An Exploratory Analysis of Children's Consumption And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Case No. 11MCV ^4

Case 1:09-cv-01024-LO-TCB Document 1 Filed 09/10/09 Page 1 of 34 PageID# 1 FILED IN THE UNITED STATES DISCTRICT COURT EASTERN DISTRICT OF VIRGINIA II? 10 \- CLl".'. Erik B. Cherdak 149 Thurgood Street Gaithersburg, Maryland 20878 Plaintiff', Pro Se, Case No. 11MCV ^4- v. COMPLAINT FOR PATENT INFRINGEMENT SKECHERS USA, INC. JURY TRIAL DEMANDED 228 Manhattan Beach Blvd. Manhattan Beach, California 90266 Defendant. SERVE ON: CORPORATION SERVICE COMPANY 11 South 12th Street P.O. Box 1463 Richmond, VA 23218-0000 COMPLAINT Plaintiff Erik B. Cherdak1 (hereinafter "Plaintiff or "Cherdak"), Pro Se, and in and for his Complaint against SKECHERS USA, INC. (hereinafter "SKECHERS"), and states as follows: JURISDICTION AND VENUE 1. This is an action for Patent Infringement under the Laws of the United States of America and, in particular, under Title 35 United States Code (Patents - 35 1 While Plaintiff Cherdak is not licensed to practice law in Virginia, he is a registered patent attorney before the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office. Case 1:09-cv-01024-LO-TCB Document 1 Filed 09/10/09 Page 2 of 34 PageID# 2 USC § 1, et seq.). Accordingly, Jurisdiction and Venue are properly based under Sections 1338(a), 1391(b) and (c), and/or 1400(b) of Title 28 of the United States Code. 2. Plaintiff is an individual who resides in Gaithersburg, Maryland at the address listed in the caption of this Complaint. At all times relevant herein, Plaintiff has been and is the named inventor of U.S. Patent Nos. 5,343,445 (the '445 patent) and 5,452,269 (the '269 patent) (hereinafter collectively referred to the "Cherdak patents," which were duly and legally issued by the U.S. -

Guía Profesional 2017 • 12€ Guía Profesional 2017 Profesional Guía

GUÍA PROFESIONAL 2017 • 12€ GUÍA PROFESIONAL 2017 PROFESIONAL GUÍA MAMADEDE F RFOM R OM RE RECYCCYCLELED D MAMADEDE F RFOM R OM RE RECYCCYCLELED D BEBEMAACHACHDE PLASTICF PLASTIC R OM RECYC LED BEBEACHACH PLASTIC PLASTIC BEACH PLASTIC O NEIO NEILL.COLL.COM/BM/BLUELUE O NEIO NEILL.COLL.COM/BM/BLUELUE O NEILL.CO M/BLUE GUÍA PROFesiOnal www.diffusionsport.com EDITA Peldaño 5 | 6 Direcciones de interés 5 Cadenas comerciales DIRECTOR DEL ÁREA 6 Grupos de compra DE DEPORTE Jordi Vilagut 7 Empresas [email protected] 69 Marcas colABORADOR José Mª Collazos índice de publicidad PUBLICIDAD Atmósfera Sport ........................................................................... 39 Pablo Prieto [email protected] Chiruca .............................................................................................. 43 Dare 2b ............................................................................................. 47 IMAGEN Y DISEÑO DS Multicanalidad ......................................................................... 63 Eneko Rojas DS Newsletter ............................................................................... 51 DS Suscripción ............................................................................... MAQUETACIÓN 68 Miguel Fariñas DS Web .............................................................................................. 59 Débora Martín FBO ...................................................................................................... 31 Verónica Gil Cristina Corchuelo Happy Dance ................................................................................. -

Black Rage VI Denison University

Denison University Denison Digital Commons Writing Our Story Black Studies 2005 Black Rage VI Denison University Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.denison.edu/writingourstory Recommended Citation Denison University, "Black Rage VI" (2005). Writing Our Story. 98. http://digitalcommons.denison.edu/writingourstory/98 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Black Studies at Denison Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Writing Our Story by an authorized administrator of Denison Digital Commons. ~It ...... 1 ei ll e:· CU· st. C jll eli [I C,I ei l .J C.:a, •.. a4 II a.il .. a,•• as II at iI Uj 'I Uj iI ax cil ui 11 a: c''. iI •a; a,iI'. u,· u,•• a: • at , 3,,' .it Statement of Purpose: To allow for a creative outlet for students of the Black Student Union of Denison University. Dedicated to Introduction The Black Student Union The need for this publication came about when the expres· Spring 2005 sions of a number of Black students were denied from other campus publications without any valid justification. As his tory has proven, when faced With limitations, we as Black people then create a means for overcoming that limitation a means that is significant to our own interests and beliefs. Therefore, we came together as a Black community in search of resolution, and decided on Black Rage as the instrument by which we would let our creative voices sing. This unprecedented publication serves as a refuge for the Black students at Denison University, by offering an avenue for our poetry, prose, short stories as well as other unique writings to be read, respected, and held in utmost regard. -

![United States Patent [19] [11] Patent Number: 5,452,269 Cherdak [45] Date of Patent: Sep](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9627/united-states-patent-19-11-patent-number-5-452-269-cherdak-45-date-of-patent-sep-1069627.webp)

United States Patent [19] [11] Patent Number: 5,452,269 Cherdak [45] Date of Patent: Sep

US005452269A United States Patent [19] [11] Patent Number: 5,452,269 Cherdak [45] Date of Patent: Sep. 19, 1995 [54] ATHLETIC SHOE WITH THVIING DEVICE 4,651,446 3/ 1987 gukawa et a1. ' 4,703,445 10/1987 assler . [75] Inventor: Erik B. Cherdak, Silver Spring, Md. 4,736,312 4/1983 Dassler et a1_ _ ‘[73] Assignees: David Stern; James Thompson, both 4’763’287 8/1988 Gerhaeuser et a1‘ ‘ fRockvine M d- 4,771,394 9/ 1988 Cavanagh . ° ’ 4,792,665 12/1988 Ruhlemann . [21] APPL No_; 297,470 4,814,661 3/1989 Ratzlaff et a1. 4,848,009 7/1989 Rodgers . [22] Filed: Aug. 29, 1994 4,876,500 10/1989 Wu . 4,891,797 1/1990 Woodfalks . Related US. Application Data illilo?g - , , a o . [63] Continuation of Ser. No. 85,936, Jul. 6, 1993, Pat. No. 5,052,131 10/1991 Rondini , 5,343,445. 5,125,647 6/1992 Smith . [51] Int. Cl.6 ...................... .. G64B 47/00; FOREIGN PATENT DOCUMENTS [52] US. Cl. .................................... .. 368/10; 368/110; W°88°4768 6/1988 WIPO ‘ 36/132; 36/137 . [58] Field Of Search ...................... .. 368/9,10,107-113; Pm”? Exam'”er“vlt W‘ M‘Ska 36/132, 136, 137, 114 [57] ABSTRACT [56] References Cited An athletic shoe which includes a timing device for US. PATENT DOCUMENTS measuring the amount of time the athletic shoe is off the D 285 142 8/1986 McAnhur ground and in air. The athletic shoe can also include a 4285b,“ 8/1981 smith ‘ ' noti?cation device which can be operatively coupled to 4,309,599 1/1982 Myers . -

K-Bay Bound After Gulf, Bangladesh, Invade': HMM-265 Heads Home and Story Photo 30

Relief society is no help without help Page A-2 DoD waives personnel cuts...for now Page 4-6 Marine boxers are Aloha State's best Page B-1 Vol. 20, No. 24 Published itt MCAS Kaneohe Bay, Also serving fat MEB, Camp H.M. Smith and Marine Barracks, Hawaii. dune 20,1991 Brits !IF K-Bay bound After Gulf, Bangladesh, invade': HMM-265 heads home and story photo 30. by Lard G. Primer Smith Mint Peelle AlnarS Office toting cyclone April H..11 M4orm 8111 The amphibious teak force Editor's note: Portions of the arrived off the Bangladesh coast MOLOKAI TRAINING following story wets excerpted May 16, joining other elements AREA, Molokai- With the from a news release from of a joint task force already in completion of a force-on -force Headquarters,Marine Corps, place to coordinate U.S. mili- Sad exercise here June 1412, a tary assistance to the relief British Army infantry company Marine Medium Helicopter efforts, and Marines from Co. L, 3d Squadron-265, the only The tITF's primary mission Battalion, 3d Marines, wrapped Brigade unit Mill de- was to provide badly needed air up three weeks of cross-training ployed that participated in and sea lifts of relief supplies during Union Pacific '91. Operation Desert Storm, will already stored at supply centers Union Pacific '91, which began return home Friday. HMM -285 in Dhaka to the devastated May 27, was one of the first was most recently deployed to islands and countryside left extensive training evolutions for Operation Sea Angel in Bang- inaccessible by the cyclone. -

The Board of Directors of the Woodlands Township and to All Other Interested Persons

NOTICE OF PUBLIC MEETING TO: THE BOARD OF DIRECTORS OF THE WOODLANDS TOWNSHIP AND TO ALL OTHER INTERESTED PERSONS: Notice is hereby given that the Board of Directors of The Woodlands Township will hold a Regular Board Workshop on Thursday, May 19, 2011, at 7:30 a.m., at the Office of The Woodlands Township, Board Chambers, 10001 Woodloch Forest Drive, Suite 600, The Woodlands, Texas, within the boundaries of The Woodlands Township, for the following purposes: 1. Call workshop session to order; 2. Consider and act upon adoption of the meeting agenda; Pages 1-6 3. Recognize public officials; 4. Public comment; POTENTIAL CONSENT AGENDA 5. Receive, consider and act upon the potential Consent Agenda; (This agenda consists of non-controversial or “housekeeping” items required by law that will be placed on the Consent Agenda at the next Board of Director’s Meeting and may be voted on with one motion. Items may be moved from the Consent Agenda to the Regular Agenda by any Board Member making such request.) a) Receive, consider and act upon approval of the minutes of the April 21, 2011 Board Workshop and April 27, 2011 Regular Board Meeting Pages 7-26 of the Board of Directors of The Woodlands Township; b) Receive, consider and act upon authorizing the annual destruction of records under an approved records retention schedule; Pages 27-28 c) Receive, consider and act upon a sponsorship agreement with Nike Pages 29-42 Team Nationals; d) Receive, consider and act upon approval of authorizing the use of an independent contractor for park and pathway maintenance contract Pages 43-44 quality inspections; 1 2 e) Receive, consider and act upon revisions to the Parks and Recreation Pages 45-48 2011 Capital Projects schedule; BRIEFINGS 6. -

Shirt - M 9001

SALE 2: 9057. *GENTS NEW 32 DEGREE COOL DARK GREY POLO SHIRT - M 9001. *GENTS NEW RED NIKE ATHLETIC TOP - M 9058. *GENTS NEW 32 DEGREE COOL DARK 9002. *GENTS NEW RALPH LAUREN WHITE T- GREY POLO SHIRT - M SHIRT - L 9059/9061. *GENTS NEW 32 DEGREE COOL 9003. *GENTS NEW UNDER ARMOUR BLUE T- DARK GREY POLO SHIRT - XXL SHIRT - M 9062. *GENTS NEW 32 DEGREE COOL GREY 9004/9008. *GENTS NEW GANT T-SHIRT BLACK - POLO SHIRT - L S 9063. *GENTS NEW 32 DEGREE COOL GREY 9009/9012. *GENTS NEW GANT T-SHIRT BLACK - POLO SHIRT - L L 9064/9066. *GENTS NEW 32 DEGREE 9013/9024. *GENTS NEW GANT T-SHIRT BLACK - COOL GREY POLO SHIRT - M S 9067. *GENTS NEW 32 DEGREE COOL GREY 9025. *GENT NEW CHAMPION WHITE T-SHIRT - POLO SHIRT - XXL S (SMALL STAIN) 9068. *GENTS NEW 32 DEGREE COOL PURPLE 9026. *GENTS NEW GANT WHITE T-SHIRT - S POLO SHIRT - L 9027/9029. *GENTS NEW GANT GREY T-SHIRT -S 9069. *GENTS NEW PUMA WHITE POLO SHIRT - M 9030. *GENTS NEW RALPH LUAREN WHITE T- 9070. *GENTS NEW PUMA GREY POLO SHIRT - SHIRT - S XXL 9031. CHILDRENS NEW BEN SHERMAN RED 9071. *GENTS NEW GANT BLACK POLO SHIRT - L POLO SHIRT - AGE 10-11 9072. *GENTS NEW GANT BLACK POLO SHIRT - M 9032. CHILDRENS NEW BEN SHERMAN POLO 9073. *GENTS NEW GANT BLACK POLO SHIRT - M SHIRT - AGE 11-12 9074. *GENTS NEW UNDER ARMOUR GREY POLO 9033. *GENTS NEW FILA BLACK POLO SHIRT - M SHIRT - S 9034. *GENTS NEW FILA BLACK POLO SHIRT - M 9075. -

E D M Hungría: Calzado

Hungría: Calzado ERCADO M E D ELABORADO POR ENERGOINFO KFT. PARA INSTITUTO ESPAÑOL DE COMERCIO EXTERIOR Con la colaboración de la Oficina Comercial de España en Budapest Abril 2000 STUDIOS E HUNGRIA: EL SECTOR DEL CALZADO INDICE 1.0 Introducción....................................................................................................................... 4 2.0 Resumen y Conclusiones ................................................................................................. 5 3.0 Panorámica del país .......................................................................................................... 7 3.1. Características generales ............................................................................................. 7 3.1.1. Características geográficas................................................................................... 7 3.1.2. Características demográficas................................................................................ 7 3.1.3. Importancia el país en la región ............................................................................ 8 3.1.4. Panorama político interior ..................................................................................... 8 3.1.5. Política internacional............................................................................................. 8 3.2. Datos macroeconómicos .............................................................................................. 9 3.2.1. Producto interior bruto ......................................................................................... -

Glendale Police Department

If you have issues viewing or accessing this file contact us at NCJRS.gov. ClPY O!.F qL'J;9{'jJ.!JL[/E • Police 'Department 'Davit! J. tJ1iompson CfUt! of Police J.1s preparea 6y tfit. (jang Investigation Unit -. '. • 148396 U.S. Department of Justice National Institute of Justice This document has been reproduced exactly as received from the person or organization originating it. Points of view or opinions stated in this document are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position or policies of the National Institute of Justice. Permission to reproduce this copyrighted material has been g~Qted bY l' . Giend a e C1ty Po11ce Department • to the National Criminal Justice Reference Service (NCJRS). Further reproduction outside of the NCJRS system requires permission of the copyright owner. • TABLEOFCON1ENTS • DEFINITION OF A GANG 1 OVERVIEW 1 JUVENILE PROBLEMS/GANGS 3 Summary 3 Ages 6 Location of Gangs 7 Weapons Used 7 What Ethnic Groups 7 Asian Gangs 8 Chinese Gangs 8 Filipino Gangs 10 Korean Gangs 1 1 Indochinese Gangs 12 Black Gangs 12 Hispanic Gangs 13 Prison Gang Influence 14 What do Gangs do 1 8 Graffiti 19 • Tattoo',;; 19 Monikers 20 Weapons 21 Officer's Safety 21 Vehicles 21 Attitudes 21 Gang Slang 22 Hand Signals 22 PROFILE 22 Appearance 22 Headgear 22 Watchcap 22 Sweatband 23 Hat 23 Shirts 23 PencHetons 23 Undershirt 23 T-Shirt 23 • Pants 23 ------- ------------------------ Khaki pants 23 Blue Jeans 23 .• ' Shoes 23 COMMON FILIPINO GANG DRESS 24 COMMON ARMENIAN GANG DRESS 25 COrvtMON BLACK GANG DRESS 26 COMMON mSPANIC GANG DRESS 27 ASIAN GANGS 28 Expansion of the Asian Community 28 Characteristics of Asian Gangs 28 Methods of Operations 29 Recruitment 30 Gang vs Gang 3 1 OVERVIEW OF ASIAN COMMUNITIES 3 1 Narrative of Asian Communities 3 1 Potential for Violence 32 • VIETNAMESE COMMUNITY 33 Background 33 Population 33 Jobs 34 Politics 34 Crimes 34 Hangouts 35 Mobility 35 Gang Identification 35 VIETNAMESE YOUTH GANGS 39 Tattoo 40 Vietnamese Background 40 Crimes 40 M.O. -

Relations Between the British and the Indian States

THE POWER BEHIND THE THRONE: RELATIONS BETWEEN THE BRITISH AND THE INDIAN STATES 1870-1909 Caroline Keen Submitted for the degree of Ph. D. at the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London, October 2003. ProQuest Number: 10731318 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10731318 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 2 ABSTRACT This thesis explores the manner in which British officials attempted to impose ideas of ‘good government’ upon the Indian states and the effect of such ideas upon the ruling princes of those states. The work studies the crucial period of transition from traditional to modem rule which occurred for the first generation of westernised princes during the latter decades of the nineteenth century. It is intended to test the hypothesis that, although virtually no aspect of palace life was left untouched by the paramount power, having instigated fundamental changes in princely practice during minority rule the British paid insufficient attention to the political development of their adult royal proteges. -

If the Shoe Fits: a Historical Exploration of Gender Bias in the U.S. Sneaker Industry

Bard College Bard Digital Commons Senior Projects Spring 2019 Bard Undergraduate Senior Projects Spring 2019 If the Shoe Fits: A Historical Exploration of Gender Bias in the U.S. Sneaker Industry Rodney M. Miller Jr Bard College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.bard.edu/senproj_s2019 Part of the Behavioral Economics Commons, Economic History Commons, Fashion Business Commons, Finance Commons, Other Economics Commons, and the Sales and Merchandising Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Miller, Rodney M. Jr, "If the Shoe Fits: A Historical Exploration of Gender Bias in the U.S. Sneaker Industry" (2019). Senior Projects Spring 2019. 80. https://digitalcommons.bard.edu/senproj_s2019/80 This Open Access work is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been provided to you by Bard College's Stevenson Library with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this work in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights- holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. For more information, please contact [email protected]. If the Shoe Fits: A Historical Exploration of Gender Bias in the U.S. Sneaker Industry Senior Project Submitted to The Division of Social Studies of Bard College by Rodney “Merritt” Miller Jr. Annandale-on-Hudson, New York May 2018 ii iii Acknowledgements To my MOM, Jodie Jackson, thank you for being the best mom and support system in the world. -

Glossary of Shoe Terms

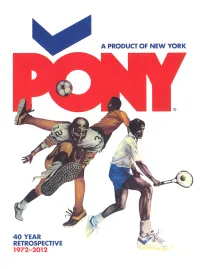

SNEAKER FREAKER PRESENTS WRITTEN, DESIGNED AND EDITED BY SNEAKER FREAKER FOR PONY. EDITOR WOODY CONTRIBUTORS ANTHONY COSTA, JAMES CHAN DESIGN TERRY RICARDO THANKS RICKY POWELL, BOBBITO GARCIA, ROBERTO MULLER, SPUD WEBB, DEE and RICKY AND MIKE PACKER. ©SNEAKER FREAKER 2012 REPRODUCTION IS STRICTLY PROHIBITED WITHOUT PRIOR ESTABLISHED 1972 PERMISSION. THE VIEWS EXPRESSED ARE THOSE OF THE CONTRIBUTORS AND NOT NECESSARILY THOSE OF THE PUBLISHER. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. 2012. CONTENTS A PRODUCT OF NEW YORK • 07 • ROBERTO MULLER the foUNDER OF PONY • 18 • SPUD WEBB SLAM DUNK • 34 • PEOPLE OF NEW YORK BOBBITO GARCIA • 42 • RICKY POWELL • 50 • DEE & RICKY • 56 • VINTAGE PONY SNEAKERS • 60 • VINTAGE ADS • 104 • VINTAGE CATALOGUES • 122 • C USTOM SNEAKERS • 138 • 40 YeARS Of pony A PRODUCT OF NEW YORK B orn in Manhattan back in 1972, long But first, let’s rewind this story to 1969, a year before anyone gave a flying Swoosh, of monumental unrest and social change in the Pony was founded by Uruguay-born USA. Richard Nixon was elected president, Neil entrepreneur Roberto Muller, a Armstrong stepped on the moon and New York was charismatic maverick who lived life at the epicentre of a rare sporting triple triumph. The New York Mets took home the World Series, by the seat of his pants. Literally the Super Bowl III was won by the New York Jets then heart and sole of the company, Muller the following year the New York Knicks bagged their created Pony in his own image, which first title. It was an incredible sequence. is to say it was equal-parts energetic, Meanwhile, the staid athletic industry plodded rambunctious and oh-so-ambitious.