Present Illness: he patient is an 56-year-old male. From the last few days, he is not feeling well. Complains of fatigue, tiredness, weakness, nausea, no vomiting, no hematemesis or melena. The patient relates to have some low-grade fever. The patient came to the emergency room. Initially showed atrial fibrillation with rapid ventricular response. It appears that the patient has chronic atrial fibrillation. As per the medications, they are not very clear. He denies any specific chest pain. Her main complaint is shortness of breath and symptoms as above Pulmonary symptoms: cough, sputum, no hemoptysis, dyspnea and wheezing. History Past Medical History: Pulmonary history includes pneumonia and sleep apnea. Cardiac history includes atrial fibrillation and congestive heart failure. Remainder of PMH is non-significant. Surgical History: appendectomy in 2007. Medications: Pulmonary medications are albuterol and Spiriva; Cardiac medications include: atenolol and digoxin; Family History: Father is deceased at age 80. Father PMH remarkable for CHF, hypertension and MI; Mother is alive. Mother PMH remarkable for alzheimers, diabetes and hypertension; Cancer history in family: No Lung disease in the family: No Social History: Current every day smoker - 1 pack / day Alcohol consumption: social Marital status: lives alone Exposure History: Occupation: farmer. Asbestos exposure: None. No exposure to Ground Zero. Immunization History: Patient has an immunization history of flu shot, H1N1shot and pneumococcal shot. -

Medical Terminology Information Sheet

Medical Terminology Information Sheet: Medical Chart Organization: • Demographics and insurance • Flow sheets • Physician Orders Medical History Terms: • Visit notes • CC Chief Complaint of Patient • Laboratory results • HPI History of Present Illness • Radiology results • ROS Review of Systems • Consultant notes • PMHx Past Medical History • Other communications • PSHx Past Surgical History • SHx & FHx Social & Family History Types of Patient Encounter Notes: • Medications and medication allergies • History and Physical • NKDA = no known drug allergies o PE Physical Exam o Lab Laboratory Studies Physical Examination Terms: o Radiology • PE= Physical Exam y x-rays • (+) = present y CT and MRI scans • (-) = Ф = negative or absent y ultrasounds • nl = normal o Assessment- Dx (diagnosis) or • wnl = within normal limits DDx (differential diagnosis) if diagnosis is unclear o R/O = rule out (if diagnosis is Laboratory Terminology: unclear) • CBC = complete blood count o Plan- Further tests, • Chem 7 (or Chem 8, 14, 20) = consultations, treatment, chemistry panels of 7,8,14,or 20 recommendations chemistry tests • The “SOAP” Note • BMP = basic Metabolic Panel o S = Subjective (what the • CMP = complete Metabolic Panel patient tells you) • LFTs = liver function tests o O = Objective (info from PE, • ABG = arterial blood gas labs, radiology) • UA = urine analysis o A = Assessment (Dx and DDx) • HbA1C= diabetes blood test o P = Plan (treatment, further tests, etc.) • Discharge Summary o Narrative in format o Summarizes the events of a hospital stay -

History & Physical Format

History & Physical Format SUBJECTIVE (History) Identification name, address, tel.#, DOB, informant, referring provider CC (chief complaint) list of symptoms & duration. reason for seeking care HPI (history of present illness) - PQRST Provocative/palliative - precipitating/relieving Quality/quantity - character Region - location/radiation Severity - constant/intermittent Timing - onset/frequency/duration PMH (past medical /surgical history) general health, weight loss, hepatitis, rheumatic fever, mono, flu, arthritis, Ca, gout, asthma/COPD, pneumonia, thyroid dx, blood dyscrasias, ASCVD, HTN, UTIs, DM, seizures, operations, injuries, PUD/GERD, hospitalizations, psych hx Allergies Meds (Rx & OTC) SH (social history) birthplace, residence, education, occupation, marital status, ETOH, smoking, drugs, etc., sexual activity - MEN, WOMEN or BOTH CAGE Review Ever Feel Need to CUT DOWN Ever Felt ANNOYED by criticism of drinking Ever Had GUILTY Feelings Ever Taken Morning EYE OPENER FH (family history) age & cause of death of relatives' family diseases (CAD, CA, DM, psych) SUBJECTIVE (Review of Systems) skin, hair, nails - lesions, rashes, pruritis, changes in moles; change in distribution; lymph nodes - enlargement, pain bones , joints muscles - fractures, pain, stiffness, weakness, atrophy blood - anemia, bruising head - H/A, trauma, vertigo, syncope, seizures, memory eyes- visual loss, diplopia, trauma, inflammation glasses ears - deafness, tinnitis, discharge, pain nose - discharge, obstruction, epistaxis mouth - sores, gingival bleeding, teeth, -

NASA 10-Minute Lean Test* Instructions

NASA 10-minute Lean Test* instructions: Orthostatic intolerance (OI) is an umbrella term used to describe the development of symptoms while in upright posture that are relieved by reclining. Orthostatic hypotension (OH), neurally mediated hypotension (NMH) [or neurogenic orthostatic hypotension/NOH] and postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (PoTS) are terms used to describe variants of this response. The 2015 IOM/NAM clinical diagnostic criteria for ME/CFS establish that orthostatic intolerance is a common and often overlooked feature of illness that is objectively measurable. OI may contribute to dizziness, fatigue, headache, cognitive dysfunction, chest (palpitations, shortness of breath) or abdominal discomfort (nausea), tremor or anxiety and various pain manifestations. We recommend that all ME/CFS and FMS patients undergo a NASA 10- minute Lean Test to assess for orthostatic intolerance. A baseline test will be most revealing if measures that reduce orthostatic intolerance are withheld before testing. For example: limit extra fluid and sodium intake, do not wear compression socks, and alter the intake of medications that might influence the test (see examples below). These treatments can be resumed after the test. Tools needed: Blood Pressure cuff and finger pulsoximeter. Two observers—one to obtain BP values and one to scribe and instruct. Ask the patient to remove shoes and socks and lie down comfortably on a bed or exam table in quiet supine position for 15-20 minutes to reach circulatory equilibrium1. After the 15-20 minutes, record the patient’s blood pressure (BP) and heart rate (HR). Repeat a minute later. If repeat vital signs are not similar, retake until two consecutive readings are relatively consistent.