Stephen Paulus: the Road Home (2002) History and Comparative Analysis to Its Parent Piece Prospect (1833)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Msm Women's Chorus

MSM WOMEN’S CHORUS Kent Tritle, Ronnie Oliver, Jr., Hannah Nacheman, and Alejandro Zuleta, Conductors Vanessa May-lok Lee, piano Francesca Leo, flute Liana Hoffman and Shengmu Wang, horn Minyoung Kwon and Frances Konomi, harp Tamika Gorski (MM ’17), marimba Elliot Roman and Alexandros Darna, percussion WEDNESDAY, FEBRUARY 27, 2019 | 7:30 PM NEIDORFF-KARPATI HALL WEDNESDAY, FEBRUARY 27, 2019 | 7:30 PM NEIDORFF-KARPATI HALL MSM WOMEN’S CHORUS Kent Tritle, Ronnie Oliver, Jr., Hannah Nacheman, and Alejandro Zuleta, Conductors Vanessa May-lok Lee, piano Francesca Leo, flute Liana Hoffman and Shengmu Wang, horn Minyoung Kwon and Frances Konomi, harp Tamika Gorski (MM ’17), marimba Elliot Roman and Alexandros Darna, percussion PROGRAM STEPHEN PAULUS The Earth Sings (1949–2014) I. Day Break II. Sea and Sky III. Wind and Sun Alejandro Zuleta, Conductor Vanessa May-lok Lee, piano Elliot Roman and Alexandros Darna, percussion GUSTAV HOLST Choral Hymns from the Rig Veda, Group 3, H. 99, (1874–1934) Op. 26 Hymn to the Dawn Hymn to the Waters Hymn to Vena (Sun rising through the mist) Hymn of the Travellers Hannah Nacheman, Conductor Minyoung Kwon, harp VINCENT Winter Cantata, Op. 97 PERSICHETTI I. A Copper Pheasant (1915–1987) II. Winter’s First Drizzle III. Winter Seclusion I V. The Woodcutter V. Gentlest Fall of Snow VI. One Umbrella VII. Of Crimson Ice VIII. The Branch Is Black IX. Fallen Leaves X. So Deep XI. The Wind’s Whetstone XII. Epilogue Ronnie Oliver, Jr., Conductor Francesca Leo, flute Tamika Gorski (MM ’17), marimba JOHANNES BRAHMS Vier Gesänge (Four Songs), Op. -

Music at the Supreme Court

~~~1-J-u .§nv<tmt t!!onri of 14• ~a .Siatt• ~R ~i"-'-'-- ._rutlfington. ~. <If. 2ll.;t'l~ ~ d " ~ JUSTIC;:"HARRY A . BLACKMU ~ April 6, 1994 - ------ /cr/1;¢~ MEMORANDUM TO THE CONFERENC~ I advised both the President and the Chief Justice some months ago that this would be my last Term in active service on the Court. I now am writing the President formally that I shall assume retirement status pursuant to 28 U.S.C. §371(b), as of the date the Court "rises" for the summer or as of the date of the qualification of my successor, whichever is later, but, in any event, not subsequent to September 25, 1994. It has been a special experience to be on the Federal Bench for over 34 years and on this Court for 24 Terms. I am grateful for the opportunity to have worked with each of you and with nine of your predecessors. I shall miss the Court, its work, and its relationships. But I leave it in good hands. Sincerely, ~ ~ tf,4i. cc: Chief Justice Burger Justice Brennan Justice White Justice Powell April 6, 1994 Dear Harry: The news of your retirement plans came as a surprise. You appear to be in good health, and certainly you have been carrying more than your share of the caseload. You will rank in history as one of the truly great Justices. I have been proud to have you as a friend. I know that Jo would join me in sending affectionate best wishes to you and Dottie. As ever, Justice Blackmun lfpjss be: Mrs. -

Press Kit About the Nashville Symphony

Nashville Symphony 2019/2020 Press Kit About the Nashville Symphony ed by music director Giancarlo Guerrero, the Nashville Symphony has been professional orchestra careers. Currently, 20 participating students receive individual Lan integral part of the Music City sound since 1946. The 83-member ensemble instrument instruction, performance opportunities, and guidance on applying to performs more than 150 concerts annually, with a focus on contemporary American colleges and conservatories, all offered free of charge. orchestral music through collaborations with composers including Jennifer Higdon, Terry Riley, Joan Tower and Aaron Jay Kernis. The orchestra is equally renowned for Schermerhorn Symphony Center, the orchestra’s home since 2006, is considered one of its commissioning and recording projects with Nashville-based artists including bassist the world’s finest acoustical venues. Named in honor of former music director Kenneth Edgar Meyer, banjoist Béla Fleck, singer-songwriter Ben Folds and electric bassist Victor Schermerhorn and located in the heart of downtown Nashville, the building boasts Wooten. distinctive neo-Classical architecture incorporating motifs and design elements that pay homage to the history, culture and people of Middle Tennessee. Within its intimate An established leader in Nashville’s arts and cultural community, the Symphony has design, the 1,800-seat Laura Turner Hall contains several unique features, including facilitated several community collaborations and initiatives, most notably Violins soundproof windows, the 3,500-pipe Martin Foundation Concert Organ, and an of Hope Nashville, which spotlighted a historic collection of instruments played by innovative mechanical system that transforms the hall from theater-style seating to a Jewish musicians during the Holocaust. -

2001 Distinguished Artist

DaleWarland 2001 Distinguished Artist the mc knight foundation Introduction horal music is perhaps the most ubiquitous American art form, performed in and out of tune by school and church choirs in every city, town, and rural outpost. But choral music in the Dale Warland style—elegant, moving, provocative, sublime— is rare. Few professional choruses exist in the United States today; even fewer exhibit the quality of the Dale Warland Singers. Warland’s decision to establish his career in Minnesota has brought countless rewards to musicians and audiences here. As a collaborator with local music organizations, a commissioner of Minnesota composers, a conductor of Ceagerly anticipated concerts, and a recording artist, Warland has made Minnesota a national center of choral music. In so doing, he has kept an ancient tradition alive and relevant. Be sure to hear for yourself on the commemorative CD recording inside the back cover of this book. To achieve so much, an artist must have high expectations of himself and others. There is no doubt that Warland is demanding, but always in a way that is warm, human, and inspiring—that makes people want to do their best. Person after person who has been associated with Warland mentions his modesty, his quiet nature, his thoughtfulness, and his support. He leads by example. The McKnight Foundation created the Distinguished Artist Award to honor those whose lasting presence has made Minnesota a more creative, more culturally alive place. Dale Warland has conducted his Singers and others all over the world. He is internationally recognized as one of the masters of choral music. -

Atlanta Symphony Orchestra

THE UNIVERSITY MUSICAL SOCIETY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN Atlanta Symphony Orchestra YOEL LEVI Music Director and Conductor JOSHUA BELL, Violinist THURSDAY EVENING, OCTOBER 12, 1989, AT 8:00 P.M. HILL AUDITORIUM, ANN ARBOR, MICHIGAN PROGRAM Suite from The Miraculous Mandarin (1926) .......................... BARTOK Concerto in D minor for Violin and Orchestra, Op. 47 (1903) ........ SIBELIUS Allegro moderate Adagio di molto Allegro, ma non troppo JOSHUA BELL INTERMISSION Suite No. 3 in G major, Op. 55 (1884) ........................ TCHAIKOVSKY Elegie Valse melancholique Scherzo Theme and Variations Telarc, New World, Nonesuch, Pro Arte, and MMG/Vox Records. For the convenience of our patrons, the box office in the outer lobby will be open during intermission for purchase of tickets to upcoming Musical Society concerts. The piano used in this evening's concert is a Steinway available through Hammell Music, Inc. The Atlanta Symphony Orchestra is represented by Columbia Artists Management, Inc., New York City. Joshua Bell is represented by IMG Artists, New York City. Cameras and recording devices are not allowed in the auditorium. Halls Cough Tablets, courtesy of Warner Lambert Company, are available in the lobby. Third Concert of the tilth Season lllth Annual Choral Union Series PROGRAM NOTES by NICK JONES Woodruff Arts Center, Atlanta, Georgia Suite from The Miraculous Mandarin, Pantomime in One Act (to a scenario) by Menyhert Lengyel, Op. 19 ................... BELA BARTOK (1881-1945) The period immediately following the First World War was one of turmoil in all spheres, including the fine arts. In a world where governments were falling and national boundaries being redrawn, the arts reflected the general feeling that the old order was coming apart. -

The Dale Warland Singers, Friday, April 24, 1992, the Lafayette Club

• PROGRAM THE DALE WARLAND SINGERS Friday, April 24, 1992 The Lafayette Club FANFARE! a Gala Benefit and Performance for The Dale Warland Singers to celebrate their 20th anniversary season Sponsored by THE FRIENDS OF THE DALE WARLAND SINGERS 6:30 p.m. Cocktails and Silent Auction The Medicine Show Music Company 8:00 p.m. Dinner 8:30 p.m. Dinner Entertainment an_dMusic for Dancing The Jerry Rubino Trio featuring Jerry Rubino, piano Tom Larson, flute & vocals Phil Hey, drums Greg Hippen, bass Dan Chouinard, piano 9:15 p.m. Silent Auction closes, dessert is served 9:30 p.m. Entertainment Part I It's a Grand Night For Singing' Audience Sing-Along The "Rose Quartet" The "Pauls" The Warland Cabaret Singers ..Operator, Tom Larson a.k.a. "Julia" All the Things You Are New York Afternoon 9:50 p.m. Live Auction Darrah Williams, auctioneer 10: 15 p.m. Entertainment Part II The Dale Warland Singers Cindy My Lord, What a Morning Auction Winner Conducts the DWS Winner's choice of Hallelujah Chorus or America the Beautiful DWS and Wannabees sing Shenandoah The Dale Warland Singers A medley of your favorite songs by George and Ira Gershwin, arranged by Jerry Rubino Dancing follows tonight's entertainment and concludes at midnight CALL TO DINNER The Medicine Show Music Company MENU Prepared by the Lafayette Club HORS D'OEUVRES Stuffed Cherry Tomatoes, Phyllo Pastries with Crab Meat & Cream Cheese Roquefort Grapes Pea Pods stuffed with Herbed Cheese Stuffed Quail Eggs Profiterole with Chicken Salad DINNER t' Salad of Bibb Lettuce, Tomato, Hearts of Palm, . -

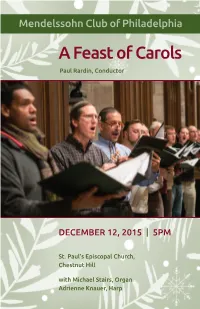

A Feast of Carols 2015

Mendelssohn Club of Philadelphia A Feast of Carols Paul Rardin, Conductor DECEMBER 12, 2015 | 5PM St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, Chestnut Hill with Michael Stairs, Organ Adrienne Knauer, Harp Today’s Concert is Presented In Memory of David Simpson Mendelssohn Club Chorus mourns the death of longtime member Dave Simpson, who passed away on December 1, 2015 from ALS. Dave was a close member of our community and sang in the chorus for 20 years. Dave’s bright personality and passion for life was an inspiration to all. Dave was a poet, musician, husband, brother, and dear friend whom we will miss greatly. From Brahms’ Ein deutsches Requiem Selig sind, die da Leid tragen, Blessed are they that mourn, den sie sollen getröstet werden. for they shall have comfort. Die mit Tränen säen, They that sow in tears, werden mit Freuden ernten. shall reap in joy. Dave, today we sing for you. DAVID SIMPSON 1952 - 2015 Dear Friends, We are so pleased to welcome you this afternoon to our annual Feast of Carols concert! Today Mendelssohn Club Chorus continues our rich holiday concert tradition, with a modern twist. Join us as we celebrate the heartwarming car- ols that we all know and love, and revel in an assortment of Christmas pieces from around the world. From well-loved carols to harp solos to spirituals to vocal jazz, this year’s Feast of Carols has a little something for everyone. We hope that you’ll leave this concert feeling warm and merry, and that the time you spend with us today is a peaceful respite from a busy season. -

A Performer's Guide to Stephen Paulus' Mad Book, Shadow Book: Songs

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2012 A performer's guide to Stephen Paulus' Mad Book, Shadow Book: Songs of Michael Morley Jin Hin Yap Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Yap, Jin Hin, "A performer's guide to Stephen Paulus' Mad Book, Shadow Book: Songs of Michael Morley" (2012). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 2278. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/2278 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. A PERFORMER’S GUIDE TO STEPHEN PAULUS’ MAD BOOK, SHADOW BOOK: SONGS OF MICHAEL MORLEY A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College In partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in The School of Music by Jin Hin Yap B.M., Louisiana State University, 2007 M.M., Louisiana State University, 2009 May 2012 ACKNOWLEDMENTS First of all, I would like to thank all my committee members. Professor Grayson, I could not say thank you enough for all the years studying with you. You saw the potential in me and helped me to become what I am as a singer and as a teacher. I will remember it for the rest of my life. -

Gerald R. Ford * 1913–2006

Gerald R. Ford o 1913–2006 VerDate jan 13 2004 11:28 Mar 20, 2008 Jkt 033200 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 8164 Sfmt 8164 C:\DOCS\FORD\33200.TXT CRS1 PsN: SKAYNE VerDate jan 13 2004 11:28 Mar 20, 2008 Jkt 033200 PO 00000 Frm 00002 Fmt 8164 Sfmt 8164 C:\DOCS\FORD\33200.TXT CRS1 PsN: SKAYNE Gerald R. Ford Late a President of the United States h MEMORIAL TRIBUTES DELIVERED IN CONGRESS VerDate jan 13 2004 11:28 Mar 20, 2008 Jkt 033200 PO 00000 Frm 00003 Fmt 8166 Sfmt 8166 C:\DOCS\FORD\33200.TXT CRS1 PsN: SKAYNE cong.17 David Hume Kennerly, courtesy Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library Gerald R. Ford VerDate jan 13 2004 11:28 Mar 20, 2008 Jkt 033200 PO 00000 Frm 00004 Fmt 8166 Sfmt 8166 C:\DOCS\FORD\33200.TXT CRS1 PsN: SKAYNE 33200.014 [110TH CONGRESS, 1ST SESSION ... HOUSE DOCUMENT NO. 110–61] MEMORIAL SERVICES IN THE CONGRESS OF THE UNITED STATES AND TRIBUTES IN EULOGY OF Gerald R. Ford LATE A PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES Compiled Under the Direction of the Joint Committee on Printing UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON : 2007 VerDate jan 13 2004 11:28 Mar 20, 2008 Jkt 033200 PO 00000 Frm 00005 Fmt 8166 Sfmt 8166 C:\DOCS\FORD\33200.TXT CRS1 PsN: SKAYNE VerDate jan 13 2004 11:28 Mar 20, 2008 Jkt 033200 PO 00000 Frm 00006 Fmt 8166 Sfmt 8166 C:\DOCS\FORD\33200.TXT CRS1 PsN: SKAYNE House Concurrent Resolution No. 128 (Mr. BRADY submitted the following concurrent resolution) IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES OF THE UNITED STATES, May 22, 2007. -

Atlanta Symphony Orchestra, Paulus Has Held Similar Positions with the Minnesota Orchestra, the Tanglewood Festival, and the Santa Fe Chamber Music Festival

STEPHEN PAULUS New World Records 80363 Concerto for Violin and Orchestra Stephen Paulus, born in Summit, New Jersey, in 1949, earned his bachelor's, master's and doctoral degrees at the University of Minnesota under such teachers as Paul Felter and Dominick Argento. He is a co-founder of the highly successful Minnesota Composers Forum, established to promote support of composers and performances of their works. Now composer in residence with the Atlanta Symphony Orchestra, Paulus has held similar positions with the Minnesota Orchestra, The Tanglewood Festival, and the Santa Fe Chamber Music Festival. His Violin Concerto won recognition in the Kennedy Center Friedheim Awards in 1988. He has received fellowships from the Guggenheim Foundation and the National Endowment for the Arts, as well as commissions from numerous musical organizations, including the Fromm Music Foundation and the Berkshire Music Center. Important among his works are his three operas; they have had successful premieres and, perhaps even more heartening, subsequent productions by other companies. Each was commissioned by the Opera Theatre of Saint Louis, whose general director, Richard Gaddes, was impressed by Paulus' cantata The North Shore, and engaged him to compose the one-act opera The Village Singer in 1979. Its success led to commissions for a two-act opera, The Postman Always Rings Twice, based on the novel by James M. Cain, and The Woodlanders, a three-act work inspired by Thomas Hardy's novel. In September 1983, Postman became the first American opera ever presented at the Edinburgh Festival. Stephen Paulus' musical style is melodic and highly rhythmic. -

[email protected] CONTACT!

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE November 19, 2012 Contact: Katherine E. Johnson (212) 875-5718; [email protected] CONTACT! THE NEW YORK PHILHARMONIC’S NEW-MUSIC SERIES Fourth Season Launches with Program by NEW YORK Composers JAYCE OGREN To Conduct in His Philharmonic Debut Two WORLD PREMIERE–New York Philharmonic COMMISSIONS: Andy AKIHO’s Oscillate and Jude VACLAVIK’s SHOCK WAVES NEW YORK PREMIERE of Andrew NORMAN’s Try DRUCKMAN’s Counterpoise Friday, December 21, 2012, at The Metropolitan Museum of Art Saturday, December 22, 2012, at Peter Norton Symphony Space WNYC’s John Schaefer To Host on December 21; Jayce Ogren To Host on December 22 Concert To Be Streamed on Q2 Music, WQXR’s Online Contemporary Music Station, December 25 at 8:00 p.m. The fourth season of CONTACT!, the Philharmonic’s new-music series, launches with a program of works exclusively by New York–based composers. American conductor-composer Jayce Ogren will make his Philharmonic debut leading the World Premieres of two Philharmonic commissions, Andy Akiho’s Oscillate and Jude Vaclavik’s SHOCK WAVES; the New York Premiere of Andrew Norman’s Try; and the ensemble version of Counterpoise by the late Jacob Druckman, Philharmonic Composer-in-Residence from 1982 to 1986, featuring soprano Elizabeth Futral. The concerts will take place Friday, December 21, 2012, at 7:00 p.m. at The Metropolitan Museum of Art and Saturday, December 22 at 8:00 p.m. at Peter Norton Symphony Space. “This program starts by bringing three talented young Americans with differing backgrounds together in a way that avoids stylistic dogmas... -

The Music of King's: Choral Favourites from Cambridge

The Choir of King’s College, Cambridge Final Logo Brand Extension Logo 06.27.12 THE MUSIC OF KING’S CHORAL FAVOURITES FROM CAMBRIDGE Stephen Cleobury THE CHOIR OF KING’S COLLEGE, CAMBRIDGE For more than half a millennium, King’s College Chapel has been the home to one of the world’s most loved and renowned choirs. Since its foundation in 1441 by the 19-year-old King Henry VI, choral services in the Chapel, sung by this choir, have been a fundamental part of life in the College. Through the centuries, people from across Cambridge, the UK and, more recently, the world have listened to the Choir at these services. Today, even people who aren’t able to attend services in the Chapel have heard King’s Choir, thanks to its many recordings and broadcasts, and the tours that have taken it to leading international concert venues around the world. Despite its deep roots in musical history, the Choir has always been at the forefront of technological innovation, and records exclusively on its ‘impeccable’ own label. 2 THE MUSIC OF KING'S The Choir of King’s College, Cambridge Stephen Cleobury conductor 3 CD 66:25 1 Cantate Domino | Claudio Monteverdi 2:09 2 Puer natus in Bethlehem | Samuel Scheidt 2:48 3 Magnificat primi toni a8 | Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina 5:31 4 Crucifixus a8 | Antonio Lotti 3:10 5 Pie Jesu (Requiem) | Gabriel Fauré 3:17 6 Ave verum corpus | Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart 2:44 7 Panis angelicus | César Franck, arr. John Rutter 3:35 8 My soul, there is a country | C.