Fair Trade and Development

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Paying the Price for Cocoa

QUARTERLY RETURN 113 AUTUMN 2019 PAYING THE PRICE FOR COCOA A SWAHILI SHARING SPIRIT Swahili Imports works with artisans in 15 African countries. A BIG THANK YOU To our volunteers who helped us out at festivals this Summer. SATIPO & ASUNAFO Read the story behind your chocolate bar. ONLINE PORTAL THE IMPORTANCE OF While we are aware that many of you still prefer INCREASING paper communication, we are conscious of its environmental impact. For this reason, we INVESTMENT encourage people to manage their Share Account online if they can. As a result, over a third of As Shared Interest Society reaches 10,000 members are registered to use our online portal, Share Accounts, our organisation’s growth ‘Our Shared Interest.’ can be a source of pride in work well done. It ensures that our reach is greater as we By signing up online, you can view your latest and increase our assets and so our potential to previous statements, change selected personal influence events around the world. details, as well as investing further and making withdrawals. For security purposes, all online withdrawals will be made into your nominated Like most of us, I am not an economist bank account. If your Share Account has more by training, so my grasp of the practical than one signatory, any transactional requests workings of forces of supply and demand will need to be approved by all parties before is hazy. However, what struck me clearly being actioned. in my first meeting as a new Council YOU CAN NOW INVEST member this Summer, was the frustration Instead of receiving your quarterly statement and that exists when the organisation does not WELCOME newsletter in the post, you will receive an email have enough money to satisfy need. -

Nickelodeon's Kids' Choice Awards Slimes Its Way to the Uk

NICKELODEON'S KIDS' CHOICE AWARDS SLIMES ITS WAY TO THE UK SUPERSTAR ROCKERS MCFLY TO HOST THE 1ST EVER NICKELODEON KIDS’ CHOICE AWARDS UK! 1ST NOMINEES EVER FOR KIDS’ CHOICE AWARDS INCLUDE Fall Out Boy, Sugababes, Girls Aloud, McFly, Mika, Cheryl Cole, Justin Timberlake, Drake Bell, Hilary Duff, Avril Lavigne, Gwen Stefani, Simon Cowell, Cameron Diaz, Jack Black, Harry Hill, Mr Bean, Catherine Tate, Lewis Hamilton, David Beckham, Dame Kelly Holmes, Dakota Fanning, Emma Watson, Keira Knightley, Daniel Radcliffe, Johnny Depp, Orlando Bloom, Rowan Atkinson &, Ant & Dec London/New York, 30 July, 2007: The 1st ever Nickelodeon Kids’ Choice Awards UK is quickly shaping up to be the no-holds-barred mess-fest it is known for around the world! Multi platinum- selling, superstar rockers McFly are confirmed to host the all-star, all-sliming awards ceremony on Saturday, 20th October 2007, live at ExCel London. True to the Kids Choice Awards tradition, whether in the US, Italy, China or Brasil, kids will rule the day in the UK and stars will rejoice, as they honour their favorites from the worlds of film, music, sports and television in a star-studded live event. McFly said: "The awards are huge in the US, with the most recent being presented by Justin Timberlake. We're really honoured to be hosting the 1st ever Nickelodeon Kids' Choice Awards in the UK - we're going to break the slime barrier!" No Nickelodeon Kids’ Choice Awards would be complete without a super-sized celebrity soaking and the Kids’ Choice Awards UK promises to deliver its highest honour, a green and gooey shower of slime, atop a very special guest star – but who will it be? Previous slimees include: Cameron Diaz, Justin Timberlake, Tom Cruise and Vince Vaughn. -

Sustainable Trade – No Aid

October, 2020 Sustainable Trade – No Aid Sustainable Global Value Chain Management in the Cacao Industry · taking a Collaborative Approach Anna Verbrugge Master’s Thesis for the Environment and Society Studies programme Nijmegen School of Management Radboud University If you want to go fast, go alone. If you want to go far, go together – African saying (Mout, 2019) i Colophon Document title: Sustainable Global Value Chain Management in the Cocoa Industry · taking a Collaborative Approach Project: Master thesis (MAN-MTHCS) Date: October 25, 2020 Word count: 30124 Version: Concept version Author: Anna Verbrugge Student number: 1039167 Education: MSc Environment and Society Studies, Radboud University Supervisor: Rikke Arnouts Second reader: S. Veenman ii Abstract This research aims to define what is missing in the current business approaches of chocolate companies that sustainability issues in the cocoa sector are commonplace. Despite the many initiatives of the companies and many billions of dollars spent by stakeholders to strengthen sustainability in the industry, real solutions seem a long way off. Chocolate companies seem busier with improving their own chains than with developing a holistic action plan to tackle the structural issues in the sector. To this end, this research examines what it is that makes a global value chain sustainable and how chocolate companies could drive sustainable change beyond their chains. By taking a collaborative approach, this research explores how a collaborative approach within and beyond the chains can help chocolate companies to scale up sustainability solutions and to make a greater sustainable impact in the sector as a whole. To explore the potential added value of a collaborative approach, a case study is conducted on three chocolate companies and sustainable pioneers in the cocoa industry: Tony’s Chocolonely, Divine Chocolate and Zotter. -

“When We Attend to the Needs of Those in Want, We Give Them What Is Theirs

! ! ! ! ! ! "When we attend to the needs of those in want, we give them what is theirs, not ours. More than performing works of mercy, we are paying a debt of justice.” Pope St. Gregory the Great! At one level, Fair Trade is a certification, making sure farmer and artisan cooperatives are meeting criteria. At another level it is our chance to live the Gospel message; to be truly “one body” with those who produce the food and goods we need and want. Fair Trade is about relationships. Being a follower of Jesus is also about relationships. We are in communion. CRS has a long-term relationship with 15 partners, which donate a percentage of all related sales back to CRS for their continued work. These partners are committed to Fair Trade to the point that they are donating profit to help disadvantaged farmers and artisans, and are helping us by making products available. ! The non-profit Divine Chocolate and Equal Peace Coffee and company, SERRV, is Exchange are the CRS Providence Coffee are the craft partner. They chocolate partners. Divine two of the CRS coffee have an awesome Chocolate is owned by its partners. Peace is in catalog and website. members, a truly unique Mpls. and Providence is Artisan cooperatives situation in the cocoa based in Faribault. Both are certified, which growing world. They also have websites and also means that each own nearly half of the market through parishes individual product may processing operation. and other local markets. not bear the Fair Equal Exchange also sells Peace Coffee can often Trade label. -

Fairtrade – a Competitive Imperative? an Investigation to Understand the Role of Fair Trade in Company Strategy in the Chocolate Industry

Fairtrade – a Competitive Imperative? An Investigation to Understand the Role of Fair Trade in Company Strategy in the Chocolate Industry Master’s Thesis in Business Administration Author: Phuong Thao Tran & Elina Vettersand Tutor: Anna Blombäck Jönköping University May 2012 Master’s Thesis in Business Administration Title: Fairtrade - a Competitive Imperative? Author: Phuong Thao Tran & Elina Vettersand Tutor: Anna Blombäck Date: 2012 -05-14 Subject terms: Strategic entrepreneurship, fair trade, competitive advantage. Abstract Background: The rise in ethical consumerism has become evident through an increase in sales of fair trade products in recent years. Consumers are prepared to pay a premium for fair trade chocolate, and with a steady future growth in the fair trade movement, this is an attractive market for new entrants. Of particular focus are the Swedish and German markets for fair trade chocolate as they show promising growth rates and interest in this field. Problem: The chocolate industry is very competitive, and the observation that con- sumers reward companies that act socially responsible presents an oppor- tunity for ethical companies to compete. This is attractive for entrepreneuri- al firms, but there exist numerous motivations why firms choose to engage in fair trade. Purpose: The purpose of this thesis is to understand the role of fair trade in corpo- rate strategy (either in partial or entire assortment), its relation to entrepre- neurial opportunity-seeking behaviour, and examining how the strategic re- source of Fairtrade certification is used to gain competitive advantage. Method: A qualitative interview study was applied, and ten chocolate companies ac- tive in the Swedish and German markets were included in the sample. -

Why We LOVE Our Fair Trade Food Producers: OUR MISSION

Why we LOVE our fair trade food producers: OUR MISSION We create opportunities for artisans in developing countries to earn income by bringing their products and stories to our markets through long-term, fair trading relationships. 45% farmer owned created by a cocoa farmer co-op in Ghana with Our Fair Trade Promise the goal to empower farmers, increase women’s participation, and develop environmentally conscious coca Ten Thousand Villages is more than a rd cultivation. Over 1/3 of the farmers Equal Exchange works with store. We're a global maker-to-market are women who are empowered to movement that breaks the cycle of over 40 small famer organizations to have a greater say in their co-op and source product grown and processed generational poverty and ignites social communities. change. We're a way for you to shop in Africa, Asia, Latin America and the with intention for ethically-sourced Profits allow farmers to make US. Long standing relationships with wares — and to share in the joy of a fair wage, build village schools, build these farmers allow Equal Exchange to empowering makers in ten thousand separate toilets for men and women, secure the best coffee and tea crops villages. and bicycle programs provide school purchased for a fair price. transportation in 57 districts. Innovative programs are As a pioneer of fair trade, (Bluffton is are the first fair trade store in the U.S.) we Divine cocoa beans developed in collaboration with the co- do business differently, putting people ethically grown and harvested then ops; clinics are built to care for and planet first. -

CMW41P001.Qxd

68,152 from July 2006 to December 2006 Tuesday, March 13, 2007 Wear your nose with pride this Friday, March 16 Advertising feature THE TOWN SEES RED! WARRINGTON is gearing up for another action- through a series of techniques and exercises guaran- playing at the Warrington-based school in bands of packed Red Nose Day this Friday, March 16. teed to make you feel good. up to 30 performers at a time. Novice students will And event organisers and fundraisers throughout Later you will be invited to participate in an evening be playing alongside the school’s more advanced the town have been doing their bit to back Comic workshop where you’ll even have the chance to take musicians with the ultimate aim of performing one Relief’s Big One. to the stage yourself or simply sit back and enjoy the million notes across the course of the day! The Pyramid and Parr Hall have announced the show. So if you’re a budding comedian, now’s your If you’re willing to travel a bit further afield, head Laughter Workshop to salute Red Nose Day in style. chance! While you’re there you can also relax and to The Printworks in Manchester for the third North Festivities begin with a lunchtime session that watch Red Nose Day’s live TV show on a big screen. West Comedy Classics screening. demonstrates the health-giving properties of laughter All it will cost you is a donation to Comic Relief. Manchester will also host ‘stand up and be Alternatively, take a visit to Gala counted’ – a 24 hour comedy event to be held at the Bingo in the Cockhedge Centre where Comedy Lounge at Opus. -

Transfair USA, Annual Report 2009 About Us

Making History TransFair USA, Annual Report 2009 About Us TransFair USA is a nonprofit, mission-driven organization that tackles social and environmental sustainability with an innovative, entrepreneurial approach. We are the leading independent, third-party certifier of Fair Trade products in the United States, and the only U.S. member of Fairtrade Labelling Organizations International (FLO). We license companies to display the Fair Trade Certified™ label on products that meet our strict international standards. These standards foster increased social and economic stability, lead- ing to stronger communities and better stewardship of the planet. Our goal is to dramatically improve the livelihoods of farmers, workers and their families around the world. Our Mission TransFair USA enables sustainable development and community empowerment by cultivating a more equitable global trade model that benefits farmers, workers, consumers, industry and the earth. We achieve this mission by certifying and promoting Fair Trade products. Letter from the President & CEO Contents Dear Friends, 04 2009 Accomplishments In 2009, the Fair Trade movement In 2009, we certified over 100 million As we move forward, we have renewed ushered in a new era. Our eleventh year pounds of coffee for the first time, more hope for economic recovery and of certifying Fair Trade products saw than was certified in our first seven continued growth in sales of Fair 06 Fair Trade Certified Apparel social consciousness emerge as a top years of business combined. We saw Trade products. This next phase of priority for consumers, and the numbers opportunities for farm workers broaden Fair Trade is just beginning, and the 08 Social Sustainability reflected it. -

BBC Outreach Corporate Responsibility Report 2007/08

1 BBC Corporate Responsibility Report 2007/08 BBC Corporate Responsibility Report 2007/08 2 Welcome Welcome to the BBC Corporate Responsibility Report produced by BBC Outreach. BBC Outreach’s work is about making the BBC’s commitment to our stakeholders stronger and more inclusive. It’s about making us a better business in the way we work and the way we impact and interact with communities and all those to whom we broadcast. Our report will demonstrate how outreach, corporate responsibility and partnership work directly supports the BBC’s six Public Purposes and is vital if we are to achieve them. It will also cover what the BBC does to ensure that our operations, including our impact on the environment, are managed in a responsible manner. We hope you find the content of this report interesting and welcome your feedback. Alec McGivan Head of BBC Outreach BBC Outreach Room 4171, White City, 201 Wood Lane, London W12 7TS T: 020 8752 6761 E: [email protected] BBC Corporate Responsibility Report 2007/08 3 ContentsContents Introduction 04 Citizenship 08 Learning 14 Creativity 18 Community 24 Global 31 Communications 36 Environment 41 Charity 47 Our business 54 Verification 62 4 4 Introduction BBC Corporate Responsibility Report 2007/08 Why should you read this report? This report is written for the many stakeholders who have an interest in the BBC. The BBC exists to serve the public, and has a responsibility to account to licence fee payers everywhere for its actions. “ The BBC’s role and remit is set out in its Royal Charter, established by Being” responsible the Government on behalf of the Crown and debated in Parliament. -

The Role of Social Capital in the Success of Fair Trade Abstract Key

Journal of Business Ethics, 2010, Volume 96, Number 2, Pages 317-338 The Role of Social Capital in the Success of Fair Trade Iain A. Davies and Lynette J. Ryals Abstract Fair Trade companies have pulled off an astonishing tour de force. Despite their relatively small size and lack of resources, they have managed to achieve considerable commercial success and, in so doing, have put the fair trade issue firmly onto industry agendas. We analyse the critical role played by social capital in this success and demonstrate the importance of values as an exploitable competitive asset. Our research raises some uncomfortable questions about whether fair trade has ‘sold out’ to the mainstream and whether these companies have any independent future or whether their ultimate success lies in the impact they have had on day-to-day trading behaviour. Key Words Fair trade, Fairtrade, Social capital, Networks, Business ethics, Corporate values 1 The Role of Social Capital in the Success of Fair Trade The fair trade movement sprang from an ideology of encouraging community development in some of the most deprived areas of the world (Brown, 1993). It is achieved through the “application, monitoring and enforcement of a fair trade supply agreement and code of conduct typically verified by an independent social auditing system” (Crane and Matten, 2004: p.333). Far from its public perception of being ‘almost like a charity’ (Mintel, 2004), many fair trade organisations are, in fact, profit-seeking organisations (****, 2003; Doherty and Tranchell, 2007; Moore, 2004; Nichols and Opal, 2005), perceiving that engagement in the commercial mainstream is an effective way of delivering the promised benefits to third world producers (although the way profits are organised and distributed within the supply chain may differ somewhat from traditional businesses) (Doherty and Tranchell, 2007; Golding and Peattie, 2005, Lowe and Davenport, 2005a and 2005b, Moore, Gibbon and Slack, 2006). -

Fairtrade Chocolate and Comic Relief

Page 1 of 1 Fairtrade chocolate and Comic Relief Comic Relief’s Dubble bar and Divine Chocolate are produced by Divine Chocolate, which is jointly owned by Kuapa Kokoo and Twin Trading (a British Fairtrade company), and is supported by Christian Aid. 1. Divine Chocolate buys cocoa for Divine and Dubble bars for a price which gives the farmers a fair return for their quality beans and a premium to be invested in activities and projects which benefit farmers and their communities. Kuapa Kokoo owns 45% of the shares in the company and has a direct say in how the company is run and a share of the profits. 2. Ethical shopping is a growing trend in the UK. Consumers are learning more and more about how farmers at the beginning of the trading chain don’t always get a fair deal, and that they can make a difference by choosing carefully. Companies like Cafédirect, the Co-op, Divine Chocolate, Equal Exchange, Oxfam trading, Liberation Nuts and Traidcraft, who all produce and sell fairly traded products, want to give people a chance to make a difference – so Fairtrade market products are competitively priced and widely available in the shops. 3. Since 1985 Comic Relief has raised £750 million with every penny donated by the public going to projects in the UK and in some of the poorest countries in the world. School students have played a vital role, with 65% of UK schools taking part in Red Nose day. Comic relief has produced many TV programmes and educational materials to help explain the issues that lie ‘behind the nose’. -

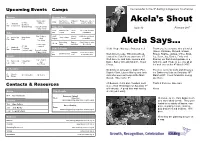

Akela Says... 6Th HQ 1:00 P.M

Upcoming Events Camps The newsletter for the 9th Barking & Dagenham Scout Group Beavers Beavers Only Doors Open Day Visit to Chigwell Please see Julie or 5 May 6th HQ 1:00 p.m. District Camp Row Leigh for further Akela’s Shout 3 Handcraft St. Mary’s Mar Competition Grafton Road Drop off exhibits Cubs Only Friday 8-9:30 Issue 92 February 2007 25-28 Whitsun Cub Thrift- £45 A set of forms Cubs May Camp wood is available 5 for 5:30 p.m. 18-25 Hesley £120 A set of forms 10 Swimming Dagenham Pack Holiday start August Wood is available Feb Gala Pool See Akela Swimming Dagen- 5 for 5:30 p.m. start 10 Feb Doors Open Gala ham Pool See Akela Akela Says... 6th HQ 1:00 p.m. 3 Handcraft St. Mary’s Mar Competition Cubs & Scouts Hi all, I hope this issue finds you well. Thank you to everyone who attended Grafton Road Drop off exhibits (Owen, Kristiano, Richard, Shawn, Friday 8-9:30 4-7 Chigwell £45 A set of forms District Camp May Row is available from Well done to Luke Willcocks who at- Shaun, Sophie, Joshua, Chloe, Brad- Scouts tended the Cub Chess and came 2nd. ley, Dean, Jay, Daniel, Emily and 5 for 5:30 p.m. Well done to Jack Avis, Gemma and Ronnie) our first church parade in a 10 Swimming Dagenham start Feb Gala Pool Daniel Bailey who attended the Scout long time and I hope to see you all at See Akela Chess. the next one on the 4th March 2007.