[Pages 516 – 552] Chapter 1 the Nature of the Atma a Word to The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ADVAITA-SAADHANAA (Kanchi Maha-Swamigal's Discourses)

ADVAITA-SAADHANAA (Kanchi Maha-Swamigal’s Discourses) Acknowledgement of Source Material: Ra. Ganapthy’s ‘Deivathin Kural’ (Vol.6) in Tamil published by Vanathi Publishers, 4th edn. 1998 URL of Tamil Original: http://www.kamakoti.org/tamil/dk6-74.htm to http://www.kamakoti.org/tamil/dk6-141.htm English rendering : V. Krishnamurthy 2006 CONTENTS 1. Essence of the philosophical schools......................................................................... 1 2. Advaita is different from all these. ............................................................................. 2 3. Appears to be easy – but really, difficult .................................................................... 3 4. Moksha is by Grace of God ....................................................................................... 5 5. Takes time but effort has to be started........................................................................ 7 8. ShraddhA (Faith) Necessary..................................................................................... 12 9. Eligibility for Aatma-SAdhanA................................................................................ 14 10. Apex of Saadhanaa is only for the sannyAsi !........................................................ 17 11. Why then tell others,what is suitable only for Sannyaasis?.................................... 21 12. Two different paths for two different aspirants ...................................................... 21 13. Reason for telling every one .................................................................................. -

Mandukya Upanishad Class 6

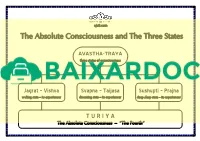

Mandukya Upanishad Class 6 Mantra # 5: That is the state of deep sleep wherein the sleeper does not desire any objects nor does he see any dream. The third quarter (pada) is the “Prajna” whose sphere is deep sleep, in whom all (experiences) become unified or undifferentiated, who is verily a homogeneous mass of Consciousness entire, who is full of bliss, who is indeed an enjoyer of bliss and who is the very gateway for projection of consciousness into other two planes of Consciousness-the dream and the waking. Swamiji said the four padas are being explained from mantra # 3. First pada is the sthula atma where “I”, Chaitanyam, am connected with Sthula nama rupa. When I am connected with one sthula nama rupa I am vishwa sthula atma. When I am connected with samashti, I am called Samashti Sthula atma. In second pada or mantra the sukshma atma has both micro and macro aspects to it. Thus, I have Vyashti and samashti aspects in dream state. Vyashti is Taijasa and samashti is Hiranyagarbha. In the fifth mantra we have come to karana atma. Here I am in shushupti avastha associated with karana nama rupas, all in potential form. Individual nama rupa are called Pragya karana atma. All nama rupa’s in potential form are called anataryami karana atma. In jagrat and svapna avastha micro and macrocosm are visibly different while in sushupti I can’t differentiate between Vyashti and samashti; however, differences do exist. Pragya and anatharyami are physically visible but theoretically we should know that they are different. -

'I AM THAT I AM': Speaking in Time OT: Exodus 3: 13-15. NT: John 8: 52-9

‘I AM THAT I AM’: Speaking in Time OT: Exodus 3: 13-15. NT: John 8: 52-9 ‘Jesus said unto them, Verily, verily, I say unto you, Before Abraham was, I am.’ (John 8: 58). Tonight we begin a sermon series in which we ponder what we do not know about the God we worship. This is a very proper contemplation for finite creatures to make, since any God whose attributes and inwardness were fully known would, by definition, be one too small to be more than our own creation, rather than being -as He is - the One who creates. On the other hand the liturgical season of Epiphany is, on the face of it, an unexpected time to start. It is the season which moves into light, the season in which God shows Himself in the person of His Son; when we come closest to knowing what we do not know; where our blindness becomes sight and our deafness understanding. And the readings we have heard are, among other things, theophanies, God-showings – moments when God speaks directly to His people about Himself, when He discloses something of what He is. But these moments of disclosure are mysterious. What, or whom, is being shown, and what sense can we creatures make of it? How far is God prepared to reach towards us in order to establish anything we could understand as a relationship? a conversation? a meeting? Outside time and outside space where is the sense in speech or the place for response? The two readings, which themselves are part of an historical narrative of the acts of God in communion with His creatures, tell us something of the intentions of the God we do not fully know. -

Indian Psychology: the Connection Between Mind, Body, and the Universe

Pepperdine University Pepperdine Digital Commons Theses and Dissertations 2010 Indian psychology: the connection between mind, body, and the universe Sandeep Atwal Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.pepperdine.edu/etd Recommended Citation Atwal, Sandeep, "Indian psychology: the connection between mind, body, and the universe" (2010). Theses and Dissertations. 64. https://digitalcommons.pepperdine.edu/etd/64 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by Pepperdine Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Pepperdine Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]. Pepperdine University Graduate School of Education and Psychology INDIAN PSYCHOLOGY: THE CONNECTION BETWEEN MIND, BODY, AND THE UNIVERSE A clinical dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Psychology by Sandeep Atwal, M.A. July, 2010 Daryl Rowe, Ph.D. – Dissertation Chairperson This clinical dissertation, written by Sandeep Atwal, M.A. under the guidance of a Faculty Committee and approved by its members, has been submitted to and accepted by the Graduate Faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PSYCHOLOGY ______________________________________ Daryl Rowe, Ph.D., Chairperson ______________________________________ Joy Asamen, Ph.D. ______________________________________ Sonia Singh, -

ADVAITA 18 Diagrams Combined

ajati.com The Absolute Consciousness and The Three States AVASTHA-TRAYA three states of consciousness Jagrat – Vishva Svapna – Taijasa Sushupti – Prajna waking state – its experiencer dreaming state – its experiencer deep sleep state – its experiencer TURIYA The Absolute Consciousness – “The Fourth“ ajati.com Bodies, Sheaths, States and Internal Instrument Sharira-Traya Pancha-Kosha Avastha-Traya Antahkarana Three Bodies Five Sheaths Three States Internal Instrument Sthula Sharira Annamaya Kosha Jagrat - Waking Ahamkara - Ego - Active (1) (1) (1) Buddhi - Intellect - Active Gross Body Food Sheath Vishva - Experiencer Manas - Mind - Active Chitta - Memory - Active Pranamaya Kosha (2) Vital Sheath Ahamkara - Ego - Inactive Sukshma Sharira Manomaya Kosha Svapna - Dream Buddhi - Intellect - Inactive (2) (3) (2) Subtle Body Mental Sheath Taijasa - Experiencer Manas - Mind - Inactive Chitta - Memory - Active Vijnanamaya Kosha (4) Intellect Sheath Ahamkara - Ego - Inactive Karana Sharira Anandamaya Kosha Sushupti - Deep Sleep Buddhi - Intellect - Inactive (3) (5) (3) Manas - Mind - Inactive Causal Body Bliss Sheath Prajna - Experiencer Chitta - Memory - Inactive ajati.com Description of Ignorance Ajnana – Characteristics Anadi Anirvachaniya Trigunatmaka Bhavarupa Jnanavirodhi Indefinable either as Made of three Experienced, Removed by Beginningless real (sat) or unreal (asat) tendencies (guna-s) hence present knowledge (jnana) Sattva Rajas Tamas Ajnana – Powers Avarana - Shakti Vikshepa - Shakti Veiling Power Projecting Power veils jiva 's real -

Vaishvanara Vidya.Pdf

VVAAIISSHHVVAANNAARRAA VVIIDDYYAA by Swami Krishnananda The Divine Life Society Sivananda Ashram, Rishikesh, India (Internet Edition: For free distribution only) Website: www.swami-krishnananda.org CONTENTS Publishers’ Note 3 I. The Panchagni Vidya 4 The Course Of The Soul After Death 5 II. Vaishvanara, The Universal Self 26 The Heaven As The Head Of The Universal Self 28 The Sun As The Eye Of The Universal Self 29 Air As The Breath Of The Universal Self 30 Space As The Body Of The Universal Self 30 Water As The Lower Belly Of The Universal Self 31 The Earth As The Feet Of The Universal Self 31 III. The Self As The Universal Whole 32 Prana 35 Vyana 35 Apana 36 Samana 36 Udana 36 The Need For Knowledge Is Stressed 37 IV. Conclusion 39 Vaishvanara Vidya Vidya by by Swami Swami Krishnananda Krishnananda 21 PUBLISHERS’ NOTE The Vaishvanara Vidya is the famous doctrine of the Cosmic Meditation described in the Fifth Chapter of the Chhandogya Upanishad. It is proceeded by an enunciation of another process of meditation known as the Panchagni Vidya. Though the two sections form independent themes and one can be studied and practised without reference to the other, it is in fact held by exponents of the Upanishads that the Vaishvanara Vidya is the panacea prescribed for the ills of life consequent upon the transmigratory process to which individuals are subject, a theme which is the central point that issues from a consideration of the Panchagni Vidya. This work consists of the lectures delivered by the author on this subject, and herein are reproduced these expositions dilating upon the two doctrines mentioned. -

DHYANA VAHINI Stream of Meditation

DHYANA VAHINI Stream of Meditation SATHYA SAI BABA Contents Dhyana Vahini 5 Publisher’s Note 6 PREFACE 7 Chapter I. The Power of Meditation 10 Binding actions and liberating actions 10 Taming the mind and the intelligence 11 One-pointedness and concentration 11 The value of chanting the divine name and meditation 12 The method of meditation 12 Chapter II. Chanting God’s Name and Meditation 14 Gauge meditation by its inner impact 14 The three paths of meditation 15 The need for bodily and mental training 15 Everyone has the right to spiritual success 16 Chapter III. The Goal of Meditation 18 Control the temper of the mind 18 Concentration and one-pointedness are the keys 18 Yearn for the right thing! 18 Reaching the goal through meditation 19 Gain inward vision 20 Chapter IV. Promote the Welfare of All Beings 21 Eschew the tenfold “sins” 21 Be unaffected by illusion 21 First, good qualities; later, the absence of qualities 21 The placid, calm, unruffled character wins out 22 Meditation is the basis of spiritual experience 23 Chapter V. Cultivate the Blissful Atmic Experience 24 The primary qualifications 24 Lead a dharmic life 24 The eight gates 25 Wish versus will 25 Take it step by step 25 No past or future 26 Clean and feed the mind 26 Chapter VI. Meditation Reveals the Eternal and the Non-Eternal 27 The Lord’s grace is needed to cross the sea 27 Why worry over short-lived attachments? 27 We are actors in the Lord’s play 29 Chapter VII. -

Brahma Sutra

BRAHMA SUTRA CHAPTER 4 3rd Pada 1st Adikaranam to 6th Adhikaranam Sutra 1 to 16 INDEX S. No. Topic Pages Topic No Sutra No introduction 4024 179 Archiradyadhikaranam 179 a) Sutra 1 4026 179 518 180 Vayvadhikaranam 180 a) Sutra 2 4033 180 519 181 Tadidadhikaranam 4020 181 a) Sutra 3 4044 181 520 182 Ativahikadhikaranam 182 a) Sutra 4 4049 182 521 b) Sutra 5 4054 182 522 c) Sutra 6 4056 182 523 i S. No. Topic Pages Topic No Sutra No 183 Karyadhikaranam: 183 a) Sutra 7 4068 183 524 b) Sutra 8 4070 183 525 c) Sutra 9 4073 183 526 d) Sutra 10 4083 183 527 e) Sutra 11 4088 183 528 f) Sutra 12 4094 183 529 g) Sutra 13 4097 183 530 h) Sutra 14 4099 183 531 184 Apratikalambanadhikaranam: 184 a) Sutra 15 4118 184 532 b) Sutra 16 4132 184 533 ii Lecture 368 4th Chapter : • Phala Adhyaya, Phalam of Upasaka Vidya. Mukti Phalam Saguna Vidya Nirguna Vidya - Upasana Phalam - Aikya Jnanam - Jnana Phalam • Both together is called Mukti Phalam Trivida Mukti (Threefold Liberation) Jeevan Mukti Videha Mukti Krama Mukti Mukti / Moksha Phalam Positive Language Negative Language - Ananda Brahma Prapti - Bandha Nivritti th - 4 Pada - Samsara Nivritti rd - 3 Pada - Dukha Nivritti - Freedom from Samsara, Bandha, Dukham st - 1 Pada Freedom from bonds of Karma, Sanchita ( Destroyed), Agami (Does not come) - Karma Nivritti nd - 2 Pada nd rd • 2 and 3 Padas complimentary both deal with Krama Mukti of Saguna Upasakas, Involves travel after death.4024 Krama Mukti Involves Travel 3 Parts / Portions of Krama Mukti 2nd Pada – 1st Part 2nd Part Travel 3rd Part Reaching Departure from Body for Travel Gathi Gathanya Prapti only for Krama Mukti - Not for Videha Mukti or Jeevan Mukti - Need not come out of body - Utkranti - Panchami – Tat Purusha Utkranti – 1st Part - Departure Pranas come to Hridayam Nadis Dvaras Shine Small Dip in Brahma Loka Appropriate Nadi Dvara Jiva goes • 2nd Part Travel - Gathi and Reaching of Krama Mukti left out. -

Indian Philosophy Encyclopædia Britannica Article

Indian philosophy Encyclopædia Britannica Article Indian philosophy the systems of thought and reflection that were developed by the civilizations of the Indian subcontinent. They include both orthodox (astika) systems, namely, the Nyaya, Vaisesika, Samkhya, Yoga, Purva-mimamsa, and Vedanta schools of philosophy, and unorthodox (nastika) systems, such as Buddhism and Jainism. Indian thought has been concerned with various philosophical problems, significant among them the nature of the world (cosmology), the nature of reality (metaphysics), logic, the nature of knowledge (epistemology), ethics, and religion. General considerations Significance of Indian philosophies in the history of philosophy In relation to Western philosophical thought, Indian philosophy offers both surprising points of affinity and illuminating differences. The differences highlight certain fundamentally new questions that the Indian philosophers asked. The similarities reveal that, even when philosophers in India and the West were grappling with the same problems and sometimes even suggesting similar theories, Indian thinkers were advancing novel formulations and argumentations. Problems that the Indian philosophers raised for consideration, but that their Western counterparts never did, include such matters as the origin (utpatti) and apprehension (jñapti) of truth (pramanya). Problems that the Indian philosophers for the most part ignored but that helped shape Western philosophy include the question of whether knowledge arises from experience or from reason and distinctions such as that between analytic and synthetic judgments or between contingent and necessary truths. Indian thought, therefore, provides the historian of Western philosophy with a point of view that may supplement that gained from Western thought. A study of Indian thought, then, reveals certain inadequacies of Western philosophical thought and makes clear that some concepts and distinctions may not be as inevitable as they may otherwise seem. -

The Philosophy of the Upanisads

THE PHILOSOPHY OF THE UPANISADS BY S. RADHAKRISHNAN WITH A FOREWORD BY RABINDRANATH TAGORE AND AN INTRODUCTION BY EDMOND HOLMES " AUTHOR OF THE CREED OF BUDDHA," ETC. LONDON : GEORGE ALLEN & UNWIN LTD. RUSKIN HOUSE, 40 MUSEUM STREET, W.C. i NEW YORK: THE MACMILLAN COMPANY {All rights reserved) Atfl> ITOKCMO DEDICATION TO THE REV. W. SKINNER, M.A., D.D., ETC. INDIAN PHILOSOPHY BY S. RADHAKRISHNAN George V Profe*or of Phflo*ophy b the Uomratjr of Calcatta i Demy 8v. Two 0ob. 21*. each SOME PRESS OPINIONS " We are fortunate in that Professor Radhakrishnan is evidently deeply read in the Philosophy of the West, and shows considerable blend of acquaintance with general Western literature ; a happy Eastern conceptions with Western terminology makes the book intelligible even to the inexpert, and, it need hardly be added, instructive.'* The Times " In this very interesting, Incid, and admirably written book . the author has given us an interpretation of the Philosophy of India written by an Indian scholar of wide culture." Daily News. 44 It is among the most considerable of the essays in interpre- tation that have come from Indian scholars in recent years. English readers are continually on the look-out for a compendium of Indian thought wntten by a modern with a gift for lucid statement . Here is the book for them." New Statesman. 41 The first volume takes us to the decay of Buddism in India after dealing with the Vedas, the Upanisads, and the Hindu con- temporaries of the early Buddists. The work is admirably done*" BBRTRAND RUSSELL in the Nation. -

What Is Causal Body (Karana Sarira)?

VEDANTA CONCEPTS Sarada Cottage Cedar Rapids July 9, 2017 Peace Chanting (ShAnti PAtha) Sanskrit Transliteration Meaning ॐ गु셁땍यो नमः हरी ओम ्। Om Gurubhyo Namah Hari Om | Salutations to the Guru. सह नाववतु । Saha Nau-Avatu | May God Protect us Both, सह नौ भुन啍तु । Saha Nau Bhunaktu | May God Nourish us Both, सह वीयं करवावहै । Saha Viiryam Karavaavahai| May we Work Together तेजस्वव नावधीतमवतु मा Tejasvi Nau-Adhiitam-Astu Maa with Energy and Vigour, वव饍ववषावहै । Vidvissaavahai | May our Study be ॐ शास््तः शास््तः शास््तः । Om Shaantih Shaantih Enlightening and not give हरी ओम ्॥ Shaantih | Hari Om || rise to Hostility Om, Peace, Peace, Peace. Salutations to the Lord. Our Quest Goal: Eternal Happiness End of All Sufferings Transcending Birth & Death Problem: Fleeting Happiness Endless Suffering Cycle of Birth & Death 3 Vedanta - Introduction Definition: Veda = Knowledge, Anta = End End of Vedas Culmination or Essence of Vedas Leads to God (Truth) Realization Truth: Never changes; beyond Time-Space-Causation Is One Is Beneficial Transforms us Leads from Truth Speaking-> Truth Seeking-> Truth Seeing 4 Vedantic Solution To Our Quest Our Quest: Vedantic Solution: Goal: Cause of Problem: Ignorance (avidyA) of our Real Eternal Happiness Nature End of All Sufferings Attachment (ragah, sangah) to fleeting Objects & Relations Transcending Birth & Death Problem: Remedy: Fleeting Happiness Intense Spiritual Practice (sadhana) Endless Suffering Liberation (mukti/moksha) Cycle of Birth & Death IdentificationIdentification && -

Upanishads Divine Discourses of Bhagawan Sri Sathya Sai Baba

Summer Showers 1991 - Upanishads Divine Discourses of Bhagawan Sri Sathya Sai Baba Index Of Discourses 1. The End Of Education Is Character ...................................................................... 2 2. The Vedic Heritage Of India ................................................................................. 15 3. Thath Twam Asi —that Thou Art......................................................................... 31 4. Isaavaasya Upanishad – Renunciation And Pleasure ........................................ 42 5. Kenopanishad ......................................................................................................... 55 6. Prasnopanishad – Answers To The First Student .............................................. 65 7. Prasnopanishad – Answers To The Second And Third Students ..................... 80 8. Prasnopanishad – Answers To The Fourth And Fifth Students ....................... 90 9. Prasnopanishad – Answers To The Sixth Student ............................................ 101 10. Mundaka Upanishad And Brahma Vidya ......................................................... 109 11. Taittireya Upanishad ........................................................................................... 117 12. The Three Forms Of God – Viraat, Hiranyagarbha And Avyaakruta .......... 128 13. Spiritual Discipline (sadhana) ............................................................................. 144 14. Dharma And Indian Spirituality ........................................................................ 154