Title the Structural Transformation and Strategic Reorientation Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1332 Nippon Suisan Kaisha, Ltd. 50 1333 Maruha Nichiro Corp. 500 1605 Inpex Corp

Nikkei Stock Average - Par Value (Update:August/1, 2017) Code Company Name Par Value(Yen) 1332 Nippon Suisan Kaisha, Ltd. 50 1333 Maruha Nichiro Corp. 500 1605 Inpex Corp. 125 1721 Comsys Holdings Corp. 50 1801 Taisei Corp. 50 1802 Obayashi Corp. 50 1803 Shimizu Corp. 50 1808 Haseko Corp. 250 1812 Kajima Corp. 50 1925 Daiwa House Industry Co., Ltd. 50 1928 Sekisui House, Ltd. 50 1963 JGC Corp. 50 2002 Nisshin Seifun Group Inc. 50 2269 Meiji Holdings Co., Ltd. 250 2282 Nh Foods Ltd. 50 2432 DeNA Co., Ltd. 500/3 2501 Sapporo Holdings Ltd. 250 2502 Asahi Group Holdings, Ltd. 50 2503 Kirin Holdings Co., Ltd. 50 2531 Takara Holdings Inc. 50 2768 Sojitz Corp. 500 2801 Kikkoman Corp. 50 2802 Ajinomoto Co., Inc. 50 2871 Nichirei Corp. 100 2914 Japan Tobacco Inc. 50 3086 J.Front Retailing Co., Ltd. 100 3099 Isetan Mitsukoshi Holdings Ltd. 50 3101 Toyobo Co., Ltd. 50 3103 Unitika Ltd. 50 3105 Nisshinbo Holdings Inc. 50 3289 Tokyu Fudosan Holdings Corp. 50 3382 Seven & i Holdings Co., Ltd. 50 3401 Teijin Ltd. 250 3402 Toray Industries, Inc. 50 3405 Kuraray Co., Ltd. 50 3407 Asahi Kasei Corp. 50 3436 SUMCO Corp. 500 3861 Oji Holdings Corp. 50 3863 Nippon Paper Industries Co., Ltd. 500 3865 Hokuetsu Kishu Paper Co., Ltd. 50 4004 Showa Denko K.K. 500 4005 Sumitomo Chemical Co., Ltd. 50 4021 Nissan Chemical Industries, Ltd. 50 4042 Tosoh Corp. 50 4043 Tokuyama Corp. 50 WF-101-E-20170803 Copyright © Nikkei Inc. All rights reserved. 1/5 Nikkei Stock Average - Par Value (Update:August/1, 2017) Code Company Name Par Value(Yen) 4061 Denka Co., Ltd. -

Anellotech Plas-Tcat Funding from R Plus Japan Press Release June 30

Anellotech Secures Funds to Develop Innovative Plas-TCatTM Plastics Recycling Technology from R Plus Japan, a New Joint Venture Company launched by 12 Cross-Industry Partners within the Japanese Plastic Supply Chain Pearl River, NY, USA, (June 30, 2020) —Sustainable technology company Anellotech has announced that R Plus Japan Ltd., a new joint venture company, will invest in the development of Anellotech’s cutting-edge Plas-TCatTM technology for recycling used plastics. R Plus Japan was established by 12 cross-industry partners within the Japanese plastics supply chain. Member partners include Suntory MONOZUKURI Expert Ltd. (SME, a subsidiary of Suntory Holdings Ltd.), TOYOBO Co. Ltd., Rengo Co. Ltd., Toyo Seikan Group Holdings Ltd., J&T Recycling Corporation, Asahi Group Holdings Ltd., Iwatani Corporation, Dai Nippon Printing Co. Ltd., Toppan Printing Co. Ltd., Fuji Seal International Inc., Hokkaican Co. Ltd., Yoshino Kogyosho Co. Ltd.. Many plastic packaging materials are unable to be recycled and are instead thrown away after a single use, often landfilled, incinerated, or littered, polluting land and oceans. Unlike the existing multi-step processes which first liquefy plastic waste back into low value “synthetic oil” intermediate products, Anellotech’s Plas- TCat chemical recycling technology uses a one-step thermal-catalytic process to convert single-use plastics directly into basic chemicals such as benzene, toluene, xylenes (BTX), ethylene, and propylene, which can then be used to make new plastics. The technology’s process efficiency has the potential to significantly reduce CO2 emissions and energy consumption. Once utilized across the industry, this technology will be able to more efficiently recycle single-use plastic, one of the world’s most urgent challenges. -

Whither the Keiretsu, Japan's Business Networks? How Were They Structured? What Did They Do? Why Are They Gone?

IRLE IRLE WORKING PAPER #188-09 September 2009 Whither the Keiretsu, Japan's Business Networks? How Were They Structured? What Did They Do? Why Are They Gone? James R. Lincoln, Masahiro Shimotani Cite as: James R. Lincoln, Masahiro Shimotani. (2009). “Whither the Keiretsu, Japan's Business Networks? How Were They Structured? What Did They Do? Why Are They Gone?” IRLE Working Paper No. 188-09. http://irle.berkeley.edu/workingpapers/188-09.pdf irle.berkeley.edu/workingpapers Institute for Research on Labor and Employment Institute for Research on Labor and Employment Working Paper Series (University of California, Berkeley) Year Paper iirwps-- Whither the Keiretsu, Japan’s Business Networks? How Were They Structured? What Did They Do? Why Are They Gone? James R. Lincoln Masahiro Shimotani University of California, Berkeley Fukui Prefectural University This paper is posted at the eScholarship Repository, University of California. http://repositories.cdlib.org/iir/iirwps/iirwps-188-09 Copyright c 2009 by the authors. WHITHER THE KEIRETSU, JAPAN’S BUSINESS NETWORKS? How were they structured? What did they do? Why are they gone? James R. Lincoln Walter A. Haas School of Business University of California, Berkeley Berkeley, CA 94720 USA ([email protected]) Masahiro Shimotani Faculty of Economics Fukui Prefectural University Fukui City, Japan ([email protected]) 1 INTRODUCTION The title of this volume and the papers that fill it concern business “groups,” a term suggesting an identifiable collection of actors (here, firms) within a clear-cut boundary. The Japanese keiretsu have been described in similar terms, yet compared to business groups in other countries the postwar keiretsu warrant the “group” label least. -

Plastic Manufactures Manufacturer Tradename Material 3M Corp

Plastic Manufactures Manufacturer Tradename Material 3M Corp. Vikuiti PC/PET film 3M Performance Polymers FTPE Fluoroelastomer A. L. Hyde Company Hydlar PA aramid fiber reinforced A. Schulman Formion Ionomer A. Schulman Invision TPO A. Schulman Miraprene TPV A. Schulman Polyaxis Rotational molding compounds A. Schulman Polyfabs ABS A. Schulman Polyflam Flame retardant compounds A. Schulman Polyfort PP, PE, EVA A. Schulman Polyman ABS alloys A. Schulman Polypur PUR A. Schulman Polytrope TPO A. Schulman Polyvin Flexible PVC A. Schulman Schulablend ABS/PA A. Schulman Schuladur PBT A. Schulman Schulaflex Flexible elastomers A. Schulman Schulamid PA 6, PA 66 A. Schulman Schulink HDPE A. Schulman Sunprene PVC elastomer Achilles Corporation Achilles Foamed PS, PUR Aclo Compounders Accucomp Blended compounds Aclo Compounders Accuguard Flame retardant compounds Aclo Compounders Acculoy Alloyed resins Aclo Compounders Accutech Engineering resins Actiplast Acvitron Flexible PVC Addiplast Addilene PP Addiplast Addinyl PA 6, PA 66 Adell Adell Thermoplastic resin Advanced Elastomer Systems Dytron TPE Advanced Elastomer Systems Geolast TPV Advanced Elastomer Systems Santoprene EPTR Advanced Elastomer Systems Trefsin TPE Advanced Elastomer Systems VistaFlex TPO Advanced Elastomer Systems Vyram EPTR Advanced Polymer Alloys LLC DuraGrip Thermoplastic rubber Aiscondel Etinox PVC Akai Plastik Sanayi Ve Ticaret AS Aklamid PA 6, PA 66 Akai Plastik Sanayi Ve Ticaret AS Akmaril ABS Akai Plastik Sanayi Ve Ticaret AS Akron HIPS Albis Albis PA 6, PA 66 Albis Alcom PA 66, POM Albis Cellidor CAB, CP Albis Petlon PBT Albis Tedur PPS Alfagomma S.p.A. Alfater XL TPV Alfaline S.r.l. Alfacarb PC Alfaline S.r.l. Alfanyl PA 6, PA 66 Alfaline S.r.l. -

2020 Company Overview

2020 company overview Overview Company name Fujita Corporation Headquarters address 4-25-2 Sendagaya, Shibuya-ku Tokyo, 151-8570 Japan (Headquarters address on commercial registry: 4-32-22 Nishi-Shinjuku, Shinjuku-ku, Tokyo) Representative President and CEO Yoji Okumura Established December 1, 1910 Incorporated October 1, 2002 Contractor’s license Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism (Special-29, Special-30) No.19796 Building lots and buildings transaction business license Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism License No. 6348 (4) Capital 14 billion yen Number of employees 3,183 (As of December 31, 2019) Number of licensed Doctorates in engineering, science, and other elds: 38 Professional engineers: 203 employees Registered architects, rst class: 666 Registered supervising engineers of construction work, rst class: 1018 Registered supervising engineers of civil engineering work, rst class: 779 Registered real-estate brokers (certied): 570 Business details 1 Contracting, planning, design, supervision, and consulting services for construction projects (Articles of 2 Research, planning, design, management, and consulting services related to space development, marine develop- Incorporation) ment, community development, urban development, resource development, and environmental improvement 3 Real estate appraisals and business operations related to real estate buying, selling, trading, leasing, and management as well as agent and mediation services 4 Type II nancial instruments business based on the Financial -

Fuji Seal Group Environment Report Vol.7 / New Approach to the Future

Fuji Seal International, INC. ENVIRONMENTAL REPORT Vol. 7 Fuji Seal Group New Approach to the Future in environmental sustainability.both customers and Oursociety’s packages initiatives contribute to R Plus Japan Ltd. - A new joint venture company that will invest in the development of cutting-edge recycling technology for used plastics Fuji Seal Group is proud to announce the establishment of R Plus Japan Ltd., a new joint venture company that will invest in the development of cut- ting-edge recycling technology for used plastics. R Plus Japan (CEO: Mr. Tsunehiko Yokoi, Location: Tokyo, Japan) was established in partnership with Fuji Seal, Inc. and 11 other cross-industry partners within the plastics supply chain in June, 2020. This collaboration aims to find effective solutions to ad- dress plastics waste issues to create a more sustainable society. Member partners include Suntory MONOZUKURI Expert Ltd., TOYOBO Co. Ltd., Rengo Co. Ltd., Toyo Seikan Group Holdings Ltd., J&T Recycling Corporation, Asahi Group Holdings Ltd., Iwatani Corporation, Dai Nippon Printing Co. Ltd., Toppan Printing Co. Ltd., Hokkaiseican Co. Ltd., and Yoshino Kogyosho Co. Ltd.. Our mission statement is “Each day, with renewed commitment, we create new value through packaging.” We are strengthening our ESG initiatives to form a better society and to make the company more sustainable. In par- ticular, we recognize that the environmental problem is an important issue for humanity, and our creativity and efforts should be made to manufac- ture products with environmental aspects in mind. We aim to contribute positively to the environment and society through our products such as like to introduce some of our efforts. -

English Brochure

FREE OF CHARGE: EXHIBITION 1. Enjoy our free voice guide machine! (English, Chinese, Korean and Japanese) Prologue Theater (13 minutes English video) No reservation is needed. “The origin of the entrepreneurship of Osaka” 大阪企業家ミュージアム 2. Locker Refundable locker is available in front of the Under the shogunate government, why did so many entrepreneurs leave reception (JPY100). their hometown to look for a business chance in Osaka? Let’s look back from 3. Tour Guide is available per group for over 10 people; the end of the 16c. Hideyoshi Toyotomi built Osaka castle up to the end of reservation is needed. the 19c., when was the last stage of Edo era, to find out how Osaka became NOTICE the origin of the entrepreneurship. NO PHOTOGRAPHY, EATING and SMOKING inside the museum. Main exhibit area Block 1 Thank you for your cooperation! Meiji Restoration to the end of Meiji era 1868-1911 1 BUILDING THE ECONOMIC INFRASTRUCTURE OF MODERN OSAKA OPEN HOURS GODAI Tomoatsu Osaka Chamber of Commerce and Industry 10:00 – 17:00 Tue, Thu, Fri, Sat MATSUMOTO Jutaro Mizuho Financial Group. Inc. 10:00 – 20:00 Wed FUJITA Denzaburo Dowa Holdings Co., Ltd. Admission until 30 minutes prior to closing time. HIROSE Saihei Sumitomo Group CLOSED on Sun, Mon, National holidays and NAKAHASHI Tokugoro Mitsui O.S.K.Lines Ltd. 8/14 - 17, 12/26 - 1/4 2 MAKING OSAKA THE MANCHESTER OF THE EAST ADMISSION YAMANOBE Takeo Toyobo Co., Ltd. Aiming to develop the next generation of human Adult:JPY 300 Student:JPY 100 KIKUCHI Kyozo Unitika Ltd. resource, the Osaka Chamber of Commerce and Industry Under 6 years:Free MUTO Sanji KRACIE Holdings established Osaka Entrepreneurial Museum in 2001. -

Comprehensive List of Pharmaceuticals-Related Projects

Pharmaceutical and R&D Facilities Facility Type Photo Client Location Completion Scope Wakayama/ Solid Dosage TAMURA PHARMACEUTICAL CO.,LTD. 2019 EPCV Japan Gunma/ Bio Bulk DAIICHI SANKYO CHEMICAL PHARMA CO., LTD. 2019 EPCV Japan Hyogo/ R&D Center KANAE CO.,LTD. 2019 EPC Japan API undisclosed Tohoku/Japan 2017 EPCV R&D Center JSR Corporation Tokyo/Japan 2017 EPCV API undisclosed Kitakanto/Japan 2017 EPCV Yamaguchi/ R&D Center TEIJIN PHARMA LIMITED 2015 EPCV Japan Medical Device Menicon Co., Ltd. Chubu/Japan 2014 EPCV Fukushima/ R&D Center SANWA KAGAKU KENKYUSHO CO., LTD. 2014 EPCV Japan Yamaguchi/ Medical Device Terumo Yamaguchi Corporation 2014 E+ES Japan TOYAMA CHEMICAL CO., LTD. Toyama/ Parenteral 2013 EPCV (Current name:FUJIFILM Toyama Chemical Co., Ltd.) Japan Astellas Pharma Inc. Aichi/ Bio Bulk 2013 EPCV (Current name:Micro Biopharm Japan Co.,Ltd.) Japan Kanagawa/ R&D Center Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma Corporation 2011 EPC Japan Hiroshima/ R&D Center YASUHARA CHEMICAL CO., LTD. 2010 EPC Japan Fukushima/ API TOA EIYO LTD. 2009 EPCV Japan Gunma/ R&D Center SANDEN HOLDINGS CORPORATION 2008 EPC Japan Hyogo/ Packaging KANAE CO., LTD. 2008 EPCV Japan ASAHI GLASS CO., LTD. Chiba/ Bio Bulk 2008 EPCV (Current name:AGC Inc.) Japan 1 / 3 Iwate/ Aseptic API Shionogi & Co., Ltd. 2007 EPCV Japan Mie/ Solid Dosage Sumitomo Dainippon Pharma Co., Ltd. 2007 EPCV Japan Saitama/ Nutrition/Liquid Taisho Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. 2007 EPCV Japan Kaketsuken Kumamoto/ Vaccine (The Chemo-sero-therapeutic Research Institute) 2006 EPCV Japan (Current name:KM Biologics Co., Ltd.) Niigata/ Vaccine Denka Seiken Co., Ltd. 2006 EPCV Japan Shizuoka/ Bio Bulk Yamaha Motor Co., Ltd. -

Notice of Share Transfer Agreement Regarding Sale of Our Consolidated Subsidiaries of Film Business (The Transfer of Our Consolidated Subsidiaries)

May 22, 2019 To whom it may concern Company: Teijin Limited Stock code: 3401 (First Section, Tokyo Stock Exchange) Representative: Jun Suzuki, President and CEO Contact: Tomoko Torii, General Manager, Investor Relations Department Tel: +81-3-3506-4395 Notice of Share Transfer Agreement Regarding Sale of our Consolidated Subsidiaries of Film Business (the Transfer of our Consolidated Subsidiaries) Teijin Limited (“the Company”) has announced that we have decided to sell our entire stake in consolidated subsidiaries of Teijin Film Solutions Limited (“TFS”) and P.T. Indonesia Teijin Film Solutions (“ITFS”), that operate polyester film businesses in Japan and Indonesia respectively, to Toyobo Co., Ltd. (“Toyobo”) and signed a share transfer agreement today. 1. About contents of transfer The Teijin Group has taken various measures such as consolidating Japanese production bases in the Utsunomiya plant in 2016 in order to strengthen the competitiveness of the polyester film business. In addition, the Company had acquired the interests owned by E.I. du Pont de Nemours and Company (“DuPont”) in the joint ventures in Japan and Indonesia and converted those joint ventures into wholly owned subsidiaries, in order to improve flexibility in the business operations and speed up the decision-making processes. As a result, the polyester film profitability was improved to a certain level. However, this decision was made considering further growth of TFS and ITFS and the optimal allocation of the Teijin Group's management resources. Toyobo positions the film business as a growth area and is promoting the expansion of the business. By implementing this share acquisition, Toyobo thinks that the film business would grow significantly through TFS's high development capabilities, the integration of a broad customer network and the strengthening of production systems including ITFS. -

Notice of Share Transfer Agreement Regarding Sale of Our Consolidated Subsidiaries of Film Business (The Transfer of Our Consolidated Subsidiaries)

May 22, 2019 To whom it may concern Company: Teijin Limited Stock code: 3401 (First Section, Tokyo Stock Exchange) Representative: Jun Suzuki, President and CEO Contact: Tomoko Torii, General Manager, Investor Relations Department Tel: +81-3-3506-4395 Notice of Share Transfer Agreement Regarding Sale of our Consolidated Subsidiaries of Film Business (the Transfer of our Consolidated Subsidiaries) Teijin Limited (“the Company”) has announced that we have decided to sell our entire stake in consolidated subsidiaries of Teijin Film Solutions Limited (“TFS”) and P.T. Indonesia Teijin Film Solutions (“ITFS”), that operate polyester film businesses in Japan and Indonesia respectively, to Toyobo Co., Ltd. (“Toyobo”) and signed a share transfer agreement today. 1. About contents of transfer The Teijin Group has taken various measures such as consolidating Japanese production bases in the Utsunomiya plant in 2016 in order to strengthen the competitiveness of the polyester film business. In addition, the Company had acquired the interests owned by E.I. du Pont de Nemours and Company (“DuPont”) in the joint ventures in Japan and Indonesia and converted those joint ventures into wholly owned subsidiaries, in order to improve flexibility in the business operations and speed up the decision-making processes. As a result, the polyester film profitability was improved to a certain level. However, this decision was made considering further growth of TFS and ITFS and the optimal allocation of the Teijin Group's management resources. Toyobo positions the film business as a growth area and is promoting the expansion of the business. By implementing this share acquisition, Toyobo thinks that the film business would grow significantly through TFS's high development capabilities, the integration of a broad customer network and the strengthening of production systems including ITFS. -

Published on 7 October 2015 1. Constituents Change the Result Of

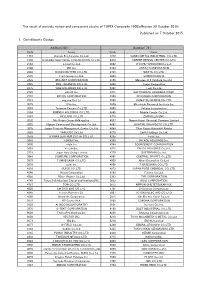

The result of periodic review and component stocks of TOPIX Composite 1500(effective 30 October 2015) Published on 7 October 2015 1. Constituents Change Addition( 80 ) Deletion( 72 ) Code Issue Code Issue 1712 Daiseki Eco.Solution Co.,Ltd. 1972 SANKO METAL INDUSTRIAL CO.,LTD. 1930 HOKURIKU ELECTRICAL CONSTRUCTION CO.,LTD. 2410 CAREER DESIGN CENTER CO.,LTD. 2183 Linical Co.,Ltd. 2692 ITOCHU-SHOKUHIN Co.,Ltd. 2198 IKK Inc. 2733 ARATA CORPORATION 2266 ROKKO BUTTER CO.,LTD. 2735 WATTS CO.,LTD. 2372 I'rom Group Co.,Ltd. 3004 SHINYEI KAISHA 2428 WELLNET CORPORATION 3159 Maruzen CHI Holdings Co.,Ltd. 2445 SRG TAKAMIYA CO.,LTD. 3204 Toabo Corporation 2475 WDB HOLDINGS CO.,LTD. 3361 Toell Co.,Ltd. 2729 JALUX Inc. 3371 SOFTCREATE HOLDINGS CORP. 2767 FIELDS CORPORATION 3396 FELISSIMO CORPORATION 2931 euglena Co.,Ltd. 3580 KOMATSU SEIREN CO.,LTD. 3079 DVx Inc. 3636 Mitsubishi Research Institute,Inc. 3093 Treasure Factory Co.,LTD. 3639 Voltage Incorporation 3194 KIRINDO HOLDINGS CO.,LTD. 3669 Mobile Create Co.,Ltd. 3197 SKYLARK CO.,LTD 3770 ZAPPALLAS,INC. 3232 Mie Kotsu Group Holdings,Inc. 4007 Nippon Kasei Chemical Company Limited 3252 Nippon Commercial Development Co.,Ltd. 4097 KOATSU GAS KOGYO CO.,LTD. 3276 Japan Property Management Center Co.,Ltd. 4098 Titan Kogyo Kabushiki Kaisha 3385 YAKUODO.Co.,Ltd. 4275 Carlit Holdings Co.,Ltd. 3553 KYOWA LEATHER CLOTH CO.,LTD. 4295 Faith, Inc. 3649 FINDEX Inc. 4326 INTAGE HOLDINGS Inc. 3660 istyle Inc. 4344 SOURCENEXT CORPORATION 3681 V-cube,Inc. 4671 FALCO HOLDINGS Co.,Ltd. 3751 Japan Asia Group Limited 4779 SOFTBRAIN Co.,Ltd. 3844 COMTURE CORPORATION 4801 CENTRAL SPORTS Co.,LTD. -

Diversified Expansion and Different Business Models in the Japanese Textile Industry

Volume 3, Issue 4, Winter 2004 DIVERSIFIED EXPANSION AND DIFFERENT BUSINESS MODELS IN THE JAPANESE TEXTILE INDUSTRY ASLI M. COLPAN Kyoto Institute of Technology, Graduate School of Advanced Fibro-science and Kyoto University, Graduate School of Economics ABSTRACT Diversification into non-textile activities became the major instrument for Japan’s large textile enterprises which confronted the maturing state of their original businesses. Diversification strategies that companies adopted exhibited the different directions in their basic investment patterns. The present research confirms that dissimilar technological resource and capability endownments have decisive impacts on the contrasting long-term growth patterns of the companies. The timing of new market entry is also endogenous to the firm resources and capabilities. While firms adapt to the changing environments, diversification can thus be a very much path-dependent process. Keywords: textile industry, Japan, technological resources and capabilities, diversification strategy 1. Introduction on the basic directions of the diversification strategies in the Japanese textile industry. Diversification into non-textile product It thus explores the diversification patterns markets has been the primary strategy for of the leading companies’ and in particular reorganization adapted by the large analyzes the effects of their dissimilar enterprises in the Japanese textile industry.1 technological resources and capabilities on This was because restructuring within textile the different paths of diversification. businesses has not yielded the long-term solution to bring the satisfactory financial For the purposes of this analysis, the outcomes. As a result, the average textile paper uses internal resource-base theories of sales of the largest firms in the Japanese the firm (Penrose, 1959; Nelson and Winter, textile industry have declined from an 1982), which suggests that firms shall average of ninety percent in 1970 to around exploit their resources and capabilities to only forty percent in the present day.