Team Goal Commitment and Team Effectiveness: the Role of Task Interdependence and Supportive Behaviors

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

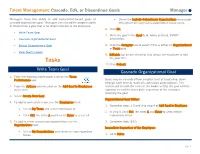

Manager Cascade, Edit, Or Discontinue Goal(S) in Workday

Talent Management: Cascade, Edit, or Discontinue Goals Manager Managers have the ability to add department-based goals or • Check the Include Subordinate Organizations to cascade cascade organization goal. Managers can also edit in-progress goals throughout all supervisory organization below yours. or discontinue a goal that is no longer relevant to the employee. 6. Click OK. • Write Team Goal 7. Write the goal in the Goal field. Add a detailed, SMART • Cascade Organizational Goal description. • Edit or Discontinue a Goal 8. Click the Category box to select if this is either an Organizational or Team goal. • View Team’s Goals 9. Editable will be pre-selected. This allows the employee to edit Tasks the goal title. 10. Click Submit. Write Team Goal Cascade Organizational Goal 1. From the Workday home page, click on the Team Performance app. Goals may be cascaded from a higher level of leadership, down through each level to reach all supervisory organizations. This 2. From the Actions column, click on the Add Goal to Employees section will include the steps of the leader writing the goal and the menu item. approval step of the immediate supervisor of the employee receiving the goal. 3. Select Create New Goal. Organizational Goal Writer: 4. To add to immediate team, use the Employees field: 1. Complete steps 1-3 and skip step 4 of Add Goal to Employee. • Select My Team and select individuals or 2. In step 5, click Ctrl, the letter A and Enter to select entire • Click Ctrl, the letter A and then hit Enter to select all. -

Chapter 6 – Group and Team Performance 90

Chapter 6 – Group and Team Performance 90 CHAPTER 6 – Group and Team Performance OBJECTIVES The major purpose of this chapter on group process and effectiveness is to introduce the student to ways to think about interacting groups so that they will become more effective members and leaders of them. Every student has had some experience with both social and task groups that they can call on as they study this topic. Our first objective in this chapter is to focus on how central these groups are to our lives. We also attempt to impress on the students that they will likely spend large proportions of their work hours in small group settings, because modern management appears to be making increasing use of teams or other small groups to solve problems, make decisions, and execute tasks. The next objective is to help student understand the many types of groups they may be involved with and how groups vary by purpose and organization. Another objective is to introduce students to a basic model of group effectiveness that includes influences from the environment within which the group operates. Environmental influences can have a critical impact on group effectiveness and the different types of influences are considered. At this point the chapter changes its focus to give more emphasis to internal group dynamics by covering such topics as cooperation and competition. Here, one objective is to introduce students to group development and the process by which groups become (or fail to become) mature. Another objective is to introduce the role of norms in influencing group member behavior. -

Shared Leadership Underpinning of the MLCF

Shared Leadership Underpinning of the MLCF A key product from the Enhancing Engagement in Medical Leadership project has been the development of a Medical Leadership Competency Framework (MLCF). This document defines the skills and competences needed by doctors to engage effectively in the planning, provision and improvement of health care services. It applies to all doctors and is intended to be acquired across the medical career at each appropriate level (Undergraduate, Postgraduate and Continuing Practice). It is therefore not aimed at specific, positional leaders but is seen as a set of competences that should be fully integrated into the medical role and not a separate function. The philosophical leadership model that underpins this approach is that of shared leadership, a more modern conception of leadership that departs from traditional charismatic or hierarchical models. In working with the MLCF it is useful to understand the shared leadership approach and this paper is an attempt to provide a simple description and guide to the shared leadership model, and to answer some of the questions about shared leadership that have been asked during the development of the MLCF: • What is shared leadership? • How does shared leadership underpin the MLCF? • How does shared leadership relate to positional leadership? • Where is the evidence that shared leadership works and what can we learn from other settings? • What evidence is there from health care and how do we apply shared leadership in a clinical setting? • What do the critics of shared leadership say? What is shared leadership? Leadership in any context has historically been described in relation to the behaviour of an individual and their relationship to their followers. -

Team Leadership Styles

Team Leadership Styles Leadership Skills Team FME www.free-management-ebooks.com ISBN 978-1-62620-988-6 Copyright Notice © www.free-management-ebooks.com 2013. All Rights Reserved ISBN 978-1-62620-988-6 The material contained within this electronic publication is protected under International and Federal Copyright Laws and treaties, and as such any unauthorized reprint or use of this material is strictly prohibited. You may not copy, forward, or transfer this publication or any part of it, whether in elec- tronic or printed form, to another person, or entity. Reproduction or translation of any part of this work without the permission of the copy- right holder is against the law. Your downloading and use of this eBook requires, and is an indication of, your complete acceptance of these ‘Terms of Use.’ You do not have any right to resell or give away part, or the whole, of this eBook. TEAM LEADERSHIP STYLES Table of Contents Preface 2 Visit Our Website 3 Introduction 4 Team Examples 6 Development Team Example 7 Customer Support Team Example 9 Steering Team Example 10 Leadership Theories 13 Early Trait Theories 13 Leadership for Management 16 Transactional Leadership 17 Applied to the Team Examples 19 Transformational Leadership 22 Applied to the Team Examples 24 Situational Leadership® 26 Applied to the Team Examples 28 The Leadership Continuum 30 Applying this Style to the Team Examples 32 Summary 34 Other Free Resources 35 References 36 ISBN 978-1-62620-988-6 © www.free-management-ebooks.com 1 TEAM LEADERSHIP STYLES Preface This eBook has been written for managers who find themselves in a team leadership role. -

Organizational Change and Development Chapter 12

Organizational Change and Development Chapter 12 ORGANIZATIONAL CHANGE AND DEVELOPMENT Introduction Change is a constant, a thread woven into the fabric of our personal and professional lives. Change occurs within our world and beyond -- in national and international events, in the physical environment, in the way organizations are structured and conduct their business, in political and socioeconomic problems and solutions, and in societal norms and values. As the world becomes more complex and increasingly interrelated, changes seemingly far away affect us. Thus, change may sometimes appear to occur frequently and randomly. We are slowly becoming aware of how connected we are to one another and to our world. Organizations must also be cognizant of their holistic nature and of the ways their members affect one another. The incredible amount of change has forced individuals and organizations to see “the big picture” and to be aware of how events affect them and vice versa. Organizational development (OD) is a field of study that addresses change and how it affects organizations and the individuals within those organizations. Effective organizational development can assist organizations and individuals to cope with change. Strategies can be developed to introduce planned change, such as team-building efforts, to improve organizational functioning. While change is a “given,” there are a number of ways to deal with change -- some useful, some not. Organizational development assists organizations in coping with the turbulent environment, both internally and externally, frequently doing so by introducing planned change efforts. Organizational development is a relatively new area of interest for business and the professions. While the professional development of individuals has been accepted and fostered by a number of organizations for some time, there is still ambiguity surrounding the term organizational development. -

Supported Employment Fidelity Review Manual

SUPPORTED EMPLOYMENT FIDELITY REVIEW MANUAL Deborah R. Becker Sarah J. Swanson Sandra L. Reese Gary R. Bond Bethany M. McLeman Copyright © 2008, 2015 by all original copyright holders. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the written permission of the rights holder. SUPPORTED EMPLOYMENT FIDELITY REVIEW MANUAL A companion guide to the evidence-based IPS Supported Employment Fidelity Scale Deborah R. Becker Sarah J. Swanson Sandra L. Reese Gary R. Bond Bethany M. McLeman Dartmouth Psychiatric Research Center Third Edition December, 2015 TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE .......................................................................................................................... iv INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................................. v Chapter 1: Introduction to IPS Supported Employment Fidelity .............................. 1 IPS Supported Employment Overview ........................................................................... 1 Overview of the IPS Supported Employment Fidelity Scale .......................................... 3 Sources of Information ............................................................................................... 5 What is Rated? ............................................................................................................ 5 Unit of Analysis ......................................................................................................... -

Groups & Teams

Organizational Behavior and Organizational Change Groups & Teams Roger N. Nagel Senior Fellow & Wagner Professor Lehigh University 1 CSE & Enterprise Systems Center Lehigh University Roger N. Nagel © 2006 Topics in this Presentation Why people join groups The Five-Stage Model of Group Development Group Structure: ¾ Conformity, Status, Cohesiveness Group - Decision Making e l e v e n t h e d i t i o n ¾ Group - Decision Making Techniques » Group think, Groupshift o r g a n i z a t i o n a l b e h a v i o r ¾ Interacting Groups ¾ Nominal Group Technique ¾ Brainstorming stephen p. robbins ¾ Electronic Meeting 2 Evaluating Group Effectiveness Why Have Teams Become So Popular? “Organizational“Organizational behavior” behavior” Team Versus Group: What’s the Difference EleventhEleventh Edition Edition ¾ Comparing Work Groups and Work Teams ByBy Steve Steve Robbins Robbins Types of Teams ISBNISBN 0-13-191435-9 0-13-191435-9 A Team-Effectiveness Model ReferenceReference Book Book Beware: Teams Aren’t Always the Answer 2 CSE & Enterprise Systems Center Lehigh University Roger N. Nagel © 2006 Groups A group is defined as two or more individuals ¾ Interacting and interdependent, ¾ who have come together to achieve particular objectives. Groups can be either formal or informal. Members similar or dissimilar 3 CSE & Enterprise Systems Center Lehigh University Roger N. Nagel © 2006 Why People Join Groups • Security • Status • Self-esteem • Affiliation • Power • Goal Achievement E X H I B I T 8–1 E X H I B I T 8–1 Page 239 Page 239 4 CSE & Enterprise Systems Center Lehigh University Roger N. -

Position-Specific Rugby Skills Handbook About This Handbook

POSITION-SPECIFIC RUGBY SKILLS HANDBOOK ABOUT THIS HANDBOOK Thank you for downloading the Ruck Science position-specifc rugby skills handbook. This handbook is designed for amateur rugby players, coaches and parents as a guide to creating tailored training programs that meet the needs of each individual position on a rugby team. The handbook will take readers through the specifc physical and technical demands of each position as well as the training associated with building the requisite skill set. We would like to use this opportunity to thank several organizations without whom this handbook would not have been possible. Firstly, the Canadian Rugby Union who created a similar guide in 2009. This version has drawn a lot of inspiration from that original work which was itself a derivative of a manual set up by the English Rugby Union. Secondly, the writing team of Tudor Bompa & Frederick Claro whose trans-formative work Periodization in Rugby was also published in 2009. “Periodization in Rugby” is, without a doubt, the most complete analysis of periodized training for amateur rugby players and should be essential reading for all rugby coaches who are working with young players. Sincerely, Tim Howard Founder Ruck Science TABLE OF CONTENTS 2. About this handbook 4. Physical preparation for rugby 5. Warming up 5. Cooling down 6. Key rugby skills 6. Healthy eating 7. Prop 15. Hooker 21. Lock 27. Flanker 36. Number 8 42. Scrumhalf 47. Flyhalf 52. Center 56. Wing 61. Fullback Riekert Hattingh SEATTLE SEAWOLVES RUGBY SHORTS WITH POCKETS The world’s most comfortable rugby shorts, with deep, strong pockets on both sides. -

Teams, Team Process, and Team Building

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons School of Business: Faculty Publications and Other Works Faculty Publications 2014 Teams, Team Process, and Team Building James W. Bishop Dow Scott Loyola University Chicago, [email protected] Stephanie Maynard-Patrick Lei Wang Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/business_facpubs Part of the Business Administration, Management, and Operations Commons, and the Performance Management Commons Recommended Citation Bishop, James W.; Scott, Dow; Maynard-Patrick, Stephanie; and Wang, Lei. Teams, Team Process, and Team Building. Clinical Laboratory Management, 2nd Edition, , : 373-391, 2014. Retrieved from Loyola eCommons, School of Business: Faculty Publications and Other Works, http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/ 9781555817282.ch18 This Book Chapter is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Publications at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in School of Business: Faculty Publications and Other Works by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. © ASM Press 2014 18 Introduction Teams, Team Process, Definition of a Team Distinguishing Teams from Work Groups • Types and Classifications of Teams • Why Define a “Team” So and Team Building Precisely? Group Process and Teams James W. Bishop, K. Dow Scott, Guidelines for Choosing Whether To Have Teams Stephanie Maynard-Patrick, and Lei Wang Common -

Here Are Some Easy Starter Tips for Teaching the Game of Tchoukball to Your PE Students

Here are some easy starter tips for teaching the game of Tchoukball to your PE students • Don’t tell them they can score at either rebounder. At first tell your teams they can only score at the opposite end. This will get them used to moving the ball up and down the court. You can add the both frame rule down the road. • Remember the rules of 3: 3 sec to hold the ball, only three steps, and when you are attacking both ends you cannot throw at the same rebounder after 3 trys. • When there is a change of possession make sure there is a “reset” by the new team. A reset is done by touching the ball to the floor with both hands on the ball. This can be done anywhere; it does not have to be at the goal line. • Don’t allow students to guard, intercept or even get in the way of a student who is trying to throw or catch a ball. No blocking out, screening, standing in the way of the rebounder is allowed. The team without the ball actually must make a concentrated effort to stay out of the way of the offensive team. • Once the ball leaves the hand of the team trying to score, they must now make sure they are not interfering with the other team trying to catch their ball. Any interference here is a foul and loss of possession/no score. • Small sided games are the best….3-5 players on a team. You can have a third team rotate in after a score. -

Team Leadership

The Leadership Quarterly 12 (2001) 451–483 Team leadership Stephen J. Zaccaroa,*, Andrea L. Rittmana, Michelle A. Marksb aPsychology Department, George Mason University, 3064 David T. Langehall, 4400 University Drive, Fairfax, VA 22030-4444, USA bFlorida International University, Miami, FL, USA Abstract Despite the ubiquity of leadership influences on organizational team performance and the large literatures on leadership and team/group dynamics, we know surprisingly little about how leaders create and handle effective teams. In this article, we focus on leader–team dynamics through the lens of ‘‘functional leadership.’’ This approach essentially asserts that the leader’s main job is to do, or get done, whatever functions are not being handled adequately in terms of group needs. We explicate this functional leadership approach in terms of 4 superordinate and 13 subordinate leadership dimensions and relate these to team effectiveness and a range of team processes. We also develop a number of guiding propositions. A key point in considering such relationships is the reciprocal influence, whereby both leadership and team processes influence each other. D 2002 Elsevier Science Inc. All rights reserved. 1. Introduction Effective team performance derives from several fundamental characteristics (Zaccaro & Klimoski, in press). First, team members need to successfully integrate their individual actions. They have specific and unique roles, where the performance of each role contributes to collective success. This means that the causes of team failure may reside not only in member inability, but also in their collective failure to coordinate and synchronize their individual contributions. Team processes become a critical determinant of team performance, and often mediate the influences of most other exogenous variables. -

Team Management & Leadership

Team Management & Leadership The Team Kata at the Heart of a High Performance Organization By Lawrence M. Miller All organizations are both technical and social systems. Most companies implementing lean management (Toyota Production System) have focused heavily on the technical system, improving processes, eliminating waste and work-in-process inventory. However, the two core pillars of lean are continuous improvement and respect for people. These two pillars are social or cultural principles and practices. You are not “lean” unless you have gone a long way toward implementing a culture of continuous improvement and respect for people. A “kata” is a discipline of practice, a term most commonly used in martial arts. There are indi- vidual katas and there are team katas. Every sports team practices disciplined, routine movements that are at the core of their success. In this article, I want to briefly describe this core practice of lean organizations. James P. Womack and his associates at MIT spent five years and five million dollars studying the differences between auto assembly plants in the U.S., Japan, and Europe to identify the key dif- ferences in the systems that were the cause of different levels of quality and productivity. “What are the truly important organizational features of a lean plant - the specific as- pects of plant operations that account for up to half of the overall performance differences among plants across the world? The truly lean plant has two key organizational features: It transfers the maximum number of tasks and responsibilities to those workers adding value to the car on the line, and it has in place a system for detecting defects that quickly traces every problem, once discovered, to its ultimate caus.