Rights of Audience - a Scottish Perspective

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 Legal Terms Used in Scottish Court Procedure, Neil Kelly Partner

Legal Terms Used in Scottish Court Procedure, Neil Kelly Partner, MacRoberts Many recent reported adjudication decisions have come from the Scottish Courts. Therefore, as part of the case notes update, we have included a brief explanation of some of the Scottish Court procedures. There are noted below certain legal terms used in Scottish Court Procedure with a brief explanation of them. This is done in an attempt to give some readers a better understanding of some of the terms used in the Scottish cases highlighted on this web-site. 1. Action: Legal proceedings before a Court in Scotland initiated by Initial Writ or Summons. 2. Adjustment (of Pleadings): The process by which a party changes its written pleadings during the period allowed by the Court for adjustment. 3. Amendment (of Pleadings): The process by which a party changes its written pleadings after the period for adjustment has expired. Amendment requires leave of the Court. 4. Appeal to Sheriff Principal: In certain circumstances an appeal may be taken from a decision of a Sheriff to the Sheriff Principal. In some cases leave of the Sheriff is required. 5. Appeal to Court of Session: In certain circumstances an appeal may be taken from a decision of a Sheriff directly to the Court of Session or from a decision of the Sheriff Principal to the Court of Session. Such an appeal may require leave of the Sheriff or Sheriff Principal who pronounced the decision. Such an appeal will be heard by the Inner House of the Court of Session. 6. Arrestment: The process of diligence under which a Pursuer (or Defender in a counterclaim) can obtain security for a claim by freezing moveable (personal) property of the debtor in the hands of third parties e.g. -

A Career at the Commercial Bar “…A Career Like No Other with Opportunities Like No Other …”

A CAREER AT THE COMMERCIAL BAR “…a career like no other with opportunities like no other …” 2 A CAREER AT THE COMMERCIAL BAR What is the Commercial Bar? 5 Why should you choose a career 6 at the Commercial Bar? Myths about the Commercial Bar 8 How to qualify as a barrister at the 12 Commercial Bar Useful websites 19 3 “…the front line of advocacy …” 4 WHAT IS THE COMMERCIAL BAR? he independent Bar is a law in which commercial issues arise, specialist referral profession including public law, professional Toffering expert legal advice and negligence, intellectual property, advocacy. Barristers practising at media and entertainment law and the independent Bar are self- construction. Individuals may employed but (in most cases) group specialise in particular areas within together into sets of chambers for the broad field of commercial law, and the purpose of sharing premises and specialism tends to increase other overheads. with seniority. As the law has become more complex, members of the Bar have ‘Commercial law is perhaps tended to specialise in particular areas and to form Specialist Bar best summed up as the law Associations (SBAs), of which COMBAR which applies to business is one. COMBAR now has over 1,200 members with 36 member sets of and financial disputes.’ chambers and individual members from 21 sets across London, Liverpool, Commercial barristers are usually Manchester, Birmingham, Bristol instructed by solicitors rather than and Devon. by a client directly; the services they provide fall into two main areas. First, The members of COMBAR practise and most importantly, a barrister commercial law, which is a broad is a specialist advocate who will term encompassing a wide range of present the client’s case in court. -

2 Legal System of Scotland

Legal System of 2 Scotland Yvonne McLaren and Josephine Bisacre This chapter discusses the formal sources of Scots law – answering the question of where the law gets its binding authority from. The chapter considers the role played by human rights in the Scottish legal system and their importance both for individuals and for businesses. While most com- mercial contracts are fulfilled and do not end up in court, some do, and sometimes businesses are sued for negligence, and they may also fall foul of the criminal law. Therefore the latter part of the chapter discusses the civil and criminal courts of Scotland and the personnel that work in the justice system. The Scottish legal system is also set in its UK and European context, and the chapter links closely with Chapters 3 and 4, where two rather dif- ferent legal systems – those in Dubai and Malaysia – are explored, in order to provide some international comparisons. The formal sources of Scots Law: from where does the law derive its authority? What is the law and why should we obey it? These are important ques- tions. Rules come in many different guises. There are legal rules and other rules that may appear similar in that they invoke a sense of obligation, such as religious rules, ethical or moral rules, and social rules. People live by religious or moral codes and consider themselves bound by them. People honour social engagements because personal relationships depend on this. However, legal rules are different in that the authority of the state is behind them and if they are not honoured, ultimately the state will step in 20 Commercial Law in a Global Context and enforce them, in the form of civil remedies such as damages, or state- sanctioned punishment for breach of the criminal law. -

Statement of Standards for Solicitor Advocates – Performance Indicators

Solicitors (Scotland) Act 1980 section 25A (http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/1980/46) Rights of Audience in the Court of Session, the High Court of Justiciary, the Supreme Court and Judicial Committee of the Privy Council Statutory requirements: 1) Completion to the satisfaction of the Council of a course of training in evidence and pleading in relation to proceedings in the Courts to which rights of audience are sought 2) Has such knowledge as appears to the Council to be appropriate of (1) the practice and procedure of and (2) professional conduct in regard to those Courts 3) That the Council is satisfied that the applicant is, having regard among other things to the applicant’s experience in appropriate proceedings in the sheriff court, otherwise a fit and proper person to have a right of audience in those Courts Rules C4:1 Rights of Audience in the Civil Courts (http://www.lawscot.org.uk/rules- and-guidance/section-c-specialities/rule-c4-solicitor-advocates/rules/c41-rights-of- audience-in-the-civil-courts/), C4:2 Rights of Audience in the Criminal Courts (http://www.lawscot.org.uk/rules-and-guidance/section-c-specialities/rule-c4-solicitor- advocates/rules/c42-rights-of-audience-in-the-criminal-courts/), C4:3 Order of Precedence, Instructions (http://www.lawscot.org.uk/rules-and-guidance/section-c- specialities/rule-c4-solicitor-advocates/rules/c43-order-of-precedence,-instructions- and-representation/), and Representation and C4:4 Conduct of Solicitor Advocates (http://www.lawscot.org.uk/rules-and-guidance/section-c-specialities/rule-c4-solicitor- advocates/rules/c44-conduct-of-solicitor-advocates/) apply. -

Practice Direction 23 Court Applications

Practice Direction 23 Court Applications Date Issued: 21 June 2013 Date Implemented: 24 June 2013 Date Last Revised: 26 January 2015 SUMMARY Role of Reporters and General Principles Reporters are to: • promote the general principles in relation to the welfare of the child being paramount, views of the child and minimum intervention as they apply to court applications1, • be fair, knowledgeable and proficient in relation to relevant statutory provisions and court procedures, and • in proof applications make all reasonable efforts to bring about a prompt decision in relation to the application. Process of proof applications A proof application must be made within 7 days of the grounds hearing. The court rules set out the form of application. A proof application must be heard within 28 days of being lodged. Jurisdiction of proof applications An application in relation to offence grounds must be made to the sheriff who would have jurisdiction if the child were being prosecuted for the offence. For non-offence grounds, the application must be made to the sheriff court district where the child is habitually resident. On cause shown, the sheriff may remit any application to another sheriff court. Service, attendance and representation in proof applications The sheriff may dispense with (i) service of all or part of the application on the child, and (ii) the attendance of the child. Reporters must include information on dispensing with service and attendance in the application (if applicable). On receipt of the warrant to cite, the reporter must forthwith serve this and a copy of the application on the child (unless service has been dispensed with), each relevant person and any safeguarder. -

Foi-17-02802

Annex B Deputy First Minister’s briefing for James Wolffe meeting on 3 March 2016: Meeting with James Wolffe QC, Dean of Faculty of Advocates 14:30, 3 March 2016 Key message Support efforts to improve the societal contribution made by the courts. In particular the contribution to growing the economy Who James Wolffe QC, Dean of Faculty of Advocates What Informal meeting, principally to listen to the Dean’s views and suggestions Where Parliament When Date Thursday 3 March 2016 Time 14:30 pm Supporting Private Office indicated no officials required officials Briefing and No formal agenda agenda Annex A: Background on Faculty and biography of Mr Wolffe Annex B: Key lines Annex C: Background issues Copy to: Cabinet Secretary for Justice Minister for Community Safety and Legal Affairs DG Learning and Justice DG Enterprise, Environment and Innovation Neil Rennick, Director Justice Jan Marshall [REDACTED] Nicola Wisdahl Cameron Stewart [REDACTED] John McFarlane, Special Adviser Communications Safer & Stronger St Andrew’s House, Regent Road, Edinburgh EH1 3DG www.scotland.gov.uk MEETING WITH JAMES WOLFFE QC ANNEX A Background The Faculty of Advocates is an independent body of lawyers who have been admitted to practise as Advocates before the Courts of Scotland. The Faculty has been in existence since 1532 when the College of Justice was set up by Act of the Scots Parliament, but its origins are believed to predate that event. It is self- regulating, and the Court delegates to the Faculty the task of preparing Intrants for admission as Advocates. This task involves a process of examination and practical instruction known as devilling, during which Intrants benefit from intensive structured training in the special skills of advocacy. -

162 INTERNATIONAL LAWYER Long Before the 1957 Law, Indigent

162 INTERNATIONAL LAWYER Long before the 1957 law, indigent litigants could obtain exemption from judicial fees payable for actions in courts. The presently effective statute, 53 which dates from 1936, is part of the Code of Civil Procedure; it regulates in detail the bases on which an indigent litigant can obtain a waiver of court costs. A person who seeks legal aid either gratuitously or at a reduced rate initiates his request by obtaining from the Municipality a form, which must be filled out personally by the applicant, setting forth the financial situation on which he bases his claim that he is unable to obtain needed assistance via his own resources. Information furnished on the form is checked by the Municipality, and the application is then submitted to the consultation bureau for processing and determination of the legal aid which will be furnished. Information furnished by the applicant is further subject to examination by the court which may seek confirmation of the financial condition alleged from the tax authorities. 2. CRIMINAL MATTERS Counsel has always been available to indigent defendants in criminal matters involving a felony. 154 Within the jurisdiction of each court of first instance, a court-appointed Council for Legal Assistance functions in crim- inal matters, consisting of at least three attorneys. The Council assigns attorneys to indigent defendants in criminal matters as provided in the Code of Criminal Procedure and further as the Council may deem fit. Each defendant in provisional custody must be assigned counsel by the president of the court before which the matter will be adjudicated. -

Annual Report 2016–2017

Annual Report 2016–2017 Annual Report 2016–2017 Published pursuant to section 18 of the Judiciary and Courts (Scotland) Act 2008 Laid before the Scottish Parliament by the Scottish Ministers SG/2017/132 © Judicial Appointments Board for Scotland (JABS) copyright 2017 The text in this document (this excludes, where present, the Royal Arms and all departmental or agency logos) may be reproduced free of charge in any format or medium provided that it is reproduced accurately and not in a misleading context. The material must be acknowledged as JABS copyright and the document title specified. Where third party material has been identified, permission from the respective copyright holder must be sought. Any enquiries regarding this publication should be sent to us at: Judicial Appointments Board for Scotland Thistle House 91 Haymarket Terrace Edinburgh EH12 5HD E-mail: [email protected] This publication is only available on our website at www.judicialappointments.scot Published by the Judicial Appointments Board for Scotland, September 2017 Designed in the UK by LBD Creative Ltd Annual Report 2016–2017 Contents Our aims ii Foreword 1 Introduction and Membership 3 Committees and Groups 6 Diversity 11 Appointment Rounds 12 Meetings and Outreach 20 Tribunals 21 Complaints 22 Freedom of Information 23 Secretariat 24 Website 25 Financial Statement 26 Annex 1: Board Members and Lay Selection Panel Members 27 Annex 2: Board Member Attendance 33 i i JUDICIAL APPOINTMENTS BOARD FOR SCOTLAND Our aims are: To attract applicants of the highest calibre, to encourage diversity in the range of those available for selection, and to recommend applicants for appointment to judicial office on merit through processes that are fair, transparent and command respect. -

Scotland and the UK Constitution

Scotland and the UK Constitution The 1998 devolution acts brought about the most significant change in the constitution of the United Kingdom since at least the passage of the 1972 European Communities Act. Under those statutes devolved legislatures and administrations were created in Wales, Northern Ireland, and Scotland. The documents below have been selected to give an overview of the constitutional settlement established by the devolution acts and by the Courts. Scotland has been chosen as a case study for this examination, both because the Scottish Parliament has been granted the most extensive range of powers and legislative competences of the three devolved areas, but also because the ongoing debate on Scottish independence means that the powers and competencies of the Scottish Parliament are very much live questions. The devolution of certain legislative and political powers to Scotland was effected by the Scotland Act 1998. That statute, enacted by the Westminster Parliament, creates the Scottish Parliament and the Scottish Executive (now the “Scottish Government”), and establishes the limits on the Parliament’s legislative competence. Schedule 5 of the Act, interpolated by Section 30(1), lists those powers which are reserved to the Westminster Parliament, and delegates all other matters to the devolved organs. Thus, while constitutional matters, foreign affairs, and national defence are explicitly reserved to Westminster, all matters not listed— including the education system, the health service, the legal system, environmental -

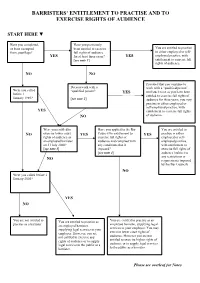

Barristers' Entitlement to Practise and to Exercise

BARRISTERS’ ENTITLEMENT TO PRACTISE AND TO EXERCISE RIGHTS OF AUDIENCE START HERE ▼ Have you completed, Have you previously or been exempted been entitled to exercise You are entitled to practise in either employed or self- from, pupillage? full rights of audience YES for at least three years? YES employed practice, with [see note 1] entitlement to exercise full rights of audience. NO NO Provided that you continue to Do you work with a work with a “qualified person” Were you called “qualified person? YES until such time as you have been before 1 entitled to exercise full rights of January 1989? [see note 2] audience for three years, you may practise in either employed or self-employed practice, with YES entitlement to exercise full rights NO of audience. Were you entitled to Have you applied to the Bar You are entitled to NO exercise lower court YES Council for entitlement to YES practise in either rights of audience as exercise full rights of employed or self- an employed barrister audience and complied with employed practice, on 31 July 2000? any conditions that it with entitlement to [see note 3] imposed? exercise full rights of [see note 4] audience (subject to any restrictions or NO requirements imposed by the Bar Council). NO Were you called before 1 January 2002? YES NO You are not entitled to You are entitled to practise as You are entitled to practise as an practise as a barrister an employed barrister, employed barrister, supplying legal supplying legal services to your services to your employer. You may employer. -

SOME OLD-TIME SCOTCH JUDGES. the Law Courts of Scotland Have

SOME OLD-TIME SCOTCH JUDGES. The Law Courts of Scotland have been as famous for the person- alities of their Judges as for the quality of the law propounded and decreed therein, and few public institutions of ancient lineage have numbered among their members so many persons of marked character and individuality as the Court of Session in Edinburgh. In Scotland individual eccentricity has never been a barrier to merit and ability in the race for fame ; on the contrary, it has often been a powerful asset, and the records of her politics and public life teem with the personal eccentricities and outstanding peculiarities of her most distinguished citizens . The Court of Session, by which term the Law Courts of Scotland are described, has held since the date of the Union of the Crowns in 17'07 and still holds, a position of peculiar dignity. Mem- bers of Parliament and the higher Civil ;Servants have had by force of circumstances their residence in London,. and accordingly for two centuries the Law Courts have been left seised of the highest social position available in the world of Edinburgh, "mine own romantic town," as Sir Walter Scott loved to call it. As a result a Lord of Session has had a special prominence in . Scotland which none save a Peer of the Realm could dispute. They not only moulded the legal traditions of the country and by their de- cision affected the tone of its administration, but their influence upon its social life has been remarkable . In their roll are to be found some unworthy and commonplace names, but many of them are well worthy of resurrection from the vaults of local history to the day- light of the present generation. -

British Institute of International and Comparative Law

BRITISH INSTITUTE OF INTERNATIONAL AND COMPARATIVE LAW PROJECT REFERENCE: JLS/2006/FPC/21 – 30-CE-00914760055 THE EFFECT IN THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITY OF JUDGMENTS IN CIVIL AND COMMERCIAL MATTERS: RECOGNITION, RES JUDICATA AND ABUSE OF PROCESS Project Advisory Board: The Rt Hon Sir Francis Jacobs KCMG QC (chair); Lord Mance; Mr David Anderson QC; Dr Peter Barnett; Mr Peter Beaton; Professor Adrian Briggs; Professor Burkhard Hess; Mr Adam Johnson; Mr Alex Layton QC; Professor Paul Oberhammer; Professor Rolf Stürner; Ms Mona Vaswani; Professor Rhonda Wasserman Project National Rapporteurs: Mr Peter Beaton (Scotland); Professor Alegría Borrás (Spain); Mr Andrew Dickinson (England and Wales); Mr Javier Areste Gonzalez (Spain – Assistant Rapporteur); Mr Christian Heinze (Germany); Professor Lars Heuman (Sweden); Mr Urs Hoffmann-Nowotny (Switzerland – Assistant Rapporteur); Professor Emmanuel Jeuland (France); Professor Paul Oberhammer (Switzerland); Mr Jonas Olsson (Sweden – Assistant Rapporteur); Mr Mikael Pauli (Sweden – Assistant Rapporteur); Dr Norel Rosner (Romania); Ms Justine Stefanelli (United States); Mr Jacob van de Velden (Netherlands) Project Director: Jacob van de Velden Project Research Fellow: Justine Stefanelli Project Consultant: Andrew Dickinson Project Research Assistants: Elina Konstantinidou and Daniel Vasbeck 1 QUESTIONNAIRE The Effect in the European Community of Judgments in Civil and Commercial Matters: Recognition, Res Judicata and Abuse of Process Instructions to National Rapporteurs Please use the following questions to describe the current position in the country for which you have been appointed as National Rapporteur. Please respond to the following questions as fully as possible, with appropriate reference to, and quotation of, supporting authority (e.g. case law and, where appropriate, the views of legal writers).