Focus Group Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Review of Part of the Boundary Between the County Boroughs of Blaenau Gwent and Caerphilly Report and Proposals 1

REVIEW OF PART OF THE BOUNDARY BETWEEN THE COUNTY BOROUGHS OF BLAENAU GWENT AND CAERPHILLY REPORT AND PROPOSALS 1. INTRODUCTION 2. SCOPE AND OBJECT OF THE REVIEW 3. DRAFT PROPOSALS 4. SUMMARY OF REPRESENTATIONS RECEIVED IN RESPONSE TO THE DRAFT PROPOSALS 5. ASSESSMENT 6. PROPOSALS 7. CONSEQUENTIAL ARRANGEMENTS 8. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 9. RESPONSES TO THIS REPORT The Rt. Hon Alun Michael JP MP AM First Secretary The National Assembly for Wales 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1 We, the Local Government Boundary Commission for Wales (the Commission), have completed the review of part of the boundary between the County Borough of Blaenau Gwent and the County Borough of Caerphilly in the area of Tafarnaubach and present our proposals for a new boundary. 2. SCOPE AND OBJECT OF THE REVIEW 2.1 Section 54(1) of the Local Government Act 1972 (the Act) provides that the Commission may in consequence of a review conducted by them make proposals to the National Assembly for Wales for effecting changes appearing to the Commission desirable in the interests of effective and convenient local government. Procedure 2.2 Section 60 of the Act lays down procedural guidelines which are to be followed in carrying out a review. In line with that guidance, we wrote on 29 January 1999 to Blaenau Gwent and Caerphilly County Borough Councils, Rhymney and Tredegar Community Councils, the Members of Parliament for the local constituencies, the local authority associations, the police authority for the area and political parties to inform them of our intention to conduct the review and to request their preliminary views. -

1 COUNTY BOROUGH of BLAENAU GWENT Application Address

COUNTY BOROUGH OF BLAENAU GWENT REPORT TO: CHAIR AND MEMBERS OF THE PLANNING COMMITTEE REPORT SUBJECT: LIST OF DELEGATED ITEMS DETERMINED BETWEEN 17TH MARCH 2015 AND 15TH MAY 2015 REPORT AUTHOR: TEAM MANAGER, DEVELOPMENT MANAGEMENT LEAD OFFICER/ SERVICE MANAGER DEVELOPMENT DEPARTMENT Application Address Proposal Valid Date No. Decision Date C/2015/0003 37 & 38 Queen Street, Conversion and extension of property to provide 8 flats, parking and 04/02/2015 Nantyglo alterations to front and rear of property 26/03/2015 Approved C/2014/0320 Swffryd Ganol Farm, Swffryd Proposed repair & renovation works including 2 new external doors & 28/10/2014 external steps & handrail 18/03/2015 Approved C/2015/0076 Land North of Rassau Discharge of condition: 19 - Scheme to upgrade Alan Davies Way of 25/02/2015 Industrial Estate, Rassau planning permission C/2013/0062 Circuit of Wales 15/04/2015 Ebbw Vale Condition Discharged C/2015/0035 6 Walters Avenue, Swfrydd Change of use from existing retail shop to a fish and chip shop (ground 28/01/2015 floor only). 02/04/2015 Refused 1 C/2015/0080 Plots 131 - 136 Larch Lane, Proposed replan at Plots 131-136 including reduction in dwellings (from 24/02/2015 Tredegar six no. to four no.) creating new plot numbering 131-134 on Land to the 20/04/2015 rear of Peacehaven (previously approved under planning permission Approved C/2007/0400) C/2015/0054 12 Laburnum Avenue, Retention of change of use of land to garden land and retention of shed 17/02/2015 Ashvale, Tredegar 10/04/2015 Approved C/2015/0081 Pembroke House Beaufort Retrospective application for change of use of land to domestic curtilage 27/02/2015 Hill, Beaufort, Ebbw Vale and retention of timber framed garage on a plinth, decking area and shed 23/04/2015 Approved C/2015/0036 Plot 2A Maes Morgan Two storey detached house with hardstanding for 3 cars 03/02/2015 Nantybwch, Tredegar 29/04/2015 Approved C/2015/0044 122 Abertillery Road, Blaina Double garage, boundary fence, raised patio area and timber steps to 06/02/2015 upper patio area. -

Planning, Design & Access Statement

PLANNING, DESIGN & ACCESS STATEMENT PCI Pharma Services Unit 23-24 Tafarnaubach Industrial Estate March 2020 T: 029 2073 2652 T: 01792 480535 Cardiff Swansea E: [email protected] W: www.asbriplanning.co.uk PROJECT SUMMARY PCI PHARMA SERVICES, TAFARNAUBACH INDUSTRIAL ESTATE Description of development: Construction of new packaging line building, retaining wall and covered pedestrian walkway linking new packaging line building with new car park (approved under Application Ref C/2019/0195) Location: Unit 23-24 Tafarnaubach Industrial Estate, Tredegar Date: March 2020 Asbri Project ref: 20.159 Client: PCI Pharma Services STATEMENT A C CE S S & PLANNING, DESIGN Asbri Planning Ltd Prepared by Approved by Unit 9 Oak Tree Court Mulberry Drive Geraint Jones Pete Sulley Cardiff Gate Business Park Name Cardiff Planner Director CF23 8RS T: 029 2073 2652 Date March 2020 March 2020 E: [email protected] W: asbriplanning.co.uk Revision M AR C H 2 0 2 0 2 CONTENTS PCI PHARMA SERVICES, TAFARNAUBACH INDUSTRIAL ESTATE Section 1 Introduction 5 Section 2 Site Context and Analysis 6 Section 3 Interpretation 8 Section 4 Design Development 10 Section 5 Planning Policy 12 STATEMENT Section 6 The Proposal 15 Section 7 A C CE S S Appraisal 19 & Section 8 Conclusion 21 PLANNING, DESIGN M AR C H 2 0 2 0 3 PCI PHARMA SERVICES, TAFARNAUBACH INDUSTRIAL ESTATE SITE IN REGIONAL CONTEXT STATEMENT A C CE S S & PLANNING, DESIGN M AR C H 2 0 2 0 4 PCI PHARMA SERVICES, TAFARNAUBACH INDUSTRIAL ESTATE INTRODUCTION 1.1 This Planning, Design and Access Statement (PDAS) -

Adroddiad Report

Adroddiad Report Ymchwiliad a agorwyd ar 10/03/15 Inquiry opened on 10/03/15 Ymweliad safleoedd a wnaed ar amrywiol Site visits made on various dates ddyddiadau gan Emyr Jones BSc(Hons) CEng by Emyr Jones BSc(Hons) CEng MICE MICE MCMI MCMI Arolygydd a benodir gan Weinidogion Cymru an Inspector appointed by the Welsh Ministers Dyddiad: 01 Mehefin 2015 Date: 01 June 2015 COMMONS ACT 2006 APPLICATION TO DEREGISTER PART OF TREFIL-LAS AND TWYN BRYN-MARCH COMMON (BCL015) AT RASSAU, EBBW VALE AND PROVIDE REPLACEMENT LAND Cyf ffeil/File ref: 516000 www.planningportal.gov.uk/planninginspectorate Report APP/X6910/X/14/516000 Contents Page List of abbreviations 2 Case details 3 Procedural Matters 3 The Sites and their Surroundings 5 The Proposals 8 Alternatives and site selection 9 The Case for the Applicants 9 The Case for Natural Resources Wales 34 The Cases for those supporting the application: Mr Nick Smith MP 42 Mr Dai Davies 43 Rev Geoff Waggett 43 Mr Robert Davies 44 Ms Sophie Rose 45 Mr Aled Davies 45 The Cases for those opposing the application: Brecon Beacons Park Society 46 Gwent Wildlife Trust 48 Open Spaces Society 50 Mr William Gibbs 52 Ms Gwyneth Love 54 Written Representations 54 CONCLUSIONS 58 Recommendation 69 Appearances 70 Documents 72 ISBN 978-1-4734-5291-6 www.planningportal.gov.uk/planninginspectorate 1 Report 516000 Abbreviations Biodiversity Action Plan BAP Brecon Beacons Park Society BBPS Brecon Beacons National Park BBNP Blaenau Gwent County Borough Council BGCBC Circuit of Wales CoW Countryside and Rights of Way Act 2000 -

PCI Packaging Facility, Tafarnaubach Industrial Estate, Tredegar

PCI Packaging Facility, Tafarnaubach Industrial Estate, Tredegar Transport Statement March 2020 Applicant: PCI Pharmaceuticals Project no: T20.116 Document ref no: T20.116.TS.D1 Document issue date: March 2020 Project name: PCI Packaging Facility, Tafarnaubach Industrial Estate, Tredegar Offices at: Unit 9, Oak Tree Court Suite D, 1st Floor, Mulberry Drive, 220 High Street, Cardiff Gate Business Park, Swansea, Cardiff, CF23 8RS SA1 1NW Tel: 029 2073 2652 Tel: 01792 480535 DC/POC CONTENTS 1.0 Introduction ................................................................................................... 1 2.0 Existing Situation ........................................................................................... 3 3.0 Sustainable Accessibility ................................................................................. 8 4.0 Development Proposals ............................................................................... 13 5.0 Transport characteristics .............................................................................. 18 6.0 Conclusion ................................................................................................... 20 Appendices Appendix A: Previous Planning Consents Appendix B: Approved Car Park and CMF2 Facility Appendix C: PIC STATS19 Information Appendix D: SEWLTP Extract for Active Travel Improvement scheme Appendix E: Site Layout Plan Appendix F: Construction Traffic Management Plan 1.0 INTRODUCTION 1.1 Background 1.1.1 Asbri Transport Limited is acting on behalf of PCI Pharmaceuticals -

Refuse Routes 2016

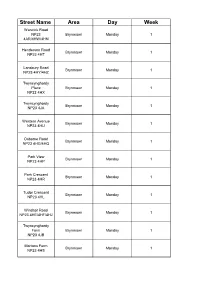

Street Name Area Day Week Warwick Road NP23 Brynmawr Monday 1 4AR/4HW/4HN Henderson Road Brynmawr Monday 1 NP23 4HT Lansbury Road Brynmawr Monday 1 NP23 4HY/4HZ Twyncynghordy Place Brynmawr Monday 1 NP23 4HX Twyncynghordy Brynmawr Monday 1 NP23 4JA Western Avenue Brynmawr Monday 1 NP23 4HU Osborne Road Brynmawr Monday 1 NP23 4HG/4HQ Park View Brynmawr Monday 1 NP23 4HP Park Crescent Brynmawr Monday 1 NP23 4HR Tudor Crescent Brynmawr Monday 1 NP23 4HL Windsor Road Brynmawr Monday 1 NP23 4HE/4HF/4HJ Twyncynghordy Farm Brynmawr Monday 1 NP23 4JB Mortons Farm Brynmawr Monday 1 NP23 4HS Brook Street Brynmawr Monday 1 NP23 4HH Well Street Brynmawr Monday 1 NP23 4TP/4HD George Street Brynmawr Monday 1 NP23 4TW Bath Lane Brynmawr Monday 1 NP23 4TR Heol Helig Brynmawr Monday 1 NP23 4TZ/4TY Heol Onen Brynmawr Monday 1 NP23 4TS Heol Derw Brynmawr Monday 1 NP23 4TT King Street NP23 4DG/4DQ/4RF/4SY Brynmawr Monday 1 4RG/4SZ/4ST/4SU/4 DH Cosy Place (flats) Brynmawr Monday 1 NP23 4RQ Dumfries Place Brynmawr Monday 1 NP23 4RA Church Lane Brynmawr Monday 1 NP23 4RH Cemetery Road Brynmawr Monday 1 NP23 4TN The Hendre Brynmawr Monday 1 NP23 4TH Heol Isaf Brynmawr Monday 1 NP23 4TL Heol Ganol Brynmawr Monday 1 NP23 4TJ Gurnos Estate NP23 Brynmawr Monday 1 4TE/4TF/4TG/4TQ Harcourt Road Brynmawr Monday 1 NP23 4TU Hill Crest Brynmawr Monday 1 NP23 4TB Hill Street Brynmawr Monday 1 NP23 4SX Hill Crescent Brynmawr Monday 1 NP23 4TA Birch Grove Brynmawr Monday 1 NP23 4TD Fitzroy Street Brynmawr Monday 1 NP23 4RX Sunny Bank Brynmawr Monday 1 NP23 4RJ Brynawel Brynmawr -

Roadside Verge Biodiversity Survey– We Need Your Help!

Roadside Verge Biodiversity Survey– We Need Your Help! The council is dedicated in trying to preserve and enhance the biodiversity of roadside verges within Blaenau Gwent. As a result, the council is looking to find the best roadside verges for wild- life within the county borough. We are asking the local residents of the borough to help us by sending in your records of verges which display the best opportunities for wildlife. Blaenau Gwent has an abundance of biodiversity which has formed as part of the wide variety of the inter– relationships between habitats. Roadside verges are incredibly important as the habitat they provide act as wildlife corridors for insects, mammals, and birds, forming a vital link between other wildlife areas. Some verges provide such a valuable variety of species rich habitat, such as heath, grassland and woodland, that they are able to support some of our rare and scarce species present in this area, many of which are included in our Local Biodiversity Action Plan. Tell us about the roadside verges in your area that are rich in biodiversity over the spring and summer by filling in the tear off slip below and sending to the return address, or by emailing [email protected] for further information. By providing us with this information you will greatly help us to sympathetically manage the verges for the wildlife. For example, a late summer cut of a grass verge allows the plants and vegetation to flower and set seed, which helps to guarantee the wildflowers and other flowering plants to thrive, whilst providing a vital source of food and cover for species such as bees and butterflies. -

BID) for the Rassau and Tafarnaubach Industrial Estates, Ebbw Vale

Report On The Feasibility Of A Business Improvement District (BID) For the Rassau and Tafarnaubach Industrial Estates, Ebbw Vale Prepared By Revive & Thrive Ltd On Behalf Of Blaenau Gwent County Borough Council February 2019 1.0 Executive Summary In autumn 2018, Revive & Thrive was commissioned by Blaenau Gwent County Borough Council to work with them on the production of a feasibility study for the implementation of a Business Improvement District (BID) for the Rassau and Tafarnaubach Industrial Estates. Dependent upon the outcome of the feasibility stage, the commission was to then see the BID through to ballot and subsequent BID Company set-up, if the ballot is successful. The funding for the project has come from a Welsh Government allocation of £270,000 to support the establishment of up to ten new BIDs across Wales and, if it is successful at ballot, the Rassau and Tafarnaubach BID would become the first industrial BID in Wales. In developing this report, the Revive & Thrive project team has conducted face-to-face, telephone and online surveys with businesses across the two estates. This has been complemented by a series of email requests and an introductory presentation on BIDs, to which all businesses were invited. In order to establish the feasibility or otherwise of a BID on the Rassau and Tafarnaubach Industrial Estates, two fundamental principles have needed consideration: 1) That a BID for the estates has the broad support of the business community. As BIDs are inherently business-led and -driven, any potential BID would need the buy-in of the majority of businesses. -

Innova One Tredegar Business Park, Tredegar, NP22 3EL 5,676 – 30,020 Sq Ft Flexible High Specification Modern Office/Warehouse A40 Sennybridge 470 A

To Let For Sale Innova One Tredegar Business Park, Tredegar, NP22 3EL 5,676 – 30,020 sq ft Flexible High Specification Modern Office/Warehouse A40 Sennybridge 470 A BLACK A A Brecon 479 M5 4215 MOUNTAINS A40 Ross-on-Wye A BRECON BEACONS 466 465 A 40 NATIONAL PARK A A 470 465 A Monmouth 4059 A A Tredegar Abergavenny 4221 A40 12 Blaina A465 Merthyr Ebbw Raglan A Glyn- Tydfil 467 13 The property is situated in Tredegar Business Park, ValeA A 4046 466 Neath 48 Hirwaun 449 A 4042 A A Aberdare A 465 4061 A A 470 A Pontypool part of the Ebbw Vale Enterprise Zone. Designated A A 4059 469 467 5 Cwmbran Usk M Neath N R Tonypandy E as a Tier 1 area, Tredegar Business Park has the SWANSEA Chepstow V 14 42 A4058 E A48 22 S M Pontypridd 4 M M Modern Office/ 48 41 26 24 4 21 41 A468 23 potential to benefit from The Wales Enterprise Tonyrefail 27 48 40 A A A Port 4119 470 M4 39 Caerphilly 28 20 Talbot 38 29 NEWPORT 15 30 16 Llantrisant 49 Zone Business Rates Scheme and financial support 36 32 M 17 37 35 19 34 33 A A48 BRISTOL 4232 18 M4 CHANNEL Avonmouth Warehouse from Welsh, UK and EU funding sources. Tredegar Bridgend 19 32 A48 M CARDIFF 5 M BRISTOL A Business Park is within walking distance of Cardiff 20 37 4050 A International A 4 Barry A38 Airport 370 A Tredgear Town Centre. The nearest Train station is 21 Weston-Super-Mare Rhymney which lies 3 miles west of Tredegar with 5 M a direct service to Cardiff Central. -

BLAENAU GWENT COUNTY BOROUGH COUNCIL Report To

Report Date: Report Author: BLAENAU GWENT COUNTY BOROUGH COUNCIL Report to The Chair and Members of Planning, Regulatory and General Licensing Report Subject Planning Applications Report Report Author Team Manager Development Management Report Date 27th January 2020 Directorate Regeneration & Community Services Date of meeting 6th February 2020 Report Information Summary 1. Purpose of Report To present planning applications for consideration and determination by Members of the Planning Committee. 2. Scope of the Report Application No. Address C/2019/0310 1 Hawthorn Glade, Tanglewood, Blaina, NP13 3JT C/2019/0330 Unit 2, Tafarnaubach Industrial Estate, Tafarnaubach C/2019/0280 Wauntysswg Farm Abertysswg Rhymney Tredegar NP22 5BQ C/2019/0269 10 Castle Street, Tredegar, NP22 3DE C/2019/0346 Site of former sheltered housing at Glanffrwd Court and adjacent land at Cae Melyn and Rhiw Wen, Ebbw Vale C/2019/0273 The Bridge, Hotel and Flat, Station Approach, Pontygof, Ebbw Vale C/2019/0308 30 Marine Street, Cwm, Ebbw Vale 3. Recommendation/s for Consideration Please refer to individual reports Report Date: Report Author: Planning Report Application C/2019/0310 App Type: Retention No: Applicant: Agent: Mr. Jamie Davies Mr T Morgan 1 Hawthorn Glade Clifton House Blaina Westside NP13 3JT Blaina, NP13 3DD Site Address: 1 Hawthorn Glade, Tanglewood, Blaina, NP13 3JT Development: Retention and extension of raised decking area Case Officer: Joanne White Application Site 1. Background, Development and Site Context 1.1 This application seeks permission to retain and extend a raised decked area within the rear garden of a detached residential property. The dwelling occupies a corner plot within the estate commonly known as ‘Tanglewood’, Blaina. -

Transition from Ebbw Vale Enterprise Zone to Tech Valleys

Transition from Ebbw Vale Enterprise Zone to Tech Valleys Mark Langshaw MBE Managing Director Continental Teves UK Ltd Chair, Ebbw Vale Enterprise Zone/TechValleys Strategic Advisory Boards Background • EZ established by Welsh Government in 2012 • Objective – to sustain and create jobs & improve GVA in the area • Ebbw Vale one of eight zones in Wales • Enterprise Zones are designated geographical areas that support new and expanding businesses by providing business infrastructure and support • The Ebbw Vale Enterprise Zone focuses primarily on the advanced materials and manufacturing sector • Advisory Board appointed, private sector led • Partnership Welsh Government / local government / private sector Vision for EVEZ will be of a vibrant; world class high technology hotspot for Welsh based manufacturing companies of all sizes spanning many key sub sectors, providing employment that is challenging, rewarding and valued Objective – jobs and growth creation Support the improvement of infrastructure links and development of circa 450,000 sq. ft. of new industrial /commercial floor space, which could generate up to £20 million of private sector investment and the potential to accommodate 1,000 permanent jobs PLUS employment during construction phases Roles and Responsibilities • Recommendation and implementation of strategic interventions and priorities to secure jobs and investment • Monitor/challenge progress on key areas, including • strategic advice towards investment opportunities • encouraging supply chain development • Identifying needs -

Bevan Foundation

About the Bevan Foundation The Bevan Foundation is Wales’ most influential think tank. We develop lasting solutions to poverty and inequality, and make a difference to people’s lives. Our vision is for Wales to be a nation where everyone has a decent standard of living, a healthy and fulfilled life, and a voice in the decisions that affect them. As an independent, registered charity, the Bevan Foundation relies on the generosity of individuals and organisations for its work. How you can help Hundreds of people and organisations across Wales enable the Bevan Foundation to speak out against poverty, inequality and injustice. We would not exist without their support. Please join our community of supporters and get some great benefits too. Find out more at https://www.bevanfoundation.org/support-us/individuals/ or email [email protected] Cover image: Industrial units along the A465 Alamy stock image Bevan Foundation, 145a High Street, Merthyr Tydfil CF47 8DP www.bevanfoundation.org [email protected] 01685 350938 Registered charity: 1104191 Contents Summary ............................................................................................................................................... 2 1. Introduction .................................................................................................................................. 3 2. Challenges and opportunities ................................................................................................... 4 2.1. The opportunities ...............................................................................................................