Vol 68 1&2.Pdf (4.087Mb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

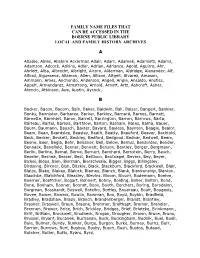

Family Name Files That Can Be Accessed in the Boerne Public Library Local and Family History Archives

FAMILY NAME FILES THAT CAN BE ACCESSED IN THE BOERNE PUBLIC LIBRARY LOCAL AND FAMILY HISTORY ARCHIVES A Abadie, Ables, Abshire Ackerman Adair, Adam, Adamek, Adamietz, Adams, Adamson, Adcock, Adkins, Adler, Adrian, Adriance, Agold, Aguirre, Ahr, Ahrlett, Alba, Albrecht, Albright, Alcorn, Alderman, Aldridge, Alexander, Alf, Alford, Algueseva, Allamon, Allen, Allison, Altgelt, Alvarez, Amason, Ammann, Ames, Anchondo, Anderson, Angell, Angle, Ansaldo, Anstiss, Appelt, Armendarez, Armstrong, Arnold, Arnott, Artz, Ashcroft, Asher, Atencio, Atkinson, Aue, Austin, Aycock, B Backer, Bacon, Bacorn, Bain, Baker, Baldwin, Ball, Balser, Bangert, Bankier, Banks, Bannister, Barbaree, Barker, Barkley, Barnard, Barnes, Barnett, Barnette, Barnhart, Baron, Barrett, Barrington, Barron, Barrows, Barta, Barteau, Bartel, Bartels, Barthlow, Barton, Basham, Bates, Batha, Bauer, Baum, Baumann, Bausch, Baxter, Bayard, Bayless, Baynton, Beagle, Bealor, Beam, Bean, Beardslee, Beasley, Beath, Beatty, Beauford, Beaver, Bechtold, Beck, Becker, Beckett, Beckley, Bedford, Bedgood, Bednar, Bedwell, Beem, Beene, Beer, Begia, Behr, Beissner, Bell, Below, Bemus, Benavides, Bender, Bennack, Benefield, Benner, Bennett, Benson, Bentley, Berger, Bergmann, Berlin, Berline, Bernal, Berne, Bernert, Bernhard, Bernstein, Berry, Besch, Beseler, Beshea, Besser, Best, Bettison, Beutnagel, Bevers, Bey, Beyer, Bickel, Bidus, Bien, Bierman, Bierschwale, Bigger, Biggs, Billingsley, Birdsong, Birkner, Bish, Bitzkie, Black, Blackburn, Blackford, Blackwell, Blair, Blaize, Blake, Blakey, Blalock, -

Safavid Figural Silks and the Display of Identity

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings Textile Society of America 2008 Donning the Cloak: Safavid Figural Silks and the Display of Identity Nazanin Hedayat Shenasa De Anza College, [email protected] Nazanin Hedayat Munroe Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf Part of the Art and Design Commons Shenasa, Nazanin Hedayat and Munroe, Nazanin Hedayat, "Donning the Cloak: Safavid Figural Silks and the Display of Identity" (2008). Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings. 133. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf/133 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Textile Society of America at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Donning the Cloak: Safavid Figural Silks and the Display of Identity Nazanin Hedayat Shenasa [email protected] Introduction In a red world bathed in shimmering gold light, a man sits with his head in his hand as wild beasts encircle him. He is emaciated, has unkempt hair, and wears only a waistcloth—but he has a dreamy smile on his face. Nearby, a camel bears a palanquin carrying a stately woman, her head tipped to one side, arm outstretched from the window of her traveling abode toward her lover. Beneath her, the signature “Work of Ghiyath” is woven in Kufic script inside an eight- 1 pointed star on the palanquin (Fig. 1). Figure 1. Silk lampas fragment depicting Layla and Majnun. -

Participant List

Participant List 10/20/2019 8:45:44 AM Category First Name Last Name Position Organization Nationality CSO Jillian Abballe UN Advocacy Officer and Anglican Communion United States Head of Office Ramil Abbasov Chariman of the Managing Spektr Socio-Economic Azerbaijan Board Researches and Development Public Union Babak Abbaszadeh President and Chief Toronto Centre for Global Canada Executive Officer Leadership in Financial Supervision Amr Abdallah Director, Gulf Programs Educaiton for Employment - United States EFE HAGAR ABDELRAHM African affairs & SDGs Unit Maat for Peace, Development Egypt AN Manager and Human Rights Abukar Abdi CEO Juba Foundation Kenya Nabil Abdo MENA Senior Policy Oxfam International Lebanon Advisor Mala Abdulaziz Executive director Swift Relief Foundation Nigeria Maryati Abdullah Director/National Publish What You Pay Indonesia Coordinator Indonesia Yussuf Abdullahi Regional Team Lead Pact Kenya Abdulahi Abdulraheem Executive Director Initiative for Sound Education Nigeria Relationship & Health Muttaqa Abdulra'uf Research Fellow International Trade Union Nigeria Confederation (ITUC) Kehinde Abdulsalam Interfaith Minister Strength in Diversity Nigeria Development Centre, Nigeria Kassim Abdulsalam Zonal Coordinator/Field Strength in Diversity Nigeria Executive Development Centre, Nigeria and Farmers Advocacy and Support Initiative in Nig Shahlo Abdunabizoda Director Jahon Tajikistan Shontaye Abegaz Executive Director International Insitute for Human United States Security Subhashini Abeysinghe Research Director Verite -

Muslims in Spain, 1492–1814 Mediterranean Reconfigurations Intercultural Trade, Commercial Litigation, and Legal Pluralism

Muslims in Spain, 1492– 1814 Mediterranean Reconfigurations Intercultural Trade, Commercial Litigation, and Legal Pluralism Series Editors Wolfgang Kaiser (Université Paris I, Panthéon- Sorbonne) Guillaume Calafat (Université Paris I, Panthéon- Sorbonne) volume 3 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/ cmed Muslims in Spain, 1492– 1814 Living and Negotiating in the Land of the Infidel By Eloy Martín Corrales Translated by Consuelo López- Morillas LEIDEN | BOSTON This is an open access title distributed under the terms of the CC BY-NC 4.0 license, which permits any non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited. Further information and the complete license text can be found at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ The terms of the CC license apply only to the original material. The use of material from other sources (indicated by a reference) such as diagrams, illustrations, photos and text samples may require further permission from the respective copyright holder. Cover illustration: “El embajador de Marruecos” (Catalog Number: G002789) Museo del Prado. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Martín Corrales, E. (Eloy), author. | Lopez-Morillas, Consuelo, translator. Title: Muslims in Spain, 1492-1814 : living and negotiating in the land of the infidel / by Eloy Martín-Corrales ; translated by Consuelo López-Morillas. Description: Leiden ; Boston : Brill, [2021] | Series: Mediterranean reconfigurations ; volume 3 | Original title unknown. | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2020046144 (print) | LCCN 2020046145 (ebook) | ISBN 9789004381476 (hardback) | ISBN 9789004443761 (ebook) Subjects: LCSH: Muslims—Spain—History. | Spain—Ethnic relations—History. -

The Substrates for British Colonization to Enter Iran in the Safavid Era Dr

International Journal of Scientific & Engineering Research Volume 3, Issue 6, June-2012 1 ISSN 2229-5518 The Substrates for British Colonization to Enter Iran in the Safavid Era Dr. Masoud Moradi, Reza Vasegh Abbasi, Amir Shiranzaie Ghale-No Abstract— Since the beginning of the sixteenth century AD and after the fall of Constantinople, the context was provided for dominating the countries like Spain, Portugal, France and England on seas and travelling to eastern countries. This domination coincided with the reign of the Tudors in England. One hundred and fifty years after Klavikhou and the rise of Antony English Jenkinson which was thought for making a trading relationship with Iran, many attempts have been made from the European communities to communicate with the Orient, including Iran which their incentive was first to make the movements of tourists easier and Christian missionaries and then to make the commercial routes more secure. Antony Jenkins was among the first who traveled to Iran in 1561 to establish commercial relations and then went to King Tahmasb. Thomas Alkak, Arthur Edwards and Shirley Brothers was among those who continued his way after him which Shirley Brothers was the most successful of them. This study aims to study, in a laboratory method, the beginning of Iran’s relation with England in the era of Tahmasb the first and its continuity in the era of King Abbas The First and how English colonization to enter Iran are established. Index Terms— Iran, England, Safavid, British tradesmen, commercial relations. —————————— —————————— 1 INTRODUCTION NTONY Jenkinson, the Initiator of British Activities sending the mission to Iran represented by Jenkins: first A in Iran: After the collapse of the Byzantine State to take aside the silk trade from the Portuguese being the (1453), European initiated their activities to reach most important commercial trade of Iran and then take Asia, especially the thriving market of India and exploit- over the exports by itself. -

Surnames in Bureau of Catholic Indian

RAYNOR MEMORIAL LIBRARIES Montana (MT): Boxes 13-19 (4,928 entries from 11 of 11 schools) New Mexico (NM): Boxes 19-22 (1,603 entries from 6 of 8 schools) North Dakota (ND): Boxes 22-23 (521 entries from 4 of 4 schools) Oklahoma (OK): Boxes 23-26 (3,061 entries from 19 of 20 schools) Oregon (OR): Box 26 (90 entries from 2 of - schools) South Dakota (SD): Boxes 26-29 (2,917 entries from Bureau of Catholic Indian Missions Records 4 of 4 schools) Series 2-1 School Records Washington (WA): Boxes 30-31 (1,251 entries from 5 of - schools) SURNAME MASTER INDEX Wisconsin (WI): Boxes 31-37 (2,365 entries from 8 Over 25,000 surname entries from the BCIM series 2-1 school of 8 schools) attendance records in 15 states, 1890s-1970s Wyoming (WY): Boxes 37-38 (361 entries from 1 of Last updated April 1, 2015 1 school) INTRODUCTION|A|B|C|D|E|F|G|H|I|J|K|L|M|N|O|P|Q|R|S|T|U| Tribes/ Ethnic Groups V|W|X|Y|Z Library of Congress subject headings supplemented by terms from Ethnologue (an online global language database) plus “Unidentified” and “Non-Native.” INTRODUCTION This alphabetized list of surnames includes all Achomawi (5 entries); used for = Pitt River; related spelling vartiations, the tribes/ethnicities noted, the states broad term also used = California where the schools were located, and box numbers of the Acoma (16 entries); related broad term also used = original records. Each entry provides a distinct surname Pueblo variation with one associated tribe/ethnicity, state, and box Apache (464 entries) number, which is repeated as needed for surname Arapaho (281 entries); used for = Arapahoe combinations with multiple spelling variations, ethnic Arikara (18 entries) associations and/or box numbers. -

Universi^ Micn^Lms

INFORMATION TO USERS This reproduction was made from a copy of a document sent to us for microfilming. While the most advanced technology has been used to photograph and reproduce this document, the quality of the reproduction is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help clarify markings or notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or “target” for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is “Missing Page(s)”. If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting througli an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a round black mark, it is an indication of either blurred copy because of movement during exposure, duplicate copy, or copyrighted materials that should not have been filmed. For blurred pages, a good image of the page can be found in the adjacent frame. If copyrighted materials were deleted, a target note will appear listing the pages in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., is part of the material being photographed, a definite method of “sectioning” the material has been followed. It is customary to begin filming at the upper left hand comer of a large sheet and to continue from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. If necessary, sectioning is continued again—beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. -

Exploration, Disruption, Diaspora: Movement of Nuevomexicanos to Utah, 1776-1850 Linda C

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository American Studies ETDs Electronic Theses and Dissertations Spring 5-11-2019 Exploration, Disruption, Diaspora: Movement of Nuevomexicanos to Utah, 1776-1850 Linda C. Eleshuk Roybal Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/amst_etds Part of the American Studies Commons Recommended Citation Eleshuk Roybal, Linda C.. "Exploration, Disruption, Diaspora: Movement of Nuevomexicanos to Utah, 1776-1850." (2019). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/amst_etds/80 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Electronic Theses and Dissertations at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in American Studies ETDs by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Linda Catherine Eleshuk Roybal Candidate American Studies Department This dissertation is approved and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication: Approved by the Dissertation Committee: A.Gabriel Meléndez, Chair Kathleen Holscher Michelle Hall Kells Enrique Lamadrid i Exploration, Disruption, Diaspora: Movement Of Nuevomexicanos to Utah, 1776 – 1950 By Linda Catherine Eleshuk Roybal B.S. Psychology, Weber State College, 1973 B.S. Communications, Weber State University, 1982 M.S. English, Utah State University, 1997 DISSERTATION Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy In American Studies The University of New Mexico Albuquerque, New Mexico May 2019 ii Dedication This dissertation is dedicated to my children and grandchildren, born and yet to be — Joys of my life and ambassadors to a future I will not see, Con mucho cariño. iii Acknowledgements I am grateful to so many people who have shared their expertise and resources to bring this project to its completion. -

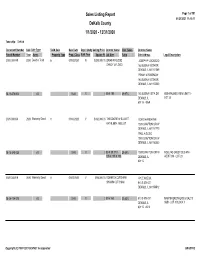

Ao-Sales-Dekalb2020.Pdf

Sales Listing Report Page 1 of 191 01/21/2021 11:10:11 DeKalb County 1/1/2020 - 12/31/2020 Township: DeKalb Document Number Sale Sale Type Valid Sale Sale Date Dept. Study Selling Price Grantor Name Curr. Sales Grantee Name Parcel Number Year Acres Property Type Prop. Class Built Year Square Ft. Lot Size Ratio Site Address Legal Description 2020-000145 2020 Deed in Trust N 01/03/2020 N $325,000.00 BRIAN R FLOOD JOSEPH P LOCASCIO SANDY L FLOOD 163 BUENA VISTA DR DEKALB, IL 601151069 PENNY A ROSENOW 163 BUENA VISTA DR DEKALB, IL 601150000 08-11-478-006 .00 0040 0 0 90 X 180 29.97% 163 BUENA VISTA DR KISHWAUKEE VIEW UNIT 3 - DEKALB, IL LOT 23 60115 -1069 2020-000166 2020 Warranty Deed Y 01/03/2020 Y $182,000.00 THEODORE W ELLIOTT ELVI S HANDAYANI KATHLEEN J ELLIOT 1509 CRAYTON CIR W DEKALB, IL 601151770 PAUL A GOGO 1509 CRAYTON CIR W DEKALB, IL 601150000 08-15-248-028 .00 0040 0 0 80 X 39.27 X 29.69% 1509 CRAYTON CIR W ROLLING CREST SUB 4TH 105 X 105 X 130 DEKALB, IL ADDITION - LOT 28 60115 2020-000219 2020 Warranty Deed Y 01/07/2020 Y $94,000.00 ROBERTA CUTSHAW KYLE KOZIOL SHAWN CUTSHAW 913 S 5TH ST DEKALB, IL 601154512 08-26-104-010 .00 0040 0 0 50 x 169 33.62% 913 S 5TH ST MARTIN BROTHERS & GALTS DEKALB, IL SUB - LOT 3 BLOCK 1 60115 -4512 Copyright (C) 1997-2021 DEVNET Incorporated BRADTKE Sales Listing Report Page 2 of 191 01/21/2021 11:10:11 DeKalb County 1/1/2020 - 12/31/2020 Township: DeKalb Document Number Sale Sale Type Valid Sale Sale Date Dept. -

PETITION List 04-30-13 Columns

PETITION TO FREE LYNNE STEWART: SAVE HER LIFE – RELEASE HER NOW! • 1 Signatories as of 04/30/13 Arian A., Brooklyn, New York Ilana Abramovitch, Brooklyn, New York Clare A., Redondo Beach, California Alexis Abrams, Los Angeles, California K. A., Mexico Danielle Abrams, Ann Arbor, Michigan Kassim S. A., Malaysia Danielle Abrams, Brooklyn, New York N. A., Philadelphia, Pennsylvania Geoffrey Abrams, New York, New York Tristan A., Fort Mill, South Carolina Nicholas Abramson, Shady, New York Cory a'Ghobhainn, Los Angeles, California Elizabeth Abrantes, Cambridge, Canada Tajwar Aamir, Lawrenceville, New Jersey Alberto P. Abreus, Cliffside Park, New Jersey Rashid Abass, Malabar, Port Elizabeth, South Salma Abu Ayyash, Boston, Massachusetts Africa Cheryle Abul-Husn, Crown Point, Indiana Jamshed Abbas, Vancouver, Canada Fadia Abulhajj, Minneapolis, Minnesota Mansoor Abbas, Southington, Connecticut Janne Abullarade, Seattle, Washington Andrew Abbey, Pleasanton, California Maher Abunamous, North Bergen, New Jersey Andrea Abbott, Oceanport, New Jersey Meredith Aby, Minneapolis, Minnesota Laura Abbott, Woodstock, New York Alexander Ace, New York, New York Asad Abdallah, Houston, Texas Leela Acharya, Toronto, Canada Samiha Abdeldjebar, Corsham, United Kingdom Dennis Acker, Los Angeles, California Mohammad Abdelhadi, North Bergen, New Jersey Judith Ackerman, New York, New York Abdifatah Abdi, Minneapolis, Minnesota Marilyn Ackerman, Brooklyn, New York Hamdiya Fatimah Abdul-Aleem, Charlotte, North Eddie Acosta, Silver Spring, Maryland Carolina Maria Acosta, -

Pre-Orientalism in Costume and Textiles — ISSN 1229-3350(Print) ISSN 2288-1867(Online) — J

Journal of Fashion Business Vol.22, No.6 Pre-Orientalism in Costume and Textiles — ISSN 1229-3350(Print) ISSN 2288-1867(Online) — J. fash. bus. Vol. 22, No. 6:39-52, December. 2018 Keum Hee Lee† https://doi.org/ 10.12940/jfb.2018.22.6.39 Dept. of Fashion Design & Marketing, Seoul Women’s University, Korea Corresponding author — Keum Hee Lee Tel : +82-2-970-5627 Fax : +82-2-970-5979 E-mail: [email protected] Keywords Abstract Pre-Orientalism, Orientalism, The objective of this study was to enhance understanding and appreciation of oriental fashion, Pre-Orientalism in costumes and textiles by revealing examples of Oriental cultural-exchange, influences in Europe from the 16th century to the mid-18th century through in-depth study. The research method used were the presentation and analysis of previous literature research and visual data. The result were as follows; Pre-Orientalism had been influenced by Morocco, Thailand, and Persia as well as Turkey, India, and China. In this study, Pre-Orientalism refers to oriental influence and oriental taste in Western Europe through cultural exchanges from the 16th century to the mid-18th century. The oriental costume was the most popular subspecies of fancy, luxury dress and was a way to show off wealth and intelligence. Textiles were used for decoration and luxury. The Embassy and the court in Versailles and Vienna led to a frenzy of oriental fashion. It appeared that European in the royal family and aristocracy of Europe had been accommodated without an accurate understanding of the Orient. Although in this study, the characteristics, factors, and impacts of Pre-Orientalism have not — been clarified, further study can be done. -

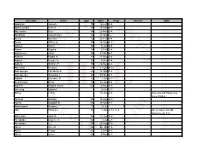

Surname Given Age Date Page Maiden Note Abdullah Joseph 70 5-Feb A-8 Abercrombie Bert H

Surname Given Age Date Page Maiden Note Abdullah Joseph 70 5-Feb A-8 Abercrombie Bert H. 88 29-Dec B-9 Abernathy Kate 84 22-Nov B-4 Abraham Joseph Ben 86 21-Mar D-2 Acela Michael 73 23-Feb A-4 Achor Arthur A. 58 16-Sep A-11 Adalay Steve 92 6-Jan B-6 Adam Sophia 78 3-Feb B-4 Adamczyk John 85 21-Oct B-7 Adams Edwin B. 81 27-Aug B-4 Adank Cassie R. 75 7-Dec A-4 Adank William F. 76 24-Dec A-8 Adelman Irving D. 59 31-Oct D-10 Adelsperger Elizabeth A. 60 18-Mar A-8 Adelsperger Susanna T. 82 25-Oct A-7 Adoba Michael, Sr. 80 1-Jun A-12 Aeschliman Betty 32 18-Jan B-4 Aguirre Regina Avilla 63 4-Nov A-6 Ahlering Edward 6-Oct C-7 Ahley Lillian 15-Jun A-6 Also spelled Haley see June 16 E-2 Ahmed Hassan 68 13-Aug A-9 Akers Edward W. 66 16-Mar A-7 Aksentijevic Rodney 15 8-Jul 1 Alb Florence 70 1-Jun A-12, C-5 Gives name as Alb Florence on C-5 Albertson Jack R. 59 11-Jun C-2 Alexander Eugene A. 62 7-Jul C-8 Alexander L.C. 58 20-Aug B-3 Allen Cleo D. 66 26-Jan A-6 Allen Frosty 65 2-Dec B-6 Allen Grace 65 9-Nov B-3 Allen James Virgil 55 19-Aug A-4 Allen Weber 62 2-Mar A-4 Alley George Wesley 54 4-Jan A-5 Alonzo Maria 73 15-Oct B-5 Altshuller Nathan D.