Research at Boston University 2007

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Course Revision Form 2017-2

Boston University College and Graduate School of Arts & Sciences Undergraduate Academic Program Office 725 Commonwealth Avenue, Room 102 CAS/GRS Course Revision Proposal Form To be used only for proposing a revision of a CAS course without BU Hub credit as well as for all GRS courses. This completed form and all required documents should be submitted as PDF files to either Sr. Academic Administrator Peter Law [email protected] (for CAS and CAS/GRS “piggyback” courses) or to Graduate Services Associate Casey Dziuba [email protected] (for GRS-only courses). Please contact them for information or assistance, if necessary. DEPARTMENT OR PROGRAM: Chemistry DATE SUBMITTED: 9/18/18 CURRENT COURSE NUMBER (include college code—CAS or GRS): CH 541 CURRENT COURSE NAME: Natural Products Chemistry CURRENT 40 WORD COURSE DESCRIPTION: Chemical and biosynthetic pathways leading to important natural products derived from fatty acids, terpenes, amino acids, polyketides, shikimic acid, and other biosynthetic intermediates. Three hours lecture, one hour discussion. CURRENT CROSS-LISTING DEPARTMENT/PROGRAM, if any: NA TO BE OFFERED NEXT: Sem./Year: _Fall___ /___2019_ INSTRUCTOR(S): Pinghua Liu ITEMS PROPOSED FOR REVISION (check all that apply): XX Course Number ! Credits ! Prerequisites ! Title ! Cross-listing ! Corequisites ! Short Title ! 40 Word Description ! Other (Explain) PROPOSED REVISIONS: For each item checked above, provide the current information, then the proposed information, then a brief explanation for the proposed change, including the intended impact of the change. 1. [First item checked] a. Current information: CH 541 b. Proposed information: CH 624 c. Explanation & impact: The current course number (CH 541) is out of date. -

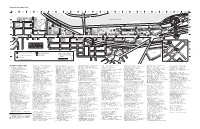

Charles River Campus Map 2010/2011 Campus Guide

Charles River Campus Map 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 Cambridge MASSACHUSETTS AVE. SOLDIERS FIELD ROAD To E A MEMORIAL DRIV A 619 M A 285 SS 120 AC 512 100 300 HU C3 S BOSTON UNIVERSITY BRIDGE ET TS ASHFORD ST. T 277 U R 519 NickersonField NP B 33 IK B BU E 531 Softball P STORROW DRIVE CHARLESGATE EAST Field 11 P 53 CHARLESGATE WEST 2 275 53 91 10 83–65 61 GARDNER ST. P 147–139 115 117 Alpert 121 125 131 P 185–167 133 RALEIGH 209–191 153 157 163 32 225 213 273 Mall 632 610 481 BAY STATE ROAD DEERFIELD ST. 70 6056 25 P 765 P 96 94–74 264 C 771 270 172–152 118–108 C 122 767 124 236–226 214–182 140 128 P 19 176 178 656 1 660 648 735 2 565 BEACON STREET To Downtown 949 925 915 P 775 GRANBY ST. Boston 1 595 P 575 1019 P P 985 881 871 855 725 705 685 675 621 SILBER WAY P ALCORN ST. 755 745 635 C4 541–533 BUICK ST. BABCOCK ST. HARRY AGGANIS WAY HARRY M1 629 625 C6 UNIVERSITY RD. C5 MALVERN ST. MALVERN P AVENUE COMMONWEALTH AVENUE Kenmore LTH COMMONWEALTH AVENUE A Square E M2 M3 M4 D W D N 940 928 890–882 846–832 808 766–730 700 P 602 580 918 115 1010 728–718 710 704 500 O P P P M 940W M M FU MOUNTFORT ST. -

Click Here to Search to Get Phone Data Faster, Please Click to Search

Click here to search To get phone data faster, please click to search button! (617) 353-4337 Available Data Avaiable More info (617) 353-1600 Executive Cleaners Boston,250 West Newton Street More info (617) 353-6062 Available Data Avaiable More info (617) 353-7804 Available Data Avaiable More info (617) 353-7049 Available Data Avaiable More info (617) 353-1076 Available Data Avaiable More info (617) 353-3263 Available Data Avaiable More info (617) 353-8798 Available Data Avaiable More info (617) 353-3601 Available Data Avaiable More info (617) 353-7099 Available Data Avaiable More info (617) 353-0295 Available Data Avaiable More info (617) 353-8756 Available Data Avaiable More info (617) 353-4570 Available Data Avaiable More info (617) 353-1133 Available Data Avaiable More info (617) 353-6973 Available Data Avaiable More info (617) 353-2593 Available Data Avaiable More info (617) 353-7937 Available Data Avaiable More info (617) 353-7516 Available Data Avaiable More info (617) 353-2180 Available Data Avaiable More info (617) 353-6465 Available Data Avaiable More info (617) 353-4129 Available Data Avaiable More info (617) 353-1056 Available Data Avaiable More info (617) 353-3469 Available Data Avaiable More info (617) 353-0590 Available Data Avaiable More info (617) 353-1338 Available Data Avaiable More info (617) 353-4224 Available Data Avaiable More info (617) 353-8792 Available Data Avaiable More info (617) 353-1290 Available Data Avaiable More info (617) 353-9225 Available Data Avaiable More info (617) 353-9631 Available Data Avaiable -

Graduate Student Handbook 2016-2017

Graduate Student Handbook 2016-2017 YOUR STUDENT CHECKLIST What? How? Who do I contact if there is a problem? Check in at the ISSO by Schedule your meeting at The International Students and Monday, September http://www.supersaas.com/schedule/buisso/Fall Scholars Office ([email protected]) 19, 2016. Bring your passport and all immigration forms. Visit the Terrier Card office in the lower level of the Student The Terrier Card Office Get your Terrier card. Union. Bring a photo ID with you. ([email protected]) Set up your BU Web The BU IT Help Center account (login and Visit the BU IT Help Center located in Mugar Library. ([email protected]) Kerberos password). Stay in Compliance: Student Accounting Services BU Student Link Confirm that you have 617-353-2264 bu.edu/studentlink paid all tuition charges. ([email protected]) Stay in Compliance: BU Student Health Services: Submit the Health Form Full-time students: follow the instructions found at 881 Commonwealth Avenue, and receive any bu.edu/shs/resources/forms/crchealthform West Entrance, required vaccinations. or 617-353-3575 Stay in Compliance: Update your BU Alert BU Student Link The BU IT Help Center phone number and bu.edu/studentlink ([email protected]) local address. Stay in Compliance: BU Student Link The BU IT Help Center Acknowledge the Mass. bu.edu/studentlink ([email protected]) Motor Vehicle Law. Check your class BU Student Link Your Departmental Academic schedule to be sure it is bu.edu/studentlink Advisor correct. Print your medical insurance Member ID BU Student Health Services: card, and keep this card Find “Boston University” and print your ID card at 881 Commonwealth Avenue, with you in case of a aetnastudenthealth.com West Entrance, medical emergency. -

Creating Our Future, 2010-2020

CREATING OUR FUTURE, 2010-2020: THE STRATEGIC PLAN OF THE COLLEGE OF ARTS & SCIENCES PART II: DEPARTMENT, PROGRAM, & OTHER UNIT PLANS April 2010 CAS Strategic Plan, 2010-2020 Part IIA: Academic Departments Table of Contents Anthropology Archaeology Art History Astronomy Biology Chemistry Classical Studies Cognitive & Neural Systems Computer Science Earth Sciences Economics English Geography & Environment History International Relations Mathematics & Statistics Modern Languages & Comparative Literature Music Philosophy Physics Political Sciences Psychology Religion Romance Studies Sociology Part IIA: Academic Departments Department of Anthropology Strategic Plan, 2010-2020 A. Mission Statement Anthropology is the study of all aspects of human life—from our biological evolution to our modern societies, religions, and economies. Our productive and respected faculty excels in strategically chosen geographic and theoretical areas in social and biological anthropology. Our teaching offers the breadth and depth to prepare undergraduate majors for graduate programs, the NGO world, and professional careers. Graduate teaching guides students toward new findings and trains them to compete for top jobs in academics and applied fields of anthropology. We also offer students across the University a basis in cultural and biological comparison. We contribute to Boston University’s missions to build global strength and develop interdisciplinary links. B. The Present 1. Peer Group We initially compared a group of 31 schools to BU as possible peers. We chose them based on relatively similar size of student body, similar size of anthropology faculty, presence of a biological anthropology program, and similar rankings from U.S. News and World Report. On this larger list, only four departments are smaller than we are, and all of those are at much smaller institutions. -

Boston University Commencement

B OSTON U NIVERSITY COMME N C EMENT 2012 SUNDAY THE TWENTIETH OF MAY ONE O’CLOCK NICKERSON FIELD BOSTON, MASSACHUSETTS CONTENTS 2 About Boston University 3 Program 4 The Metcalf Medals 5 The Metcalf Cup and Prize 6 The Metcalf Awards 8 Honorary Degrees 13 Honorary Degree Recipients of the Past 25 Years Candidates for Degrees and Certificates 15 College of Arts & Sciences 25 Graduate School of Arts & Sciences 33 College of Communication 39 School of Education 43 College of Engineering 49 College of Fine Arts 54 Henry M. Goldman School of Dental Medicine 59 School of Hospitality Administration 60 School of Law 63 School of Management 71 School of Medicine 76 Metropolitan College 86 School of Public Health 90 College of Health & Rehabilitation Sciences: Sargent College 94 School of Social Work 96 School of Theology 98 University Professors Program 99 Division of Military Education 101 Academic Traditions 102 School and College Diploma Convocations and Map 104 Prelude, Processional, and Recessional Music 105 Clarissima 106 The Corporation 1 ABOUT BOSTON UNIVERSITY Boston University’s impact extends far beyond medical college in the world. Martin Luther King, Jr., Commonwealth Avenue, Kenmore Square, and the perhaps our most famous alumnus, studied here in the Medical Campus. Our students, faculty, and alumni early 1950s, during a period when nearly half of this go all around the world to study, research, teach, and country’s doctoral degrees earned by African American become a part of the communities in which they live. students in religion and philosophy were awarded by Today, BU is the fourth-largest private university in Boston University.