Higher Rights of Audience Criminal Standards 2021

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Career at the Commercial Bar “…A Career Like No Other with Opportunities Like No Other …”

A CAREER AT THE COMMERCIAL BAR “…a career like no other with opportunities like no other …” 2 A CAREER AT THE COMMERCIAL BAR What is the Commercial Bar? 5 Why should you choose a career 6 at the Commercial Bar? Myths about the Commercial Bar 8 How to qualify as a barrister at the 12 Commercial Bar Useful websites 19 3 “…the front line of advocacy …” 4 WHAT IS THE COMMERCIAL BAR? he independent Bar is a law in which commercial issues arise, specialist referral profession including public law, professional Toffering expert legal advice and negligence, intellectual property, advocacy. Barristers practising at media and entertainment law and the independent Bar are self- construction. Individuals may employed but (in most cases) group specialise in particular areas within together into sets of chambers for the broad field of commercial law, and the purpose of sharing premises and specialism tends to increase other overheads. with seniority. As the law has become more complex, members of the Bar have ‘Commercial law is perhaps tended to specialise in particular areas and to form Specialist Bar best summed up as the law Associations (SBAs), of which COMBAR which applies to business is one. COMBAR now has over 1,200 members with 36 member sets of and financial disputes.’ chambers and individual members from 21 sets across London, Liverpool, Commercial barristers are usually Manchester, Birmingham, Bristol instructed by solicitors rather than and Devon. by a client directly; the services they provide fall into two main areas. First, The members of COMBAR practise and most importantly, a barrister commercial law, which is a broad is a specialist advocate who will term encompassing a wide range of present the client’s case in court. -

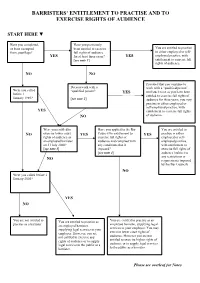

Barristers' Entitlement to Practise and to Exercise

BARRISTERS’ ENTITLEMENT TO PRACTISE AND TO EXERCISE RIGHTS OF AUDIENCE START HERE ▼ Have you completed, Have you previously or been exempted been entitled to exercise You are entitled to practise in either employed or self- from, pupillage? full rights of audience YES for at least three years? YES employed practice, with [see note 1] entitlement to exercise full rights of audience. NO NO Provided that you continue to Do you work with a work with a “qualified person” Were you called “qualified person? YES until such time as you have been before 1 entitled to exercise full rights of January 1989? [see note 2] audience for three years, you may practise in either employed or self-employed practice, with YES entitlement to exercise full rights NO of audience. Were you entitled to Have you applied to the Bar You are entitled to NO exercise lower court YES Council for entitlement to YES practise in either rights of audience as exercise full rights of employed or self- an employed barrister audience and complied with employed practice, on 31 July 2000? any conditions that it with entitlement to [see note 3] imposed? exercise full rights of [see note 4] audience (subject to any restrictions or NO requirements imposed by the Bar Council). NO Were you called before 1 January 2002? YES NO You are not entitled to You are entitled to practise as You are entitled to practise as an practise as a barrister an employed barrister, employed barrister, supplying legal supplying legal services to your services to your employer. You may employer. -

Litigants in Person

Litigants in Person Litigants in Person Key points The ‘litigant in person’ In March 2013 the Master of the Rolls issued a Practice Guidance1 which determined that the term ‘Litigant in Person’ should continue to be the sole term used to describe individuals who exercise their right to conduct legal proceedings on their own behalf. The Practice Guidance applies to all proceedings in all criminal, civil and family courts (though not curiously to tribunal proceedings), For the purposes of clarity, the term ‘litigant in person’ (as opposed to ‘self‐represented litigant’ or ‘unrepresented party’) is used in this chapter in line with the Practice Guidance both to those appearing unrepresented in courts and also in tribunals. The term encompasses those preparing a case for trial or hearing, those conducting their own case at a trial or hearing and those wishing to enforce a judgment or to appeal. Most litigants in person are stressed and worried, operating in an alien environment in what for them is a foreign language. They are trying to grasp concepts of law and procedure about which they may be totally ignorant. They may well be experiencing feelings of fear, ignorance, frustration, bewilderment and disadvantage, especially if appearing against a represented party. The outcome of the case may have a profound effect and long‐term consequences upon their life. They may have agonised over whether the case was worth the risk to their health and finances, and therefore feel passionately about their situation. Role of the judge Judges must be aware of the feelings and difficulties experienced by litigants in person and be ready and able to help them, especially if a represented party is being oppressive or aggressive. -

Solicitors' Rights of Audience, Competence and Regulation: A

Legal Studies (2021), 1–18 doi:10.1017/lst.2021.5 RESEARCH ARTICLE Solicitors’ rights of audience, competence and regulation: a responsibility rights approach Jane Ching* Nottingham Trent University, Nottingham, UK *Author e-mail: [email protected] (Accepted 22 December 2020) Abstract This paper takes as its context the decision of the Solicitors Regulation Authority in England and Wales to abandon before the event regulation of lower court trial advocacy. Although solicitors will continue to acquire rights of audience on qualification, they will no longer be required to undertake training or assessment in witness examination, by contrast with other, competing, legal professions. Their opportunities to acquire competence outside the classroom will remain limited. The paper first explores this context and its implica- tions for the three key factors of rights to perform, competence and regulatory accountability. The current regulatory system is then displayed as a Hohfeldian network of rights and duties held in tension between sta- keholders intended to inhibit the incompetent exercise of rights to conduct trial advocacy. The SRA’s proposal weakens this tension field and threatens the competitive position of solicitors. The paper therefore finally offers a radical alternative reconceptualisation of rights of audience in terms of Waldron’s ‘responsibility rights’ as a solution, albeit one with significant implications for the individual advocate. This model, applic- able globally, is closer to notions of societal good and professionalism than to those of the competitive market, whilst inhibiting incompetent performance and remediating the SRA’s approach. Keywords: trial advocacy; practice; procedure and ethics; legal regulation; legal education Introduction The legal services market in England and Wales possesses two peculiarities. -

A Comparative Study of British Barristers and American Legal Practice and Education Marilyn J

Northwestern Journal of International Law & Business Volume 5 Issue 3 Fall Fall 1983 A Comparative Study of British Barristers and American Legal Practice and Education Marilyn J. Berger Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/njilb Part of the International Law Commons Recommended Citation Marilyn J. Berger, A Comparative Study of British Barristers and American Legal Practice and Education, 5 Nw. J. Int'l L. & Bus. 540 (1983-1984) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Northwestern Journal of International Law & Business by an authorized administrator of Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. A Comparative Study of British Barristers and American Legal Practice and Education Mariyn J Berger* I. INTRODUCTION The conduct of a trial in England is undeniably an impressive un- dertaking. Costume alone transports the viewer to Elizabethan time. Counsel and judges, bewigged and gowned,' appear in a cloistered, re- gal setting, strewn with leather-bound books. Brightly colored ribbons of red, green, yellow and white, rather than metal clips and staples fasten the legal papers.2 After comparison with the volatile atmosphere and often unruly conduct of a trial in a United States courtroom, it is natural to assume that the British model of courtroom advocacy pro- * B.S., 1965, Cornell University; J.D., University of California at Berkeley. Associate Profes- sor of Law, University of Puget Sound School of Law. This article is based on the author's obser- vations and interviews while a Visiting Professor of Law at the Polytechnic of the South Bank in London, 1981-82, and a scholar-in-residence at King's College, December-June, 1982. -

Preliminary Reflections on the History of the Split English Legal Profession and the Fusion Debate (1000-1900 A.D.)

Fordham Law Review Volume 71 Issue 4 Article 7 2003 Alice's Adventures in Wonderland: Preliminary Reflections on the History of the Split English Legal Profession and the Fusion Debate (1000-1900 A.D.) Judith L. Maute Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/flr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Judith L. Maute, Alice's Adventures in Wonderland: Preliminary Reflections on the History of the Split English Legal Profession and the Fusion Debate (1000-1900 A.D.), 71 Fordham L. Rev. 1357 (2003). Available at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/flr/vol71/iss4/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. It has been accepted for inclusion in Fordham Law Review by an authorized editor of FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ALICE'S ADVENTURES IN WONDERLAND: PRELIMINARY REFLECTIONS ON THE HISTORY OF THE SPLIT ENGLISH LEGAL PROFESSION AND THE FUSION DEBATE (1000- 1900 A.D.) Judith L. Maute* Alice was beginning to get very tired of sitting by her sister on the bank, and of having nothing to do... So she was considering in her own mind ... whether the pleasure of making a daisy-chain would be worth the trouble of getting up and picking the daisies, when suddenly a White Rabbit with pink eyes ran close by her.... [W]hen the Rabbit actually took a watch out of its waistcoat-pocket, and looked at it, and then hurried on, Alice started to her feet, for it flashed across her mind that she had never before seen a rabbit with either a waistcoat-pocket, or a watch to take out of it, and, burning with curiosity, she ran across the field after it, and was just in time to see it pop down a large rabbit-hole under the hedge. -

Paper on Solicitors' Rights of Audience Prepared by the Legislative

立法會 Legislative Council LC Paper No. CB(2)438/08-09(10) Ref : CB2/PL/AJLS Panel on Administration of Justice and Legal Services Background brief for the meeting on 16 December 2008 Solicitors' rights of audience Purpose This paper provides information on the past discussion of the Panel on Administration of Justice and Legal Services (the Panel) on the issue of solicitors' rights of audience. Background The legal profession 2. The legal profession in Hong Kong is divided into two branches - barristers and solicitors. Lawyers practising within one branch of the profession are not, at the same time, allowed to practise within the other. The training and qualifications for both branches of the profession are, however, to a large extent the same, with the exception of pupilage for prospective barristers and traineeship for prospective solicitors. 3. Barristers specialise in advocacy and consultancy work. As a general rule, they cannot act directly for a client without instructions from a solicitor. They work as sole practitioners, sometimes alone but traditionally with other barristers in offices known as sets of chambers. They are not permitted to enter into partnerships. All barristers have unlimited rights of audience before the courts, i.e. they can appear on behalf of a party to proceedings in any court. 4. Solicitors can deal directly with members of the public and are mostly engaged in general practice. Solicitors may form partnerships. They have the right of audience in the magistrates' courts and the District Court, and in chambers hearings in the Court of First Instance and the Court of Appeal. -

Notes to Rights of Audience

Notes to Rights of Audience Barristers’ Entitlement to Exercise Rights of Audience This note is intended as a brief summary of the basic requirements for entitlement to exercise rights of audience as a barrister. Please see Parts II and XI of the 8th Edition of the Code of Conduct for the requirements in full. Entitlement to Exercise Full Rights of Audience Under paragraph 203.1 of the Code of Conduct, a barrister is entitled to exercise full rights of audience, provided that he: * Has completed pupillage; and * Holds a current practising certificate, issued by the Bar Council; and * Is in compliance with the “three-year rule” (para 203.1(b)) The “Three-Year Rule” The “three-year rule” is the requirement that a barrister work with a “qualified person” for his first three years’ of entitlement to exercise full rights of audience. Please note the following: * A “qualified person” is a solicitor or barrister who has practised for at least six of the last eight years and has been entitled to exercise full rights of audience for the previous two years. * A qualified person may act as such in relation to up to three barristers at a time * A qualified person must be readily available to provide guidance to the barrister(s) in question * In order to be in compliance with the “three-year rule”, a barrister’s principal place of practice must be either the principal place of practice of his qualified person or an office of an organisation of which his qualified person is an employee, partner or director. -

Rights of Audience - a Scottish Perspective

Rights of Audience - A Scottish Perspective The Right Hon. Lord Rodger of Earlsferry* It is an honour for me to have been asked to give the Child & Co. lecture. When inviting me, Sir Nicholas Phillips suggested that any talk might relate to a difference between procedures in England and Scotland. It seemed to me that some discussion of rights of audience might be suitable, since the topic is not entirely free from controversy and a speaker from a Scottish background might be able at least to supplement your thinking on the subject. First, a few words of introduction or elementary vocabulary for those contemplating the mysteries of Scots Law for the first time. In Scotland we have solicitors who correspond to solicitors in England and Wales. Advocates are the Scottish equivalent of barristers and they are all members of the Scottish Bar or Faculty of Advocates. Until the legislation on the Scottish legal profession in the Law Reform (Miscellaneous Provisions) (Scotland) Act 1990 advocates had virtually exclusive rights of audience before the Scottish supreme courts - the Court of Session in civil matters (including appeals) and the High Court of Justiciary (hereafter the High Court) in criminal matters. Similarly advocates had virtually exclusive rights of audience along with barristers before the judicial committee of the House of Lords to which an appeal lies in civil matters. 1 Even though Part II of the 1990 Act contained no new term for solicitors who obtain rights of audience before the supreme courts, the Law Society's rules approved by the Lord President of the Court of Session2 used the unlovely term "solicitor advocate" and, while some advocates have protested about this terminology, I suspect that it is here to stay and shall use it for the sake of convenience. -

A CAREER at the COMMERCIAL BAR “…A Career Like No Other a CAREER at the with Opportunities Like COMMERCIAL BAR No Other …”

A CAREER AT THE COMMERCIAL BAR “…a career like no other A CAREER AT THE with opportunities like COMMERCIAL BAR no other …” Introduction 4 What is the Commercial Bar? 5 Why should you choose a career 6 at the Commercial Bar? Myths about the Commercial Bar 8 How to qualify as a barrister at the 12 Commercial Bar Useful websites 19 2 3 INTRODUCTION WHAT IS THE COMMERCIAL BAR? Choosing a career can be daunting at the best of times. Most people will have a good idea of what a job as a doctor, teacher or engineer will involve, he independent Bar is a may also deal with other areas of but perhaps less of a feel for what specialist referral profession law in which commercial issues arise, barristers do. This brief guide to the Toffering expert legal advice including public law, professional Commercial Bar aims to help those and advocacy. Barristers practising negligence, intellectual property, who are thinking about their future at the independent Bar are self- media and entertainment law, energy vocation by explaining a little about the employed but (in most cases) group and construction. Individuals and Commercial Bar and the path that together into sets of chambers for chambers may specialise in particular is involved in pursuing a career in it. the purpose of sharing premises and areas within the broad field of other overheads. commercial law, and specialism tends The role of a barrister is an exciting one. to increase with seniority. A barrister is a specialist lawyer who is As the law has become more referred complex legal disputes by a complex, members of the Bar have ‘Commercial law is perhaps solicitor and, often, will be responsible tended to specialise in particular for presenting arguments concerning areas and to form Specialist Bar best summed up as the law that dispute in court, before a judge. -

Advocacy in the Solicitors' Profession January 2019

Advocacy in the solicitors’ profession January 2019 Contents Executive Summary .................................................................. 4 Background to the research................................................................ 4 Methodology and scope ..................................................................... 4 Key findings .................................................................................. 6 Conclusion .................................................................................. 15 1 Introduction ..................................................................... 17 1.1 Background to the research ..................................................... 17 1.2 Advocacy and the courts ......................................................... 17 1.3 Higher Rights of Audience (HRA) ................................................ 19 1.4 Criminal Advocacy – concerns and issues on the quality of advocacy ..... 20 1.5 Civil, Family and Tribunals Advocacy .......................................... 22 Civil .................................................................................................... 23 Family ................................................................................................. 23 Tribunals .............................................................................................. 24 1.6 Advocacy service providers ...................................................... 24 2 Methodology .................................................................... 26 2.1 Online -

Employed Bar A-Z Toolkit .Pdf

Employed Bar A-Z Contents Employment in Government Service ................................................................................................ 2 Entities ................................................................................................................................................... 2 Finding Support When Things Go Wrong ....................................................................................... 3 How does the Queen’s Counsel system apply to the employed Bar? .......................................... 3 How to Develop Advocacy Skills at the Employed Bar ................................................................. 4 Promotion within a corporate structure ........................................................................................... 5 Regulatory Issues ................................................................................................................................. 6 Rights of audience ................................................................................................................................ 6 The right to conduct litigation ............................................................................................................ 7 The Employed Bar A-Z Toolkit has been written by members of the Bar Council’s Employed Barrister's Committee and Young Barristers’ Committee, with input from Bar Council staff. If there are things you would like us to cover in future updates, or if you would like to comment on the material that is here, please let