Reassessing the Development Experiences of Gujarat and Kerala’, Dissertation for Msc in Contemporary India, Oxford University, June

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Creating Sustainable Surat* Climate Change Plan Surat Agenda Topics of Discussion

Surat Municipal Corporation The Southern Gujarat Chamber of Commerce & Namaste ! Industry *Creating sustainable Surat* Climate Change Plan Surat Agenda Topics of Discussion About Surat Results to-date ~ Climate Hazards ~ Apparent Areas of Climate Vulnerability and Likely Future Issues Activities and Methods ~ Work Plan ~ Organizations Involved ~ CAC Arrangement ~ Activities undertaken so far ~ Methods Used for Analysis Sectoral Studies Pilot Projects Challenges and Questions Next Steps Glory of Surat Historical Centre for Trade & Commerce English, Dutch, Armenian & Moguls Settled Leading City of Gujarat 9th Largest City of India Home to Textile and Diamond Industries 60% of Nation’s Man Made Fabric Production 600,000 Power Looms and 450 Process Houses Traditional Zari and Zardosi Work 70% of World’s Diamond Cutting and Polishing Spin-offs from Hazira, Largest Industrial Hub Peace-loving, Resilient and Harmonious Environment Growth of Surat Year 1951 Area 1961 Sq. in Km 1971 8.18 223,182 Population 1981 8.18 288,026 1991 33.85 471,656 2001 55.56 776,583 2001* 111.16 1,498,817 2009 112.27 2,433,785 326.51 2,877,241 Decline of Emergence of 326.51 ~ Trade Centre Development mercantile of Zari, silk & Diamond, Chief port of of British India – Continues to trade – regional other small Textiles & Mughal Empire trade centre other mfg. 4 be major port and medium million industries Medieval Times 1760- late 1800s 1900 to 1950s 1950s to 1980s 1980s onwards Emergence of Petrochemicals -Re-emergence Consolidation as major port, of -

Proposal for a Gujarati Script Root Zone Label Generation Ruleset (LGR)

Proposal for a Gujarati Root Zone LGR Neo-Brahmi Generation Panel Proposal for a Gujarati Script Root Zone Label Generation Ruleset (LGR) LGR Version: 3.0 Date: 2019-03-06 Document version: 3.6 Authors: Neo-Brahmi Generation Panel [NBGP] 1 General Information/ Overview/ Abstract The purpose of this document is to give an overview of the proposed Gujarati LGR in the XML format and the rationale behind the design decisions taken. It includes a discussion of relevant features of the script, the communities or languages using it, the process and methodology used and information on the contributors. The formal specification of the LGR can be found in the accompanying XML document: proposal-gujarati-lgr-06mar19-en.xml Labels for testing can be found in the accompanying text document: gujarati-test-labels-06mar19-en.txt 2 Script for which the LGR is proposed ISO 15924 Code: Gujr ISO 15924 Key N°: 320 ISO 15924 English Name: Gujarati Latin transliteration of native script name: gujarâtî Native name of the script: ગજુ રાતી Maximal Starting Repertoire (MSR) version: MSR-4 1 Proposal for a Gujarati Root Zone LGR Neo-Brahmi Generation Panel 3 Background on the Script and the Principal Languages Using it1 Gujarati (ગજુ રાતી) [also sometimes written as Gujerati, Gujarathi, Guzratee, Guujaratee, Gujrathi, and Gujerathi2] is an Indo-Aryan language native to the Indian state of Gujarat. It is part of the greater Indo-European language family. It is so named because Gujarati is the language of the Gujjars. Gujarati's origins can be traced back to Old Gujarati (circa 1100– 1500 AD). -

District Fact Sheet Junagadh Gujarat

Ministry of Health and Family Welfare National Family Health Survey - 4 2015 -16 District Fact Sheet Junagadh Gujarat International Institute for Population Sciences (Deemed University) Mumbai 1 Introduction The National Family Health Survey 2015-16 (NFHS-4), the fourth in the NFHS series, provides information on population, health and nutrition for India and each State / Union territory. NFHS-4, for the first time, provides district-level estimates for many important indicators. The contents of previous rounds of NFHS are generally retained and additional components are added from one round to another. In this round, information on malaria prevention, migration in the context of HIV, abortion, violence during pregnancy etc. have been added. The scope of clinical, anthropometric, and biochemical testing (CAB) or Biomarker component has been expanded to include measurement of blood pressure and blood glucose levels. NFHS-4 sample has been designed to provide district and higher level estimates of various indicators covered in the survey. However, estimates of indicators of sexual behaviour, husband’s background and woman’s work, HIV/AIDS knowledge, attitudes and behaviour, and, domestic violence will be available at State and national level only. As in the earlier rounds, the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India designated International Institute for Population Sciences, Mumbai as the nodal agency to conduct NFHS-4. The main objective of each successive round of the NFHS has been to provide essential data on health and family welfare and emerging issues in this area. NFHS-4 data will be useful in setting benchmarks and examining the progress in health sector the country has made over time. -

Surat: As a Major Port-Town of Gujarat and Its Trade History

IOSR Journal Of Humanities And Social Science (IOSR-JHSS) Volume 19, Issue 5, Ver. VI (May. 2014), PP 69-73 e-ISSN: 2279-0837, p-ISSN: 2279-0845. www.iosrjournals.org Surat: As a Major Port-Town of Gujarat and its Trade History Sagufta Parveen Research Scholar, Aligarh Muslim University Aligarh (India) Abstract: A port is a place, where people, goods and culture are transferred between land and maritime space. It is a mingle point of ocean and inland transport. A harbor is the essential transit point for the volume of the trade, permitting the imports of goods, which were not in a sufficient amount and the export of items which the country has an excess or has a competitive edge to produce contributing to the progress of its economy. The effectiveness of a port is important in international trade since a seaport is the nerve of foreign trade of a country. Surat is an ancient city and port by all evidence and had been through centuries a centre of maritime trade. The city was very populous and full of merchants. The city had a very considerable number of foreign settlers. Apart from the Europeans, there were Turks, Jews, Arabians, Persians and Armenians. Surat was a great port and commercial centre. The 17th century was an era of the prosperity for the city of Surat. The two great sources that contributed to the wealth and prosperity of the city were foreign commerce and domestic manufactures. Surat was a commercial emporium, besides such commodities as indigo, spices and cloths, many important goods imported from Europe were sold in its markets. -

The Political Historiography of Modern Gujarat

The Political Historiography of Modern Gujarat Tannen Neil Lincoln ISBN 978-81-7791-236-4 © 2016, Copyright Reserved The Institute for Social and Economic Change, Bangalore Institute for Social and Economic Change (ISEC) is engaged in interdisciplinary research in analytical and applied areas of the social sciences, encompassing diverse aspects of development. ISEC works with central, state and local governments as well as international agencies by undertaking systematic studies of resource potential, identifying factors influencing growth and examining measures for reducing poverty. The thrust areas of research include state and local economic policies, issues relating to sociological and demographic transition, environmental issues and fiscal, administrative and political decentralization and governance. It pursues fruitful contacts with other institutions and scholars devoted to social science research through collaborative research programmes, seminars, etc. The Working Paper Series provides an opportunity for ISEC faculty, visiting fellows and PhD scholars to discuss their ideas and research work before publication and to get feedback from their peer group. Papers selected for publication in the series present empirical analyses and generally deal with wider issues of public policy at a sectoral, regional or national level. These working papers undergo review but typically do not present final research results, and constitute works in progress. Working Paper Series Editor: Marchang Reimeingam THE POLITICAL HISTORIOGRAPHY OF MODERN -

FACTORS AFFECTING PROFICIENCY AMONG GUJARATI HERITAGE LANGUAGE LEARNERS on THREE CONTINENTS a Dissertation Submitted to the Facu

FACTORS AFFECTING PROFICIENCY AMONG GUJARATI HERITAGE LANGUAGE LEARNERS ON THREE CONTINENTS A Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of Georgetown University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Linguistics By Sheena Shah, M.S. Washington, DC May 14, 2013 Copyright 2013 by Sheena Shah All Rights Reserved ii FACTORS AFFECTING PROFICIENCY AMONG GUJARATI HERITAGE LANGUAGE LEARNERS ON THREE CONTINENTS Sheena Shah, M.S. Thesis Advisors: Alison Mackey, Ph.D. Natalie Schilling, Ph.D. ABSTRACT This dissertation examines the causes behind the differences in proficiency in the North Indian language Gujarati among heritage learners of Gujarati in three diaspora locations. In particular, I focus on whether there is a relationship between heritage language ability and ethnic and cultural identity. Previous studies have reported divergent findings. Some have found a positive relationship (e.g., Cho, 2000; Kang & Kim, 2011; Phinney, Romero, Nava, & Huang, 2001; Soto, 2002), whereas others found no correlation (e.g., C. L. Brown, 2009; Jo, 2001; Smolicz, 1992), or identified only a partial relationship (e.g., Mah, 2005). Only a few studies have addressed this question by studying one community in different transnational locations (see, for example, Canagarajah, 2008, 2012a, 2012b). The current study addresses this matter by examining data from members of the same ethnic group in similar educational settings in three multi-ethnic and multilingual cities. The results of this study are based on a survey consisting of questionnaires, semi-structured interviews, and proficiency tests with 135 participants. Participants are Gujarati heritage language learners from the U.K., Singapore, and South Africa, who are either current students or recent graduates of a Gujarati School. -

Socio-Political Condition of Gujarat Daring the Fifteenth Century

Socio-Political Condition of Gujarat Daring the Fifteenth Century Thesis submitted for the dc^ee fif DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN HISTORY By AJAZ BANG Under the supervision of PROF. IQTIDAR ALAM KHAN Department of History Aligarh Muslim University, Aligarb- 1983 T388S 3 0 JAH 1392 ?'0A/ CHE':l!r,D-2002 CENTRE OF ADVANCED STUDY TELEPHONE SS46 DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY ALIGARH-202002 TO WHOM IT MAY CONCERN This is to certify that the thesis entitled 'Soci•-Political Condition Ml VB Wtmmimt of Gujarat / during the fifteenth Century' is an original research work carried out by Aijaz Bano under my Supervision, I permit its submission for the award of the Degree of the Doctor of Philosophy.. /-'/'-ji^'-^- (Proi . Jrqiaao;r: Al«fAXamn Khan) tc ?;- . '^^•^\ Contents Chapters Page No. I Introduction 1-13 II The Population of Gujarat Dxiring the Sixteenth Century 14 - 22 III Gujarat's External Trade 1407-1572 23 - 46 IV The Trading Cotnmxinities and their Role in the Sultanate of Gujarat 47 - 75 V The Zamindars in the Sultanate of Gujarat, 1407-1572 76 - 91 VI Composition of the Nobility Under the Sultans of Gujarat 92 - 111 VII Institutional Featvires of the Gujarati Nobility 112 - 134 VIII Conclusion 135 - 140 IX Appendix 141 - 225 X Bibliography 226 - 238 The abljreviations used in the foot notes are f ollov.'ing;- Ain Ain-i-Akbarl JiFiG Arabic History of Gujarat ARIE Annual Reports of Indian Epigraphy SIAPS Epiqraphia Indica •r'g-acic and Persian Supplement EIM Epigraphia Indo i^oslemica FS Futuh-^ffi^Salatin lESHR The Indian Economy and Social History Review JRAS Journal of Asiatic Society ot Bengal MA Mi'rat-i-Ahmadi MS Mirat~i-Sikandari hlRG Merchants and Rulers in Giijarat MF Microfilm. -

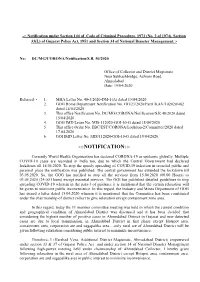

Notification Under Section 144 of Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973 (No

-:: Notification under Section 144 of Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973 (No. 2 of 1974), Section 33(L) of Gujarat Police Act, 1951 and Section 34 of National Disaster Management::- No: DC/MG/CORONA/Notification/S.R. 50/2020 Office of Collector and District Magistrate Near Subhashbridge, Ashram Road, Ahmedabad Date: 19/04/2020 Referred: - 1. MHA Letter No. 40-3/2020-DM-1(A) dated 15/04/2020 2. GOG Home Department Notification No. GG/23/2020/Part1/KAV/102020/482 dated 14/04/2020 3. This office Notification No. DC/MG/CORONA/Notification/S.R.48/2020 dated 15/04/2020 4. GOG IMD Letter No. MIS-112020-GOI-10-G dated 15/04/2020 5. This office Order No. EBC/EST/CORONA/Lockdon-2/Committee/2020 dated 17.04.2020 6. GOI IMD Letter No. MIS/112020-GOI-10-G dated 19/04/2020. -::NOTIFICATION::- Currently World Health Organization has declared CORONA-19 as epidemic globally. Multiple COVID-10 cases are recorded in India too, due to which the Central Government had declared lockdown till 14.04.2020. To stop the speedy spreading of COVID-19 infection in crowded public and personal place the notification was published. The central government has extended the lockdown till 03.05.2020. So, the GOG has notified to stop all the services from 15.04.2020 (00.00 Hours) to 03.05.2020 (24:00 Hours) except essential services. The GOI has published detailed guidelines to stop spreading COVID-19 wherein in the para-3 of guidance it is mentioned that the certain relaxation will be given to minimize public inconvenience. -

F. Vegetable Crops Sr

JUNAGADH AGRICULTURAL UNIVERSITY, JUNAGADH F. Vegetable crops Sr. No. Variety/ Hybrid 14. Tomato 14.1 Junagadh Tomato 3 (JT 3) 14.2 Gujarat Tomato 6 (GT 6) 15. Brinjal 15.1 Junagadh Brinjal Green Round 1 (JBGR 1) 15.2 Gujarat Junagadh Brinjal 2 (GJB 2) 15.3 Gujarat Junagadh Brinjal 3 (GJB 3) 15.4 Gujarat Junagadh Long Brinjal 4* (GJLB 4) 15.5 Gujarat Junagadh Brinjal Hybrid 4 (GJBH 4) 15.6 Gujarat Round Brinjal 5 (GRB 5) 16. Okra 16.1 Gujarat Okra 3* (GO 3) 16.2 Gujarat Okra Hybrid 2* (GOH 2) 16.3 Gujarat Junagadh Okra 3 (GJO 3) 16.4 Gujarat Junagadh Okra Hybrid 3* (GJOH 3) 16.5 Gujarat Junagadh Okra Hybrid 4* (GJOH 4) 16.6 Gujarat Okra 6 (GO 6) 17. Garlic 17.1 Gujarat Garlic 4* (GG 4) 17.2 Gujarat Junagadh Garlic 5 (GJG 5) 18. Onion 18.1 Gujarat Junagadh Red Onion 11 (GJRO 11) 18.2 Gujarat Junagadh White Onion 3 (GJWO 3) 19. Sponge Gourd 19.1 Gujarat Sponge Gourd 1* (GSG 1) 19.2 Gujarat Junagadh Sponge Gourd 2 (GJSG 2) 20. Ridge Gourd 20.1 Gujarat Junagadh Ridge Gourd Hybrid 1(GJRGH 1) 21. Indian Bean 21.1 Gujarat Junagadh Indian Bean 11 (GJIB 11) 21.2 Gujarat Junagadh Indian Bean 2 (GJIB 2) * Released at state and national level. 14. Tomato 14.1 Junagadh Tomato 3 (JT 3) 1 Name of crop Tomato 2 Botanical name Lycopercicum esculentum L. 3 Name of variety Junagadh Tomato 3 (JT 3) 4 Parentage with details of its The genotype was selection from the local collection pedigree made from surrounding area of Kuwadava village of Rajkot district. -

Syllabus BBA BCA Sem-4 EC202 History of Gujarat and Its Culture

Elective Course EC-202(5) HISTORY OF GUJARAT AND ITS CULTURE Course Introduction: The course would make students know about the history of ancient Gujarat and its magnificent heritage. It also discusses about the people who have contributed in respective fields and have increased the glory of Gujarat. The course will give the student a feel of having pilgrimage around Gujarat. Objectives: The student would be able to: 1) To get familiar with various sculptures and monuments of Gujarat. 2) Brief knowledge of different Rulers periods like maurya, maitrak as well as some well known folks. 3) To learn about varieties in culture and life style of people in Gujarat. No. of Credits: 2 Theory Sessions per week: 2 Teaching Hours: 20 hours UNIT TOPICS / SUBTOPICS 1 Gujarat’s Geography • The Historicity of Ancient Gujarat: o The brief history of Gujarat, Lothal, Dholavira, Dwarka and Somnath o Maurya period and Gujarat Chandragupt maurya, About Girinagar, Bindu Sarovar, Ashok, Vikramaditya. o Shak - kshatraps period and Gujarat Sudarshan talav o Gupta period and Gujarat o Maitrak period and Gujarat (Valabhipur) o Gurjar – Pratihar period and Gujarat (Post-Maitrak period) o Chavda period and Gujarat Jayshikhari, Vanraj, Yogaraj, Samantsinh and Mularaj. o Solanki period and Gujarat The invasion of Gaznavi on somnath, Bhimdev, Karandeo, Minaldevi, Siddharaj,kumarpal, Bhimdev-second. o Vaghela period and Guajrat o Pragvats and naagars, Vastupal, Tejpal, Karanghelo, Vishaldev 2 The Glittering Lamps, Geography of Gujarat • Gujarat’s Geography : Location, Latitude, Longitude, Rivers, Mountains, Environment. • The Glittering Lamps Mahatma Gandhiji, Narsinh Mehta, Meera, Premanand,Narmad, Zaverchand Meghani, Tana Riri, Baiju Bawara, Avinash Vyas, Praful Dave, Ravishankar Raval, Homai Vyarawala, Mrinalini Sarabhai, Kumudini Lakhia, Dr. -

Surat: the First Steps of the French Adventure in India

8 SURAT: THE FIRST STEPS OF THE FRENCH ADVENTURE IN INDIA Sara Keller | résidente à l’IEA de Nantes Historienne et archéologue du bâti formée en France et en Allemagne, les recherches de Sara Keller portent sur les monuments et les structures urbaines historiques comme source d’information pour l’étude de contextes socio-culturels pluriels. Spécialiste de l’architecture médiévale et moderne de l’Inde du Nord, elle travaille notamment sur les villes portuaires du Gujarat et les transferts culturels et technologiques entre l’Orient et l’Occident, dont ces cités sont le théâtre depuis plusieurs millénaires. The French “comptoir” in the in Surat in 1668. The French India. Rather than questioning remains from the glorious age of the factory into a Consulate, great Mughal port of Surat representative of the CFIO soon the economic and politic mea- of Surat are visible today, and and following the seizure of (1668-1778) tells the story of sensed the limits of their econo- ning of the French Factory in the architectural elements the Consulate by the British the first enterprising steps of mic perspectives in Surat as late Surat, my study aims to recons- of the French establishment authorities. In these regards, the French colonial adventure. comers in an extremely complex truct the reality of the French in Surat were not spared by the archival documents of the Surat, one of the greatest port socio-economic system. Their presence in the port town. What this modernizing urge. This consulate (1773-8) conserved towns of both Indian Ocean and efforts pushed them towards are the topographical and archi- infrastructural silence brings at the “Archives Diplomatiques Indian History, presents a com- other local and extra- regional tectural traces of this presence in fuzziness around the meaning de Nantes” represent an plex and fascinating socio- poli- littorals, to the benefit of other and around Surat? A pluridisci- of the French presence in extraordinary source of data tical picture which is repeatedly factories and settlements (with plinary study based on historical Surat. -

Gujarat English

GUJARAT A JOURNEY THROUGH INDIA Embroidered umbrella in the Tarnetar Fair in Gujarat Written and Illustrated by ABHISHEIKH Gujarat by Abhisheikh Illustrations © Abhisheikh Text © Pratham Books, 2008 First English Edition: 2008 Illustrations: Abhisheikh ISBN: 978-81-8479-032-0 Registered Office: PRATHAM BOOKS 633-634, 4th “C” Main, 6th ‘B’ Cross, OMBR Layout, Banaswadi, Bangalore 560 043 ✆ 080-25429726 / 27 / 28 Regional Offices: Mumbai ✆ 022-65162526 New Delhi ✆ 011-65684113 Typesetting and Layout by: Pratham Books, Delhi Printed by: Jasmine Art Printers Pvt. Ltd., Mumbai Published by: Pratham Books www.prathambooks.org All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or distributed in any form or by any means, or stored in a database or retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the publisher. Gujarat is a border state of India. It is also known as Gujjar Rashtra. Gujjars are a migrant tribe which came to India in the 5th century and settled here. GUJARAT Written and Illustrated by Abhisheikh A boy wearing a regional costume. Gujarati is the language spoken in Gujarat and these are Gujarati alphabets. A girl wearing a traditional dress. Folk art and craft from Gujarat is very colorful. Embroidery and tie and dye are done mainly is Saurashtra and Kutch. In the villages, you can find beautiful clay craft. Exotic clay relief and mirror inlay work are commonly found in homes all over rural Gujarat. Gujarat had many royal kingdoms. Palaces like Kusumvillas and Baroda Palace tell stories of its royal past. Kathputlis (wooden puppets) are an important form of entertainment in rural fairs and festivals of Gujarat.