Japan's Long-Term Population Decrease and the Implications For

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1332 Nippon Suisan Kaisha, Ltd. 50 1333 Maruha Nichiro Corp. 500 1605 Inpex Corp

Nikkei Stock Average - Par Value (Update:August/1, 2017) Code Company Name Par Value(Yen) 1332 Nippon Suisan Kaisha, Ltd. 50 1333 Maruha Nichiro Corp. 500 1605 Inpex Corp. 125 1721 Comsys Holdings Corp. 50 1801 Taisei Corp. 50 1802 Obayashi Corp. 50 1803 Shimizu Corp. 50 1808 Haseko Corp. 250 1812 Kajima Corp. 50 1925 Daiwa House Industry Co., Ltd. 50 1928 Sekisui House, Ltd. 50 1963 JGC Corp. 50 2002 Nisshin Seifun Group Inc. 50 2269 Meiji Holdings Co., Ltd. 250 2282 Nh Foods Ltd. 50 2432 DeNA Co., Ltd. 500/3 2501 Sapporo Holdings Ltd. 250 2502 Asahi Group Holdings, Ltd. 50 2503 Kirin Holdings Co., Ltd. 50 2531 Takara Holdings Inc. 50 2768 Sojitz Corp. 500 2801 Kikkoman Corp. 50 2802 Ajinomoto Co., Inc. 50 2871 Nichirei Corp. 100 2914 Japan Tobacco Inc. 50 3086 J.Front Retailing Co., Ltd. 100 3099 Isetan Mitsukoshi Holdings Ltd. 50 3101 Toyobo Co., Ltd. 50 3103 Unitika Ltd. 50 3105 Nisshinbo Holdings Inc. 50 3289 Tokyu Fudosan Holdings Corp. 50 3382 Seven & i Holdings Co., Ltd. 50 3401 Teijin Ltd. 250 3402 Toray Industries, Inc. 50 3405 Kuraray Co., Ltd. 50 3407 Asahi Kasei Corp. 50 3436 SUMCO Corp. 500 3861 Oji Holdings Corp. 50 3863 Nippon Paper Industries Co., Ltd. 500 3865 Hokuetsu Kishu Paper Co., Ltd. 50 4004 Showa Denko K.K. 500 4005 Sumitomo Chemical Co., Ltd. 50 4021 Nissan Chemical Industries, Ltd. 50 4042 Tosoh Corp. 50 4043 Tokuyama Corp. 50 WF-101-E-20170803 Copyright © Nikkei Inc. All rights reserved. 1/5 Nikkei Stock Average - Par Value (Update:August/1, 2017) Code Company Name Par Value(Yen) 4061 Denka Co., Ltd. -

Anellotech Plas-Tcat Funding from R Plus Japan Press Release June 30

Anellotech Secures Funds to Develop Innovative Plas-TCatTM Plastics Recycling Technology from R Plus Japan, a New Joint Venture Company launched by 12 Cross-Industry Partners within the Japanese Plastic Supply Chain Pearl River, NY, USA, (June 30, 2020) —Sustainable technology company Anellotech has announced that R Plus Japan Ltd., a new joint venture company, will invest in the development of Anellotech’s cutting-edge Plas-TCatTM technology for recycling used plastics. R Plus Japan was established by 12 cross-industry partners within the Japanese plastics supply chain. Member partners include Suntory MONOZUKURI Expert Ltd. (SME, a subsidiary of Suntory Holdings Ltd.), TOYOBO Co. Ltd., Rengo Co. Ltd., Toyo Seikan Group Holdings Ltd., J&T Recycling Corporation, Asahi Group Holdings Ltd., Iwatani Corporation, Dai Nippon Printing Co. Ltd., Toppan Printing Co. Ltd., Fuji Seal International Inc., Hokkaican Co. Ltd., Yoshino Kogyosho Co. Ltd.. Many plastic packaging materials are unable to be recycled and are instead thrown away after a single use, often landfilled, incinerated, or littered, polluting land and oceans. Unlike the existing multi-step processes which first liquefy plastic waste back into low value “synthetic oil” intermediate products, Anellotech’s Plas- TCat chemical recycling technology uses a one-step thermal-catalytic process to convert single-use plastics directly into basic chemicals such as benzene, toluene, xylenes (BTX), ethylene, and propylene, which can then be used to make new plastics. The technology’s process efficiency has the potential to significantly reduce CO2 emissions and energy consumption. Once utilized across the industry, this technology will be able to more efficiently recycle single-use plastic, one of the world’s most urgent challenges. -

Whither the Keiretsu, Japan's Business Networks? How Were They Structured? What Did They Do? Why Are They Gone?

IRLE IRLE WORKING PAPER #188-09 September 2009 Whither the Keiretsu, Japan's Business Networks? How Were They Structured? What Did They Do? Why Are They Gone? James R. Lincoln, Masahiro Shimotani Cite as: James R. Lincoln, Masahiro Shimotani. (2009). “Whither the Keiretsu, Japan's Business Networks? How Were They Structured? What Did They Do? Why Are They Gone?” IRLE Working Paper No. 188-09. http://irle.berkeley.edu/workingpapers/188-09.pdf irle.berkeley.edu/workingpapers Institute for Research on Labor and Employment Institute for Research on Labor and Employment Working Paper Series (University of California, Berkeley) Year Paper iirwps-- Whither the Keiretsu, Japan’s Business Networks? How Were They Structured? What Did They Do? Why Are They Gone? James R. Lincoln Masahiro Shimotani University of California, Berkeley Fukui Prefectural University This paper is posted at the eScholarship Repository, University of California. http://repositories.cdlib.org/iir/iirwps/iirwps-188-09 Copyright c 2009 by the authors. WHITHER THE KEIRETSU, JAPAN’S BUSINESS NETWORKS? How were they structured? What did they do? Why are they gone? James R. Lincoln Walter A. Haas School of Business University of California, Berkeley Berkeley, CA 94720 USA ([email protected]) Masahiro Shimotani Faculty of Economics Fukui Prefectural University Fukui City, Japan ([email protected]) 1 INTRODUCTION The title of this volume and the papers that fill it concern business “groups,” a term suggesting an identifiable collection of actors (here, firms) within a clear-cut boundary. The Japanese keiretsu have been described in similar terms, yet compared to business groups in other countries the postwar keiretsu warrant the “group” label least. -

Plastic Manufactures Manufacturer Tradename Material 3M Corp

Plastic Manufactures Manufacturer Tradename Material 3M Corp. Vikuiti PC/PET film 3M Performance Polymers FTPE Fluoroelastomer A. L. Hyde Company Hydlar PA aramid fiber reinforced A. Schulman Formion Ionomer A. Schulman Invision TPO A. Schulman Miraprene TPV A. Schulman Polyaxis Rotational molding compounds A. Schulman Polyfabs ABS A. Schulman Polyflam Flame retardant compounds A. Schulman Polyfort PP, PE, EVA A. Schulman Polyman ABS alloys A. Schulman Polypur PUR A. Schulman Polytrope TPO A. Schulman Polyvin Flexible PVC A. Schulman Schulablend ABS/PA A. Schulman Schuladur PBT A. Schulman Schulaflex Flexible elastomers A. Schulman Schulamid PA 6, PA 66 A. Schulman Schulink HDPE A. Schulman Sunprene PVC elastomer Achilles Corporation Achilles Foamed PS, PUR Aclo Compounders Accucomp Blended compounds Aclo Compounders Accuguard Flame retardant compounds Aclo Compounders Acculoy Alloyed resins Aclo Compounders Accutech Engineering resins Actiplast Acvitron Flexible PVC Addiplast Addilene PP Addiplast Addinyl PA 6, PA 66 Adell Adell Thermoplastic resin Advanced Elastomer Systems Dytron TPE Advanced Elastomer Systems Geolast TPV Advanced Elastomer Systems Santoprene EPTR Advanced Elastomer Systems Trefsin TPE Advanced Elastomer Systems VistaFlex TPO Advanced Elastomer Systems Vyram EPTR Advanced Polymer Alloys LLC DuraGrip Thermoplastic rubber Aiscondel Etinox PVC Akai Plastik Sanayi Ve Ticaret AS Aklamid PA 6, PA 66 Akai Plastik Sanayi Ve Ticaret AS Akmaril ABS Akai Plastik Sanayi Ve Ticaret AS Akron HIPS Albis Albis PA 6, PA 66 Albis Alcom PA 66, POM Albis Cellidor CAB, CP Albis Petlon PBT Albis Tedur PPS Alfagomma S.p.A. Alfater XL TPV Alfaline S.r.l. Alfacarb PC Alfaline S.r.l. Alfanyl PA 6, PA 66 Alfaline S.r.l. -

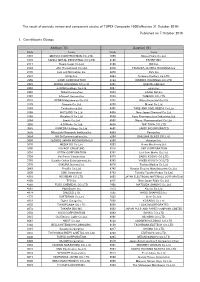

Published on 7 October 2016 1. Constituents Change the Result Of

The result of periodic review and component stocks of TOPIX Composite 1500(effective 31 October 2016) Published on 7 October 2016 1. Constituents Change Addition( 70 ) Deletion( 60 ) Code Issue Code Issue 1810 MATSUI CONSTRUCTION CO.,LTD. 1868 Mitsui Home Co.,Ltd. 1972 SANKO METAL INDUSTRIAL CO.,LTD. 2196 ESCRIT INC. 2117 Nissin Sugar Co.,Ltd. 2198 IKK Inc. 2124 JAC Recruitment Co.,Ltd. 2418 TSUKADA GLOBAL HOLDINGS Inc. 2170 Link and Motivation Inc. 3079 DVx Inc. 2337 Ichigo Inc. 3093 Treasure Factory Co.,LTD. 2359 CORE CORPORATION 3194 KIRINDO HOLDINGS CO.,LTD. 2429 WORLD HOLDINGS CO.,LTD. 3205 DAIDOH LIMITED 2462 J-COM Holdings Co.,Ltd. 3667 enish,inc. 2485 TEAR Corporation 3834 ASAHI Net,Inc. 2492 Infomart Corporation 3946 TOMOKU CO.,LTD. 2915 KENKO Mayonnaise Co.,Ltd. 4221 Okura Industrial Co.,Ltd. 3179 Syuppin Co.,Ltd. 4238 Miraial Co.,Ltd. 3193 Torikizoku co.,ltd. 4331 TAKE AND GIVE. NEEDS Co.,Ltd. 3196 HOTLAND Co.,Ltd. 4406 New Japan Chemical Co.,Ltd. 3199 Watahan & Co.,Ltd. 4538 Fuso Pharmaceutical Industries,Ltd. 3244 Samty Co.,Ltd. 4550 Nissui Pharmaceutical Co.,Ltd. 3250 A.D.Works Co.,Ltd. 4636 T&K TOKA CO.,LTD. 3543 KOMEDA Holdings Co.,Ltd. 4651 SANIX INCORPORATED 3636 Mitsubishi Research Institute,Inc. 4809 Paraca Inc. 3654 HITO-Communications,Inc. 5204 ISHIZUKA GLASS CO.,LTD. 3666 TECNOS JAPAN INCORPORATED 5998 Advanex Inc. 3678 MEDIA DO Co.,Ltd. 6203 Howa Machinery,Ltd. 3688 VOYAGE GROUP,INC. 6319 SNT CORPORATION 3694 OPTiM CORPORATION 6362 Ishii Iron Works Co.,Ltd. 3724 VeriServe Corporation 6373 DAIDO KOGYO CO.,LTD. 3765 GungHo Online Entertainment,Inc. -

2020 Company Overview

2020 company overview Overview Company name Fujita Corporation Headquarters address 4-25-2 Sendagaya, Shibuya-ku Tokyo, 151-8570 Japan (Headquarters address on commercial registry: 4-32-22 Nishi-Shinjuku, Shinjuku-ku, Tokyo) Representative President and CEO Yoji Okumura Established December 1, 1910 Incorporated October 1, 2002 Contractor’s license Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism (Special-29, Special-30) No.19796 Building lots and buildings transaction business license Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism License No. 6348 (4) Capital 14 billion yen Number of employees 3,183 (As of December 31, 2019) Number of licensed Doctorates in engineering, science, and other elds: 38 Professional engineers: 203 employees Registered architects, rst class: 666 Registered supervising engineers of construction work, rst class: 1018 Registered supervising engineers of civil engineering work, rst class: 779 Registered real-estate brokers (certied): 570 Business details 1 Contracting, planning, design, supervision, and consulting services for construction projects (Articles of 2 Research, planning, design, management, and consulting services related to space development, marine develop- Incorporation) ment, community development, urban development, resource development, and environmental improvement 3 Real estate appraisals and business operations related to real estate buying, selling, trading, leasing, and management as well as agent and mediation services 4 Type II nancial instruments business based on the Financial -

Fuji Seal Group Environment Report Vol.7 / New Approach to the Future

Fuji Seal International, INC. ENVIRONMENTAL REPORT Vol. 7 Fuji Seal Group New Approach to the Future in environmental sustainability.both customers and Oursociety’s packages initiatives contribute to R Plus Japan Ltd. - A new joint venture company that will invest in the development of cutting-edge recycling technology for used plastics Fuji Seal Group is proud to announce the establishment of R Plus Japan Ltd., a new joint venture company that will invest in the development of cut- ting-edge recycling technology for used plastics. R Plus Japan (CEO: Mr. Tsunehiko Yokoi, Location: Tokyo, Japan) was established in partnership with Fuji Seal, Inc. and 11 other cross-industry partners within the plastics supply chain in June, 2020. This collaboration aims to find effective solutions to ad- dress plastics waste issues to create a more sustainable society. Member partners include Suntory MONOZUKURI Expert Ltd., TOYOBO Co. Ltd., Rengo Co. Ltd., Toyo Seikan Group Holdings Ltd., J&T Recycling Corporation, Asahi Group Holdings Ltd., Iwatani Corporation, Dai Nippon Printing Co. Ltd., Toppan Printing Co. Ltd., Hokkaiseican Co. Ltd., and Yoshino Kogyosho Co. Ltd.. Our mission statement is “Each day, with renewed commitment, we create new value through packaging.” We are strengthening our ESG initiatives to form a better society and to make the company more sustainable. In par- ticular, we recognize that the environmental problem is an important issue for humanity, and our creativity and efforts should be made to manufac- ture products with environmental aspects in mind. We aim to contribute positively to the environment and society through our products such as like to introduce some of our efforts. -

1 Atb 2016-III Consolidated Business of Fiber & Textile Makers in Japan, April 1, 2019 to March 31, 2020

Consolidated Business of Fiber & Textile Makers in Japan, April 1, 2019 to March 31, 2020 (million yen) Y-o-Y Operating Y-o-Y Y-o-Y Net Sales Net Profits Change (%) Profits Change (%) Change (%) Fiber producers Toray 2,214,633 –7.3 131,186 –7.3 55,725 –29.8 Asahi Kasei 2,151,646 –0.9 177,264 –15.4 103,931 –29.5 Teijin 853,746 –3.9 56,205 –6.3 25,252 –44.0 Kaneka 601,514 –3.1 26,014 –27.8 14,003 –37.0 Toyobo 339,607 0.9 22,794 4.9 13,774 — Unitika 119,537 –7.4 5,467 –32.9 –2,158 — Kuraray(1) 575,807 –4.5 54,173 –17.7 –1,956 — Cotton spinners & textile makers Daiwabo Holdings 944,053 20.2 32,841 44.6 21,178 26.2 Kurabo 142,926 –9.0 4,541 –19.5 3,731 –19.7 Shikibo 38,037 –6.8 1,979 –17.7 983 — Fujibo Holdings 38,701 4.3 4,079 7.9 2,269 –10.6 Omikenshi 9,026 –7.4 –207 — –2,367 — Nitto Boseki 85,722 4.2 8,160 –0.5 5,771 –27.7 Nisshinbo Holdings(2) 509,660 — 6,284 — –6,604 — Textile dyers & processors Seiren 120,258 –2.0 10,502 –0.8 8,551 3.9 Komatsu Matere 36,525 –6.5 1,612 –25.5 1,375 –35.5 Sakai Ovex 27,561 1.1 2,123 4.9 2,313 3.8 Tokai Senko 14,010 –3.4 617 –17.9 –551 — Sotoh 11,219 –0.1 193 –19.1 –97 — Soko Seiren 2,778 –17.7 –245 — –130 — Note: (1) Kuraray's business performance is for the period from January to December 2019. -

Istoxx® Mutb Japan Momentum 300 Index

ISTOXX® MUTB JAPAN MOMENTUM 300 INDEX Components1 Company Supersector Country Weight (%) Z HOLDINGS Technology Japan 0.69 M3 Health Care Japan 0.65 KOEI TECMO HOLDINGS Technology Japan 0.65 MENICON Health Care Japan 0.59 CAPCOM Technology Japan 0.58 FUJITEC Industrial Goods & Services Japan 0.56 Ibiden Co. Ltd. Industrial Goods & Services Japan 0.56 NIPPON PAINT HOLDINGS Chemicals Japan 0.56 RENESAS ELECTRONICS Technology Japan 0.55 JEOL Industrial Goods & Services Japan 0.55 INTERNET INTV.JAPAN Technology Japan 0.53 JSR Corp. Chemicals Japan 0.52 NET ONE SYSTEMS Technology Japan 0.51 Fujitsu Ltd. Technology Japan 0.51 Bank of Kyoto Ltd. Banks Japan 0.51 Hokuhoku Financial Group Inc. Banks Japan 0.51 FUJITSU GENERAL Personal & Household Goods Japan 0.50 Iyo Bank Ltd. Banks Japan 0.50 Kyushu Financial Group Banks Japan 0.50 77 Bank Ltd. Banks Japan 0.49 COCOKARA FINE INC. Retail Japan 0.49 TOSHIBA TEC Industrial Goods & Services Japan 0.48 JCR PHARMACEUTICALS Health Care Japan 0.48 MONOTARO Retail Japan 0.48 COSMOS PHARM. Retail Japan 0.48 Tokyo Electron Ltd. Technology Japan 0.48 Nomura Research Institute Ltd. Technology Japan 0.48 Olympus Corp. Health Care Japan 0.47 SUNDRUG Retail Japan 0.47 Chiba Bank Ltd. Banks Japan 0.47 NEC NETWORKS & SY.INTG. Technology Japan 0.47 Nomura Holdings Inc. Financial Services Japan 0.47 TOKYO OHKA KOGYO Technology Japan 0.47 PENTA-OCEAN CONSTRUCTION Construction & Materials Japan 0.47 FUYO GENERAL LEASE Financial Services Japan 0.46 FUJI Industrial Goods & Services Japan 0.46 Hachijuni Bank Ltd. -

Title the Structural Transformation and Strategic Reorientation Of

The Structural Transformation and Strategic Reorientation of Title Japanese Textile Businesses M.COLPAN, Asli; HIKINO, Takashi; SHIMOTANI, Author(s) Masahiro; YOKOYAMA, Atsushi The Kyoto University Economic Review (2002), 71(1-2): 65- Citation 75 Issue Date 2002-12 URL https://doi.org/10.11179/ker1926.71.65 Right Type Departmental Bulletin Paper Textversion publisher Kyoto University The Structural Transformation and Strategic Reorientation of Japanese Textile Businesses by M. Ash COLPAN* , Takashi HIKINO** , Masahiro SHIMOTANI*** and Atsushi YOKOYAMA **** I Introduction Japan' s textile industlγ , with its inexpensive and high-quality labor, enjoyed a competiュ tive advantage for many years over other countries. As a result of the appreciation of yen as well as the growing competition from emerging economies since the 1970s, however , the Japanese textile industry lost its international competitiveness. Imports began to exceed exports starting in 1986, and Japan became a net importer of textile products. In this period ラthe Plaza Accord of 1985 marked the final transformation of Japan's base of textile businesses into an import indus ・ try. In this historical and economic context, this paper aims to examine the historical and conュ temporary role of the textile industry in the economic development of Japan, and also to provide the basic analysis of the current process of restructuring taking place within the industries. Furュ thermore, the paper in the end explores certain strategic solutions for the survival and transforュ mation of Japanese textile businesses , which are of four folds: (1) an increase in knowledge inュ tensity and the enhancement of high technology manufacturing , (2) the expansion of global manufacturing and marketing operations ラ(3) diversification , particularly for the large enterュ prises, into non-fiber operations , and (4) organizational adjustments through mergers , acquisiュ tions and strategic alliances among the businesses in the textile chain. -

Stoxx® Japan 600 Esg-X Index

STOXX® JAPAN 600 ESG-X INDEX Components1 Company Supersector Country Weight (%) Toyota Motor Corp. Automobiles & Parts Japan 3.87 Sony Corp. Consumer Products & Services Japan 2.55 Softbank Group Corp. Telecommunications Japan 2.44 Keyence Corp. Industrial Goods & Services Japan 1.77 RECRUIT HOLDINGS Industrial Goods & Services Japan 1.54 Mitsubishi UFJ Financial Group Banks Japan 1.48 Shin-Etsu Chemical Co. Ltd. Chemicals Japan 1.36 Nippon Telegraph & Telephone C Telecommunications Japan 1.36 Nintendo Co. Ltd. Consumer Products & Services Japan 1.30 Nidec Corp. Technology Japan 1.30 Fast Retailing Co. Ltd. Retail Japan 1.25 Daikin Industries Ltd. Construction & Materials Japan 1.19 Takeda Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd. Health Care Japan 1.18 Tokyo Electron Ltd. Technology Japan 1.16 Honda Motor Co. Ltd. Automobiles & Parts Japan 1.10 Daiichi Sankyo Co. Ltd. Health Care Japan 1.08 Sumitomo Mitsui Financial Grou Banks Japan 1.04 Murata Manufacturing Co. Ltd. Technology Japan 1.03 KDDI Corp. Telecommunications Japan 1.02 Hitachi Ltd. Industrial Goods & Services Japan 0.92 Itochu Corp. Industrial Goods & Services Japan 0.92 Fanuc Ltd. Industrial Goods & Services Japan 0.90 Hoya Corp. Health Care Japan 0.84 Mitsubishi Corp. Industrial Goods & Services Japan 0.83 Mizuho Financial Group Inc. Banks Japan 0.76 SOFTBANK Telecommunications Japan 0.75 Denso Corp. Automobiles & Parts Japan 0.72 Mitsui & Co. Ltd. Industrial Goods & Services Japan 0.71 Tokio Marine Holdings Inc. Insurance Japan 0.70 Oriental Land Co. Ltd. Travel & Leisure Japan 0.68 SMC Corp. Industrial Goods & Services Japan 0.68 Mitsubishi Electric Corp. Industrial Goods & Services Japan 0.67 Seven & I Holdings Co. -

Accelerate Your Pathway to Partnerships in Asia MARCH 10-11, 2020 • TOKYO, JAPAN

Asia Tokyo International Conference 2020 Accelerate your Pathway to Partnerships in Asia MARCH 10-11, 2020 • TOKYO, JAPAN General Overview • Advisory Committee • Education and Conference Programming • Partnering • Sponsorship Opportunities • #BIOASIA20 • bio.org/asia The BIO Asia International Conference is an exclusive partnering forum that brings together the global biotechnology and pharmaceutical industry to explore licensing and investor engagement in the current Asia-Pacific business and policy environments. Event Attributes and Opportunities • Gain insights into the changes, challenges, and opportunities collaborations and funding opportunities with participating key opinion and policy leaders foresee for the Japanese companies; communicate directly with conference attendees; biotech market. and pre-schedule private, 30 minute One-on-One meetings to be conducted onsite. • Facilitate connections with strategic partners looking to invest, partner, or license in or license out, early to late-stage • Panel discussions will increase your understanding of, programs in your therapeutic area of focus. and interaction with, the Japanese biotech market, the political landscape in Japan, and its impact on this important Opportunity for organizations to deliver company • industry sector. presentations, providing increased visibility in front of a global audience of biotech and pharmaceutical companies, all • Network with government leaders, peers, investors, and interested in cross-border business development alliances and potential partners attending the conference and our exclusive research collaborations. welcome reception. • BIO One-on-One Partnering enables attendees to search • Exclusive sponsorship opportunities to showcase thought company and investor profiles, drug assets, products, leadership, elevate brand identity and maximize partnering and services in the biopharma industry; evaluate potential benefits with an elite audience.