Atlanta Symphony Orchestra

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Victor Stanislavsky Is Hailed As One of the Most Outstanding Young Israeli Pianists Today

Victor Stanislavsky is hailed as one of the most outstanding young Israeli pianists today. His international career has taken him to many countries in Europe, north and south America, China, South Korea and Australia. In the past concert season, he has given over 70 performances as a soloist, recitalist and a chamber musician to critical acclaim. As an avid chamber musician he has collaborated with such artists as violinists Christian Tetzlaff and David Garrett, cellist Gary Hoffman and Soprano Chen Reis. His major festival appearances include “Ravinia” (Chicago), “Meet in Beijing”, “Shanghai piano Festival” and the “Israel Festival”. Mr. Stanislavsky has performed in prestigious venues including Carnegie Hall and the 92Y in New-York, Chicago Arts Center, Bass performance hall in Fort Worth, Berlin Philharmonie, the Concertgebouw in Amsterdam, St. Martin in the Fields Church in London, “Tsarytsino” Palace in Moscow, National Performing Arts Center in Beijing, Forbidden City concert hall in Beijing, Shanghai Conservatory, Qintai Grand Theater in Wuhan, Harbin Opera House and the Seoul Arts Center to name a few. In addition he regularly performs in all the major concert halls in Israel. He performed as a soloist with Milan’s Symphony Orchestra, China’s National Symphony Orchestra, China’s national Ballet Symphony Orchestra, KBS Symphony orchestra of South Korea and others as well as with leading orchestras in Israel collaborating with such conductors as Yoel Levi, Jose Maria Florencio, Kainen Johns, Li Xincao, Uri Segal, Gil Shohat and many others. Mr. Stanislavsky holds both bachelors and masters degrees summa cum laude, in music performance from the Buchmann-Mehta School of Music at Tel-Aviv University, where he studied with Mr. -

Msm Women's Chorus

MSM WOMEN’S CHORUS Kent Tritle, Ronnie Oliver, Jr., Hannah Nacheman, and Alejandro Zuleta, Conductors Vanessa May-lok Lee, piano Francesca Leo, flute Liana Hoffman and Shengmu Wang, horn Minyoung Kwon and Frances Konomi, harp Tamika Gorski (MM ’17), marimba Elliot Roman and Alexandros Darna, percussion WEDNESDAY, FEBRUARY 27, 2019 | 7:30 PM NEIDORFF-KARPATI HALL WEDNESDAY, FEBRUARY 27, 2019 | 7:30 PM NEIDORFF-KARPATI HALL MSM WOMEN’S CHORUS Kent Tritle, Ronnie Oliver, Jr., Hannah Nacheman, and Alejandro Zuleta, Conductors Vanessa May-lok Lee, piano Francesca Leo, flute Liana Hoffman and Shengmu Wang, horn Minyoung Kwon and Frances Konomi, harp Tamika Gorski (MM ’17), marimba Elliot Roman and Alexandros Darna, percussion PROGRAM STEPHEN PAULUS The Earth Sings (1949–2014) I. Day Break II. Sea and Sky III. Wind and Sun Alejandro Zuleta, Conductor Vanessa May-lok Lee, piano Elliot Roman and Alexandros Darna, percussion GUSTAV HOLST Choral Hymns from the Rig Veda, Group 3, H. 99, (1874–1934) Op. 26 Hymn to the Dawn Hymn to the Waters Hymn to Vena (Sun rising through the mist) Hymn of the Travellers Hannah Nacheman, Conductor Minyoung Kwon, harp VINCENT Winter Cantata, Op. 97 PERSICHETTI I. A Copper Pheasant (1915–1987) II. Winter’s First Drizzle III. Winter Seclusion I V. The Woodcutter V. Gentlest Fall of Snow VI. One Umbrella VII. Of Crimson Ice VIII. The Branch Is Black IX. Fallen Leaves X. So Deep XI. The Wind’s Whetstone XII. Epilogue Ronnie Oliver, Jr., Conductor Francesca Leo, flute Tamika Gorski (MM ’17), marimba JOHANNES BRAHMS Vier Gesänge (Four Songs), Op. -

Music at the Supreme Court

~~~1-J-u .§nv<tmt t!!onri of 14• ~a .Siatt• ~R ~i"-'-'-- ._rutlfington. ~. <If. 2ll.;t'l~ ~ d " ~ JUSTIC;:"HARRY A . BLACKMU ~ April 6, 1994 - ------ /cr/1;¢~ MEMORANDUM TO THE CONFERENC~ I advised both the President and the Chief Justice some months ago that this would be my last Term in active service on the Court. I now am writing the President formally that I shall assume retirement status pursuant to 28 U.S.C. §371(b), as of the date the Court "rises" for the summer or as of the date of the qualification of my successor, whichever is later, but, in any event, not subsequent to September 25, 1994. It has been a special experience to be on the Federal Bench for over 34 years and on this Court for 24 Terms. I am grateful for the opportunity to have worked with each of you and with nine of your predecessors. I shall miss the Court, its work, and its relationships. But I leave it in good hands. Sincerely, ~ ~ tf,4i. cc: Chief Justice Burger Justice Brennan Justice White Justice Powell April 6, 1994 Dear Harry: The news of your retirement plans came as a surprise. You appear to be in good health, and certainly you have been carrying more than your share of the caseload. You will rank in history as one of the truly great Justices. I have been proud to have you as a friend. I know that Jo would join me in sending affectionate best wishes to you and Dottie. As ever, Justice Blackmun lfpjss be: Mrs. -

Alumni Recital

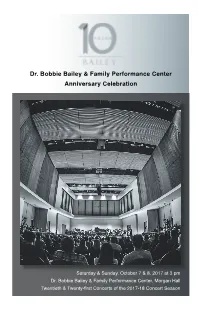

Dr. Bobbie Bailey & Family Performance Center Anniversary Celebration Saturday & Sunday, October 7 & 8, 2017 at 3 pm Dr. Bobbie Bailey & Family Performance Center, Morgan Hall Twentieth & Twenty-first Concerts of the 2017-18 Concert Season alumni recital Saturday, October 7, 2017 FELIX MENDELSSOHN (1809–1847) Rondo capriccioso in E Major, Op. 14 Huu Mai, piano CAMILLE SAINT-SAËNS (1835–1921) Fantasie for Violin and Harp, Op. 124 Ryan Gregory, violin Tyler Hartley, harp HALSEY STEVENS (1908–1989) Sonata for Trumpet and Piano Mvt. I Justin Rowan, trumpet Judy Cole, piano J. S. BACH (1685–1750) Concerto for Two Violins Mvt. I & II Grace Kawamura, violin Jonathan Urizar, violin Huu Mai, piano GIOACHINO ROSSINI (1792–1868) la calunia from il barbiere di Siviglia Eric Lindsey, bass Judy Cole, piano GIUSEPPE VERDI (1813–1901) Caro nome from Rigoletto Amy Smithwick. soprano Judy Cole, piano CÉSAR FRANCK (1822–1890) Violin Sonata in A minor Mvt. IV Grace Kawamura, violin Huu Mai, piano ANDREW LIPPA (b. 1964) What is it about her? from Wild Party Nick Morrett, tenor Judy Cole, piano MICHAEL OPTIZ (b. 1995) Two Weeks Brian Reid, piano Janna Graham, vibraphone Brandon Radaker, bass Robert Boone, drums Michael Opitz, tenor saxophone Luke Weathington, alto saxophone Michael DeSousa, trombone BRANDON BOONE (b. 1994) Last Minute Brian Reid, piano Janna Graham, vibraphone Brandon Radaker, bass Robert Boone, drums JANNA GRAHAM (b. 1992) Nayem, I Am Brian Reid, piano Janna Graham, vibraphone Brandon Radaker, bass Robert Boone, drums Michael Opitz, tenor saxophone Luke Weathington, alto saxophone Michael DeSousa, trombone FRÉDÉRIC CHOPIN (1810–1849) Ballade No. -

Press Kit About the Nashville Symphony

Nashville Symphony 2019/2020 Press Kit About the Nashville Symphony ed by music director Giancarlo Guerrero, the Nashville Symphony has been professional orchestra careers. Currently, 20 participating students receive individual Lan integral part of the Music City sound since 1946. The 83-member ensemble instrument instruction, performance opportunities, and guidance on applying to performs more than 150 concerts annually, with a focus on contemporary American colleges and conservatories, all offered free of charge. orchestral music through collaborations with composers including Jennifer Higdon, Terry Riley, Joan Tower and Aaron Jay Kernis. The orchestra is equally renowned for Schermerhorn Symphony Center, the orchestra’s home since 2006, is considered one of its commissioning and recording projects with Nashville-based artists including bassist the world’s finest acoustical venues. Named in honor of former music director Kenneth Edgar Meyer, banjoist Béla Fleck, singer-songwriter Ben Folds and electric bassist Victor Schermerhorn and located in the heart of downtown Nashville, the building boasts Wooten. distinctive neo-Classical architecture incorporating motifs and design elements that pay homage to the history, culture and people of Middle Tennessee. Within its intimate An established leader in Nashville’s arts and cultural community, the Symphony has design, the 1,800-seat Laura Turner Hall contains several unique features, including facilitated several community collaborations and initiatives, most notably Violins soundproof windows, the 3,500-pipe Martin Foundation Concert Organ, and an of Hope Nashville, which spotlighted a historic collection of instruments played by innovative mechanical system that transforms the hall from theater-style seating to a Jewish musicians during the Holocaust. -

Website Bio Goldstein

Alon Goldstein Artistic Director and featured performer at the Abby Bach Festival 2019 Alon Goldstein is one of the most original and sensitive pianists of his generation, admired for his musical intelligence, dynamic personality, artistic vision and innovative programming. He has played with the Philadelphia orchestra, the Chicago Symphony, the San Francisco, Baltimore, St. Louis, Dallas, Houston, Toronto and Vancouver symphonies, as well as the Israel Philharmonic, London Philharmonic, Los Angeles and Radio France Orchestra. He played under the baton of such conductors as Zubin Mehta, Herbert Blomstedt, Vladimir Jurowski, Rafael Frübeck de Burgos, Peter Oundjian, Yoel Levi, Yoav Talmi, Leon Fleisher and others. His 2018-19 season includes appearances with the Kansas City, Ann Arbor, Illinois, Spokane, Bangor, Augusta, and Pensacola Symphony Orchestras, as well as a performance of Beethoven’s Emperor Concerto on fortepiano with Mercury Houston. He will play in Mexico with the Xalapa Symphony Bernstein’s "Age of Anxiety” to celebrate the composer’s centennial, and perform the New Year’s concert with the Beijing symphony in China. He will also perform recitals and chamber music, including tours with the Goldstein-Peled-Fiterstein Trio, the Tempest Trio, and the Fine Arts Quartet at the Mendelssohn International festival in Hamburg Germany, as well as in Cleveland, Washington D.C., New York, Burlington, Key West, Sarasota, Melbourne, Duluth, and other cities. This season will also include a CD release of Mozart Piano Concerti Nos. 23 and 24 with the Fine Arts Quartet (a follow-up to their critically acclaimed recording of Nos. 20 and 21) and Scarlatti Piano Sonatas on the Naxos label. -

Jean Berger (1909–2002): a Biographical Chronology

AMERICAN MUSIC RESEARCH CENTER JOURNAL Volume 18 2010 Thomas L. Riis, Editor-in-Chief American Music Research Center College of Music University of Colorado at Boulder THE AMERICAN MUSIC RESEARCH CENTER Thomas L. Riis, Director Laurie J. Sampsel, Curator Eric J. Harbeson, Archivist Sister Mary Dominic Ray, O.P. (1913–1994), Founder Karl Kroeger, Archivist Emeritus William Kearns, Senior Fellow Daniel Sher, Dean, College of Music William S. Farley, Research Assistant, 2009 –2010 K. Dawn Grapes, Research Assistant, 2009–2011 EDITORIAL BOARD C. F. Alan Cass Kip Lornell Susan Cook Portia Maultsby Robert R. Fink Tom C. Owens William Kearns Katherine Preston Karl Kroeger Jessica Sternfeld Paul Laird Joanne Swenson-Eldridge Victoria Lindsay Levine Graham Wood The American Music Research Center Journal is published annually. Subscription rate is $25.00 per issue ($28.00 outside the U.S. and Canada). Please address all inquiries to Lisa Bailey, American Music Research Center, 288 UCB, University of Colorado, Boulder, CO 80309-0288. E-mail: [email protected] The American Music Research Center website address is www.amrccolorado.org ISSN 1058-3572 © 2010 by the Board of Regents of the University of Colorado INFORMATION FOR AUTHORS The American Music Research Center Journal is dedicated to publishing articles of general interest about American music, particularly in subject areas relevant to its collections. We welcome submission of articles and pro - posals from the scholarly community, ranging from 3,000 to 10,000 words (excluding notes). All articles should be addressed to Thomas L. Riis, College of Music, University of Colorado at Boulder, 301 UCB, Boulder, CO 80309-0301. -

Acclaimed Israeli-American Pianist Daniel Gortler in Recital at the Jewish Museum May 24

Acclaimed Israeli-American Pianist Daniel Gortler in Recital at the Jewish Museum May 24 Theme and Variations Features Works by Corigliano, Mendelssohn, Beethoven, and Schumann New York, NY, April 23, 2018 – The Jewish Museum will present Israeli-American pianist Daniel Gortler performing Theme and Variations, a concert honoring American composer John Corigliano’s 80th birthday, on Thursday, May 24 at 7:30pm. This is Mr. Gortler’s fourth recital at the Jewish Museum. The concert program, which explores the idea of “variations on a theme,” features Corigliano’s Fantasia on an Ostinato together with Mendelssohn’s Variations sérieuses, Op. 54, Beethoven’s Piano Sonata No. 30 in E major, Op. 109, and Schumann’s epic Symphonic Etudes, Op.13 along with the five posthumous variations. Tickets for the May 24 concert are $24 general; $18 students and seniors; and $14 Jewish Museum members. Further program and ticket information is available online at TheJewishMuseum.org/calendar or by calling 212.423.3337. The Jewish Museum is located at Fifth Avenue and 92nd Street, Manhattan. The recital program will include: Felix Mendelssohn (1809-1847) Variations sérieuses, Op. 54 Published 1841 Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827) Piano Sonata No. 30 in E major, Op. 109 Published 1820 Vivace ma non troppo - Adagio espressivo Prestissimo Gesangvoll, mit innigster Empfindung. Andante molto cantabile ed espressivo John Corigliano (b. 1938) Fantasia on an Ostinato Published 1985 Intermission Robert Schumann (1810-1856) Theme and Variations, Symphonic Etudes Op. 13 (with the 5 Posthumous Variations ) Published 1837/1852 Felix Mendelssohn: Variations sérieuses, Op. 54 This is Mendelssohn's most-often performed substantial piano work. -

Zubin Cancels U.S. Tour Participation Due to Health Reasons -- Press Release

From: American Friends of the Israel Philharmonic Orchestra Contact: Rubenstein Communications Adam Miller [email protected], 212-843-8032 Kelsey Stokes [email protected], 212-843-9317 ______________________________________________________________________________ Draft for Release MAESTRO ZUBIN MEHTA CANCELS HIS PARTICIPATION IN ISRAEL PHILHARMONIC ORCHESTRA’S UPCOMING 2019 U.S. TOUR DUE TO HEALTH REASONS Yoel Levi to Replace Mehta on Six-City Tour New York, NY, Jan, XX. 2019 – The American Friends of the Israel Philharmonic Orchestra today announced that Maestro Zubin Mehta has been forced to bow out of the Israel Philharmonic Orchestra’s upcoming 2019 U.S. Tour (Feb. 2-9) due to health reasons. Filling in for Mehta on the six-city tour is Yoel Levi, one of the world’s leading conductors, known for his vast repertoire, masterly interpretations and electrifying performances. The IPO’s 2019 U.S. Tour was to mark Maestro Mehta’s final U.S. tour before he retires as Music Director of the IPO in 2019, leaving behind a legacy of exceptional musicianship and humanitarianism. “The unexpected news of Zubin’s cancellation is an unfortunate turn of events, but we are grateful to Yoel for stepping in to conduct what we know will be a very exciting and uplifting U.S. Tour for the IPO,” said David Hirsch, President of the Board of the American Friends of the Israel Philharmonic Orchestra. Hirsch continued, “We had been looking forward to celebrating and honoring Zubin’s immeasurable contributions to the Israel Philharmonic, during what would have been his final U.S. tour as Music Director. All concerts on this tour conducted by Yoel will still be performed in recognition of Zubin.” Levi has had a long-standing relationship with the IPO, notably as the first Israeli to serve as Principal Guest Conductor of the Israel Philharmonic. -

2001 Distinguished Artist

DaleWarland 2001 Distinguished Artist the mc knight foundation Introduction horal music is perhaps the most ubiquitous American art form, performed in and out of tune by school and church choirs in every city, town, and rural outpost. But choral music in the Dale Warland style—elegant, moving, provocative, sublime— is rare. Few professional choruses exist in the United States today; even fewer exhibit the quality of the Dale Warland Singers. Warland’s decision to establish his career in Minnesota has brought countless rewards to musicians and audiences here. As a collaborator with local music organizations, a commissioner of Minnesota composers, a conductor of Ceagerly anticipated concerts, and a recording artist, Warland has made Minnesota a national center of choral music. In so doing, he has kept an ancient tradition alive and relevant. Be sure to hear for yourself on the commemorative CD recording inside the back cover of this book. To achieve so much, an artist must have high expectations of himself and others. There is no doubt that Warland is demanding, but always in a way that is warm, human, and inspiring—that makes people want to do their best. Person after person who has been associated with Warland mentions his modesty, his quiet nature, his thoughtfulness, and his support. He leads by example. The McKnight Foundation created the Distinguished Artist Award to honor those whose lasting presence has made Minnesota a more creative, more culturally alive place. Dale Warland has conducted his Singers and others all over the world. He is internationally recognized as one of the masters of choral music. -

Choral Ensembles

Department of Music If you enjoyed tonight’s concert, we invite you to attend the inaugural concert of the presents Kennesaw State University Community Alumni Choir Saturday, November 10, 2007 8:00 pm • Bailey Performance Center Concert Hall Kennesaw State University Choral Ensembles Dr. Leslie J. Blackwell, conductor Sherri Barrett, accompanist Sam Skelton, soprano saxophone Jana Young, soprano Tuesday, October 16, 2007 8:00 pm Dr. Bobbie Bailey and Family Performance Center Concert Hall Tenth concert of the 2007-2008 season Kennesaw State University Kennesaw State University Choral Ensembles Upcoming Music Events Dr. Leslie J. Blackwell, conductor Sherri Barrett, accompanist Wednesday, October 17 Kennesaw State University October 16, 2007 Orchestra 8:00 pm 8:00 pm • Bailey Performance Center Concert Hall Dr. Bobbie Bailey and Family Performance Center Concert Hall Sunday, October 21 Kennesaw State University PROGRAM Faculty Chamber Players 7:30 pm • Bailey Performance Center Concert Hall Kennesaw State University Chorale Tuesday, October 30 Hosanna in excelsis Brent Pierce Kennesaw State University Male Chorus Day Hosanna in excelsis……………………Hosanna in the highest 7:30 pm • Bailey Performance Center Concert Hall Oh My Luve’s Like A Red, Red Rose Rene Clausen Sunday, November 4 For I Went with the Multitude George Frideric Handel Cobb Symphony Orchestra Georgia Youth Symphony Philharmonia I Know I’ve Been Changed arr. Damon H. Dandridge 4:00 pm • Bailey Performance Center Concert Hall Steven Hickerson and Stephanie Slaughter, soloists Sunday, November 4 Cobb Symphony Orchestra Georgia Youth Symphony Orchestra 7:00 pm • Bailey Performance Center Concert Hall Kennesaw State University Chamber Singers Plorate filli Israel from Jephthah Giacomo Carissimi Thursday, November 8 Kennesaw State University Plorate filii Israel, Orchestra and Chamber Singers plorate omnes virgins et filiam Jephte unigenitam 8:00 pm • Bailey Performance Center Concert Hall in carmine doloris, doloris lamentamini. -

Stephen Paulus: the Road Home (2002) History and Comparative Analysis to Its Parent Piece Prospect (1833)

CLARKE UNIVERSITY STEPHEN PAULUS: THE ROAD HOME (2002) HISTORY AND COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS TO ITS PARENT PIECE PROSPECT (1833) BY ADAM DAVID O'DELL Capstone: Music MUSC 499-1 Dubuque, IA 2014 A document submitted to the music faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts in Music © Adam D. O'Dell 2014 All Rights Reserved Table of Contents I. Introduction..........................................................................................................................1 II. Background..........................................................................................................................3 1. Stephen Paulus...............................................................................................................3 2. Sacred Harp Singing.......................................................................................................5 A. History......................................................................................................................5 B. Theory and Composition..........................................................................................8 C. Texts........................................................................................................................1 3 D. Decline....................................................................................................................13 III. Analysis..............................................................................................................................14