The Role of Ownership and Governance in Bank Risk And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Banks List (May 2011)

LIST OF BANKS AS COMPILED BY THE FSA ON 31 MAY 2011 This list of banks is intended to be used solely as a guide. The FSA does not warrant, nor accept any responsibility for the accuracy or completeness of the list or for any loss which may arise from reliance by any person on information in the list. (Amendments to the List of Banks since 30 April 2011 can be found on page 6) Banks incorporated in the United Kingdom Abbey National Treasury Services plc DB UK Bank Limited ABC International Bank plc Dunbar Bank plc Access Bank UK Limited, The Duncan Lawrie Ltd Adam & Company plc Ahli United Bank (UK) plc EFG Private Bank Ltd Airdrie Savings Bank Egg Banking plc Aldermore Bank Plc European Islamic Investment Bank Plc Alliance & Leicester plc Europe Arab Bank Plc Alliance Trust Savings Ltd Allied Bank Philippines (UK) plc FBN Bank (UK) Ltd Allied Irish Bank (GB)/First Trust Bank - (AIB Group (UK) plc) FCE Bank plc Alpha Bank London Ltd FIBI Bank (UK) plc AMC Bank Ltd Anglo-Romanian Bank Ltd Gatehouse Bank plc Ansbacher & Co Ltd Ghana International Bank plc ANZ Bank (Europe) Ltd Goldman Sachs International Bank Arbuthnot Latham & Co, Ltd Guaranty Trust Bank (UK) Limited Gulf International Bank (UK) Ltd Banc of America Securities Ltd Bank Leumi (UK) plc Habib Allied International Bank plc Bank Mandiri (Europe) Ltd Habibsons Bank Ltd Bank of Beirut (UK) Ltd Hampshire Trust plc Bank of Ceylon (UK) Ltd Harrods Bank Ltd Bank of China (UK) Limited Havin Bank Ltd Bank of Ireland (UK) Plc HFC Bank Ltd Bank of London and The Middle East plc HSBC Bank -

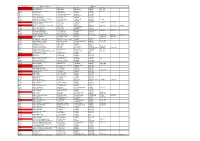

Reference Banks / Finance Address

Reference Banks / Finance Address B/F2 Abbey National Plc Abbey House Baker Street LONDON NW1 6XL B/F262 Abbey National Plc Abbey House Baker Street LONDON NW1 6XL B/F57 Abbey National Treasury Services Abbey House Baker Street LONDON NW1 6XL B/F168 ABN Amro Bank 199 Bishopsgate LONDON EC2M 3TY B/F331 ABSA Bank Ltd 52/54 Gracechurch Street LONDON EC3V 0EH B/F175 Adam & Company Plc 22 Charlotte Square EDINBURGH EH2 4DF B/F313 Adam & Company Plc 42 Pall Mall LONDON SW1Y 5JG B/F263 Afghan National Credit & Finance Ltd New Roman House 10 East Road LONDON N1 6AD B/F180 African Continental Bank Plc 24/28 Moorgate LONDON EC2R 6DJ B/F289 Agricultural Mortgage Corporation (AMC) AMC House Chantry Street ANDOVER Hampshire SP10 1DE B/F147 AIB Capital Markets Plc 12 Old Jewry LONDON EC2 B/F290 Alliance & Leicester Commercial Lending Girobank Bootle Centre Bridal Road BOOTLE Merseyside GIR 0AA B/F67 Alliance & Leicester Plc Carlton Park NARBOROUGH LE9 5XX B/F264 Alliance & Leicester plc 49 Park Lane LONDON W1Y 4EQ B/F110 Alliance Trust Savings Ltd PO Box 164 Meadow House 64 Reform Street DUNDEE DD1 9YP B/F32 Allied Bank of Pakistan Ltd 62-63 Mark Lane LONDON EC3R 7NE B/F134 Allied Bank Philippines (UK) plc 114 Rochester Row LONDON SW1P B/F291 Allied Irish Bank Plc Commercial Banking Bankcentre Belmont Road UXBRIDGE Middlesex UB8 1SA B/F8 Amber Homeloans Ltd 1 Providence Place SKIPTON North Yorks BD23 2HL B/F59 AMC Bank Ltd AMC House Chantry Street ANDOVER SP10 1DD B/F345 American Express Bank Ltd 60 Buckingham Palace Road LONDON SW1 W B/F84 Anglo Irish -

Wealth Management & Private Banking

A Meeting of Minds: Wealth Management & Private Banking Thursday 17 November 2016, The Berkeley Hotel, London, SW1 Participant List Sponsors BUSINESS STRATEGY Affinity Private Wealth - Managing Director Bordier & Cie - Chief Executive Officer C & D Partnerships - Managing Partner C Hoare & Co - Head of Front Office, Banking C Hoare & Co - Head of Wealth Front Office Canaccord Genuity Wealth Management - Chief Executive Officer Coombe Advisors Ltd - Managing Director Credit Suisse Private Bank - Chief Operating Officer Credo Group UK Ltd - Chief Executive Officer Deutsche Bank Wealth Management - Managing Director, Global Business Risk Manager Duncan Lawrie Private Banking - Chairman EFG Private Bank Ltd - Head of Private Banking Goldman Sachs - Chief Supervisory Officer Heartwood Wealth Management - Chief Executive Officer HSBC Bank Plc - EMEA Head of RegTech HSBC Bank Plc - Chief of Staff, Corporate and Institutional Digital J.P. Morgan Private Bank - Associate General Counsel Kleinwort Benson - Managing Director, Head of Private Banking Lincoln Private Investment Office - Managing Partner London & Capital - Chief Operating Officer Mirabaud & Cie SA - Co-Head of Private Wealth Management Owl Private Office - Director and Co-Founder Pictet & Cie (Europe) SA - Chief Operating Officer This list is copyright of the Owen James Group and its contents must be kept confidential and may not be passed to any third party for any purpose Santander Wealth Management - Wealth Management Director & Managing Director - Cater -

The Ritz London, 16Th November 2016 by Invitation Only Confidential – Not for Distribution

® The Ritz London, 16th November 2016 By Invitation Only The AI Finance Summit is the world’s first and only high-level conference exploring the impact of Artificial Intelligence on the financial services industry. The invitation-only event, brings together CxOs from the world’s leading banks, insurance companies, asset management organisations, brokers. The event takes place at London’s most prestigious address, The Ritz, on the 16th of November and features world-class speakers presenting exclusive case studies shedding light into how the 4th industrial revolution will affect specifically affect the financial services industry. DRAFT AGENDA 16tH November 2016, The Ritz London 08:30 Registration, Breakfast refreshments & Networking 09:15 A welcome unlike any other… and Chair’s Opening Remarks 09:20 State of Play opening keynote: the 4th industrial revolution in financial services Where are financial services currently at with artificial intelligence, what technologies in particular are being used, how quickly is it being adopted, and what areas are leading the adoption of new intelligent technologies? These are are some of the pivotal questions answered in the scene-setting opening keynote to the AI Finance Summit. 09:45 Introducing a new era of risk management in investment banking The use of artificial intelligence within the world of investment banking is a phenomenon which is going to propel the industry in more ways than one. This talk will discuss how the advent of AI technologies, focusing on machine learning and cognitive computing, will drastically enhance risk management processes and achieve levels of accuracy previously unseen in the industry 10:10 Customer Experience/ Relations Management through AI platforms AI is revolutionizing customer service across every industry, with financial services already a pioneer in adoption. -

Bank of England List of Banks

LIST OF BANKS AS COMPILED BY THE BANK OF ENGLAND AS AT 31 October 2017 (Amendments to the List of Banks since 30 September 2017 can be found on page 5) Banks incorporated in the United Kingdom Abbey National Treasury Services Plc DB UK Bank Limited ABC International Bank Plc Diamond Bank (UK) Plc Access Bank UK Limited, The Duncan Lawrie Limited (Applied to cancel) Adam & Company Plc ADIB (UK) Ltd EFG Private Bank Limited Agricultural Bank of China (UK) Limited Europe Arab Bank plc Ahli United Bank (UK) PLC AIB Group (UK) Plc FBN Bank (UK) Ltd Airdrie Savings Bank FCE Bank Plc Al Rayan Bank PLC FCMB Bank (UK) Limited Aldermore Bank Plc Alliance Trust Savings Limited Gatehouse Bank Plc Alpha Bank London Limited Ghana International Bank Plc ANZ Bank (Europe) Limited Goldman Sachs International Bank Arbuthnot Latham & Co Limited Guaranty Trust Bank (UK) Limited Atom Bank PLC Gulf International Bank (UK) Limited Axis Bank UK Limited Habib Bank Zurich Plc Bank and Clients PLC Habibsons Bank Limited Bank Leumi (UK) plc Hampden & Co Plc Bank Mandiri (Europe) Limited Hampshire Trust Bank Plc Bank Of America Merrill Lynch International Limited Harrods Bank Ltd Bank of Beirut (UK) Ltd Havin Bank Ltd Bank of Ceylon (UK) Ltd HSBC Bank Plc Bank of China (UK) Ltd HSBC Private Bank (UK) Limited Bank of Cyprus UK Limited HSBC Trust Company (UK) Ltd Bank of Ireland (UK) Plc HSBC UK RFB Limited Bank of London and The Middle East plc Bank of New York Mellon (International) Limited, The ICBC (London) plc Bank of Scotland plc ICBC Standard Bank Plc Bank of the Philippine Islands (Europe) PLC ICICI Bank UK Plc Bank Saderat Plc Investec Bank PLC Bank Sepah International Plc Itau BBA International PLC Barclays Bank Plc Barclays Bank UK PLC J.P. -

The London Gazette, Brd April 1980

5174 THE LONDON GAZETTE, BRD APRIL 1980 Hill Samuel & Co. Ltd. State Bank of India C. Hoare & Co. The Sumitomo Bank, Ltd. The Hokkaido Takushoku Bank, Ltd. The Sumitomo Trust and Bank Company Ltd. The Hongkong and Shanghai Banking Corporation Swiss Bank Corporation Syndicate Bank The Industrial Bank of Japan, Ltd. International Commercial Bank Ltd. The Taiyo Kobe Bank Ltd. International Energy Bank Ltd. Texas Commerce Bank N.A. International Westminster Bank Ltd. The Tokai Bank, Ltd. Investitions - und Handels - Bank A.G. The Toronto-Dominion Bank Irving Trust Company Trade Development Bank Italian International Bank Ltd. Ulster Bank Ltd. Jessel, Toynbee & Co., Ltd. Union Bank of Switzerland Johnson Matthey Bankers Ltd. The Union Discount Company of London Ltd. Leopold Joseph & Sons Ltd. United Bank Ltd. The United Bank of Kuwait Ltd. Keyser Ullmann Ltd. United California Bank King & Shaxson Ltd. United Commercial Bank Kleinwort, Benson Ltd. United Overseas Bank Ltd. Korea Exchange Bank The Kyowa Bank, Ltd. S. G. Warburg & Co. Ltd. Westdeutsche Landesbank Girozentrale Lazard Brothers & Co., Ltd. Williams & Glyn's Bank Ltd. Libra Bank Ltd. Lloyds Bank Ltd. The Yasuda Trust and Banking Co., Ltd. Lloyds Bank International Ltd. Yorkshire Bank Ltd. London & Continental Bankers Ltd. The Long-Term Credit Bank of Japan, Ltd. Zivnostenska" Banka National Corporation Malayan Banking Berhad 2 Licensed Deposit-taking Institutions Manufacturers Hanover Ltd. Manufacturers Hanover Trust Company The Alliance Trust Co. Ltd. Marine Midland Bank N.A. Mellon Bank, N.A. Bank of Europe Ltd. Merrill Lynch International Bank Ltd. Barclays Bank UK Ltd. Midland Bank Ltd. Bowmaker Ltd. Midland and International Banks Ltd. -

Third Party Platforms, Wraps and Investment Managers & Stockbrokers

THIRD PARTY PLATFORMS, WRAPS AND INVESTMENT MANAGERS & STOCKBROKERS The following sets out the Platforms, Wraps, Investment Managers and Stockbrokers who have agreed to James Hay Partnership's terms and conditions. If an Investment Manager or Stockbroker that you would like to use is not on this list, please contact us and we will liaise with the third party to find out if they are able to meet our requirements with a view to including them on this list. Please note: We do not carry out due diligence checks and will not be held liable for their or their custodians’ actions. You should satisfy yourself of the soundness and quality of any third party being appointed. PLATFORMS AND WRAPS Ascentric Openwork Succession INVESTMENT MANAGERS AND STOCKBROKERS Adam & Company Coutts & Co ADM Investor Services Credo Capital Amundi (UK) Limited Cunningham Coates Ltd Arbuthnot Latham & Co Dalton Strategic Partnership LLP Aubrey Capital Management Daniel Stewart & Company Bank Hapoalim Danske Bank Bank of Scotland Portfolio Management Service De Brae Barclays Private Bank Dowgate Capital Stockbrokers Barclays Stockbrokers Duncan Lawrie Asset Management Barratt & Cooke Limited EFG Beaufort Equity Limited Fieldings Investment Management Ltd Beckett Asset Management Ltd First Equity Berkeley Futures Limited Fiske Plc Best Invest Brokers (Plc) Fleming Family & Partners Wealth Planning Ltd Blankstone Sington Ltd Forex Capital Markets Ltd Border Asset Management GAM London Bordie & Cie (UK) PLC Gerrard Brewin Dolphin GHC Capital Markets Broadstone Pensions -

Private Client Wealth Management

FINANCIALTIMES|SaturdayJune20 /SundayJune212015 Private Client Wealth Management An FTMoney Guide The robo advisers are coming How to find your wealth manager No way back for bonds? But what effect will they have on the £1.1tn UK An adviser should offer more than just Yields are so low that many industry watchers wealth management market? investments, experts say believe the only way is up PAGE 4 PAGE 7 PAGE 11 2 | FTMoney FINANCIAL TIMES Saturday 20 June 2015 PRIVATE CLIENT WEALTH MANAGEMENT The elusive search for alpha continues OVERVIEW resulted from years of quanti- “This is a situation where horizon to indicate that the Wealth managers tative easing, in which the activemanagersandmanagers equity bull market is over, world’scentralbankshavecol- who take a specific approach although we may have a sum- move higher up lectively injected billions into toinvestmentshouldshine.” merdipaswehaveinthepast,” the risk curve markets across the globe. The Until that shift occurs, port- says Canaccord’s chief invest- FTSE All World, for example, folio construction presents mentofficer,NigelCuming. JUDITH EVANS has been on a rising trajectory particular challenges, espe- PSigma, by contrast, rejects The past three years have not since late 2011, gaining almost ciallyatthecautiousend.“The the increased equity alloca- been straightforward for 60 per cent. The volatility of only real cautious portfolio tions adopted by some rivals, investing. Less than 20 per equities has fallen, while that these days is cash — or a port- instead seeking yield through cent of wealth managers’ of bonds has risen, even as foliothatisveryhighlydiversi- quality fixed income and spe- portfolios have added positive bond yields became tightly fied,”arguesMrBecket. -

Definition of Institutions to Which the Senior Managers Regime and Standards of Conduct Rules Apply 1. This Note Sets out In

UNCLASSIFIED Definition of institutions to which the senior managers regime and standards of conduct rules apply 1. This note sets out in more detail the definition of „bank‟ used for the purposes of the new regime for bank senior managers and banking standards set out in the Financial Services (Banking Reform) Bill as amended in the Lords Committee stage, and explains the effect of the Government‟s Report stage amendments. What is within the definition? 2. Section 71A FSMA, as originally drafted for clause 24 of the Financial Services (Banking Reform) Bill) defines a bank as a UK institution which has a FSMA Part 4A permission to carry on the regulated activity of accepting deposits and which is not an insurer. “UK institution” limits the definition to businesses incorporated or formed under the law of any part of the United Kingdom. The reference to the “regulated activity of accepting deposits” essentially limits the definition to entities which carry on deposit-taking business – that is to say firms which set out to take deposits as their business, not firms that take deposits as an incidental part of some other business.1 It does not limit the definition to purely retail deposit-taking business. 3. The overall effect of these provisions is that the definition of bank in the original section 71A includes all UK banks, building societies and credit unions (including subsidiary companies of foreign banks) but not foreign banks which operate through branches in the UK or any institution which is called a “bank” but does not have a deposit-taking permission. -

Corporate Partners E Executive Member a Associate Member P Practitioner Member O Online Member

Members 2 17 Corporate partners E Executive Member A Associate Member P Practitioner Member O Online Member Piers Currie Group Head of Brand Aberdeen Asset Management E Rachael Laurie Marketing Strategy & Planning Director Aviva A Kim Goodall Head of Long Term Savings Strategy and Aberdeen Asset Management E Lauren Glossop Head of UK Marketing Aviva Investors E Proposition Hazel Pitchers Global Head of Marketing AXA Investment Managers E Daniella Johnston Deputy Head of Marketing - UK Aberdeen Asset Management A Fusan Fidan Interim Head of Web and Social Media AXA Investment Managers A Holly Sheridan-Hill Institutional Marketing Manager Aberdeen Asset Management A Tracy Knatt Head of Web & Social Media AXA Investment Managers E James Whiteman Head of Investment Communications Aberdeen Asset Management A Sanchari Roy Wholesale Marketing Manager AXA Investment Managers A Emily Morris Director Acanthus Consulting O Stephen Watchorn Head of UK Marketing AXA Investment Managers E Niamh Dalton Business Analyst Accudelta O Mary Zerner Institutional Marketing AXA Investment Managers A Liam Houston Business Analyst Accudelta O Martin Bellingham Head of Customer Insight AXA PPP Healthcare A James Haycock Managing Director Adaptive Lab O Paul Humphreys Senior Proposition Executive AXA PPP Healthcare A Bharat Sagar Executive Chairman AE3 Media E Simon Miller Head of Marketing AXA PPP Healthcare A Stephen Leonard Marketing Director Ageas UK Ltd E Mark Howes Managing Director AXA PPP Healthcare E Ken Marke Head of Strategic Futures Ageas UK Ltd E Ian -

Rpt MFI-EU Hard Copy Annual Publication

MFI ID NAME ADDRESS POSTAL CITY HEAD OFFICE RES* UNITED KINGDOM Central Banks GB0425 Bank of England Threadneedle Street EC2R 8AH London No Total number of Central Banks : 1 Credit Institutions GB0005 3i Group plc 91 Waterloo Road SE1 8XP London No GB0015 Abbey National plc Abbey National House, 2 Triton NW1 3AN London No Square, Regents Place GB0020 Abbey National Treasury Services plc Abbey National House, 2 Triton NW1 3AN London No Square, Regents Place GB0025 ABC International Bank 1-5 Moorgate EC2R 6AB London No GB0030 ABN Amro Bank NV 10th Floor, 250 Bishopsgate EC2M 4AA London NL ABN AMRO Bank N.V. No GB0032 ABN AMRO Mellon Global Securities Services Princess House, 1 Suffolk Lane EC4R 0AN London No BV GB0035 ABSA Bank Ltd 75 King William Street EC4N 7AB London No GB0040 Adam & Company plc 22 Charlotte Square EH2 4DF Edinburgh No GB2620 Ahli United Bank (UK) Ltd 7 Baker Street W1M 1AB London No GB0050 Airdrie Savings Bank 56 Stirling Street ML6 OAW Airdrie No GB1260 Alliance & Leicester Commercial Bank plc Building One, Narborough LE9 5XX Leicester No GB0060 Alliance and Leicester plc Building One, Floor 2, Carlton Park, LE10 0AL Leicester No Narborough GB0065 Alliance Trust Savings Ltd Meadow House, 64 Reform Street DD1 1TJ Dundee No GB0075 Allied Bank Philippines (UK) plc 114 Rochester Row SW1P 1JQ London No GB0087 Allied Irish Bank (GB) / First Trust Bank - AIB 51 Belmont Road, Uxbridge UB8 1SA Middlesex No Group (UK) plc GB0080 Allied Irish Banks plc 12 Old Jewry EC2R 8DP London IE Allied Irish Banks plc No GB0095 Alpha Bank AE 66 Cannon Street EC4N 6AE London GR Alpha Bank, S.A. -

Annual Report 1981

The Bank's accounts The Banking Department accounts fo r the year profit transferred 10 reserves amounts to £17.4 ended 28 February 198 1 show an operating profit million, compared with £ 11.2 million last year. of £62.6 million, compared with £25.6 million in 1979/80. This is after charging a total of £13.3 million The current cost accounts, shown on page 29. show in respect of a further payment to the Pension a profit before tax of £34.3 million, some £13.3 Fund to maintain a flll ly-funded position, offset by million less than in the historical cost accounts. a net reduction in provisions for losses in respect of British government and other securities and against advances under the Bank's involvement in The Issue Department accounts are shown on support operations. After a payment in lieu of page 31. The profits of the note issue, payable to the dividend of £15.0 million (compared with £6.5 Treasury, amounted to £[,739.9 million compared million) and a tax charge of £30.2 million, the with £1,328.5 million in [979/80. 17 Report of the Auditors To the GOI'ernor ami Company of fhe Bank of England We have audited the accounts of the Banking 2 The statements of account of the Issue Department Department on pages 19 to 28, and the statements present fairly the outcome of the transactions of of account of the Issue Department set out on the Department for the year ended 28 February page 31, in accordance with approved Auditing 1981 and its balances on that date.