THE EVOLUTIONARY DIFFERENTIATION of STRIDULATORY SIGNALS in BEETLES (Insecta : Coleoptera)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

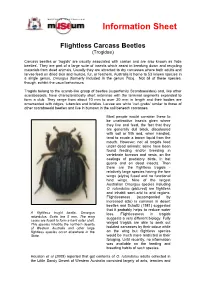

Information Sheet Flightless Carcass Beetles

Information Sheet Flightless Carcass Beetles (Trogidae) Carcass beetles or ‘trogids’ are usually associated with carrion and are also known as ‘hide beetles’. They are part of a large suite of insects which assist in breaking down and recycling materials from dead animals. Usually they are attracted to dry carcasses where both adults and larvae feed on dried skin and muscle, fur, or feathers. Australia is home to 53 known species in a single genus, Omorgus (formerly included in the genus Trox). Not all of these species, though, exhibit the usual behaviours. Trogids belong to the scarablike group of beetles (superfamily Scarabaeoidea) and, like other scarabaeoids, have characteristically short antennae with the terminal segments expanded to form a club. They range from about 10 mm to over 30 mm in length and their bodies are ornamented with ridges, tubercles and bristles. Larvae are white ‘curlgrubs’ similar to those of other scarabaeoid beetles and live in burrows in the soil beneath carcasses. Most people would consider these to be unattractive insects given where they live and feed, the fact that they are generally dull black, discoloured with soil or filth and, when handled, tend to exude a brown liquid from the mouth. However, not all trogids feed under dead animals: some have been found feeding and/or breeding in vertebrate burrows and nests, on the castings of predatory birds, in bat guano and on dead insects. Then there are the flightless trogids relatively large species having the fore wings (elytra) fused and no functional hind wings. Nine of the largest Australian Omorgus species including O. -

AND BODY of CICADA": IMPRESSIONS of the LANTERN-FLY (HEMIPTERA: FULGORIDAE) in the VILLAGE of Penna BRANCA" BAHIA STATE, BRAZIL

Journal of Ethnobiology 23-46 SpringiSummer 2003 UHEAD OF SNAKE, WINGS OF BUTTERFL~ AND BODY OF CICADA": IMPRESSIONS OF THE LANTERN-FLY (HEMIPTERA: FULGORIDAE) IN THE VILLAGE OF PEnnA BRANCA" BAHIA STATE, BRAZIL ERALDO MEDEIROS COSTA-NElO" and JOSUE MARQUES PACHECO" a Departtll'rtl?nto de Cit?t1Cias BioMgicasr Unh:rersidade Estadual de Feira de Santana, Km 3, BR 116, Campus Unirl£rsitario, eEP 44031-460, Ferra de Santana, Bahia, Brazil [email protected],br b DepartmHemo de Biowgifl Evolutim e Ecologia, Unit:rersidade Federal de Rod. Washington Luis, Km 235, Caixa Postal 676, CEP 13565~905, Sao Silo Paulo, Brazil r:~mail: [email protected] To the memory of Darrell Addison Posey (1947-2001) ABSTRACT.-Four aspects of the ethnoentomology of the lantern-fly (Fulgora la temari" L., 1767) were studied in Pedra Branca, Brazil. A total of 45 men and 41 women were consulted through open-ended interviews and their actions were observed in order to document the wisdom, beliefs, feelings, and behaviors related to the lantern-fly. People/s perceptions of the ex.temal shape of the insect influence its ethnotaxonomy, and they may categorize it into five different ethnosemantic domains, VilJagers a.re familiar with the habitat and food habits of the lantern- fly; they it lives on the trunk of Simarouba sp. (Simaroubaceae} by feeding on sap with aid of its 'sting: The culturally constructed attil:tldes toward this insect are that it is a fearsome organism that should be extlimninated .vhenever it is found because it makes 'deadly attacks.' on plants and human beings. -

Young Naturalists Teachers Guides Are Provided Free of Charge to Classroom Teachers, Parents, and Students

MINNESOTA CONSERVATION VOLUNTEER Young Naturalists Prepared by “Buggy Sounds of Summer” Jack Judkins, Multidisciplinary Classroom Activities Department of Education, Teachers guide for the Young Naturalists article “Buggy Sounds of Summer,” by Larry Weber. Illustrations by Taina Litwak. Published in the July–August 2004 Conservation Bemidji State Volunteer, or visit www.dnr.state.mn.us/young_naturalists/buggysounds University Young Naturalists teachers guides are provided free of charge to classroom teachers, parents, and students. This guide contains a brief summary of the articles, suggested independent reading levels, word counts, materials list, estimates of preparation and instructional time, academic standards applications, preview strategies and study questions overview, adaptations for special needs students, assessment options, extension activities, Web resources (including related Conservation Volunteer articles), copy-ready study questions with answer key, and a copy-ready vocabulary sheet. There is also a practice quiz (with answer key) in Minnesota Comprehensive Assessments format. Materials may be reproduced and/or modified a to suit user needs. Users are encouraged to provide feedback through an online survey at www. dnr.state.mn.us/education/teachers/activities/ynstudyguides/survey.html. Note: this guide is intended for use with the PDF version of this article. Summary “Buggy Sounds of Summer” introduces readers to crickets, katydids, and cicadas, three insects that make sounds with specialized body parts. Through photos, -

The Beetle Fauna of Dominica, Lesser Antilles (Insecta: Coleoptera): Diversity and Distribution

INSECTA MUNDI, Vol. 20, No. 3-4, September-December, 2006 165 The beetle fauna of Dominica, Lesser Antilles (Insecta: Coleoptera): Diversity and distribution Stewart B. Peck Department of Biology, Carleton University, 1125 Colonel By Drive, Ottawa, Ontario K1S 5B6, Canada stewart_peck@carleton. ca Abstract. The beetle fauna of the island of Dominica is summarized. It is presently known to contain 269 genera, and 361 species (in 42 families), of which 347 are named at a species level. Of these, 62 species are endemic to the island. The other naturally occurring species number 262, and another 23 species are of such wide distribution that they have probably been accidentally introduced and distributed, at least in part, by human activities. Undoubtedly, the actual numbers of species on Dominica are many times higher than now reported. This highlights the poor level of knowledge of the beetles of Dominica and the Lesser Antilles in general. Of the species known to occur elsewhere, the largest numbers are shared with neighboring Guadeloupe (201), and then with South America (126), Puerto Rico (113), Cuba (107), and Mexico-Central America (108). The Antillean island chain probably represents the main avenue of natural overwater dispersal via intermediate stepping-stone islands. The distributional patterns of the species shared with Dominica and elsewhere in the Caribbean suggest stages in a dynamic taxon cycle of species origin, range expansion, distribution contraction, and re-speciation. Introduction windward (eastern) side (with an average of 250 mm of rain annually). Rainfall is heavy and varies season- The islands of the West Indies are increasingly ally, with the dry season from mid-January to mid- recognized as a hotspot for species biodiversity June and the rainy season from mid-June to mid- (Myers et al. -

Animal Bioacoustics

Sound Perspectives Technical Committee Report Animal Bioacoustics Members of the Animal Bioacoustics Technical Committee have diverse backgrounds and skills, which they apply to the study of sound in animals. Christine Erbe Animal bioacoustics is a field of research that encompasses sound production and Postal: reception by animals, animal communication, biosonar, active and passive acous- Centre for Marine Science tic technologies for population monitoring, acoustic ecology, and the effects of and Technology noise on animals. Animal bioacousticians come from very diverse backgrounds: Curtin University engineering, physics, geophysics, oceanography, biology, mathematics, psychol- Perth, Western Australia 6102 ogy, ecology, and computer science. Some of us work in industry (e.g., petroleum, Australia mining, energy, shipping, construction, environmental consulting, tourism), some work in government (e.g., Departments of Environment, Fisheries and Oceans, Email: Parks and Wildlife, Defense), and some are traditional academics. We all come [email protected] together to join in the study of sound in animals, a truly interdisciplinary field of research. Micheal L. Dent Why study animal bioacoustics? The motivation for many is conservation. Many animals are vocal, and, consequently, passive listening provides a noninvasive and Postal: efficient tool to monitor population abundance, distribution, and behavior. Listen- Department of Psychology ing not only to animals but also to the sounds of the physical environment and University at Buffalo man-made sounds, all of which make up a soundscape, allows us to monitor en- The State University of New York tire ecosystems, their health, and changes over time. Industrial development often Buffalo, New York 14260 follows the principles of sustainability, which includes environmental safety, and USA bioacoustics is a tool for environmental monitoring and management. -

The Evolution and Genomic Basis of Beetle Diversity

The evolution and genomic basis of beetle diversity Duane D. McKennaa,b,1,2, Seunggwan Shina,b,2, Dirk Ahrensc, Michael Balked, Cristian Beza-Bezaa,b, Dave J. Clarkea,b, Alexander Donathe, Hermes E. Escalonae,f,g, Frank Friedrichh, Harald Letschi, Shanlin Liuj, David Maddisonk, Christoph Mayere, Bernhard Misofe, Peyton J. Murina, Oliver Niehuisg, Ralph S. Petersc, Lars Podsiadlowskie, l m l,n o f l Hans Pohl , Erin D. Scully , Evgeny V. Yan , Xin Zhou , Adam Slipinski , and Rolf G. Beutel aDepartment of Biological Sciences, University of Memphis, Memphis, TN 38152; bCenter for Biodiversity Research, University of Memphis, Memphis, TN 38152; cCenter for Taxonomy and Evolutionary Research, Arthropoda Department, Zoologisches Forschungsmuseum Alexander Koenig, 53113 Bonn, Germany; dBavarian State Collection of Zoology, Bavarian Natural History Collections, 81247 Munich, Germany; eCenter for Molecular Biodiversity Research, Zoological Research Museum Alexander Koenig, 53113 Bonn, Germany; fAustralian National Insect Collection, Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation, Canberra, ACT 2601, Australia; gDepartment of Evolutionary Biology and Ecology, Institute for Biology I (Zoology), University of Freiburg, 79104 Freiburg, Germany; hInstitute of Zoology, University of Hamburg, D-20146 Hamburg, Germany; iDepartment of Botany and Biodiversity Research, University of Wien, Wien 1030, Austria; jChina National GeneBank, BGI-Shenzhen, 518083 Guangdong, People’s Republic of China; kDepartment of Integrative Biology, Oregon State -

“Can You Hear Me?” Investigating the Acoustic Communication Signals and Receptor Organs of Bark Beetles

“Can you hear me?” Investigating the acoustic communication signals and receptor organs of bark beetles by András Dobai A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Affairs in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science In Biology Carleton University Ottawa, Ontario © 2017 András Dobai Abstract Many bark beetle (Coleoptera: Curculionidae: Scolytinae) species have been documented to produce acoustic signals, yet our knowledge of their acoustic ecology is limited. In this thesis, three aspects of bark beetle acoustic communication were examined: the distribution of sound production in the subfamily based on the most recent literature; the characteristics of signals and the possibility of context dependent signalling using a model species: Ips pini; and the acoustic reception of bark beetles through neurophysiological studies on Dendroctonus valens. It was found that currently there are 107 species known to stridulate using a wide diversity of mechanisms for stridulation. Ips pini was shown to exhibit variation in certain chirp characteristics, including the duration and amplitude modulation, between behavioural contexts. Neurophysiological recordings were conducted on several body regions, and vibratory responses were reported in the metathoracic leg and the antennae. ii Acknowledgements I would like to thank my supervisor, Dr. Jayne Yack for accepting me as Master’s student, guiding me through the past two years, and for showing endless support and giving constructive feedback on my work. I would like to thank the members of my committee, Dr. Jeff Dawson and Dr. John Lewis for their professional help and advice on my thesis. I would like to thank Sen Sivalinghem and Dr. -

Arthropod Succession on Pig Carcasses in Central Oklahoma

Forensic Entomology and its Impacts in Forensic Science Jordan Green 25 April, 2014 Entomology I Love Entomology Forensic Entomology • Branch of Zoology that studies entomological significance in criminal cases involving animal abuse, neglect, and homicide • One of the youngest and least represented branches of forensic science • Deals most heavily with: flies (Calliphoridae, Sarcophagidae, Muscidae), and beetles (Histeridae, Dermestidae, Staphylinidae) Uses for Forensic Entomology Medicocriminal: Civil Proceedings Abuse and neglect cases Homicide Investigations Photos courtesy Dr. Heather Ketchum, University of Oklahoma Blow Fly Life Cycle Stages of Decay • Fresh ---------- • Bloat • Active • Dry Fresh Staphylinidae Calliphoridae Silphidae Bloat Staphylinidae Calliphoridae Silphidae Cleridae Histeridae Sarcophagidae Active Staphylinidae Calliphoridae Silphidae Cleridae Sarcophagidae Histeridae Scarabaeidae Dermestidae Dry Silphidae Calliphoridae Scarabaeidae Nitidulidae Trogidae Cleridae Histeridae But What does it Mean? The process just described is called Succession Insect 1 Insect 2 Insect 3 Insect 2 Insect 4 Insect 3 Insect 4 Post-Mortem Interval Succession, stage of decay, and maggot development are used in the calculation of PMI Assumption: Flies detect and oviposit on corpse soon after death Question: Can post mortem interval be accurately determined using succession in homicides set in dissimilar ecological surroundings? Arthropod Activity Results • While differing habitats produced minor changes in arthropod diversity, a noticeable difference was still perceived • Differences in fly development, when coupled with temperature and relative moisture content of habitats provided accurate PMI determinations • As few as two species of fly can significantly alter PMI calculations Future Considerations • Succession studies in other environments • Changes in succession due to carcass tampering (burying, hanging, burning) • Affects of repeated desiccation and rehydration of carcasses Acknowledgements • Nadine McCrady-Borovicka, M.S. -

Coleoptera: Introduction and Key to Families

Royal Entomological Society HANDBOOKS FOR THE IDENTIFICATION OF BRITISH INSECTS To purchase current handbooks and to download out-of-print parts visit: http://www.royensoc.co.uk/publications/index.htm This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 2.0 UK: England & Wales License. Copyright © Royal Entomological Society 2012 ROYAL ENTOMOLOGICAL SOCIETY OF LONDON Vol. IV. Part 1. HANDBOOKS FOR THE IDENTIFICATION OF BRITISH INSECTS COLEOPTERA INTRODUCTION AND KEYS TO FAMILIES By R. A. CROWSON LONDON Published by the Society and Sold at its Rooms 41, Queen's Gate, S.W. 7 31st December, 1956 Price-res. c~ . HANDBOOKS FOR THE IDENTIFICATION OF BRITISH INSECTS The aim of this series of publications is to provide illustrated keys to the whole of the British Insects (in so far as this is possible), in ten volumes, as follows : I. Part 1. General Introduction. Part 9. Ephemeroptera. , 2. Thysanura. 10. Odonata. , 3. Protura. , 11. Thysanoptera. 4. Collembola. , 12. Neuroptera. , 5. Dermaptera and , 13. Mecoptera. Orthoptera. , 14. Trichoptera. , 6. Plecoptera. , 15. Strepsiptera. , 7. Psocoptera. , 16. Siphonaptera. , 8. Anoplura. 11. Hemiptera. Ill. Lepidoptera. IV. and V. Coleoptera. VI. Hymenoptera : Symphyta and Aculeata. VII. Hymenoptera: Ichneumonoidea. VIII. Hymenoptera : Cynipoidea, Chalcidoidea, and Serphoidea. IX. Diptera: Nematocera and Brachycera. X. Diptera: Cyclorrhapha. Volumes 11 to X will be divided into parts of convenient size, but it is not possible to specify in advance the taxonomic content of each part. Conciseness and cheapness are main objectives in this new series, and each part will be the work of a specialist, or of a group of specialists. -

Midsouth Entomologist 5: 39-53 ISSN: 1936-6019

Midsouth Entomologist 5: 39-53 ISSN: 1936-6019 www.midsouthentomologist.org.msstate.edu Research Article Insect Succession on Pig Carrion in North-Central Mississippi J. Goddard,1* D. Fleming,2 J. L. Seltzer,3 S. Anderson,4 C. Chesnut,5 M. Cook,6 E. L. Davis,7 B. Lyle,8 S. Miller,9 E.A. Sansevere,10 and W. Schubert11 1Department of Biochemistry, Molecular Biology, Entomology, and Plant Pathology, Mississippi State University, Mississippi State, MS 39762, e-mail: [email protected] 2-11Students of EPP 4990/6990, “Forensic Entomology,” Mississippi State University, Spring 2012. 2272 Pellum Rd., Starkville, MS 39759, [email protected] 33636 Blackjack Rd., Starkville, MS 39759, [email protected] 4673 Conehatta St., Marion, MS 39342, [email protected] 52358 Hwy 182 West, Starkville, MS 39759, [email protected] 6101 Sandalwood Dr., Madison, MS 39110, [email protected] 72809 Hwy 80 East, Vicksburg, MS 39180, [email protected] 850102 Jonesboro Rd., Aberdeen, MS 39730, [email protected] 91067 Old West Point Rd., Starkville, MS 39759, [email protected] 10559 Sabine St., Memphis, TN 38117, [email protected] 11221 Oakwood Dr., Byhalia, MS 38611, [email protected] Received: 17-V-2012 Accepted: 16-VII-2012 Abstract: A freshly-euthanized 90 kg Yucatan mini pig, Sus scrofa domesticus, was placed outdoors on 21March 2012, at the Mississippi State University South Farm and two teams of students from the Forensic Entomology class were assigned to take daily (weekends excluded) environmental measurements and insect collections at each stage of decomposition until the end of the semester (42 days). Assessment of data from the pig revealed a successional pattern similar to that previously published – fresh, bloat, active decay, and advanced decay stages (the pig specimen never fully entered a dry stage before the semester ended). -

Current Classification of the Families of Coleoptera

The Great Lakes Entomologist Volume 8 Number 3 - Fall 1975 Number 3 - Fall 1975 Article 4 October 1975 Current Classification of the amiliesF of Coleoptera M G. de Viedma University of Madrid M L. Nelson Wayne State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.valpo.edu/tgle Part of the Entomology Commons Recommended Citation de Viedma, M G. and Nelson, M L. 1975. "Current Classification of the amiliesF of Coleoptera," The Great Lakes Entomologist, vol 8 (3) Available at: https://scholar.valpo.edu/tgle/vol8/iss3/4 This Peer-Review Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Biology at ValpoScholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Great Lakes Entomologist by an authorized administrator of ValpoScholar. For more information, please contact a ValpoScholar staff member at [email protected]. de Viedma and Nelson: Current Classification of the Families of Coleoptera THE GREAT LAKES ENTOMOLOGIST CURRENT CLASSIFICATION OF THE FAMILIES OF COLEOPTERA M. G. de viedmal and M. L. els son' Several works on the order Coleoptera have appeared in recent years, some of them creating new superfamilies, others modifying the constitution of these or creating new families, finally others are genera1 revisions of the order. The authors believe that the current classification of this order, incorporating these changes would prove useful. The following outline is based mainly on Crowson (1960, 1964, 1966, 1967, 1971, 1972, 1973) and Crowson and Viedma (1964). For characters used on classification see Viedma (1972) and for family synonyms Abdullah (1969). Major features of this conspectus are the rejection of the two sections of Adephaga (Geadephaga and Hydradephaga), based on Bell (1966) and the new sequence of Heteromera, based mainly on Crowson (1966), with adaptations. -

Quick Guide for the Identification Of

Quick Guide for the Identification of Maryland Scarabaeoidea Mallory Hagadorn Dr. Dana L. Price Department of Biological Sciences Salisbury University This document is a pictorial reference of Maryland Scarabaeoidea genera (and sometimes species) that was created to expedite the identification of Maryland Scarabs. Our current understanding of Maryland Scarabs comes from “An Annotated Checklist of the Scarabaeoidea (Coleoptera) of Maryland” (Staines 1984). Staines reported 266 species and subspecies using literature and review of several Maryland Museums. Dr. Price and her research students are currently conducting a bioinventory of Maryland Scarabs that will be used to create a “Taxonomic Guide to the Scarabaeoidea of Maryland”. This will include dichotomous keys to family and species based on historical reports and collections from all 23 counties in Maryland. This document should be cited as: Hagadorn, M.A. and D.L. Price. 2012. Quick Guide for the Identification of Maryland Scarabaeoidea. Salisbury University. Pp. 54. Questions regarding this document should be sent to: Dr. Dana L. Price - [email protected] **All pictures within are linked to their copyright holder. Table of Contents Families of Scarabaeoidea of Maryland……………………………………... 6 Geotrupidae……………………………………………………………………. 7 Subfamily Bolboceratinae……………………………………………… 7 Genus Bolbocerosoma………………………………………… 7 Genus Eucanthus………………………………………………. 7 Subfamily Geotrupinae………………………………………………… 8 Genus Geotrupes………………………………………………. 8 Genus Odonteus...……………………………………………… 9 Glaphyridae..............................................................................................