Daniel Deronda

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Full Journal (PDF)

SAPIR A JOURNAL OF JEWISH CONVERSATIONS THE ISSUE ON POWER ELISA SPUNGEN BILDNER & ROBERT BILDNER RUTH CALDERON · MONA CHAREN MARK DUBOWITZ · DORE GOLD FELICIA HERMAN · BENNY MORRIS MICHAEL OREN · ANSHEL PFEFFER THANE ROSENBAUM · JONATHAN D. SARNA MEIR SOLOVEICHIK · BRET STEPHENS JEFF SWARTZ · RUTH R. WISSE Volume Two Summer 2021 And they saw the God of Israel: Under His feet there was the likeness of a pavement of sapphire, like the very sky for purity. — Exodus 24: 10 SAPIR Bret Stephens EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Mark Charendoff PUBLISHER Ariella Saperstein ASSO CIATE PUBLISHER Felicia Herman MANAGING EDITOR Katherine Messenger DESIGNER & ILLUSTRATOR Sapir, a Journal of Jewish Conversations. ISSN 2767-1712. 2021, Volume 2. Published by Maimonides Fund. Copyright ©2021 by Maimonides Fund. No part of this journal may be reproduced in any form or by any means without the prior written consent of Maimonides Fund. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. WWW.SAPIRJOURNAL.ORG WWW.MAIMONIDESFUND.ORG CONTENTS 6 Publisher’s Note | Mark Charendoff 90 MICHAEL OREN Trial and Triage in Washington 8 BRET STEPHENS The Necessity of Jewish Power 98 MONA CHAREN Between Hostile and Crazy: Jews and the Two Parties Power in Jewish Text & History 106 MARK DUBOWITZ How to Use Antisemitism Against Antisemites 20 RUTH R. WISSE The Allure of Powerlessness Power in Culture & Philanthropy 34 RUTH CALDERON King David and the Messiness of Power 116 JEFF SWARTZ Philanthropy Is Not Enough 46 RABBI MEIR Y. SOLOVEICHIK The Power of the Mob in an Unforgiving Age 124 ELISA SPUNGEN BILDNER & ROBERT BILDNER Power and Ethics in Jewish Philanthropy 56 ANSHEL PFEFFER The Use and Abuse of Jewish Power 134 JONATHAN D. -

Towards Decolonial Futures: New Media, Digital Infrastructures, and Imagined Geographies of Palestine

Towards Decolonial Futures: New Media, Digital Infrastructures, and Imagined Geographies of Palestine by Meryem Kamil A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (American Culture) in The University of Michigan 2019 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Evelyn Alsultany, Co-Chair Professor Lisa Nakamura, Co-Chair Assistant Professor Anna Watkins Fisher Professor Nadine Naber, University of Illinois, Chicago Meryem Kamil [email protected] ORCID iD: 0000-0003-2355-2839 © Meryem Kamil 2019 Acknowledgements This dissertation could not have been completed without the support and guidance of many, particularly my family and Kajol. The staff at the American Culture Department at the University of Michigan have also worked tirelessly to make sure I was funded, healthy, and happy, particularly Mary Freiman, Judith Gray, Marlene Moore, and Tammy Zill. My committee members Evelyn Alsultany, Anna Watkins Fisher, Nadine Naber, and Lisa Nakamura have provided the gentle but firm push to complete this project and succeed in academia while demonstrating a commitment to justice outside of the ivory tower. Various additional faculty have also provided kind words and care, including Charlotte Karem Albrecht, Irina Aristarkhova, Steph Berrey, William Calvo-Quiros, Amy Sara Carroll, Maria Cotera, Matthew Countryman, Manan Desai, Colin Gunckel, Silvia Lindtner, Richard Meisler, Victor Mendoza, Dahlia Petrus, and Matthew Stiffler. My cohort of Dominic Garzonio, Joseph Gaudet, Peggy Lee, Michael -

On Robert Alter's Bible

Barbara S. Burstin Pittsburgh's Jews and the Tree of Life JEWISH REVIEW OF BOOKS Volume 9, Number 4 Winter 2019 $10.45 On Robert Alter’s Bible Adele Berlin David Bentley Hart Shai Held Ronald Hendel Adam Kirsch Aviya Kushner Editor Abraham Socher BRANDEIS Senior Contributing Editor Allan Arkush UNIVERSITY PRESS Art Director Spinoza’s Challenge to Jewish Thought Betsy Klarfeld Writings on His Life, Philosophy, and Legacy Managing Editor Edited by Daniel B. Schwartz Amy Newman Smith “This collection of Jewish views on, and responses to, Spinoza over Web Editor the centuries is an extremely useful addition to the literature. That Rachel Scheinerman it has been edited by an expert on Spinoza’s legacy in the Jewish Editorial Assistant world only adds to its value.” Kate Elinsky Steven Nadler, University of Wisconsin March 2019 Editorial Board Robert Alter Shlomo Avineri Leora Batnitzky Ruth Gavison Moshe Halbertal Hillel Halkin Jon D. Levenson Anita Shapira Michael Walzer J. H.H. Weiler Ruth R. Wisse Steven J. Zipperstein Executive Director Eric Cohen Publisher Gil Press Chairman’s Council Blavatnik Family Foundation Publication Committee The Donigers of Not Bad for The Soul of the Stranger Marilyn and Michael Fedak Great Neck Delancey Street Reading God and Torah from A Mythologized Memoir The Rise of Billy Rose a Transgender Perspective Ahuva and Martin J. Gross Wendy Doniger Mark Cohen Joy Ladin Susan and Roger Hertog Roy J. Katzovicz “Walking through the snow to see “Comprehensive biography . “This heartfelt, difficult work will Wendy at the stately, gracious compelling story. Highly introduce Jews and other readers The Lauder Foundation– home of Rita and Lester Doniger recommended.” of the Torah to fresh, sensitive Leonard and Judy Lauder will forever remain in my memory.” Library Journal (starred review) approaches with room for broader Sandra Earl Mintz Francis Ford Coppola human dignity.” Tina and Steven Price Charitable Foundation Publishers Weekly (starred review) March 2019 Pamela and George Rohr Daniel Senor The Lost Library Jewish Legal Paul E. -

G. Robert Stange

Recent Studies in Nineteenth-Century English Literature G. ROBERT STANGE THE FIRST reaction of the surveyor of the year's work in the field of the nineteenth century is dismay at its sheer bulk. The period has obviouslybecome the most recent playground of scholars and academic critics. One gets a sense of settlers rushing toward a new frontier, and at 'times regrets irra- tionally ithe simpler, quieter days. At first glance the massive acocumulation of intellectual labor which I have undertaken to describe seems to display no pattern whatsoever, no evidence of noticeable trends. Yet, to the persistent gazer certain characteristics ultimately reveal themselves. There is a discernible tendency? for example, to lapply the concepts of po'st Existential theology to the work of the Romantic poets; and in general these poets are now being approached with an intellectual excitement which is very different from the diffuse "romantic" enthusiasm of twenty or thirty years ago. It must also be said that the Victorian novelists continue to come into 'their own. lThe kind of serious attention 'thiatit is now assumed Dickens and George Eliot require was a rare thing a decade ago; it is undoubtedly good that this rigorous- thiough sometimes over-solemn-analysis is now being extended to 'some of 'the lesser novelists of the period. It is also still to be noted as an unaccountable oddity th'at reliable editions of even the most important nineteenth-century authors are not always available. Of the novelists 'only Jane Austen has so far 'been critically edited. The Victorian poets, with the exception of Arnold, are in textual chaos, and ;though critical editions of Arnold's and Mill's prose are forthcoming, other prose writers have not 'been much heeded. -

Why Does Daniel Deronda's Mother Live in Russia? Catherine Brown

Why Does Daniel Deronda’s Mother Live In Russia? Catherine Brown Eliot, like Daniel, wanted to avoid “a merely English attitude in studies” (Daniel Deronda [DD] 155). She educated herself to a degree which her critics struggle to match about Germany, Spain, France, Italy, Bohemia, and Palestine -- but not about Russia. In her relative lack of interest in this country she was typical of her own country and time; Lewes’s acquaintance Laurence Oliphant noted in his 1854 account of his travels in Russia that “the scanty information which the public already possesses has been of such a nature as to create an indifference towards acquiring more” (vii). Apart from the works of Turgenev, Eliot is not known to have read any Russian literature, even though Gogol’, Dostoevskii, and Tolstoi would have been available to her in French translation. The take-off decade for English translations of Russian literature started in the year of her death (Brewster 173). Why, then, having hitherto mentioned the country in her fiction only as a source of linseed in The Mill on the Floss, did she choose Russia as the location of Leonora Alcharisi’s second marriage, self-imposed exile from singing and Europe, and emotional and physical decline? Of course, Russia is not simply imposed on Alcharisi by Eliot; she also chose it for herself (this article will treat her and her second husband as though they were real people, in the interests of historical investigation). After the death of her first husband she had suitors of many countries, including Sir Hugo Mallinger, and there is no reason to think that by the age of thirty her options had narrowed to a single man. -

The “Former Sun” in the Sidereal Clock: The

The “Former Sun” in the Sidereal Clock: The Kabbalistic Heavens and Time in The Spanish Gypsy and Daniel Deronda Author(s): Caroline Wilkinson Source: George Eliot - George Henry Lewes Studies, Vol. 68, No. 1 (2016), pp. 25-42 Published by: Penn State University Press Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5325/georelioghlstud.68.1.0025 Accessed: 16-09-2018 23:56 UTC JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at https://about.jstor.org/terms Penn State University Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to George Eliot - George Henry Lewes Studies This content downloaded from 73.121.242.252 on Sun, 16 Sep 2018 23:56:41 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms The “Former Sun” in the Sidereal Clock: The Kabbalistic Heavens and Time in The Spanish Gypsy and Daniel Deronda Caroline Wilkinson University of Tennessee In both her epic poem The Spanish Gypsy and her final novel Daniel Deronda, Eliot drew upon kabbalistic concepts of the heavens through the characters of Jewish mystics. In the later novel, Eliot moved the mystic, Mordecai, from the narrative’s periphery to its center. This change, symbolically equated within the novel to a shift from geocentricism to heliocentrism, affects time in Daniel Deronda both in terms of plot and historical focus. -

George Eliot on Stage and Screen

George Eliot on Stage and Screen MARGARET HARRIS* Certain Victorian novelists have a significant 'afterlife' in stage and screen adaptations of their work: the Brontes in numerous film versions of Charlotte's Jane Eyre and of Emily's Wuthering Heights, Dickens in Lionel Bart's musical Oliver!, or the Royal Shakespeare Company's Nicholas Nickleby-and so on.l Let me give a more detailed example. My interest in adaptations of Victorian novels dates from seeing Roman Polanski's film Tess of 1979. I learned in the course of work for a piece on this adaptation of Thomas Hardy's novel Tess of the D'Urbervilles of 1891 that there had been a number of stage adaptations, including one by Hardy himself which had a successful professional production in London in 1925, as well as amateur 'out of town' productions. In Hardy's lifetime (he died in 1928), there was an opera, produced at Covent Garden in 1909; and two film versions, in 1913 and 1924; together with others since.2 Here is an index to or benchmark of the variety and frequency of adaptations of another Victorian novelist than George Eliot. It is striking that George Eliot hardly has an 'afterlife' in such mediations. The question, 'why is this so?', is perplexing to say the least, and one for which I have no satisfactory answer. The classic problem for film adaptations of novels is how to deal with narrative standpoint, focalisation, and authorial commentary, and a reflex answer might hypothesise that George Eliot's narrators pose too great a challenge. -

Jews with Money: Yuval Levin on Capitalism Richard I

JEWISH REVIEW Number 2, Summer 2010 $6.95 OF BOOKS Ruth R. Wisse The Poet from Vilna Jews with Money: Yuval Levin on Capitalism Richard I. Cohen on Camondo Treasure David Sorkin on Steven J. Moses Zipperstein Montefiore The Spy who Came from the Shtetl Anita Shapira The Kibbutz and the State Robert Alter Yehuda Halevi Moshe Halbertal How Not to Pray Walter Russell Mead Christian Zionism Plus Summer Fiction, Crusaders Vanquished & More A Short History of the Jews Michael Brenner Editor Translated by Jeremiah Riemer Abraham Socher “Drawing on the best recent scholarship and wearing his formidable learning lightly, Michael Publisher Brenner has produced a remarkable synoptic survey of Jewish history. His book must be considered a standard against which all such efforts to master and make sense of the Jewish Eric Cohen past should be measured.” —Stephen J. Whitfield, Brandeis University Sr. Contributing Editor Cloth $29.95 978-0-691-14351-4 July Allan Arkush Editorial Board Robert Alter The Rebbe Shlomo Avineri The Life and Afterlife of Menachem Mendel Schneerson Leora Batnitzky Samuel Heilman & Menachem Friedman Ruth Gavison “Brilliant, well-researched, and sure to be controversial, The Rebbe is the most important Moshe Halbertal biography of Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson ever to appear. Samuel Heilman and Hillel Halkin Menachem Friedman, two of the world’s foremost sociologists of religion, have produced a Jon D. Levenson landmark study of Chabad, religious messianism, and one of the greatest spiritual figures of the twentieth century.” Anita Shapira —Jonathan D. Sarna, author of American Judaism: A History Michael Walzer Cloth $29.95 978-0-691-13888-6 J. -

George Eliot

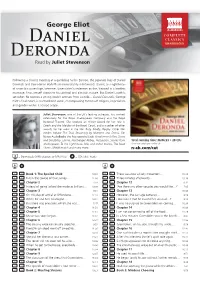

George Eliot COMPLETE CLASSICS Daniel UNABRIDGED Deronda Read by Juliet Stevenson Following a chance meeting at a gambling hall in Europe, the separate lives of Daniel Deronda and Gwendolen Harleth are immediately intertwined. Daniel, an Englishman of uncertain parentage, becomes Gwendolen’s redeemer as she, trapped in a loveless marriage, finds herself drawn to his spiritual and altruistic nature. But Daniel’s path is set when he rescues a young Jewish woman from suicide… Daniel Deronda, George Eliot’s final novel, is a remarkable work, encompassing themes of religion, imperialism and gender within its broad scope. Juliet Stevenson, one of the UK’s leading actresses, has worked extensively for the Royal Shakespeare Company and the Royal National Theatre. She received an Olivier Award for her role in Death and the Maiden at the Royal Court, and a number of other awards for her work in the filmTruly, Madly, Deeply. Other film credits include The Trial, Drowning by Numbers and Emma. For Naxos AudioBooks she has recorded Lady Windermere’s Fan, Sense and Sensibility, Emma, Northanger Abbey, Persuasion, Stories from Total running time: 36:06:33 • 28 CDs Shakespeare, To the Lighthouse, Bliss and Other Stories, The Road View our catalogue online at Home, Middlemarch and many more. n-ab.com/cat = Downloads (M4B chapters or MP3 files) = CDs (disc–track) 1 1-1 Book 1: The Spoiled Child 10:08 25 4-5 There was now a lively movement… 13:28 2 1-2 But in the course of that survey… 12:08 26 4-6 Three minutes afterwards… 13:18 3 1-3 Chapter 2 7:58 27 -

Power and Powerlessness in Jewish History, Politics & Government JUDS 0980S – Spring Semester – 2009 Research Seminar, Thurs

Zionism, Anti-Zionism & Post-Zionism 1 Brown University Program in Judaic Studies Power and Powerlessness in Jewish History, Politics & Government JUDS 0980S – Spring Semester – 2009 Research Seminar, Thurs. 4:00-6:20 Instructor: Prof. Sam Lehman-Wilzig Office: 163 George St., Room 301 (Program in Judaic Studies – 3rd floor) Office Hours: Tuesday, 10:30-11:30 AM; Thursday 3:00-3:45 PM; or by appointment (through e-mail) Phone: 863-7564 or 863-3912 E-mail: [email protected] Personal Website: www.profslw.com OCRA Code: JewPower Seminar Description & Goals The purposes of this seminar are twofold: 1- to survey and analyze the central concepts, principles, values and institutions within the Jewish tradition and Jewish history – from Biblical times to the contemporary period – that are related to the question of "power/lessness", including political, social, and economic power; 2- to have each student develop analytical tools to carry out research on one specific "power/lessness" topic (thematic research), or how power in all its manifestations was viewed and (where relevant) also used within a particular historical period/place (contextual research). The central questions that this seminar will address: What does Jewish history, as well as the normative religio-legal tradition, have to say about power relationships within the Jewish polity – between "branches" of government, as well as between governor/s and governed? What about power relationships vis-à-vis sovereign Gentile rulers when no Jewish State exists? Is the Jewish approach to the question of political power consistent over time or mutable depending on circumstances? What is the place of opposition to authority in the Jewish heritage? What types of war (and military practices) are legitimate and which aren't? What other types of "Jewish Power" have been in evidence over the past centuries in Jewish history, and how do they relate to political power? Are power relationships in the State of Israel today consonant with, or contradictory to, the Jewish heritage? The course has no formal prerequisite. -

Sholem Schwarzbard: Biography of a Jewish Assassin

Sholem Schwarzbard: Biography of a Jewish Assassin The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Johnson, Kelly. 2012. Sholem Schwarzbard: Biography of a Jewish Assassin. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:9830349 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA © 2012 Kelly Scott Johnson All rights reserved Professor Ruth R. Wisse Kelly Scott Johnson Sholem Schwarzbard: Biography of a Jewish Assassin Abstract The thesis represents the first complete academic biography of a Jewish clockmaker, warrior poet and Anarchist named Sholem Schwarzbard. Schwarzbard's experience was both typical and unique for a Jewish man of his era. It included four immigrations, two revolutions, numerous pogroms, a world war and, far less commonly, an assassination. The latter gained him fleeting international fame in 1926, when he killed the Ukrainian nationalist leader Symon Petliura in Paris in retribution for pogroms perpetrated during the Russian Civil War (1917-20). After a contentious trial, a French jury was sufficiently convinced both of Schwarzbard's sincerity as an avenger, and of Petliura's responsibility for the actions of his armies, to acquit him on all counts. Mostly forgotten by the rest of the world, the assassin has remained a divisive figure in Jewish-Ukrainian relations, leading to distorted and reductive descriptions his life. -

Daniel Deronda (BBC1) and George Eliot: a Scandalous Live (BBC2) Daniel Doronda

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by UNL | Libraries University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln The George Eliot Review English, Department of 2003 Daniel Deronda (BBC1) and George Eliot: A Scandalous Live (BBC2) Daniel Doronda Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/ger Doronda, Daniel, "Daniel Deronda (BBC1) and George Eliot: A Scandalous Live (BBC2)" (2003). The George Eliot Review. 458. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/ger/458 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the English, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in The George Eliot Review by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Daniel Deronda (BBCI) and George Eliot; A Scandalous Life (BBC2) (November-December 2002) The classic novel provides a tempting invitation for the contemporary film-maker: almost certainly it will have period costume, indoor amusements - preferably a dance, even better a ball - lavish, preferably country-house settings, consonant with outdoor amusements like a hunt or at least two or three riding sequences, and moral dilemmas which are often sexual and can be presented in modern terms - the only terms the viewing public is thought to accept. Then there is the plot, which can easily be altered or adjusted - modernized is the cosmetic word - to appeal to viewers who haven't read the novel but like to be associated with its cultural ambience, and viewers who have read it but wish to experience this alternative mode and exercize their critical judgements at the same time.