Panopticon from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

150 Year Gold Timeline (1829 – 1970'S) Teacher Resource

150 Year Gold Timeline (1829 – 1970’s) Teacher Resource The following timeline is a summary of information from the Heart of Gold Australia app, plus other key dates, ordered chronologically for your reference. Year Person/Organisation Event Importance 1829 British Government Arrival of the First Start of Swan Fleet River Colony 1836 Governor James Old Court House built A place where Stirling and engineer criminal and civil Henry Willey Reveley cases were heard to help keep peace in the colony 1856 Queen Victoria Proclaimed Perth as a Governed by its city own council 1876 Sir Charles ‘Scruffy’ Moved from London Supplied gold McNess to Perth prospecting equipment and later helped developed Perth city 1885 Charlie Hall Finds 870g nugget in Contestable first Halls Creek noteworthy gold find in state 1890-1895 Sir William Cleaver Appointed by British Selected John Francis Robinson Government as Forrest as Governor of Western Premer of Australia Western Australia 1890 John Forrest Becomes Premier of The first premier (1890-1901) Western Australia of WA Keen to address colony’s urgent needs including harbour, pipeline and railway for gold industry 1892 Arthur Bayley and Carries 540ounces First noteworthy William Ford (over 15kg) of gold gold find in the to Southern Cross state, Fly Flat Bank Coolgardie 1892 Paddy Hannan Discovers gold 40km Named “The east of Coolgardie Golden Mile” which later becomes Kalgoorlie Gold Rush starts The #heartofgold Discovery Trail is a community initiative of the Gold Industry Group P: +61 8 6314 6333 E: [email protected] W: goldindustrygroup.com.au 1892 Clara Saunders Arrived in WA Nursing miners Goldfields who were sick with dysentery 1892 Government Passed law Married women could own property and therefore mining leases etc. -

Newly Refurbished, the Pen Draws Crowds Airbnb Study Shows Growth Across WA Backpacker Tax Relief to Drive Visitation

OSPITALITY WA The Magazine of the Australian Hotels Association (WA). October/November 2016 - Issue 55 Newly Refurbished, The Pen Draws Crowds Airbnb Study Shows Growth Across WA Backpacker Tax Relief to Drive Visitation Corporate Corporate Corporate Corporate Corporate Sponsor Sponsor Sponsor Sponsor Sponsor You’re with the Super Fund of the Year. That’s a plus. We’re proud to be recognised as Rainmaker SelectingSuper’s Super Fund of the Year for the second consecutive year. Our consistent investment performance*, low fees and competitive insurance ensures you retire with more. And that’s a plus. hostplus.com.au Issued by Host-Plus Pty. Limited ABN 79 008 634 704, RSEL No. L0000093 AFSL No. 244392 as trustee for the Hostplus Superannuation Fund ABN 68 657 495 890 RSE No. R1000054, MySuper No. 68657495890198, which includes the Hostplus Pension. This information is general in nature and is not intended to be a substitute for professional financial product advice. You should determine the appropriateness of the information having regard to your objectives, financial situation and needs, and obtain and consider a copy of the Product Disclosure Statement before making an investment decision. Ratings are only one factor to be taken into account when deciding whether to acquire, continue to hold or dispose of a financial product. *Rainmaker SelectingSuper June 2015 Survey. HOST8975_SS_AHA_WA HOST8975 Selecting Super 210x297_AHA_WA.indd 1 5/09/2016 1:38 pm 5 7 You’re with the Super Fund 16 12 10 of the Year. contents GENERAL NEWS EVENT NEWS VENUE NEWS That’s a plus. 5 Fight Over Price Parity Continues 12 WA Shines on National Awards 20 Revamped Peninsula Bar and 23 WA Bartenders are Helping People Stage Restaurant Focuses on High Diagnosed with Leukaemia 13 Hospitality Awards for Excellence Standard of Service, Food and Drink We’re proud to be recognised as Rainmaker SelectingSuper’s Super Fund 26 Online Reviews and Endorsements Tickets on Sale 24 The Reveley Reveals an Array of Under Review Food and Beverage at a Prime of the Year for the second consecutive year. -

Short-Term Custodial Design Is Outdated

School of Built Environment Short-term custodial design is outdated: developing knowledge and initiatives for future research and a specialised strategic architecture for Police Custodial Facilities. Emil Jonescu This thesis is presented for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy of Curtin University September 2013 Declaration: To the best of my knowledge and belief this thesis contains no material previously published by any other person except where due acknowledgment has been made. This thesis contains no material which has been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma in any university. Acknowledgements I would like to thank my supervisors for their expertise, tutelage, guidance and inspiration throughout the preparation of this thesis. I attribute this result in part to their encouragement. A special mention must be made of the administrative support given by members of Humanities staff and to all of the sworn, un-sworn, retired and previous members of the Western Australia Police (henceforth WA Police) who gave up their time to make this research possible, and in particular to staff of the WA Police Academic Research Administration Unit for their support. Finally, I thank my wife and family for their patience and support, for it is they who also sacrifice and have by default undertaken this research. i Content Index Preliminaries Page Title page Acknowledgements i List of Figures iii Definitions iv Timeline of penal events vii Abstract 1 Introduction 2 Chapter 1. History of Punishment and WA Policing 19 2. Architectural Response: WA Prison Facilities 62 3. Architectural Response: Police Custodial Facilities 75 4. Case Study: Questionnaire, Site Analysis and Fieldwork Methodology 86 5. -

Street Names Index

City of Fremantle and Town of East Fremantle Street Names Index For more information please visit the Fremantle City Library History Centre Place Name Suburb Named After See Also Notes Ada Street South Fremantle Adams Street O'Connor The Adcock brothers lived on Solomon Street, Fremantle. They were both privates in the 11 th Frank Henry Burton Adcock ( - Battalion of the AIF during WWI. Frank and Adcock Way Fremantle 1915) and Fredrick Brenchley Frederick were both killed in action at the Adcock ( - 1915) landing at Gallipoli on the 25 th of April 1915, aged 21 and 24 years. Adelaide of Saxe-Meiningen, queen Adelaide Street Fremantle consort of King William IV (1830- Appears in the survey of 1833. 1837). Agnes Street Fremantle Ainslie Road North Fremantle Alcester Road East Fremantle Alcester, England Alexander was Mayor of the Municipality of Wray Avenue Fremantle, 1901-02. Alexander Road Fremantle Lawrence Alexander and Hampton Originally Hampton Street until 1901-02, then Street named Alexander Road, and renamed Wray Avenue in 1923 after W.E. Wray. Alexandra of Denmark, queen Queen Alexandra was very popular throughout Alexandra Road East Fremantle consort of King Edward VII (1901- her time as queen consort and then queen 1910). mother. 1 © Fremantle City Library History Centre Pearse was one of the original land owners in Alice Avenue South Fremantle Alice Pearse that street. This street no longer exists; it previously ran north from Island Road. Alfred Road North Fremantle Allen was a civil engineer, architect, and politician. He served on the East Fremantle Municipal Council, 1903–1914 and 1915–1933, Allen Street East Fremantle Joseph Francis Allen (1869 – 1933) and was Mayor, 1909–1914 and 1931–1933. -

Wasfr News Spring 2015

WESTERN AUSTRALIA SELF FUNDED RETIREES INC. State and Federal Advocates for Fully and Partly Self Funded Retirees WASFR NEWS VOLUME 5 ISSUE 1 SPRING 2015 WASFR PRE-CHRISTMAS INSIDE THIS ISSUE: GET TOGETHER Our next meeting on 13 NOVEMBER will be the last for the year. Everyone is invited PRESIDENT’S 1-3 to come along and enjoy some Christmas Cheer and catch up with fellow members. REPORT There will be no Guest Speaker. EDITORIAL 3 Do not bring anything other than your happy selves. Everything that is required for a good time will be provided. GUEST SPEAKERS 4-11 Our normal meetings will resume on 12 February 2016. FUTURE SPEAKERS 12 Our President Ron will not be with us on the 13th, and he takes this opportunity to wish AND CREDITS all members and their families a Merry Christmas and a bright and prosperous New Year. PRESIDENT’S REPORT Now that winter seems to have passed, we can start to enjoy those beautiful sum- mer evenings and the longer days that go with this time of the year. I do prefer summer to winter! (Your Editor does not agree!) At our age, we know that we live in an ever-changing world and that we should never get complacent—ask Tony Abbott. The change of Prime Minister to Mal- colm Turnbull was not a surprise; in fact, some even thought that it might have happened earlier this year. It is still too early to cast judgement on whether this is a good move. However, it does seem that there may be scope for us to feel a little more optimistic. -

180Th Year Celebration of the Old Courthouse Launch of the Final

180th Year Celebration of the Old Courthouse and Launch of the Final Stage of Redesign of the Law Museum Address by The Honourable Wayne Martin AC Chief Justice of Western Australia 23 March 2017 Attorney General of Western Australia, the Honourable John Quigley MLA, President of the Law Society of Western Australia Mr Alain Musikanth, distinguished guests too numerous to mention, ladies and gentlemen. I am greatly honoured to have been invited to address this gathering to celebrate the 180th anniversary of the opening of the building which now houses the Francis Burt Law Education Programme, and the Law Museum, and to formally launch the final stage of the redesign of the Museum. Before going any further I would like to thank Aunty Marie Taylor for her characteristically generous welcome to country, and pay my respects to the Elders past and present of the traditional owners of the lands on which we meet, the Whadjuck people who form part of the great Nyoongar Clan of South Western Australia, and acknowledge their continuing stewardship of these lands. The 1837 Building The building we celebrate this evening is the oldest building still standing in the City of Perth. It was designed by Henry Willey Reveley, who also designed the oldest building in the metropolitan area - the Round House at Fremantle, which was built in 1831, just two years after the Colony was founded. The Honourable Nick Hasluck AM QC, who regrettably cannot be with us this evening, wrote of Reveley's interesting life, including his association with Percy Bysshe Shelley and his opportunistic joinder of Captain Stirling's ships as they called in at Cape Town on their way to the Swan River Settlement, just after he had been dismissed from his then position, in a fascinating article published in this month's edition of Brief magazine. -

Experience a of Living

FREE MONTHLY Established 1991 PRINT POST APPROVED: 64383/00006 SUPPORTING SENIORS’ RECREATION COUNCIL OF WA (INC) on Wednesday 25 March - OPEN HOUSE see page 2 EXPERIENCE ANew WayOF LIVING In our lifetimes there are few times we can enjoy the freedom to do what we choose. Perhaps as a young child playing in the sandpit or scribbling with crayons on a sheet of paper we have the opportunity to freely express ourselves. From there we have the regimentation of schooling, starting work, buying a home, raising kids, paying off mortgages, whatever, until we reach the mature age of 55 years and onwards. After this time we have the opportunity to reassess the way we live. Children have left the family home which may have now become a little too big and require more of your time to maintain or the idea of a new home with all the latest design features and appliances might be a more appealing option. With this lessening responsibility you now have a real chance to choose what YOU want. Call 1300 055 055 or Kathleen on 0408 516 840 | www.belswan.com.au Come and see us now at Lovegrove Street, Pinjarra – opposite the Bowling Club A Bus to Go NEW HOME At Belswan Pinjarra the residents are not just physically active they are socially active, always NEW LIFE ready for a social outing and they have just the bus to do The residents of Belswan’s Pinjarra Lifestyle it. Whether they are off to Village understand this statement because they a restaurant, a concert or a road trip to some area of are indeed living their new life. -

Early New Norcia

No. 168 July 2020 Our July 2020 meeting Bob Reece Early New Norcia Tuesday 14 July 2020 at 5.00pm for 5.30pm in the Great Southern Room 4th floor, State Library of Western Australia. Please see details1 on page 3. Objectives The objectives of the Friends of Battye Library (Inc.) are to assist and promote the interests of the JS Battye Library of West Australian History and the State Records Office, and of those activities of the Library Board of Western Australia concerned with the acquisition, preservation and use of archival and documentary materials. Patron Mrs Ruth Reid AM Committee (2019-2020) President Pamela Statham Drew Vice President Jennie Carter, Secretary Heather Campbell Treasurer Nick Drew Membership Sec. Cherie Strickland Committee members Shirley Babis, Kris Bizacca, Lorraine Clarke, Steve Errington, Neil Foley, Robert O’Connor QC Richard Offen (Co-opted), and Gillian O’Mara. Ex-Officio Margaret Allen (CEO & State Librarian) Damian Shepherd (CEO State Records Office) Kate Gregory (Battye Historian) Newsletter editor Jennie Carter Volunteers Ring (08) 9427 3266 or email: [email protected] All correspondence to: The Secretary, PO Box 216, Northbridge WA 6865. ISSN 1035-8692 Views expressed in this newsletter are not necessarily those of the Friends of Battye Library Committee, the State Library of Western Australia, or the State Records Office. 2 July Meeting To be held on Tuesday 14 July 2020 in the Great Southern Room, fourth floor State Library of Western Australia at 5pm for 5.30pm Dr Bob Reece Early New Norcia the 1867 photographs of WW Thwaites Details of Bob’s talk are on page 4 After the meeting, members are very welcome to join us for a meal at a nearby Perth restaurant. -

Draft Heritage Assessment Which Includes Statement of Significance

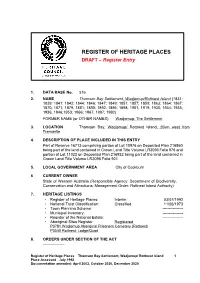

REGISTER OF HERITAGE PLACES DRAFT – Register Entry 1. DATA BASE No. 516 2. NAME Thomson Bay Settlement, Wadjemup/Rottnest Island (1831; 1839; 1841; 1842; 1844; 1846; 1847; 1849; 1851; 1857; 1859; 1863; 1864; 1867; 1870; 1871; 1879; 1881; 1890; 1892; 1895; 1898; 1901; 1919; 1930; 1934; 1935; 1936; 1946;1953; 1966; 1967; 1987; 1992) FORMER NAME (or OTHER NAMES) Wadjemup; The Settlement 3. LOCATION Thomson Bay, Wadjemup/ Rottnest Island, 20km west from Fremantle 4. DESCRIPTION OF PLACE INCLUDED IN THIS ENTRY Part of Reserve 16713 comprising portion of Lot 10976 on Deposited Plan 216860 being part of the land contained in Crown Land Title Volume LR3096 Folio 976 and portion of Lot 11022 on Deposited Plan 216932 being part of the land contained in Crown Land Title Volume LR3096 Folio 921. 5. LOCAL GOVERNMENT AREA City of Cockburn 6 CURRENT OWNER State of Western Australia (Responsible Agency: Department of Biodiversity, Conservation and Attractions; Management Order: Rottnest Island Authority) 7. HERITAGE LISTINGS • Register of Heritage Places: Interim 03/07/1992 • National Trust Classification: Classified 11/06/1973 • Town Planning Scheme: ---------------- • Municipal Inventory: ---------------- • Register of the National Estate: ---------------- • Aboriginal Sites Register Registered P3781 Wadjemup Aboriginal Prisoners Cemetery (Rottnest) P3540 Rottnest: Lodge/Quod 8. ORDERS UNDER SECTION OF THE ACT ----------------- Register of Heritage Places Thomson Bay Settlement, Wadjemup/ Rottnest Island 1 Place Assessed July 1992 Documentation amended: -

REGISTER of HERITAGE PLACES Permanent Entry

REGISTER OF HERITAGE PLACES Permanent Entry HERITAGE COUNCIL OF WESTERN AUSTRALIA 1. Data Base No. 0896 2. Name. Round House, and Arthur Head Reserve (1830-31) 3. Description of elements included in this entry. Arthur Head Reserve, including the Round House and the Kerosene Store, being Reserve 21563. 4. Local Government Area. City of Fremantle 5. Location. Western end of High Street, Fremantle 6. Owner. Vested in the City of Fremantle 7. Statement of Significance of Place (Assessment in Detail) DOCUMENTARY EVIDENCE The Round House was constructed in 1830-31, almost immediately upon the settlement of the Swan River Colony, not so much to house local criminals, but unruly strangers to the port and the drunks amongst the less hopeful of arrivals.1 The Round House was designed by Henry Willey Reveley, an architect and engineer, who had accepted the position of Civil Engineer to the Colony.2 Reveley was involved with the design of all of the early public buildings in the colony, including the Round House, Government Offices, Commissariat Stores, Courthouse and the first Government House. The building is twelve sided and self-contained. All rooms face an inner courtyard, which provides for light and ventilation, and was used as an exercise yard. The design was based on Bentham's panopticon,3 and thus embodied the latest design principles of incarcerative architecture at the time.4 However the built version was scaled down from the preliminary sketches.5 After some debate on the relative merits of the building of the cliff or on the flats, the Arthur's head site was chosen and tenders were called, in July 1830. -

Michael Mccarthy, Nonja Peters & Sue Summers the Flying Boats Of

NO. 143 March 2012 ABN 571625138800 March 2012 Meeting Michael McCarthy, Nonja Peters & Sue Summers The flying boats of Roebuck Bay - March 1942. A Dutch crew from a visiting Dornier Do 24 flying boat in Roebuck Bay being taken into Broome by launch in 1941. [Australian War Memorial collection No. 044613] To be held on Tuesday 13 March 2012 at 5.00pm for 5.30pm in the Great Southern Room, 4th floor State Library of Western Australia. Please see details on Page 3 Objectives The objectives of the Friends of Battye Library (Inc.) are to assist and pro- mote the interests of the J S Battye Library of West Australian History and the State Records Office, and of those activities of the Library Board of Western Australia concerned with the acquisition, preservation and use of archival and documentary materials. Patron Mrs Ruth Reid AM Emeritus President Professor Geoffrey Bolton AO Committee (2011-2012) President Dr Pamela Statham Drew Vice President Mrs Gillian O’Mara Secretary position vacant Treasurer Mr Nick Drew Committee members Mr Graham Bown, Ms Jennie Carter, Dr Alison Gregg, Mr Jim Gregg, Mr Robert O’Connor QC, Mr Lindsay Peet, Dr Nonja Peters, and Ms Sue Summers. Ex-Officio Mrs Margaret Allen (CEO & State Librarian) Ms Cathrin Cassarchis (State Archivist, SRO) Dr Sarah McQuade (Battye Historian) Newsletter editor Ms Jennie Carter Volunteers Ring (08) 9427 3266 or email: [email protected] All correspondence to: The Secretary, PO Box 216, Northbridge WA 6865 ISSN 1035-8692 Views expressed in this newsletter are not necessarily those of the Friends of Battye Library Committee, the State Library of WA, or the State Records Office. -

Christmas Greetings

FREMANTLE HISTORY SOCIETY Established 1994 The Secretary, PO Box 1305 FREMANTLE WA 6959 Spring Edition, 2013 Editors: Dianne Davidson, Anne Brake, Ron Davidson Patron: Dr Brad Pettitt, Mayor of Fremantle An 'early and important photographs' of Fremantle, by Stephen Montague Stout, convict., teacher, photographer and journalist, of William Pearse's butcher shop at the corner of High and Pakenham streets c1863. Fremantle City Library: Local History Collection: Fremantle Society Image no. 6.25 BUMPER CROWD AT 17TH FREMANTLE STUDIES Ron Davidson Fremantle Studies Day 2013 – our 17th - was a day when records were broken. Despite counter attractions like the Blessing of the Fleet and the Seafood Festival more than 100 people attended. Ninety-two were formally registered but there was a number of ‘extras’. The theme of ‘Images and Evidence of Early Fremantle Life’ was obviously attractive for the crowd which packed every seat in the lecture room in the Burt Street Artillery Barracks. There was a time 1 CHRISTMAS GREETINGS: come to our special lunch (see pg 3) when the Studies Day struggled to top an three weeks of the arrival of the first private audience of 20 or 30 participants. Now it is settlers on the Calista in August 5 1829 clearly part of public history. surveyor John Septimus Roe was laying out blocks in Fremantle and the first were The Studies Day began with Irma Walters’ allocated within a month. Houses, inns and paper on Stephen Montague Stout, an early shops began to appear. A post office, a teacher, photographer and convict who weekly handwritten newspaper, a burial made an art of self promotion.