Boal in the Classroom: a Technique for Developing a Teen Theatre Project

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Oferta Para Aspirantes a Interinidades 2016/2017 Aviles Aviles Boal Cangas De Onis Carreño Castrillon Aviles Aviles Boal Cang

Gobierno del Principado de Asturias CONSEJERÍA DE EDUCACIÓN Y CULTURA OFERTA PARA ASPIRANTES A INTERINIDADES 2016/2017 18-OCT-16 AVILES AVILES 33001393 I.E.S. "CARREÑO MIRANDA" Código Especialidad Iti Jornada Función 054152 V 0590 004 LENGUA CASTELLANA Y LITERATURA N 054345 0590 006 MATEMATICAS N Por centro hay 2 especialidades y 2 vacantes totales AVILES AVILES 33022086 C.P. "VERSALLES" Código Especialidad Iti Jornada Función 766806 0597 038 EDUCACIÓN PRIMARIA N Por centro hay 1 especialidades y 1 vacantes totales BOAL BOAL 33027369 C.P.E.B. "CARLOS BOUSOÑO" Código Especialidad Iti Jornada Función 036870 V 0590 803 CULTURA CLASICA N H Por centro hay 1 especialidades y 1 vacantes totales CANGAS DE ONIS CANGAS DE ONIS 33023650 I.E.S. "REY PELAYO" Código Especialidad Iti Jornada Función 054160 0590 008 BIOLOGIA Y GEOLOGIA N 0590011 Por centro hay 1 especialidades y 1 vacantes totales CARREÑO CANDAS 33003638 C.P. "San Félix" Código Especialidad Iti Jornada Función 766822 0597 034 EDUCACIÓN FÍSICA N Por centro hay 1 especialidades y 1 vacantes totales CASTRILLON SALINAS 33004141 I.E.S. de Salinas Código Especialidad Iti Jornada Función 054175 V 0590 004 LENGUA CASTELLANA Y LITERATURA N Por centro hay 1 especialidades y 1 vacantes totales Página 1 de 8 Gobierno del Principado de Asturias CONSEJERÍA DE EDUCACIÓN Y CULTURA OFERTA PARA ASPIRANTES A INTERINIDADES 2016/2017 18-OCT-16 COAÑA JARRIO 33004539 C.P. "Darío Freán Barreira" Código Especialidad Iti Jornada Función 766845 0597 034 EDUCACIÓN FÍSICA N 766830 0597 038 EDUCACIÓN PRIMARIA N Por centro hay 2 especialidades y 2 vacantes totales CORVERA DE ASTURIAS CAMPOS(LOS) 33023972 I.E.S. -

Artículu 13-José Ramón López Blanco-Ñomatos N´Asturies.Pdf

Árabes (por burros). Caliao (Casu). Arandaneros La Cerezal (Samartín del Rei Aurelio). Pola bayura d'arándanos. Paez que dal- gunes veces, cuandu La Cerezal yera de la parroquia de Blimea (psó'n 1955 a la de Santa Bálbola), los de Sanamiés, tamién Ñomatos n9Asturies d'aquella parroquia, poníense nun sitiu lla- máu La Muezca y burllábense d'ellos vocian- do asina: «Arandanirus, arandanirus, tiras- GosÉ RAMÓNLÓPEZ BLANCO teis el santu al reguirux. Arameñoes Santa Comba (Ibias). Areñascos L'Arena (Sotu'l Barcu). Fago rellación de toa una riestra ñomatos con que son conocíos los vecinos de dellos pueblos, parroquies y conce- Árgomas Oteda, Francos (Tinéu). yos en conxuntu. La bayura d'éstos ye perestimable n'Astu- Arrieiros Bayu (Grao). ries, anque la mio referencia, comu ye lo normal, nun da Axeldos Cadagayoso y Vilarmeirín (Ibias). cuenta de toos. Por tar asitiaos onde nun da'l sol. La gran mayoría d'estos ñomatos llogréla gracies a les Ayunquinos Tiós (Llena). referencies daes per amigos o conocíos en conversaciones Azaquiles Fombermeya (Llaviana). particulares. Otres vegaes dalgún datu tómolu de delles no- ticies escrites. Boca negra Casu. (Los de la-) Dicen que por tener la boca prieta les va- Abecudos Abéu (Ribesella). ques casines. Afumaos Coañana (Quirós); San Rque L'Acebal (Lla- Cabreiros L!arón (Cangas del Narcea). nes). Cabritones Buspriz (Casu). De los d'esti últimu llugar dicen que los «Vamos a Buspgz, / los de les cervices ñomen asina porque too aquello ta mui po- llargues (como les cabra), / que cuchen en blao d'árboles que mirando dende lloñe nun llurnbu / y echen les entrañes)) (M. -

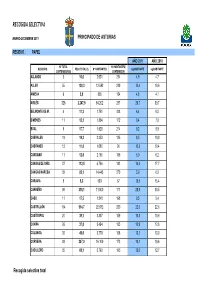

Recogida Selectiva

RECOGIDA SELECTIVA ENERO-DICIEMBRE 2011 PRINCIPADO DE ASTURIAS RESIDUO : PAPEL AÑO 2011 AÑO 2010 Nª TOTAL Nº HABITANTES/ MUNICIPIO PESO TOTAL (t) Nº HABITANTES kg/HABITANTE kg/HABITANTE CONTENEDORES CONTENEDOR ALLANDE 8 10,0 2.031 254 4,9 4,7 ALLER 55 130,3 12.582 229 10,4 10,6 AMIEVA 6 3,9 805 134 4,8 4,1 AVILÉS 328 2.247,9 84.202 257 26,7 30,7 BELMONTE DE M. 4 11,3 1.751 438 6,4 6,8 BIMENES 11 12,1 1.894 172 6,4 7,0 BOAL 9 17,7 1.928 214 9,2 9,9 CABRALES 18 19,2 2.253 125 8,5 10,9 CABRANES 12 11,8 1.080 90 10,9 10,4 CANDAMO 11 12,8 2.160 196 5,9 6,2 CANGAS DE ONÍS 37 112,5 6.756 183 16,6 17,7 CANGAS NARCEA 39 85,1 14.445 370 5,9 6,0 CARAVIA 8 8,3 533 67 15,5 15,4 CARREÑO 99 318,1 11.000 111 28,9 30,5 CASO 11 17,5 1.848 168 9,5 9,4 CASTRILLÓN 114 514,7 22.832 200 22,5 22,6 CASTROPOL 24 39,1 3.807 159 10,3 10,6 COAÑA 26 37,8 3.464 133 10,9 12,6 COLUNGA 35 49,6 3.778 108 13,1 13,0 CORVERA 93 307,0 16.109 173 19,1 19,6 CUDILLERO 35 69,1 5.763 165 12,0 12,7 Recogida selectiva total RECOGIDA SELECTIVA ENERO-DICIEMBRE 2011 PRINCIPADO DE ASTURIAS RESIDUO : PAPEL AÑO 2011 AÑO 2010 Nª TOTAL Nº HABITANTES/ MUNICIPIO PESO TOTAL (t) Nº HABITANTES kg/HABITANTE kg/HABITANTE CONTENEDORES CONTENEDOR DEGAÑA 12 9,2 1.223 102 7,5 6,2 EL FRANCO 20 47,7 4.046 202 11,8 11,9 GIJÓN 1.496 9.500,5 277.198 185 34,3 37,3 GOZÓN 56 181,6 10.788 193 16,8 17,2 GRADO 42 118,8 11.003 262 10,8 12,7 GRANDAS SALIME 11 11,5 1.036 94 11,1 9,9 IBIAS 8 4,6 1.698 212 2,7 3,1 ILLANO 2 1,4 465 233 3,1 3,4 ILLAS 7 12,1 1.004 143 12,1 10,4 LANGREO 235 820,8 45.397 193 18,1 19,0 LAVIANA -

The Columbus Chapel and Boal Mansion Museum in Boalsburg: a Must-See Destination for History Lovers

01 July | History, Museums, Susquehanna Region | Jim Cheney THE COLUMBUS CHAPEL AND BOAL MANSION MUSEUM IN BOALSBURG: A MUST-SEE DESTINATION FOR HISTORY LOVERS Share this with your friends! 1 0 Boal Mansion Museum Bottom Line: One of my top finds in Pennsylvania. A must-visit for history lovers. Cost: Adults: $10, Kids: $6 Hours: Tues-Sun: 1:30p-5p May 1 – October 31 Website: BoalMuseum.com Location: Address: 300 Old Boalsburg Road Boalsburg PA 16827 Every once in a while, I visit somewhere that’s so amazingly special that I can’t wait to share it with you: The Columbus Chapel and Boal Mansion Museum in Boalsburg is one of those places. Pulling up to this old home, I didn’t exactly know what to expect. My research had yielded connections to Christopher Columbus, Napoleon, and even Saint Bernard (of canine fame), but was it all a hoax? Surely there couldn’t be connections to those historic names in this small Pennsylvania borough. However, what I uncovered was one of the most amazing sites in all of Pennsylvania, and I was honored to have been invited to visit such an amazing place. The museum’s property includes a large mansion, several outbuildings, and a small, rustic chapel. The home was started as a basic log home, built in the first decade of the 19th century by one of the area’s first resident’s, David Boal. All told, eight generations of Boals lived in the home. David Boal’s son, George Boal, was very influential in the area, serving as a Representative in the Pennsylvania House and the founder of the Centre County Agricultural Society. -

Boletín Oficial Del Principado De Asturias

BOLETÍN OFICIAL DEL PRINCIPADO DE ASTURIAS NÚM. 278 DE 1-XII-2017 1/6 I. Principado de Asturias • ANUNCIOS CONSEJERÍA DE DESARROLLO RURAL Y RECURSOS NATURALES INFORMACIÓN pública sobre ayudas convocadas para el apoyo a las inversiones en explotaciones agrarias (Boletín Oficial del Principado de Asturias número 134, de 10 de junio de 2016). En cumplimiento de lo establecido en el artículo 18 de la Ley 38/2003, de 17 de noviembre, General de Subvenciones y en el Reglamento de Ejecución (UE) n.º 908/2014 de la Comisión de 6 de marzo de 2014 por el que se establecen disposiciones de aplicación del Reglamento (UE) n.º 1306/2013 del Parlamento Europeo y del Consejo en relación con los organismos pagadores y otros organismos, la gestión financiera, la liquidación de cuentas, las normas relativas a los controles, las garantías y la transparencia, se relacionan en anexo aquellas que han sido concedidas por la Consejería de Desarrollo Rural y Recursos Naturales, durante el ejercicio 2017, mediante convocatoria efectuada por Resolución de 1 de junio de 2016, con un crédito de 16.600.000,00 euros, con cargo a la aplicación presupuestaria 19.02.712F- 773.007. Lo que se hace público para su general conocimiento. En Oviedo, a 27 de noviembre de 2017.—El Secretario General Técnico.—Cód. 2017-13362. Anexo MEDIDA 04: INVERSIONES EN ACTIVOS FÍSICOS SUBMEDIDA 4.1: APOYO A LAS INVERSIONES EN EXPLOTACIONES AGRARIAS Nombre Código Postal Municipio residencia Ayuda total (€) JORGE SOL ARBAS 33815 ALLANDE 19.000,00 GANADERIA CARRAPUTEIRO SC 33880 ALLANDE 20.671,24 RAUL CONDE MESA 33887 ALLANDE 9.431,11 JOSE MANUEL PULIDO LOPEZ 33887 ALLANDE 11.071,08 GANADERIA FONTETA ALLANDE 33887 ALLANDE 120.745,00 LA MARGARITA S C. -

Provincia De OVIED O

204 -- Provincia de OVIED O Comprende esta provincia los siguientes ayuntamientos por partidos judiciales: Partido de Avilés. lilas. Avilés . Corvera de Asturias . Gozón . Castrillón . Soto del Barco. Partido de Belmonte. Miranda . Somiedo . Teverga . Salas. Partido de Cangas de Narcea . Cangas de Narcea . Degaña . Partido de Cangas de Onís. Ponga . Amieva Onís . Barres. Cangas de Onís. Ribadesella . Partido de Castropol . Tapia de Casariego . Boal Grandas de Salime. San Martín de Oscos . Tara unndi . Castropol . lllano . Santa Eulalia de Oscos . Vega den . Coaña. Pesoz_ . San Tirso de Abres. Franco (El) . Villanueva de Oscos . Partidos (dos) de Gijón . Carreño . Gijón . Partido de Infiesto. Cabranes . Nava. Piloiia . Partido de Laviana. Caso . Liviana . San Martín del Rey Aurelio . Sobrescobio . Langreo . Partido de Lena. Aller. 1 era . Quirós . Riosa. Partido de Luarca . Luarca . Navia . Villayón . Provincia de OVIEDO Tomo I. Resultados definitivos Fondo documental del Instituto Nacional de Estadística 1/4 - 205 - Partido de Llanes. Cabrales . Peñamellera Alta . Peñamellera Baja . Ribadedeva . Llanes . Partido de Mieres. Mieres. Morcín . Partido de Oviedo. Llanera . Ribera de arriba. 'roana . I Regueras (Las). OVIED O Santo Adriano. Partido de Pravia. Candamo. Grado . Muros de Nalón . Pravia . Cudillero. Partido de Siero. Bimenes. Noreña. Sariego. Siero. Partido de Tineo. Allande. Tineo . Partido de Villaviciosa. Carávia . Colunga . Villaviciosa . TOTAL DE LA PROVINCIA Partidos judiciales 18 Ayuntamientos 78 Provincia de OVIEDO Tomo I. Resultados definitivos Fondo documental del Instituto Nacional de Estadística 2/4 — 206 -- CENSO DE LA POBLACIÓN DE 1930 PROVINCIA DE OVIED O RESIDE 4TE S 0153) 11+2 ) (3 ) TOTAL , TOTA L (1) (2 ) TRANSEUN'lRS de la de l a PRESENTES AUSENTE S población 1 població n de d e Var . -

Resumen De Los Indicadores Utilizados

OBSERVATORIO DE SALUD EN ASTURIAS Tabla Resumen de Rankings por resultados y determinantes: Proyecto de Rankings, 2018 1 POSICION RESULTADOS DETERMINANTES POSICION 1 Caravia Illano / Eilao 1 2 Sobrescobio / Sobrescobiu San Martín de Oscos / Samartín de Oscos 2 3 Boal Yernes y Tameza 3 4 Coaña Santo Adriano 4 5 Taramundi Allande 5 6 Somiedo Taramundi 6 7 San Tirso de Abres / Santiso de Abres Degaña 7 8 Castropol Belmonte de Miranda / Miranda 8 9 Lena / Llena Villanueva de Oscos / Vilanova de Oscos 9 10 Castrillón Quirós 10 11 Navia Sariego / Sariegu 11 12 Corvera Ponga 12 13 Valdés Aller / Ayer 13 14 Santa Eulalia de Oscos / Santalla de Oscos Ibias 14 15 Tapia de Casariego / Tapia Coaña 15 16 Ribadedeva / Ribadeva San Tirso de Abres / Santiso de Abres 16 17 Franco, El Grandas de Salime 17 18 Villayón Castropol 18 19 Yernes y Tameza Peñamellera Alta 19 20 Caso / Casu Tineo / Tinéu 20 21 Colunga Candamo 21 22 San Martín de Oscos / Samartín de Oscos Teverga / Teberga 22 23 Aller / Ayer Franco, El 23 24 Oviedo / Uviéu Navia 24 25 Teverga / Teberga Regueras, Las / Regueres, Les 25 26 Avilés Castrillón 26 27 Llanes Cabranes 27 28 Vegadeo / Veiga, A Llanera 28 29 Villanueva de Oscos / Vilanova de Oscos Proaza 29 30 Mieres Somiedo 30 31 Riosa Pesoz / Pezós 31 32 Cudillero / Cuideiru Lena / Llena 32 33 Tineo / Tinéu Vegadeo / Veiga, A 33 34 Degaña Tapia de Casariego / Tapia 34 35 Sariego / Sariegu Noreña 35 36 Laviana / Llaviana Morcín 36 37 Gijón / Xixón Cabrales 37 38 Regueras, Las / Regueres, Les Ribadedeva / Ribadeva 38 39 Villaviciosa Riosa 39 40 Grandas de Salime Mieres 40 41 Carreño Onís 41 42 Proaza Bimenes 42 43 Cangas del Narcea Soto del Barco / Sotu'l Barcu 43 44 Langreo / Llangréu Nava 44 45 Pravia Parres 45 46 Salas San Martín del Rey Aurelio / S. -

Museo Castro De Chao Samartín Grandas De Salime, Asturias Catalogue

Museo Castro de Chao Samartín Grandas de Salime, Asturias Catalogue English version of the texts by Antonio García Álvarez and Eva González Busch Museo Castro de Chao Samartín / 537 Institutional presentations other sites in the region, such as Os Castros, of the Navia Basin Archaeological Director Plan. in Taramundi, or Monte Castrelo, in Pelóu. It By means of this document the Ministry for Mr Vicente Álvarez Areces is an essential collection in order to know the Culture and Tourism arranges and coordinates all President of the Principality of Asturias history of the first inhabitants of the region its archaeological interventions in the Navia-Eo and get closer to the numerous places of territory. Its results are already obvious on the It is with a deep democratic conception of culture cultural and tourist interest in the evocative ground; now we must strive to make them that the Government of the Principality of Asturias territory of the Navia and Porcía basins. well-known so that their diffusion benefits promotes archaeological works as a necessary our whole society. This is the final aim of this meeting point for research, processing, preservation In this significant Catalogue we present the book we are contentedly presenting today and diffusion of our archaeological and cultural extraordinary wealth of Chao Samartín and its in the conviction that proper dissemination heritage which is not always properly valued. Museum, genuine sample of our valuable cultural can only exist through rigorous work and heritage, ready for everyone’s enjoyment. sufficiently contrasted scientific discourse. The works promoted for the excavation of archaeological sites, research and conservation of cave art, fortified enclosures and other testimonies from the past, have favoured their Ms Mercedes Álvarez González Prologue recognition within the scientific field as well as Minister for Culture and Tourism Miguel Ángel de Blas Cortina the recent incorporation of five caves to the World of the Principality of Asturias Professor of Prehistory Heritage. -

Centros Municipales De Servicios Sociales

CENTROS MUNICIPALES DE SERVICIOS SOCIALES ÁREA I CENTROS M. SERVICIOS DIRECCIÓN SOCIALES MSS DE VEGADEO - Plaza del Ayuntamiento, s/n CASTROPOL- LOS OSCOS 33770 – VEGADEO Tfno.: 985 47 61 48 - VEGADEO Fax: 985 47 61 48 - TARAMUNDI [email protected] - SAN TIRSO DE ABRES Ayuntamiento de Castropol, Plaza Ayuntamiento, s/n - CASTROPOL 33760 – CASTROPOL Tfno.: 985/63 53 87 Fax: 985/ 63 50 58 [email protected] Plaza de Sargadelos - STA. EULALIA DE OSCOS 33776 – Sta. Eulalia de Oscos - SAN MARTIN DE OSCOS Tfno.: 985/ 62 60 32 - VILLANUEVA DE OSCOS Fax: 985/ 62 60 78 [email protected] C.M.S.S. DE BOAL – Plaza del Ayuntamiento, s/n GRANDAS DE SALIME 33720 – BOAL Tfno.: 985/ 62 02 40 - BOAL Fax: 985/62 01 78 - ILLANO [email protected] - GRANDAS DE SALIME Plza. de la Constitución, 1 - PESOZ 33730 – Grandas de Salime Tfno.: 985/62 75 65 Fax: 985/ 62 75 64 [email protected] C.M.S.S. EL FRANCO Plaza de España, s/n - EL FRANCO 33750 La Caridad – El Franco - TAPIA DE CASARIEGO Tfno.: 985/47 87 28 Fax: 985/47 87 28 [email protected] C.M.S.S. NAVIA Antonio Fdez. Vallina, 6–1º.Izda. - NAVIA 33710 – Navia - VILLAYÓN Tfno:985/47 33 00 - COAÑA Fax: 985/47 36 33 [email protected] C.M.S.S. VALDÉS Barrio Nuevo, 14 - LUARCA 33700 – LUARCA - TREVIAS Tfno.: 985/47 01 76 Fax: 985/ 47 03 71 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] 1 ÁREA II C.M.S.S. -

Asturias, Principado De

DIRECCIÓN GENERAL DE VIVIENDA Y SUELO Asturias, Principado de CÓDIGO POBLACIÓN TIPO FIGURA AÑO PUBLIC. PROVINCIA INE MUNICIPIO 2020 PLANEAMIENTO APROBACIÓN Asturias 33001 Allande 1.615 Plan General 2015 Asturias 33002 Aller 10.413 Plan General 2004 Asturias 33003 Amieva 628 Plan General 2006 Asturias 33004 Avilés 77.791 Plan General 2006 Asturias 33005 Belmonte de Miranda 1.437 Normas Subsidiarias 2001 Asturias 33006 Bimenes 1.679 Plan General 2011 Asturias 33007 Boal 1.482 Normas Subsidiarias 2003 Asturias 33008 Cabrales 1.941 Normas Subsidiarias 2003 Asturias 33009 Cabranes 1.057 Plan General 2020 Asturias 33010 Candamo 1.969 Plan General 2008 Asturias 33012 Cangas de Onís 6.209 Plan General 2004 Asturias 33011 Cangas del Narcea 12.124 Normas Subsidiarias 2003 Asturias 33013 Caravia 469 Plan General 2009 Asturias 33014 Carreño 10.301 Plan General 2014 Asturias 33015 Caso 1.457 Plan General 2010 Asturias 33016 Castrillón 22.273 Plan General 2001 Asturias 33017 Castropol 3.342 Plan General 2006 Asturias 33018 Coaña 3.296 Normas Subsidiarias 2003 Asturias 33019 Colunga 3.205 Normas Subsidiarias 1999 Asturias 33020 Corvera de Asturias 15.525 Plan General 2015 Asturias 33021 Cudillero 4.922 Normas Subsidiarias 2004 Asturias 33022 Degaña 881 Normas Subsidiarias 1996 Asturias 33023 Franco, El 3.760 Plan General 2009 Asturias 33024 Gijón 271.717 Plan General 2019 Asturias 33025 Gozón 10.282 Plan General 2015 Asturias 33026 Grado 9.703 Plan General 2012 Asturias 33027 Grandas de Salime 815 Plan General 2006 Asturias 33028 Ibias 1.207 Normas -

1 Barranquismo Riofrío- Valle Del Navia. Serandinas. Boal. Asturias 1

BARRANQUISMO RIOFRÍO - VALLE DEL NAVIA. SERANDINAS. BOAL. ASTURIAS El barranquismo en el Riofrío se desarrolla en el entorno del Valle del río Navia, muy cerca de Serandinas. Estamos en una comarca pizarrosa, con intervalos de cuarcita, por dónde el agua erosiona su cauce creando formas caprichosas dando lugar a rincones increíbles con diferentes obstáculos naturales. Durante el recorrido por este barranco, el agua nos ayuda a progresar caminando por el propio cauce del rio, para ello tendremos que efectuar saltos a pozas, nadar y descender por diferentes cascadas utilizando cuerdas, mosquetones y rapeladores. De esta forma, podremos superar con mayor seguridad estas dificultades técnicas que se nos van presentando. Para mayor seguridad, iremos guiados y supervisados por guías profesionales. Esta actividad discurre por un escenario de difícil acceso, la mejor manera para conocer este entorno es haciendo barranquismo. Este emocionante deporte, tiene un elevado componente de aventura, se trata de un continuo reto que pone al descubierto nuevas técnicas de progresión y, todo ello, en un entorno natural privilegiado que muy pocas personas tienen el gusto de conocer y disfrutar… 1.- LUGAR. ZONA Valle del Navia. Entorno Serandinas - Boal. DISTANCIAS (KM) 18 km Navia - 36 km Tapia de Casariego - 40 km Luarca - 69 km Ribadeo - 73 km Oviedo - 120 km Gijón - 160 Lugo - 196 km Coruña - 204 km Llanes - 235 km Santiago de Compostela - 252 km León - 291 km Santander - 380 km Bilbao 2.- HORARIOS. DURACIÓN 4 H 30 MIN - 5 H aprox. El cómputo del tiempo se refiere a la recepción: explicación, toma de datos, proporcionar equipo y vestirse (30 minutos aprox) + desplazamiento en furgoneta (8 minutos) + aproximación caminando (8-10 minutos) + Descenso de barranco (3-4 H) + salida hasta coger vehículo (20 minutos) + cambiarse y duchas (20 minutos). -

Aller Boal Boal Cangas Del Narcea Cangas Del Narcea Cangas Del Narcea I Cangas Del

~ - -- ~ ~ - -- 4436 BOLETIN OFIQAL DEL PRINCIPADO DE ASTURIAS Y DE LA PROVINCIA 29-VIII-90 resuelve conceder subvenciones para la restauracion REStJELVO: de molinos y OlrOS ingenios hidraulicos. Primero.-Convocar concurso para la adjudicaci6n de Vistos los informes sobre los distintoJ expedientes, pre una beca de investigaci6n en el area de conocimiento que en sentados por el Servicio de Patrimonio Historico, y en virtud el apartado siguiente se especifica . de 10dispuesto en la Ley 6/84, de 5 de julio , del Presidente y del Consejo de Gobiemo del Principado de Asturias, el Segundo.-Aprobar las bases que a continuaci6n se deter Decreto 78/83, de 27 de octubre, por el que se establece el minan y que habran de regir el concurso de referencia. regimen general de concesi6n de subvenciones y la Resolu ci6n de esta Consejeria de 14 de febrero de 1990, regulando l.-Dbjeto: Es objeto de la pre sente convocatoria la con el sistema de concesi6n de subvenciones para la restauraci6n cesi6n de una beca de formaci6n de la Consejeria de Sanidad de molinos y otros ingenios hidraulicos, y Servicios Sociales : Por la presente, Centro Area N.O de becas RESUELVO : Hospital . Screening de Monte Naranco cancer de mama 1 Primero.-Conceder subvenciones para la restauraci6n de molinos y otros ingenios hidraulicos, con cargo a la partida La beca tiene por objeto participar en el programa piloto presupuestaria 15-02-458D-782, a los solicitantes y en las de screening de cancer de mama como 2.° lector de mamogra cuantias que a continuaci6n se expresan: ffas a fin de investigar el grado de acuerdo entre lectores.