Pandemic Pop and Other Viral Sensations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

3/30/2021 Tagscanner Extended Playlist File:///E:/Dropbox/Music For

3/30/2021 TagScanner Extended PlayList Total tracks number: 2175 Total tracks length: 132:57:20 Total tracks size: 17.4 GB # Artist Title Length 01 *NSync Bye Bye Bye 03:17 02 *NSync Girlfriend (Album Version) 04:13 03 *NSync It's Gonna Be Me 03:10 04 1 Giant Leap My Culture 03:36 05 2 Play Feat. Raghav & Jucxi So Confused 03:35 06 2 Play Feat. Raghav & Naila Boss It Can't Be Right 03:26 07 2Pac Feat. Elton John Ghetto Gospel 03:55 08 3 Doors Down Be Like That 04:24 09 3 Doors Down Here Without You 03:54 10 3 Doors Down Kryptonite 03:53 11 3 Doors Down Let Me Go 03:52 12 3 Doors Down When Im Gone 04:13 13 3 Of A Kind Baby Cakes 02:32 14 3lw No More (Baby I'ma Do Right) 04:19 15 3OH!3 Don't Trust Me 03:12 16 4 Strings (Take Me Away) Into The Night 03:08 17 5 Seconds Of Summer She's Kinda Hot 03:12 18 5 Seconds of Summer Youngblood 03:21 19 50 Cent Disco Inferno 03:33 20 50 Cent In Da Club 03:42 21 50 Cent Just A Lil Bit 03:57 22 50 Cent P.I.M.P. 04:15 23 50 Cent Wanksta 03:37 24 50 Cent Feat. Nate Dogg 21 Questions 03:41 25 50 Cent Ft Olivia Candy Shop 03:26 26 98 Degrees Give Me Just One Night 03:29 27 112 It's Over Now 04:22 28 112 Peaches & Cream 03:12 29 220 KID, Gracey Don’t Need Love 03:14 A R Rahman & The Pussycat Dolls Feat. -

ANDERTON Music Festival Capitalism

1 Music Festival Capitalism Chris Anderton Abstract: This chapter adds to a growing subfield of music festival studies by examining the business practices and cultures of the commercial outdoor sector, with a particular focus on rock, pop and dance music events. The events of this sector require substantial financial and other capital in order to be staged and achieve success, yet the market is highly volatile, with relatively few festivals managing to attain longevity. It is argued that these events must balance their commercial needs with the socio-cultural expectations of their audiences for hedonistic, carnivalesque experiences that draw on countercultural understanding of festival culture (the countercultural carnivalesque). This balancing act has come into increased focus as corporate promoters, brand sponsors and venture capitalists have sought to dominate the market in the neoliberal era of late capitalism. The chapter examines the riskiness and volatility of the sector before examining contemporary economic strategies for risk management and audience development, and critiques of these corporatizing and mainstreaming processes. Keywords: music festival; carnivalesque; counterculture; risk management; cool capitalism A popular music festival may be defined as a live event consisting of multiple musical performances, held over one or more days (Shuker, 2017, 131), though the connotations of 2 the word “festival” extend much further than this, as I will discuss below. For the purposes of this chapter, “popular music” is conceived as music that is produced by contemporary artists, has commercial appeal, and does not rely on public subsidies to exist, hence typically ranges from rock and pop through to rap and electronic dance music, but excludes most classical music and opera (Connolly and Krueger 2006, 667). -

Administration of Barack Obama, 2015 Remarks at the White House

Administration of Barack Obama, 2015 Remarks at the White House Easter Egg Roll April 6, 2015 The President. Hello, everybody! Well, happy Easter. Audience members. Happy Easter! The President. We are so blessed to have this beautiful day and to have so many friends in our backyard. And Malia and Sasha, they had a little school stuff going on today, but they wanted to send their love. Bo and Sunny are here, along with the Easter Bunny. And this is always one of our favorite events. We hope you guys are having fun. This is a particularly special Easter Egg Roll because we've actually got a birthday to celebrate. It is the fifth anniversary of the First Lady's "Let's Move!" initiative. And to help us celebrate we've got the outstanding young group, Fifth Harmony, here to help us sing "Happy Birthday." Everybody ready to sing "Happy Birthday"? All right. Fifth Harmony! Audience members. Yeah! Camila Cabello. Thank you so much to the President and First Lady for having us it is such an honor and so incredibly cool to be singing at the White House. Thank you so much. Lauren Jauregui. Woo! We're so honored to be here to help sing Mrs. Obama's initiative a happy birthday. We think it's really cool that she helps people all over the Nation want to be active and want to be healthy. It's really awesome. Normani Hamilton. And because of this special occasion, we wanted to present you guys a birthday cake. [At this point, the members of First Harmony presented a cake to Mrs. -

Madonna Moves to Lisbon to Help Son David Become a Football Star

Lifestyle FRIDAY, SEPTEMBER 1, 2017 Like Destiny's Child, Fifth Harmony survives after the storm t's been a year of transition for Fifth because they're in the driver's seat. They pushed Harmony: The pop stars parted ways with for more creative control with their labels, Epic Imember Camila Cabello, switched manage- Records and Simon Cowell's Syco imprint, and ment teams, negotiated a new contract with sought legal counsel to gain ownership of the their label and won greater creative control of Fifth Harmony trademark. their brand. Luckily the newly-minted quartet, who released their third album last week, had Chart success the fairy godmother of girl groups to guide "When we hired our lawyer, Dina LaPolt, them through the tumultuous times: Destiny's that's when our real transformation began Child alum Kelly Rowland. because she really informed us about our busi- "We were advised by THE Kelly Rowland," ness and informed us about our rights as Dinah Jane, 20, said with reverence. "She just artists," Jauregui said. "And we really, I feel, told us to, like, let the music speak for itself ... gained this sort of inner power that we didn't and just know your worth, believe in yourself have before and this control and ownership of and just be there for each other. So we've defi- our music, of our brand, of our business." Fifth nitely honed into that. And for her to advise Harmony was formed on the US version of "The that, like, that says a lot because, you know, X Factor" in 2012. -

City Council AGENDA Monday, September 28, 2020 7:00 PM Page

City Council AGENDA Monday, September 28, 2020 7:00 PM Page # A. ROLL CALL B. PLEDGE OF ALLEGIANCE & MOMENT OF SILENCE C. CONSENT AGENDA 1. Approve minutes from the City Council meeting of September 14, 2020. 3 - 46 City Council Minutes 9-14-2020 2. Approve minutes from the Special Joint City Council / Planning 47 - 69 Commission meeting of September 14, 2020. Special Joint City Council / Planning Commission Minutes 9-14-2020 3. Approve minutes from the Planning Commission Meeting of August 17, 70 - 84 2020. Planning Commission Minutes 8-17-2020 4. Review minutes from the Planning Commission meeting of September 9, 85 - 161 2020. Planning Commission Minutes 9-9-2020 5. Review minutes from the Parks and Recreation Advisory Board meeting 162 - 172 of August 6, 2020. Parks and Recreation Advisory Board Minutes 8-6-2020 6. Consider accepting the dedication of land, or an interest therein for 173 - 177 public purposes, contained in FP-20-20-09, Final Plat for Hawaiian Brothers Restaurant located at 11600 Shawnee Mission Parkway. On September 9, 2020, the Planning Commission recommended 11-0 that the Governing Body accept the dedication of land or an interest therein for public purposes. Recommendation: Consider accepting the dedication of land, or an interest therein for public purposes, contained in FP-20-20-09. Memo and Attachments - Pdf 7. Consider approval of SUP-12-20-09, a special use permit for Gumshoe 178 - 183 Daycare, an in-home daycare located at 12110 W. 68th Terrace. On September 9, 2020, the Planning Commission recommended 11-0 that the Governing Body approve the special use permit subject to the conditions in the staff report. -

View Full Article

ARTICLE ADAPTING COPYRIGHT FOR THE MASHUP GENERATION PETER S. MENELL† Growing out of the rap and hip hop genres as well as advances in digital editing tools, music mashups have emerged as a defining genre for post-Napster generations. Yet the uncertain contours of copyright liability as well as prohibitive transaction costs have pushed this genre underground, stunting its development, limiting remix artists’ commercial channels, depriving sampled artists of fair compensation, and further alienating netizens and new artists from the copyright system. In the real world of transaction costs, subjective legal standards, and market power, no solution to the mashup problem will achieve perfection across all dimensions. The appropriate inquiry is whether an allocation mechanism achieves the best overall resolution of the trade-offs among authors’ rights, cumulative creativity, freedom of expression, and overall functioning of the copyright system. By adapting the long-standing cover license for the mashup genre, Congress can support a charismatic new genre while affording fairer compensation to owners of sampled works, engaging the next generations, and channeling disaffected music fans into authorized markets. INTRODUCTION ........................................................................ 443 I. MUSIC MASHUPS ..................................................................... 446 A. A Personal Journey ..................................................................... 447 B. The Mashup Genre .................................................................... -

Shawn Mendes & Camila Cabello

538 TOP 50 30 AUGUSTUS 2019 538.NL/TOP50 1=10# 1 SHAWN MENDES & CAMILA CABELLO SEÑORITA 2=16# 2 3=6# 3 5+17# 4 ED SHEERAN & JUSTIN SNELLE MEDUZA FEAT. BIEBER GOODBOYS I DON’T CARE REÜNIE PIECE OF YOUR HEART 6+9# 5 4-13# 6 8+9# 7 ED SHEERAN FEAT. TIËSTO, JONAS BLUE & R3HAB & A TOUCH OF KHALID RITA ORA CLASS BEAUTIFUL RITUAL ALL AROUND THE PEOPLE WORLD (LA LA LA) 11+6# 8 7-16# 9 16+13# DJ SNAKE FEAT. J MARCO BORSATO, AVICII FEAT. CHRIS BALVIN & TYGA ARMIN VAN BUUREN & MARTIN LOCO CONTIGO DAVINA MICHELLE HEAVEN HOE HET DANST DIMITRI VEGAS & LIKE MIKE, DAVID GUETTA & DADDY YANKEE INSTAGRAM 13+8# KYGO & WHITNEY HOUSTON HIGHER LOVE 10-10# KRIS KROSS AMSTERDAM, KRAANTJE PAPPIE & TABITHA MOMENT 9-15# LAUREN DAIGLE YOU SAY 12-11# LIL NAS X FEAT. BILLY RAY CYRUS OLD TOWN ROAD 14-21# SAM SMITH HOW DO YOU SLEEP? 18+6# DAVINA MICHELLE BETTER NOW 17=3# ARMIN VAN BUUREN & AVIAN GRAYS FEAT. JORDAN SHAW SOMETHING REAL 19+5# SUZAN & FREEK BLAUWE DAG 23+9# PINK FEAT. KHALID HURTS 2B HUMAN 27+2# KRIS KROSS AMSTERDAM & NIELSON IK STA JOU BETER 25+6# LEWIS CAPALDI SOMEONE YOU LOVED 15-18# POST MALONE FEAT. YOUNG THUG GOODBYES 26+8# MABEL MAD LOVE 24=10# MARTIN GARRIX FEAT. BONN HOME 42+2# MAAN ZO KAN HET DUS OOK 21-7# LUIS FONSI, SEBASTIAN YATRA & NICKY JAM DATE LA VUELTA 20-19# MARTIN GARRIX FEAT. JRM THESE ARE THE TIMES 29+7# NORMANI MOTIVATION 36+2# AVICII FEAT. -

Holiday Help by Alicia Feyerherm Lundmark Got the Word out Hays High Guidon About the Program and Accrued 25 Interested Senior Citizens

END OF THE DECADE ART WALK As 2020 approaches, Students participate in the Winter Art it is important to remember Walk in a variety of ways, from showing the last decade artwork to singing to selling items Page 6 Page 12 THE VOL. 94 NO. 4 • HAYS HIGH SCHOOL 2300 E. 13th ST. • HAYS, KAN. 67601 www.hayshighguidon.com G DECEMBER 18, 2019 N FRIENDLY LETTERS UIDOSEASON OF GIVING Instructor initiates new Pen Pal program Holiday Help By Alicia Feyerherm Lundmark got the word out Hays High Guidon about the program and accrued 25 interested senior citizens. Standing at Homestead “Some [senior citizens] Projects created to benefit families in need Health, instructor Luke Lun- are from as far away as dmark watched his son carol Arizona, and others are By Michaela Austin Hays High Guidon with his Cub Scout troop and as close as just down the witnessed the joy the chil- street,” Lundmark said. During the holidays, there dren brought to the residents. Lundmark said he hopes the are many things that people “I saw the interaction between program will help brighten the think about, such as giving the kids and lives of senior the right gifts and spending the senior citi- citizens who time with family and friends. zens, and may be lonely One of the biggest ideas that the citizens There are seniors in the nurs- is suggested during the holi- seemed to be ing homes and day season, though, is giv- filled with so in the area that assisted liv- ing to and helping out others. -

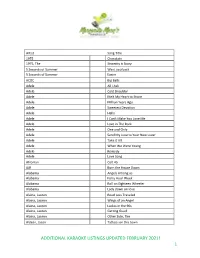

Additional Karaoke Listings Updated February 2021! 1

Artist Song Title 1975 Chocolate 1975, The Sincerity is Scary 5 Seconds of Summer Want you back 5 Seconds of Summer Easier ACDC Big Balls Adele All I Ask Adele Cold Shoulder Adele Melt My Heart to Stone Adele Million Years Ago Adele Sweetest Devotion Adele Hello Adele I Can't Make You Love Me Adele Love in The Dark Adele One and Only Adele Send My Love to Your New Lover Adele Take It All Adele When We Were Young Adele Remedy Adele Love Song Afroman Colt 45 AJR Burn the House Down Alabama Angels Among us Alabama Forty Hour Week Alabama Roll on Eighteen Wheeler Alabama Lady down on love Alaina, Lauren Road Less Traveled Alaina, Lauren Wings of an Angel Alaina, Lauren Ladies in the 90s Alaina, Lauren Getting Good Alaina, Lauren Other Side, The Aldean, Jason Tattoos on this town ADDITIONAL KARAOKE LISTINGS UPDATED FEBRUARY 2021! 1 Aldean, Jason Just Getting Started Aldean, Jason Lights Come On Aldean, Jason Little More Summertime, A Aldean, Jason This Plane Don't Go There Aldean, Jason Tonight Looks Good On You Aldean, Jason Gettin Warmed up Aldean, Jason Truth, The Aldean, Jason You make it easy Aldean, Jason Girl Like you Aldean, Jason Camouflage Hat Aldean, Jason We Back Aldean, Jason Rearview Town Aldean, Jason & Miranda Lambert Drowns The Whiskey Alice in Chains Man In The Box Alice in Chains No Excuses Alice in Chains Your Decision Alice in Chains Nutshell Alice in Chains Rooster Allan, Gary Every Storm (Runs Out of Rain) Allan, Gary Runaway Allen, Jimmie Best shot Anderson, John Swingin' Andress, Ingrid Lady Like Andress, Ingrid More Hearts Than Mine Angels and Airwaves Kiss & Tell Angston, Jon When it comes to loving you Animals, The Bring It On Home To Me Arctic Monkeys Do I Wanna Know Ariana Grande Breathin Arthur, James Say You Won't Let Go Arthur, James Naked Arthur, James Empty Space ADDITIONAL KARAOKE LISTINGS UPDATED FEBRUARY 2021! 2 Arthur, James Falling like the stars Arthur, James & Anne Marie Rewrite the Stars Arthur, James & Anne Marie Rewrite The Stars Ashanti Happy Ashanti Helpless (ft. -

Rekordmange Vil Være Med I Dronning Sonjas Musikkonkurranse I År NTB Tema

Nyheter - Dronning Sonja Internasjonale Musikkonkurranse Uttak 26.08.2019 Rekordmange vil være med i Dronning Sonjas musikkonkurranse i år NTB Tema. 12.04.2019 NTB 304 sangere fra 49 nasjoner har søkt om å få være med når Dronning Sonja Internasjonale Musikkonkurranse arrangeres for 15. gang i august. Det er ny rekord, ifølge pressemeldingen. De som vil være med i konkurransen, som arrangeres annethvert år, er et internasjonalt toppsjikt av sangere på trappene til internasjonal karriere. Blant annet sender ledende operahus som Metropolitan Opera i New York, Bolsjoj Teater i Moskva, Royal Opera Covent Garden i London og La Scala Opera i Milano sine fremste aspiranter. – Konkurransen opplever nå betydelig internasjonal oppmerksomhet. Det gjenspeiler seg i den store søknadsmengden og de mange nasjonene som er representert på søkerlisten, sier daglig leder Lars Hallvard Flæten. Etter at en skandinavisk sammensatt jury har vurdert alle søknadene, basert på videomateriale, vil rundt 40 sangere inviteres til Oslo i august måned. Finalekonserten er i Operaen 23. august, der dronning Sonja selv deler ut prisene. Vinneren får nær en halv million kroner. 304 sangere har søkt om deltagelse i Dronning Sonja Internasjonale Musikkonkurranse 2019. Her er dronningen med 2017-vinner Seungju Bahg fra Sør-Korea. Foto: Terje Bendiksby / NTB scanpix © NTB Tema Alle artikler er beskyttet av lov om opphavsrett til åndsverk. Artikler må ikke videreformidles utenfor egen organisasjon uten godkjenning fra Retriever eller den enkelte utgiver. Les hele nyheten på http://ret.nu/P3nhQTcN Side 3 av 90 Nyheter - Dronning Sonja Internasjonale Musikkonkurranse Uttak 26.08.2019 Rekordmange vil være med i Dronning Sonjas musikkonkurranse i år Sunnmørsposten. -

VIPNEWSPREMIUM > VOLUME 225 > AUGUST 2019

15 14 7 16 3 VIPNEWS PREMIUM > VOLUME 225 > AUGUST 2019 4 13 6 19 12 9 2 VIPNEWS > AUGUST 2019 McGowan’s Musings So, how did you manage to get through resulting in emergency measures in France. the stage in 2069 I wonder – I’m pretty sure these summer months without us? A fair This year’s edition of Glastonbury was one of I’ll be otherwise engaged! amount has happened since we were last in the hottest ever. Then unusually high winds touch in June, heat waves, high winds, and had their effect on festivals and other events But maybe a festival encouraging alien for us, a new Prime Minister! I can’t quite and attractions. In the UK large events such as visitors may offer something different, express the deep joy and optimism I feel for Boardmasters and Houghton were cancelled, ‘Alienstock’, an Area 51 themed event has our European future now that Boris Johnson and In Winchester, at the Boomtown Fair, been announced to supposedly take place is at the helm – no, you’re right I’m not being dozens of tents were wrecked overnight close to the town of Rachel, (population 50!) serious! Anyway what was that? You think on Friday after 52 mile an hour winds tore Nevada, close to the US Air Force base, which I’m just going to use this intro as an excuse through the campsites. alienists believe houses alien technology. to talk about the bloody weather again…. Coordinators of the now-defunct “Storm well, actually yes I am, as it has to say the I was in Serbia for the EXIT Festival in early Area 51” are now planning a full-fledged least been more than erratic; The summer July, where Ruud Berends myself and others music festival supposedly to take place next kicked off in June , as I’m sure many of you cleverly managed to secure ourselves in month. -

Karaoke Book

10 YEARS 3 DOORS DOWN 3OH!3 Beautiful Be Like That Follow Me Down (Duet w. Neon Hitch) Wasteland Behind Those Eyes My First Kiss (Solo w. Ke$ha) 10,000 MANIACS Better Life StarStrukk (Solo & Duet w. Katy Perry) Because The Night Citizen Soldier 3RD STRIKE Candy Everybody Wants Dangerous Game No Light These Are Days Duck & Run Redemption Trouble Me Every Time You Go 3RD TYME OUT 100 PROOF AGED IN SOUL Going Down In Flames Raining In LA Somebody's Been Sleeping Here By Me 3T 10CC Here Without You Anything Donna It's Not My Time Tease Me Dreadlock Holiday Kryptonite Why (w. Michael Jackson) I'm Mandy Fly Me Landing In London (w. Bob Seger) 4 NON BLONDES I'm Not In Love Let Me Be Myself What's Up Rubber Bullets Let Me Go What's Up (Acoustative) Things We Do For Love Life Of My Own 4 PM Wall Street Shuffle Live For Today Sukiyaki 110 DEGREES IN THE SHADE Loser 4 RUNNER Is It Really Me Road I'm On Cain's Blood 112 Smack Ripples Come See Me So I Need You That Was Him Cupid Ticket To Heaven 42ND STREET Dance With Me Train 42nd Street 4HIM It's Over Now When I'm Gone Basics Of Life Only You (w. Puff Daddy, Ma$e, Notorious When You're Young B.I.G.) 3 OF HEARTS For Future Generations Peaches & Cream Arizona Rain Measure Of A Man U Already Know Love Is Enough Sacred Hideaway 12 GAUGE 30 SECONDS TO MARS Where There Is Faith Dunkie Butt Closer To The Edge Who You Are 12 STONES Kill 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER Crash Rescue Me Amnesia Far Away 311 Don't Stop Way I Feel All Mixed Up Easier 1910 FRUITGUM CO.