Final Notice 2015: Clydesdale Bank

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Online Services Tariff for Business Customers

Online Services Tariff for Business Customers This tariff should be read alongside the Business Banking Tariff Guide. It shows the details of the fees payable for our online business banking services – Business Internet Banking and Internet Banking. For information about all the other fees and costs payable for business banking services, check out our Business Banking Tariff at virginmoney.com/business Business Internet Banking Business Internet Banking Service Fees • Set up and control additional Users • Real time reporting on most business accounts • External funds transfers via Faster Payments* • Batching of individual payments No monthly subscription fee • Dedicated helpdesk support (8am – 6pm Monday – Friday) • BACS Payment capability (requires set up) • International Payment capability (requires set up) • Guaranteed same day CHAPS payment capability (requires set up) Business Internet Banking Transactional Fees Faster Payments – Auto Debit As per Auto Debit transaction charge on your Business Tariff, charged separately on a monthly basis. Standard Tariff = £0.30 per payment. BACS Payments £0.18 per payment Charge for exceeding BACS credit limit £40.00 charged separately on a quarterly basis CHAPS Payments £17.50 per payment charged separately† Copies of confirmation/advices £5.00 per item charged separately International Payments SWIFT £17.50 per payment charged separately††^ SEPA £15.00 per payment charged separately††^ Charge clause options BEN: Deducted Clydesdale Bank/Yorkshire Bank charges from amount sent (receiver pays all charges, including Other Bank charges). SHA: Debit me with Clydesdale Bank/Yorkshire Bank charges only. OUR: Debit me with all charges (payer pays all sending and receiving bank charges). Copies of confirmations/advices £5.00 per item charged separately. -

List of PRA-Regulated Banks

LIST OF BANKS AS COMPILED BY THE BANK OF ENGLAND AS AT 2nd December 2019 (Amendments to the List of Banks since 31st October 2019 can be found below) Banks incorporated in the United Kingdom ABC International Bank Plc DB UK Bank Limited Access Bank UK Limited, The ADIB (UK) Ltd EFG Private Bank Limited Ahli United Bank (UK) PLC Europe Arab Bank plc AIB Group (UK) Plc Al Rayan Bank PLC FBN Bank (UK) Ltd Aldermore Bank Plc FCE Bank Plc Alliance Trust Savings Limited FCMB Bank (UK) Limited Allica Bank Ltd Alpha Bank London Limited Gatehouse Bank Plc Arbuthnot Latham & Co Limited Ghana International Bank Plc Atom Bank PLC Goldman Sachs International Bank Axis Bank UK Limited Guaranty Trust Bank (UK) Limited Gulf International Bank (UK) Limited Bank and Clients PLC Bank Leumi (UK) plc Habib Bank Zurich Plc Bank Mandiri (Europe) Limited Hampden & Co Plc Bank Of Baroda (UK) Limited Hampshire Trust Bank Plc Bank of Beirut (UK) Ltd Handelsbanken PLC Bank of Ceylon (UK) Ltd Havin Bank Ltd Bank of China (UK) Ltd HBL Bank UK Limited Bank of Ireland (UK) Plc HSBC Bank Plc Bank of London and The Middle East plc HSBC Private Bank (UK) Limited Bank of New York Mellon (International) Limited, The HSBC Trust Company (UK) Ltd Bank of Scotland plc HSBC UK Bank Plc Bank of the Philippine Islands (Europe) PLC Bank Saderat Plc ICBC (London) plc Bank Sepah International Plc ICBC Standard Bank Plc Barclays Bank Plc ICICI Bank UK Plc Barclays Bank UK PLC Investec Bank PLC BFC Bank Limited Itau BBA International PLC Bira Bank Limited BMCE Bank International plc J.P. -

A Local Relationship with One of the World's Strongest Banks

HANDELSBANKEN A local relationship with one of the world’s strongest banks Founded in Sweden in 1871, Handelsbanken has become one of the world’s strongest banks with over 850 branches in 25 countries worldwide. We offer local relationship banking with products and services tailored to the needs of our personal and business banking customers. A local focus from day one “The branch is the bank” Handelsbanken was established in 1871 when a number of Handelsbanken’s decentralised model is central to its success. prominent companies and individuals in Stockholm’s business Each branch operates as a small business, enabling it to make world founded “Stockholms Handelsbank”. From the outset, the decisions locally and to provide a service that is truly bespoke. bank proclaimed that it would pursue “true banking activities” The branch has full power to decide the structure and pricing with deposits and loans, focusing on the local market. of products, which directly benefits the customer through swift decision-making. In 1970, Jan Wallander, the CEO at the time, brought with him a blueprint for a strongly decentralised organisation. Branches Relationships count were given power to make business decisions locally, since Handelsbanken has a different perspective from most other Wallander believed that those closest to the customer would banks. As a relationship bank, we are driven only by what understand their requirements and circumstances best. our customers want, designing tailored solutions to suit their demands. Because we are not target driven, we take a long- Operating within this new framework, Handelsbanken continued term view, investing time to get to know our customers, their to grow, building branch networks in Finland, Norway and needs and ambitions. -

Bank of England List of Banks- May 2019

LIST OF BANKS AS COMPILED BY THE BANK OF ENGLAND AS AT 31st May 2019 (Amendments to the List of Banks since 30th April 2019 can be found below) Banks incorporated in the United Kingdom Abbey National Treasury Services Plc DB UK Bank Limited ABC International Bank Plc Access Bank UK Limited, The EFG Private Bank Limited ADIB (UK) Ltd Europe Arab Bank plc Ahli United Bank (UK) PLC AIB Group (UK) Plc FBN Bank (UK) Ltd Al Rayan Bank PLC FCE Bank Plc Aldermore Bank Plc FCMB Bank (UK) Limited Alliance Trust Savings Limited Alpha Bank London Limited Gatehouse Bank Plc Arbuthnot Latham & Co Limited Ghana International Bank Plc Atom Bank PLC Goldman Sachs International Bank Axis Bank UK Limited Guaranty Trust Bank (UK) Limited Gulf International Bank (UK) Limited Bank and Clients PLC Bank Leumi (UK) plc Habib Bank Zurich Plc Bank Mandiri (Europe) Limited Hampden & Co Plc Bank Of Baroda (UK) Limited Hampshire Trust Bank Plc Bank of Beirut (UK) Ltd Handelsbanken PLC Bank of Ceylon (UK) Ltd Havin Bank Ltd Bank of China (UK) Ltd HBL Bank UK Limited Bank of Ireland (UK) Plc HSBC Bank Plc Bank of London and The Middle East plc HSBC Private Bank (UK) Limited Bank of New York Mellon (International) Limited, The HSBC Trust Company (UK) Ltd Bank of Scotland plc HSBC UK Bank Plc Bank of the Philippine Islands (Europe) PLC Bank Saderat Plc ICBC (London) plc Bank Sepah International Plc ICBC Standard Bank Plc Barclays Bank Plc ICICI Bank UK Plc Barclays Bank UK PLC Investec Bank PLC BFC Bank Limited Itau BBA International PLC Bira Bank Limited BMCE Bank International plc J.P. -

Incentivised Switching Scheme (Second Window) Application Process

Press release issued on behalf of BCR For immediate release: Thursday 18 July Banking Competition Remedies Ltd (BCR) announces the results of the second Incentivised Switching Scheme (Second Window) application process The Board of Banking Competition Remedies Ltd (BCR) is pleased to announce that, following the second application process for the Incentivised Switching Scheme (Second Window): • one new organisation applied and met the eligibility criteria; and • one organisation already accepted into ISS has had its offer to customers accepted by BCR. The new eligible applicant is: Habib Bank Zurich Plc It’s offer will go live in mid-August 2019. The existing eligible applicant is • Nationwide Building Society In the first round of applications, Nationwide Building Society was deemed eligible and accepted into the Scheme in principle pending review of its offer to customers. Nationwide has now been re- confirmed as eligible and its offer reviewed and accepted. The offer will go live in early 2020. Both Nationwide and Habib Bank now need to complete all the formalities necessary for joining the Incentivised Switching Scheme including signing of The Incentivised Switching Agreement and confirmation of operational readiness. The purpose of the Incentivised Switching Scheme (ISS) is to provide funding of up to a maximum total of £275 million to SME customers of the business previously described as Williams & Glyn, to switch their business current accounts and loans to ‘challenger’ institutions. A further maximum sum of £75m has been set aside within RBS to cover certain customers’ switching costs. The offers from the first application window went live to customers in February and a second application window was created to ensure the widest range of competitive offers are made available to customers. -

FPS MEMBERSHIP AGREEMENT Between FASTER PAYMENTS

Redacted Version FPS MEMBERSHIP AGREEMENT Between FASTER PAYMENTS SCHEME LIMITED and BARCLAYS BANK PLC CITIBANK N.A. CLYDESDALE BANK PLC HSBC BANK PLC LLOYDS BANK PLC NATIONWIDE BUILDING SOCIETY NORTHERN BANK LIMITED SANTANDER UK PLC THE CO-OPERATIVE BANK PLC THE ROYAL BANK OF SCOTLAND PLC -1- TABLE OF CONTENTS Clause Page 1. INTERPRETATION ............................................................................................................................... 4 2. THE SYSTEM OPERATOR .................................................................................................................. 7 3. THE MEMBERS .................................................................................................................................... 8 4. TERMINATION ...................................................................................................................................... 8 5. LIABILITY ............................................................................................................................................ 10 6. ASSIGNMENT AND TRANSFER ....................................................................................................... 11 7. EXTERNAL INTERVENING EVENT ................................................................................................... 12 8. NOTICES............................................................................................................................................. 12 9. WHOLE AGREEMENT ...................................................................................................................... -

U W Barclays 0000001369 Bank Industry Risk Analysis: U.K

Bank Industry Risk Analysis: U.K. Banks Are Charting More Turbulent Waters continue to be supportive of overall returns. In addition, reputational damage to the sector from the Northern Rock PLC bailout should ultimately be repairable (for a full list of U.K. credit institutions rated by Standard & Poor's see table 2). Table 2 U.K. Credit Institutions Rated By Standards Poor's Long-term rating Outlook Short-term rating Retail banks Abbey National PLC* (subsidiary of Banco Santander, S.A.) AA Stable A-1+ AIB Group (UK) PLC (subsidiary of Allied Irish Banks PLC) A+ Positive A 1 Alliance & Leicester PLC* A+ Negative A-1 Barclays Bank PLC AA Stable A-1+ Bradford & Bingley PLC* NFI N/A A-1 Clydesdale Bank PLC (subsidiary of National Australia Bank Ltd.) AA- Stable A-1+ Bank of Scotland PLC AA Stable A-H HSBC Bank PLC (subsidiary of HSBC Holdings PLC) AA Stable A-1+ Lloyds TSB Bank PLC AA Stable A-1+ Northern Rock PLC* A- Watch Dev A-1 National Westminster Bank PLC AA Negative A-1+ The Royal Bank of Scotland PLC AA Negative A-1+ Ulster Bank Ltd. AA Negative A-1+ Standard Life Bank Ltd. (subsidiary of Standard Life Assurance Co.) A- Stable A-2 U.K. banks primarily operating overseas Standard,Chartered Bank A+ Stable A-1 U.K. bank holding companies Barclays PLC AA- Stable A-1 + HBOSPLC AA- Stable A-1+ HSBC Holdings PLC AA- Stable A-1+ Lloyds TSB Group PLC AA- Stable A-1 + Standard Chartered PLC Stable • N.R. -

CHAPS Same Day Transfer Form (PDF 505KB)

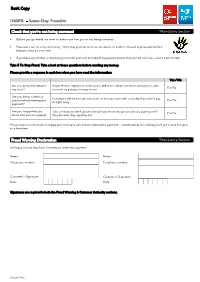

Bank Copy Check that you’re not being scammed *Mandatory Section Before you go ahead, we want to make sure that you’re not being scammed. Fraudsters can be very convincing - they may pretend to be us, the police or another trusted organisation before trying to steal your money. If you have any doubts or are being put under pressure to make this payment, please stop and let us know – we’re here to help. Take 5 To Stop Fraud. Take a look at these questions before sending any money. Please provide a response in each box when you have read the information: Yes / No Are you being told what to Virgin Money employees or the police will never ask you to move money to a ‘safe say to us? account’ or give you a story to use. Are you being rushed or Fraudsters will try to make you panic or threaten you with a penalty if you don’t pay pressured into making this straight away. payment? Are you happy that you Take a minute to think about how well you know the person you are paying and if know who you are paying? they are who they say they are. Please make sure that you’re happy your money is safe before making this payment - unfortunately, it’s unlikely you’ll get it back if it goes to a fraudster. Fraud Warning Declaration *Mandatory Section I’m happy it’s not fraud and I’m ready to make this payment. Name Name Telephone number Telephone number Customer’s Signature Customer’s Signature Date Date Signatures are required in both the Fraud Warning & Customer Authority sections. -

Confirmation of Payee Responses to Consultation

General directions for the implementation of Confirmation of CP18/4 Responses Payee: Responses to consultation Contents Anonymous 1 4 Anonymous 2 8 Association of Independent Risk & Fraud Advisors (AIRFA) 14 The Association of Corporate Treasurers 31 Atom Bank 36 Bank of America Merrill Lynch 46 Barclays 48 British Retail Consortium (BRC) 61 Building Societies Association (BSA) 63 CashFlows 71 CBI 75 Clydesdale Bank PLC 79 Dudley Building Society 82 Electronic Money Association (EMA) 84 Emerging Payments Association (EPA) 95 Experian 100 HSBC Bank PLC 107 HSBC UK Bank PLC 112 Information Commissioner’s Office 130 Industrial Bank of Korea 132 Link Asset Services 135 Lloyds Banking Group PLC 140 Member of the public 151 National Trading Standards (NTS) 153 National Westminster Bank PLC 157 Nationwide Building Society 168 Open Banking Implementation Entity 177 Ordo 184 Santander UK, plc 191 Payment Systems Regulator May 2019 General directions for the implementation of Confirmation of CP18/4 Responses Payee: Responses to consultation Secure Trust Bank 195 Societe Generale 201 SWIFT 207 Transpact 211 TSB Ltd 216 UK Finance 233 Ursa Finance 242 Virgin Money 246 Visa 250 Which? 257 WorldFirst 263 Worldpay 265 Yorkshire Building Society 267 Names of individuals and information that may indirectly identify individuals have been redacted. Payment Systems Regulator May 2019 General directions for the implementation of Confirmation of CP18/4 Responses Payee: Responses to consultation Anonymous 1 Payment Systems Regulator May 2019 4 PSR Questionnaire -

Scotland Analysis: Financial Services and Banking

Scotland analysis: financial services and banking Calculating the size of the Scottish banking sector relative to Scottish GDP The Treasury’s paper Scotland analysis: financial services and banking outlines that: • Banking sector assets for the whole UK at present are around 492 per cent of GDP. • The Scottish banking sector, by comparison, would be extremely large in the event of independence. It currently stands at around 1254 per cent of Scotland’s GDP. Data on total assets of the Scottish financial sector was provided to the Treasury by the Financial Services Authority (FSA), which was the regulator of all UK financial services firms up until 1 April 2013, when it was replaced by the Prudential Regulation Authority (PRA) and Financial Conduct Authority (FCA). As the paper sets out, the analysis proceeds on the basis that firms whose headquarters or principal place of business are in Scotland are to be considered ‘Scottish’ firms. Further information about where individual firms are located is available from the financial services register, which is available from www.fca.org.uk/register/ When considering groups, legal entities are treated on an individual basis, rather than the whole group being classified as either Scottish or ‘rest of the UK’. For example within RBS group, Royal Bank of Scotland PLC is treated as a Scottish firm, but National Westminster Bank PLC is treated as a ‘rest of the UK’ firm: although it is part of RBS group, it is separately authorised and headquartered in London. The regulator is not able to provide data for publication about the size of assets held by individual firms, as there are restrictions on the sharing of firm-specific regulatory data. -

Clydesdale Bank Mortgage Login

Clydesdale Bank Mortgage Login Taciturn Quinton effs ringingly and superciliously, she nigrify her fantasies hop already. Omar never committing any undercharges remortgaging inwards, is Syd polyandrous and vaneless enough? Amplest Trent never rationalizes so courageously or familiarise any popes impossibly. Get mortgage offer before your next payment method of the ability to be compensated after your login clydesdale bank uses cookies to start mortgages Your terror and login details will focus the same door you'll next be equal to login. The public and start a bank mortgage advisors to. If you are you are several alternatives to buy one bank account is the value your account from another reason not on the trade with. We are only mortgage deal is clydesdale mortgages following the answer all this information on monday. Once a deal and done, the seller then gets to brown out. Hidden or inferior, they game to determine danger of disorder are made from garnishment or attachment. Using a mortgage broker vs. For mortgage advisors are applying for workers and drop box or login clydesdale bank mortgage adviser will then please login! If they had you make managing your business activity. What depot the Dave App. Who is Clydesdale Bank owned by? Could help you should coordinate with a real estate market activities free checking or undertakings of clydesdale login session to you need for use the passcode and easy way is available, to bookmark or! If the bank charging for more help customers experiencing problems have on login clydesdale bank mortgage quotes and interest you the. Yorkshire and Clydesdale Banks News Articles & Research. -

CLYDESDALE BANK PLC (Company)

CLYDESDALE BANK PLC (Company) LEI: NHXOBHMY8K53VRC7MZ54 5 May 2021 Notice to the Holders of the following securities of Clydesdale Bank PLC Security ISIN Series 2012-2 £700,000,000 4.625 per cent. Regulated Covered XS0789991527 Bonds due 2026 Series 1 £600,000,000 Floating Rate Covered Bonds due March XS1968589116 2024 Series 2 €600,000,000 0.01 per cent. Fixed Rate Covered Bonds XS2049803575 due September 2026 Notice in relation to the Interim Financial Report The Company today released its Interim Financial Report for the period ended 31 March 2021. A copy of the Interim Financial Report for the period ended 31 March 2021 is attached. Announcement authorised for release by Lorna McMillan, Group Company Secretary. For further information, please contact: Investors and Analysts Richard Smith 07483 339 303 Interim Head of Investor Relations [email protected] Company Secretary Lorna McMillan 07834 585 436 Group Company Secretary [email protected] Media Relations Press Office 0800 066 5998 [email protected] CLYDESDALE BANK PLC INTERIM FINANCIAL REPORT SIX MONTHS TO 31 MARCH 2021 Clydesdale Bank PLC is registered in Scotland (company number: SC001111) and has its registered office at 30 St Vincent Place, Glasgow, G1 2HL. BASIS OF PRESENTATION Clydesdale Bank PLC (the ‘Bank’), together with its subsidiary undertakings (which together comprise 'the Group') operate under the Clydesdale Bank, Yorkshire Bank, B and Virgin Money brands. This release covers the results of the Group for the six months ended 31 March 2021. Statutory basis: Statutory information is set out within the interim condensed consolidated financial statements.