Owners Versus Bubu Gujin: Land Rights and Getting the Language Right in Guugu Yimithirr Country

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Traditional Owners and Sea Country in the Southern Great Barrier Reef – Which Way Forward?

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by ResearchOnline at James Cook University Final Report Traditional Owners and Sea Country in the Southern Great Barrier Reef – Which Way Forward? Allan Dale, Melissa George, Rosemary Hill and Duane Fraser Traditional Owners and Sea Country in the Southern Great Barrier Reef – Which Way Forward? Allan Dale1, Melissa George2, Rosemary Hill3 and Duane Fraser 1The Cairns Institute, James Cook University, Cairns 2NAILSMA, Darwin 3CSIRO, Cairns Supported by the Australian Government’s National Environmental Science Programme Project 3.9: Indigenous capacity building and increased participation in management of Queensland sea country © CSIRO, 2016 Creative Commons Attribution Traditional Owners and Sea Country in the Southern Great Barrier Reef – Which Way Forward? is licensed by CSIRO for use under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Australia licence. For licence conditions see: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry: 978-1-925088-91-5 This report should be cited as: Dale, A., George, M., Hill, R. and Fraser, D. (2016) Traditional Owners and Sea Country in the Southern Great Barrier Reef – Which Way Forward?. Report to the National Environmental Science Programme. Reef and Rainforest Research Centre Limited, Cairns (50pp.). Published by the Reef and Rainforest Research Centre on behalf of the Australian Government’s National Environmental Science Programme (NESP) Tropical Water Quality (TWQ) Hub. The Tropical Water Quality Hub is part of the Australian Government’s National Environmental Science Programme and is administered by the Reef and Rainforest Research Centre Limited (RRRC). -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UM l films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type o f computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely afreet reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UME a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, b^inning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back o f the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy, ffigher quality 6” x 9” black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UM l directly to order. UMl A Bell & Howell Infoimation Company 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor MI 48106-1346 USA 313/761-4700 800/521-0600 Velar-Initial Etyma and Issues in Comparative Pama-Nyungan by Susan Ann Fitzgerald B.A.. University of V ictoria. 1989 VI.A. -

Tropical Water Quality Hub Indigenous Engagement and Participation Strategy Version 1 – FINAL

Tropical Water Quality Hub Indigenous Engagement and Participation Strategy Version 1 – FINAL NESP Tropical Water Quality Hub CONTENTS ACRONYMS ......................................................................................................................... II ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ....................................................................................................... II INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................... 3 OBJECTIVES ........................................................................................................................ 4 IMPLEMENTATION OF THE OBJECTIVES .......................................................................... 5 PERFORMANCE INDICATORS ............................................................................................ 9 IDENTIFIED COMMUNICATION CHANNELS .....................................................................10 FURTHER INFORMATION ..................................................................................................10 APPENDIX A: INDIGENOUS ORGANISATIONS .................................................................11 APPENDIX B: GUIDELINES FOR RESEARCH IN THE TORRES STRAIT ..........................14 VERSION CONTROL REVISION HISTORY Comment (review/amendment Version Date Reviewed by (Name, Position) type) Julie Carmody, Senior Research Complete draft document 0.1 23/04/15 Manager, RRRC 0.2 28/04/15 Melissa George, CEO, NAILSMA Review – no changes 0.3 30/04/15 -

Eastern Kuku Yalanji People's Native Title Determination

Noah Beach on the coastline in Eastern Kuku Yalanji country. Eastern Kuku Yalanji People’s native title determination Far north Queensland 9 December 2007 Resolution of native title issues over land and waters. Eastern Kuku Yalanji People’s rights On 9 December 2007 the Federal Court of Australia made • access, camp on or traverse the area a consent determination recognising the Eastern Kuku • hunt animals, gather plants (except in some Yalanji People’s native title rights and interests over specified coastal areas) and take natural resources 126,900 ha of land and waters in far north Queensland. for personal, domestic needs, but not for trade or The determination area includes term and special leases, commerce a timber reserve and Unallocated State Land. • conduct ceremonies • be buried in the ground The consent determination is an important turning • maintain springs and wells where the underground point because it formally recognises the Eastern Kuku water rises naturally, for personal, domestic and Yalanji People’s native title rights under Australian law non-commercial, communal needs for the first time. • inherit and succeed to their native title rights and interests. Exclusive native title rights The Federal Court recognised that the Eastern Kuku Native title rights to water Yalanji People have exclusive native title rights The Federal Court recognised that the Eastern Kuku over 30,300 ha of Unallocated State Land in the Yalanji People also have the non-exclusive native title determination area. rights to: • hunt and fish in, or gather from, the water for These are the rights to: personal, domestic and non-commercial communal • possess, occupy and use the area to the exclusion of purposes all others • take, use and enjoy the water to satisfy personal, • inherit and succeed to the native title rights and domestic, communal needs but not for commercial interests. -

Noun Phrase Constituency in Australian Languages: a Typological Study

Linguistic Typology 2016; 20(1): 25–80 Dana Louagie and Jean-Christophe Verstraete Noun phrase constituency in Australian languages: A typological study DOI 10.1515/lingty-2016-0002 Received July 14, 2015; revised December 17, 2015 Abstract: This article examines whether Australian languages generally lack clear noun phrase structures, as has sometimes been argued in the literature. We break up the notion of NP constituency into a set of concrete typological parameters, and analyse these across a sample of 100 languages, representing a significant portion of diversity on the Australian continent. We show that there is little evidence to support general ideas about the absence of NP structures, and we argue that it makes more sense to typologize languages on the basis of where and how they allow “classic” NP construal, and how this fits into the broader range of construals in the nominal domain. Keywords: Australian languages, constituency, discontinuous constituents, non- configurationality, noun phrase, phrase-marking, phrasehood, syntax, word- marking, word order 1 Introduction It has often been argued that Australian languages show unusual syntactic flexibility in the nominal domain, and may even lack clear noun phrase struc- tures altogether – e. g., in Blake (1983), Heath (1986), Harvey (2001: 112), Evans (2003a: 227–233), Campbell (2006: 57); see also McGregor (1997: 84), Cutfield (2011: 46–50), Nordlinger (2014: 237–241) for overviews and more general dis- cussion of claims to this effect. This idea is based mainly on features -

Aboriginal Rock Art and Dendroglyphs of Queensland's Wet Tropics

ResearchOnline@JCU This file is part of the following reference: Buhrich, Alice (2017) Art and identity: Aboriginal rock art and dendroglyphs of Queensland's Wet Tropics. PhD thesis, James Cook University. Access to this file is available from: https://researchonline.jcu.edu.au/51812/ The author has certified to JCU that they have made a reasonable effort to gain permission and acknowledge the owner of any third party copyright material included in this document. If you believe that this is not the case, please contact [email protected] and quote https://researchonline.jcu.edu.au/51812/ Art and Identity: Aboriginal rock art and dendroglyphs of Queensland’s Wet Tropics Alice Buhrich BA (Hons) July 2017 Submitted as part of the research requirements for Doctor of Philosophy, College of Arts, Society and Education, James Cook University Acknowledgements First, I would like to thank the many Traditional Owners who have been my teachers, field companions and friends during this thesis journey. Alf Joyce, Steve Purcell, Willie Brim, Alwyn Lyall, Brad Grogan, Billie Brim, George Skeene, Brad Go Sam, Marita Budden, Frank Royee, Corey Boaden, Ben Purcell, Janine Gertz, Harry Gertz, Betty Cashmere, Shirley Lifu, Cedric Cashmere, Jeanette Singleton, Gavin Singleton, Gudju Gudju Fourmile and Ernie Grant, it has been a pleasure working with every one of you and I look forward to our future collaborations on rock art, carved trees and beyond. Thank you for sharing your knowledge and culture with me. This thesis would never have been completed without my team of fearless academic supervisors and mentors, most importantly Dr Shelley Greer. -

Torres and Cape Hospital and Health Service

Torres and Cape Hospital and Health Service 2019–2020 Annual Report 2019-20 1 Information about consultancies, overseas travel, and the Queensland language services policy is available at the Queensland Government Open Data website (qld.gov.au/data). An electronic copy of this report is available at https://www.health.qld.gov.au/torres-cape/html/publication-scheme. Hard copies of the annual report are available by contacting the Board Secretary (07) 4226 5945. Alternatively, you can request a copy by emailing [email protected]. The Queensland Government is committed to providing accessible services to Queenslanders from all culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds. If you have difficulty in understanding the annual report, you can contact us on telephone (07) 4226 5974 and we will arrange an interpreter to effectively communicate the report to you. This annual report is licensed by the State of Queensland (Torres and Cape Hospital and Health Service) under a Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) 4.0 International license. You are free to copy, communicate and adapt this annual report, as long as you attribute the work to the State of Queensland (Torres and Cape Hospital and Health Service). To view a copy of this license, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ Content from this annual report should be attributed as: State of Queensland (Torres and Cape Hospital and Health Service) Annual Report 2018–19. © Torres and Cape Hospital and Health Service 2019 ISSN 2202-6401 (Print) ISSN 2203-8825 (Online) Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people are advised that this publication may contain words, names, images and descriptions of people who have passed away. -

Download the Rainforest Aboriginal News (PDF, 2.3MB)

Traditional 0wner Leadership Group The Traditional Owner Leadership Group (TOLG) consists of: Kaylene Malthouse, Updates Alwyn Lyall, Tracey Heenan and Victor Maund (North Queensland Land Council Board Directors); Allison Halliday (Indigenous Director, Terrain NRM); and Phil What’s been happening Rist, Leah Talbot, Joann Schmider, John Locke, Dennis Ah Kee and Seraeah Wyles (WTMA Indigenous Advisory Committee members). in the Wet Tropics… International Women’s Day 6 March 2018 ISSUE SIX : June 2018 Wet Tropics Tour Guide Program workshops 6–7 March 2018 Celebrating Rainforest Aboriginal women: Wet Tropics Tour Guide Program NRM update field school Mandingalbay Yidinji Fire has been on the horizon lately! It’s been great to see Girringun’s TOLG’s first meeting was held 23 March, 2018. The group considered the outcomes of country 16–17 March 2018 fire program, which is supported the Rainforest Aboriginal People’s Regional Workshop at Palm Cove, 21–22 October Wet Tropics Traditional Owner by Terrain, build on last year’s 2017, and also began to develop a collaborative framework/implementation plan Leadership Group (TOLG) meeting experience. Girringun recently led for refreshing the Regional Agreement. The refresh will continue through a series 23 March 2018 their second burn, and 11 rangers of negotiations between original signatories, Traditional Owners across the Wet Cairns ECOfiesta 3 June 2018 completed their level 1 fire training. Tropics, the Authority, and the State and Commonwealth governments. The TOLG Reconciliation Week 27 May–3 June Controlled burns will also take place also aims to ensure the updated Wet Tropics Management Plan 1998 is a document 2018 in the Cooktown region over coming that appropriately recognises the rights and interests of Rainforest Aboriginal World Heritage update months, completing fire training for people, many of which have already been articulated in the Wet Tropics Regional Community Consultative Committee Welcome to the sixth Rainforest The first Traditional Owner Leadership Jabalbina and Bulmba rangers, Mamu Agreement. -

Jennyfer Taylor Thesis (PDF 12MB)

This page is intentionally left blank. NGANA WUBULKU JUNKURR-JIKU BALKAWAY-KA: THE INTERGENERATIONAL CO-DESIGN OF A TANGIBLE TECHNOLOGY TO KEEP ACTIVE USE OF THE KUKU YALANJI ABORIGINAL LANGUAGE STRONG Jennyfer Lawrence Taylor BA ANU BInfTech ANU BInfTech(Hons) QUT FHEA Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Computer Science Science and Engineering Faculty Queensland University of Technology in partnership with Wujal Wujal Aboriginal Shire Council 2020 This page is intentionally left blank. KeyworDs Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander languages, active language use, co-design, community-based participatory design, human-computer interaction, Indigenous languages, intergenerational language transmission, language revitalisation, participatory design, social technologies, tangible user interfaces. i MessaGe to AboriGinal anD Torres Strait IslanDer ReaDers This thesis may contain images and content about people who have passed away. The names of people involved in the project are listed in the Acknowledgements section, and Figure 3, Figure 6, and Figure 14 contain images of Elders. MessaGe to All ReaDers Wujal Wujal Aboriginal Shire Council is the partner for this project. This publication, and quotes from participants included within this publication, should not be reproduced without permission from Wujal Wujal Aboriginal Shire Council. This thesis is freely available online on the QUT EPrints website, and the hard copies made available to the Wujal Wujal community are not for sale. Cover Artwork The cover artwork for this thesis was painted by Cedric Sam Friday, for this book about the project that will be displayed in the Wujal Wujal Indigenous Knowledge Centre Library. The Language Reference Group chose the images to appear on the covers. -

Land and Language in Cape York Peninsula and the Gulf

Land and Language in Cape york peninsula and the Gulf Country edited by Jean-Christophe Verstraete and Diane Hafner x + 492 pp., John Benjamins Publishing Company, Amsterdam and Philadelphia, 2016, ISBN 9789027244543 (hbk), US$165.00. Review by Fiona Powell This volume is number 18 in the series Culture and Language Use (CLU), Studies in Anthropological Linguistics, edited by Gunter Seft of the Max Planck Institute for Psycholinguistics, Nijmegen. It is a Festschrift for Emeritus Professor Bruce Rigsby. His contributions to anthropology during his tenure as professor at the University of Queensland from 1975 until 2000 and his contributions to native title have profoundly enriched the lives of his students, his colleagues and the Aboriginal people of Cape York. The editors and the contributors have produced a volume of significant scholarship in honour of Bruce Rigsby. As mentioned by the editors: ‘it is difficult to do justice to even the Australian part of Bruce’s work, because he has worked on such a wide range of topics and across the boundaries of disciplines’ (p. 9). The introductory chapter outlines the development of the Queensland School of Anthropology since 1975. Then follow 19 original articles contributed by 24 scholars. The articles are arranged in five sections (Reconstructions, World Views, Contacts and Contrasts, Transformations and Repatriations). At the beginning of the volume there are two general maps (Map 1 of Queensland and Map 2 of Cape York Peninsula and the Gulf Country) both showing locations mentioned in the text. There are three indexes: of places (pp. 481–82; languages, language families and groups (pp. -

Skin, Kin and Clan: the Dynamics of Social Categories in Indigenous

Skin, Kin and Clan THE DYNAMICS OF SOCIAL CATEGORIES IN INDIGENOUS AUSTRALIA Skin, Kin and Clan THE DYNAMICS OF SOCIAL CATEGORIES IN INDIGENOUS AUSTRALIA EDITED BY PATRICK MCCONVELL, PIERS KELLY AND SÉBASTIEN LACRAMPE Published by ANU Press The Australian National University Acton ACT 2601, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at press.anu.edu.au A catalogue record for this book is available from the National Library of Australia ISBN(s): 9781760461638 (print) 9781760461645 (eBook) This title is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0). The full licence terms are available at creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ legalcode Cover design and layout by ANU Press. Cover image Gija Kinship by Shirley Purdie. This edition © 2018 ANU Press Contents List of Figures . vii List of Tables . xi About the Cover . xv Contributors . xvii 1 . Introduction: Revisiting Aboriginal Social Organisation . 1 Patrick McConvell 2 . Evolving Perspectives on Aboriginal Social Organisation: From Mutual Misrecognition to the Kinship Renaissance . 21 Piers Kelly and Patrick McConvell PART I People and Place 3 . Systems in Geography or Geography of Systems? Attempts to Represent Spatial Distributions of Australian Social Organisation . .43 Laurent Dousset 4 . The Sources of Confusion over Social and Territorial Organisation in Western Victoria . .. 85 Raymond Madden 5 . Disputation, Kinship and Land Tenure in Western Arnhem Land . 107 Mark Harvey PART II Social Categories and Their History 6 . Moiety Names in South-Eastern Australia: Distribution and Reconstructed History . 139 Harold Koch, Luise Hercus and Piers Kelly 7 . -

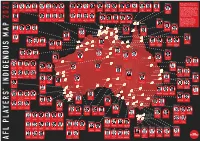

2021 Indigenous Player

Larrakia Kija Tiwi Malak Malak Warray Jawoyn Warramungu Waiben Island Meriam Mir NB: Player images may appear twice as players have provided information for multiple language and/or cultural groups. DISCLAIMER : This map indicates only the general location of larger groupings of Mia King people, which may include smaller groups Trent Burgoyne Steven May Steven Motlop Brandan Parfitt Jy Farrar Liam Jones Shane McAdam Mikayla Morrison Janet Baird Ben Long Sean Lemmens Anthony McDonald- Ben Long Shaun Burgoyne Trent Burgoyne Keidean Coleman Blake Coleman Jed Anderson Brandan Parfitt Ben Davis ST KILDA HAWTHORN PORT BRISBANE BRISBANE NORTH NORTH GEELONG ADELAIDE such as clans, dialects or individual PORT MELBOURNE PORT ADELAIDE GEELONG GOLD COAST CARLTON ADELAIDE FREMANTLE GOLD COAST ST KILDA GOLD COAST Tipungwuti MELBOURNE ADELAIDE ESSENDON ADELAIDE MELBOURNE Alicia Janz languages in a group. Boundaries are not WEST COAST intended to be exact. For more detailed EAGLES Iwaidja Dalabon information about the groups of people in a particular region contact the relevant land council. Not suitable for use in native title and other land claims. Names and regions as used in the Yupangathi Encyclopedia of Aboriginal Australia Stephanie Williams Irving Mosquito Krstel Petrevski Sam Petrevski-Seton Leno Thomas Danielle Ponter Daniel Rioli Willie Rioli Maurice Rioli Jnr GEELONG ESSENDON MELBOURNE CARLTON FREMANTLE ADELAIDE RICHMOND WEST COAST RICHMOND Waiben (D. Horton, General Editor) published EAGLES Janet Baird Nakia Cockatoo Stephanie Williams Keidean Coleman Blake Coleman Island Yirrganydji in 1994 by the Australian Institute of GOLD COAST BRISBANE GEELONG BRISBANE BRISBANE Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Meriam Mìr Studies (Aboriginal Studies Press) Jaru Kuku-Yalanji GPO Box 553 Canberra, Act 2601.