The Quest for Nagalim: Fault Lines and Challenges Pradeep Singh Chhonkar

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Naga Peace Talks

Naga Peace Talks drishtiias.com/printpdf/naga-peace-talks Why in News Recently, the Nagaland Government appealed to all Naga political groups and extremist groups to cooperate in establishing unity, reconciliation and peace in the region. The peace process between the central government and two sets of the Naga extremist groups has been delaying for more than 23 years. Nagas Nagas are a hill people who are estimated to number about 2.5 million (1.8 million in Nagaland, 0.6 million in Manipur and 0.1 million in Arunachal states) and living in the remote and mountainous country between the Indian state of Assam and Burma. There are also Naga groups in Burma. The Nagas are not a single tribe, but an ethnic community that comprises several tribes who live in the state of Nagaland and its neighbourhood. Nagas belong to the Indo-Mongoloid Family. There are nineteen major Naga tribes, namely, Aos, Angamis, Changs, Chakesang, Kabuis, Kacharis, Khain-Mangas, Konyaks, Kukis, Lothas (Lothas), Maos, Mikirs, Phoms, Rengmas, Sangtams, Semas, Tankhuls, Yamchumgar and Zeeliang. Key Points 1/4 Background of Naga Insurgency: The Naga Hills became part of British India in 1881. The effort to bring scattered Naga tribes together resulted in the formation of the Naga Club in 1918. The club aroused a sense of Naga nationalism. The club metamorphosed into the Naga National Council (NNC) in 1946. Under the leadership of Angami Zapu Phizo, the NNC declared Nagaland as an independent State on 14th August, 1947, and conducted a “referendum” in May 1951 to claim that 99.9% of the Nagas supported a “sovereign Nagaland”. -

Sebuah Kajian Pustaka

International Journal of Research in Social Sciences Vol. 8 Issue 7, July 2018, ISSN: 2249-2496 Impact Factor: 7.081 Journal Homepage: http://www.ijmra.us, Email: [email protected] Double-Blind Peer Reviewed Refereed Open Access International Journal - Included in the International Serial Directories Indexed & Listed at: Ulrich's Periodicals Directory ©, U.S.A., Open J-Gage as well as in Cabell‟s Directories of Publishing Opportunities, U.S.A Conflicts in Northeast India: Intra-state conflicts with reference to Assam Dharitry Borah Debotosh Chakraborty Abstract Conflict in Northeast India has a brand entity that entrenched country‟s name in the world affairs for decades. In this paper, an attempt was made to study the genesis of conflicts in Northeast India with special emphasis on the intra-state conflicts in Assam. Attempts Keywords: were also made to highlight reasons why Northeast India has Conflict; remained to be a highly conflict ridden area comparing to other parts Sovereignty; of India. The findings revealed that the state has continued to be a Separate homeland; hub for several intra-state conflicts – as some particular groups raised Indian State demand for a sovereign state, while some others are betrothed in demanding for a separate state or homeland. There exists a strong nexus between historical circumstances and their intertwined influence on the contemporary conflict situations in the State. For these deep-rooted influences, critical suggestions are incorporated in order to deal with the conflicts and to bring sustainable and long- lasting peace in the State. Ph.D. Candidate, Department of Political Science, Assam University, Silchar, Assam, India Assistant Professor, Department of Political Science, Assam University, Silchar, Assam, India 715 International Journal of Research in Social Sciences http://www.ijmra.us, Email: [email protected] ISSN: 2249-2496Impact Factor: 7.081 1. -

3. on April 9, 1946, the NNC Submitted a Memorandum to The

The 72nd anniversary of NNC formation Day. The Naga Club was formed in October 1918, and the same leaders renamed the Naga Club as the Naga National Council (NNC) on the 2nd February 1946 at Wokha Town, Nagaland, and the Naga Club leaders became the leaders of NNC. The aspiration of the leaders was to safeguard the sovereignty of Nagaland in those days of changing world. Today, the 2nd February 2018 is the 72nd anniversary of the NNC formation Day. The achievements and history of the NNC. 1. With the formation of the NNC, all the Naga Villages were brought into a nation for the first time in the Naga national history. Before the formation of the NNC, each and every Naga village was sovereign and republic in itself. 2. The NNC blatantly rejected the Couplan plan of the British Crown Colony for the Hill people of Frontier areas, which was proposed by Sir Robert Reid and Sir Reginald Coupland in 1946, and thus the plan became non-starter. 3. On April 9, 1946, the NNC submitted a memorandum to the British Cabinet Commission Camp New Delhi stating that “The Naga future would not be bound by arbitrary decision of the British Government. And any recommendation without consultation would not be accepted. We have not deviated from the true path of national independence. We shall not betray our nation.” 4. On 27th March, 1946, the Naga National Council sent a letter to Lord Simon, House of Lords, stated that “we the Nagas made it clear to your Lordship and your Lordship’s colleagues in 1929 that we desire to be left alone in the event of the British withdrawal from India. -

Quest for Nagalim: Mapping of Perceptions Outside Nagaland

Quest for Nagalim: Mapping of Perceptions Outside Nagaland Pradeep Singh Chhonkar Introduction The Nagas of Nagaland could always identify themselves with the Naga identity due to being in a state named after their own collective identity. However, the Naga tribes outside Nagaland, especially those of Manipur and Assam, always had a strong reason to reassert their Naga-ness. The response to the idea of a separate Nagalim has been wide-ranging across the entire region affected by Naga insurgency. A Framework Agreement was signed between the Government of India and the National Socialist Council of Nagaland (NSCN-IM) on August 03, 2015. The agreement affected four states and approximately 35 Naga and other ethnic tribes inhabiting the traditional Naga areas. The agreement set three crucial parameters for the detailed settlement. First, it recognised that the Naga ‘history and situation’ was unique. Second, it proposed that sovereign powers would be shared between the Centre and the Nagas through a division of competencies, that is, through renegotiating the Union, State and Concurrent Lists of competencies of the Indian Constitution. Third, the two sides would strive for a mutually acceptable and peaceful settlement. While details of the accord are still shrouded in secrecy, it has been indicated that there will be no modification to the state boundaries. There Brigadier Pradeep Singh Chhonkar SM, VSM, is former Research Fellow at IDSA and presently commanding a Brigade in Northeast India. 80 CLAWS Journal l Winter 2018 QUEST FOR NAGALIM are indications about facilitation of cultural integration of the Nagas through special measures, and provision of financial and administrative autonomy of the Naga dominated areas in other states. -

Survey of Conflicts & Resolution in India's Northeast

Survey of Conflicts & Resolution in India’s Northeast? Ajai Sahni? India’s Northeast is the location of the earliest and longest lasting insurgency in the country, in Nagaland, where separatist violence commenced in 1952, as well as of a multiplicity of more recent conflicts that have proliferated, especially since the late 1970s. Every State in the region is currently affected by insurgent and terrorist violence,1 and four of these – Assam, Manipur, Nagaland and Tripura – witness scales of conflict that can be categorised as low intensity wars, defined as conflicts in which fatalities are over 100 but less than 1000 per annum. While there ? This Survey is based on research carried out under the Institute’s project on “Planning for Development and Security in India’s Northeast”, supported by the Canadian International Development Agency (CIDA). It draws on a variety of sources, including Institute for Conflict Management – South Asia Terrorism Portal data and analysis, and specific State Reports from Wasbir Hussain (Assam); Pradeep Phanjoubam (Manipur) and Sekhar Datta (Tripura). ? Dr. Ajai Sahni is Executive Director, Institute for Conflict Management (ICM) and Executive Editor, Faultlines: Writings on Conflict and Resolution. 1 Within the context of conflicts in the Northeast, it is not useful to narrowly define ‘insurgency’ or ‘terrorism’, as anti-state groups in the region mix in a wide range of patterns of violence that target both the state’s agencies as well as civilians. Such violence, moreover, meshes indistinguishably with a wide range of purely criminal actions, including drug-running and abduction on an organised scale. Both the terms – terrorism and insurgency – are, consequently, used in this paper, as neither is sufficient or accurate on its own. -

Review of Research

Review Of ReseaRch impact factOR : 5.7631(Uif) UGc appROved JOURnal nO. 48514 issn: 2249-894X vOlUme - 8 | issUe - 7 | apRil - 2019 __________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ AN ANALYSIS OF THE AUTONOMY MOVEMENT OF HILL TRIBES OF ASSAM Ishani Senapoti Research Scholar, Department of Political Science Gauhati University, Guwahati, Assam, India. ABSTRACT : Movements for Autonomy have marked the political discourse in Northeast India for the last decades. The aim and purpose of the autonomy movement is not only to bring about change in the existing system but also to augment legitimate expressions of aspirations by the people having a distinct culture, tradition and common pattern of living. In the post colonial period, Assam which is a land of diverse ethnic communities has witnessed a serious of autonomy movements based on the political demands for statehood. The autonomy movement of the Hill Tribals in North East India in general and North Cachar Hills District and Karbi Anglong District of Assam in particular is a continuous effort and struggle of the Hill Tribal to protect and preserve their distinct identity, culture and tradition and to bring about a change in the existing socio-political arrangement. Although the Sixth Schedule of the Indian Constitution has provided for Autonomous Councils in these two districts but much improvement could not be achieved due to limited power of the Autonomous District Council and the State government’s apathy. Their demand for an autonomous state is rooted in the long history of similar movements in the north east and has been demanding a separate state for the Dimasas and the Karbis in the name of ‘Dimaraji’ for Dimasas and ‘Hemprek’ for Karbis. -

Centre for North East Studies and Policy Research Jamia Millia Islamia New Delhi 110 025 Panel Discussion on 'Understanding Th

Centre for North East Studies and Policy Research Jamia Millia Islamia New Delhi 110 025 Panel Discussion on ‘Understanding the Naga Peace Talks: The ways forward’ 28 September, 2020, from 2 PM onwards Join with Google Meet: meet.google.com/xoa-ucuk-jjg A Background Note The Naga movement for independence started around the time India won independence. The first ever peace building effort was made as early as in June 1947 through an agreement between the then Governor of Assam and the Naga National Council. The effort however failed to have any meaningful impact. Thereafter, the Naga National Council declared independence and claimed to have conducted a plebiscite for independence. The government was willing to give limited autonomy under the constitution of the country. The Nagas rejected the offer and boycotted the first parliamentary elections held in 1951. In 1959, the Naga People’s Convention adopted a resolution for the formation of a separate state. This led to the Sixteen-Point agreement to elevate Naga Hills-Tuensang Areas into a state known as Nagaland. But, the creation of Nagaland could not bring peace. Another agreement, popularly known as the Shillong accord, was signed in 1975 between the Government of India and the “Representative of the Underground Organisations”. It created a major rift within the Naga National Council which ultimately led to its split in 1980 with the formation of the National Socialist Council of Nagaland. Meanwhile, a ceasefire came into being in 1997 between the Government of India and the NSCN-IM, and separately with the Khaplang-led NSCN faction since 2001. -

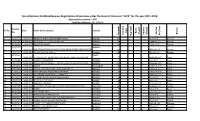

Fee Collections for Miscellaneous Registration of Societies Under The

Fee collections for Miscellaneous Registration of Societies under the Head of Accounts "1475" for the year 2017-2018 Applications recieved = 1837 Total fee collected = Rs. 2,20,541 Receipt Sl. No. Date Name of the Society District No. Copy Name Name Branch Change Change Challan Address Renewal Certified No./Date Duplicate 1 02410237 01-04-2017 NABAJYOTI RURAL DEVELOPMENT SOCIETY Barpeta 200 640/3-3-17 Barpeta 2 02410238 01-04-2017 MISSION TO THE HEARTS OF MILLION Barpeta 130 10894/28-3-17 Barpeta 3 02410239 01-04-2017 SEVEN STAR SOCIETY Barpeta 200 2935/9-3-17 Barpeta 02410240 Barpeta 4 01-04-2017 SIPNI SOCIO ECONOMIC AND CULTURAL DEVELOPMENT ORGANISATION 100 5856/15-2-17 Barpeta 5 02410241 01-04-2017 DESTINY WELFARE SOCIETY Barpeta 100 5857/15-2-17 Barpeta 08410259 Dhubri 6 01-04-2017 DHUBRI DISTRICT ENGINE BOAT (BAD BADHI) OWNER ASSOCIATION 75 14616/29-3-17 Dispur 7 15411288 03-04-2017 SOCIETY FOR CREATURE KAM(M) 52 40/3-4-17 Dispur 8 15411289 03-04-2017 MANAGEMENT COMMITTEE DAKHIN GUWAHATI JATIYA BIDYALAYA KAM(M) 125 15032/30-2-17 Dispur 9 24410084 03-04-2017 UNNATI SIVASAGAR 100 11384/15-3-17 Dispur 10 27410050 03-04-2017 AMGULI GAON MICRO WATERSHED COMMITTEE Udalguri 75 11836/16-2-17 Dispur 11 27410051 03-04-2017 MANPUR MICRO WATERSHED COMMITTEE Udalguri 75 11837/15-2-17 Dispur 12 27410052 03-04-2017 ULUBARI MICRO WATERSHED COMMITTEE Udalguri 75 11835/16-2-17 Dispur 13 15411291 04-04-2017 ST. CLARE CONVENT EDUCATIONAL SOCIETY KAM(M) 100 342/5-4-17 Dispur 14 16410228 04-04-2017 SERAPHINA SEVA SAMAJ KAM(R) 60 343/5-4-17 Dispur 15 16410234 -

Vol.VI, No.II, July-December, 2018

Volume: VI, Number: II July - December, 2018 ISSN: 2319-8192 Intellection $%LDQQXDO,QWHUGLVFLSOLQDU\5HVHDUFK-RXUQDO Editorial Board Chief Editor: Prof. Nikunja Bihari Biswas, Former Dean, Ashutosh Mukharjee School of Educational Sciences, Assam University, Silchar Editor Managing Editor Dr.Baharul Islam Laskar , Dr. Abul Hassan Chaudhury Principal , Assistant Registrar, M.C.D College, Sonai, Cachar Assam University, Silchar Associate Editors Dr. S.M.Alfarid Hussain, Dr. Anindya Syam Choudhury, Assistant Professor, Department of Mass Associate Professor, Department of English, Communication, Assam University, Silchar Assam University, Silchar Assistant Managing Editors Dr. Monjur Ahmed Laskar, Dr. Nijoy Kr Paul Research Associate, Professional Assistant, Central Library, Bioinformatics Centre, Assam University, Assam University, Silchar EDITORIAL BOARD MEMBERS Dr. Humayun Bokth , Prof J.U Ahmed , Associate Professor, Department of Sociology, Department of Management, NEHU, Assam University Tura Campus Dr. Merina Islam, (founder Editor), Dr. Pius V.T, Associate Professor, Department of Assistant Professor, Department of Philosophy, Philosophy , Cachar College, Silchar Assam University, Silchar Dr. Kh Narendra Singh, Prof Sk Jasim Uddin, Head, Department of Anthropology, Department of Chemistry, Assam University, Assam University, Diphu Campus Silchar Dr.Himadri Sekhar Das , Dr. Debotosh Chakraborty Assistant Professor, Department of Physics, Assistant Professor, Department of Political Assam university, Silchar Science, Assam University, Silchar Dr. Moynul Hoque, Dr. Md. Aynul Hoque, Assistant professor, Department of History, Former Assistant Professor, Gurucharan College, Silchar NERIE, Shillong Dr. Taj Uddin Khan Dr. Subrata Sinha, Assistant Professor, Deptt.of Botany, System Analyst, Computer Centre, S.S.College, Hailakandi Assam University, Silchar Dr. Ayesha Afsana Dr. Ganesh Nandi Former Guest Faculty, Deptt. of Law, Asstt. Professor, Deptt. -

Greater Nagalim” Economically Viable and Sustainable?

IS INDEPENDENT “GREATER NAGALIM” ECONOMICALLY VIABLE AND SUSTAINABLE? A. S. VAREKAN HoD Dept. Of Economics, Spicer Adventist University Pune (MS) INDIA The conglomerate Naga tribes and sub-tribes have been fighting for freedom and motherland during the British rule and in Independent India. They took to arms to this cause in Independent India and have always been that way since. The armed struggle movement have seen many drastic changes in the organization, leadership and demand but the ultimate goal of bringing all the Naga inhabited areas under one administration have stood the test of time. “Nagalim” is a term that denotes the demand for one administration of all the Naga inhabited areas which presently falls under four North-eastern states of Assam, Arunachal Pradesh, Manipur and Nagaland. The demand for Nagalim ranges from greater autonomy to complete independent nation. This paper examines whether it is economical viable and sustainable if the aspiration of an independent nation comes true or if not should it look for some other alternative which may be socially, economically and politically viable in the interest of all stakeholders. Key Words: Naga Club, NNC, NSCN, NSCN (I-M), NSCN (K), Nagalim, resources, Ceasefire, Framework Agreement INTRODUCTION: Nagaland was created as one of the Indian state in 1963. It was carved out of Assam to satisfy one of the long standing demands of the Naga people to be independent and free. One of the reasons could also have been the fallout of the Hydari Agreement and the armed struggle of the Naga insurgent movement. A. S. VAREKAN 1P a g e How did the Nagas of the present derived this acronym is still a topic of debate and have many theories. -

Naga Identity: Naga Nation As an Imagined Communities

International Journal of Research in Social Sciences Vol. 8 Issue 2, February 2018, ISSN: 2249-2496 Impact Factor: 7.081 Journal Homepage: http://www.ijmra.us, Email: [email protected] Double-Blind Peer Reviewed Refereed Open Access International Journal - Included in the International Serial Directories Indexed & Listed at: Ulrich's Periodicals Directory ©, U.S.A., Open J-Gage as well as in Cabell‟s Directories of Publishing Opportunities, U.S.A Naga Identity: Naga Nation as an Imagined Communities Longkoi Khiam* T.Longkoi Khiamniungan* Abstract Nationalism, as a political phenomenon, has gained much currency in the last few centuries. It has aroused large collectives of people and has become the grounds on which economic, cultural and political claims have been made. The nation has also become a marker of identity for individuals and whole societies. In this paper, I would like to look at the beginnings and formation of Naga nationalism and the important economic, cultural and political claims it makes. The beginnings of Naga nationalism could be located in the specific encounter Nagas had with modernity via British administrators and missionaries. From the 1940s onwards, the claims made by Naga nationalism have been met with certain ideological and militarist response from the Indian state. The response of the Indian state has determined the subsequent efforts of the Nagas to define the contours of their nationalism. Key words: Nationalism, nation, Naga identity, political, imagined communities, Nagaland, India, Indian response * Assistant Professor, Central University of Haryana 637 International Journal of Research in Social Sciences http://www.ijmra.us, Email: [email protected] ISSN: 2249-2496 Impact Factor: 7.081 Introduction As identities are mobilized to serve the political designs of vested interests, it seems obvious that the idea of a Naga nation and behind the „national liberation‟ and „secessionist‟ movements in the region is seemingly at least, incompatible with the idea of the Indian 'nation state'. -

Naga Peace Talks

Naga Peace Talks drishtiias.com/printpdf/naga-peace-talks Why in News Recently, the Nagaland Government appealed to all Naga political groups and extremist groups to cooperate in establishing unity, reconciliation and peace in the region. The peace process between the central government and two sets of the Naga extremist groups has been delaying for more than 23 years. Nagas Nagas are a hill people who are estimated to number about 2.5 million (1.8 million in Nagaland, 0.6 million in Manipur and 0.1 million in Arunachal states) and living in the remote and mountainous country between the Indian state of Assam and Burma. There are also Naga groups in Burma. The Nagas are not a single tribe, but an ethnic community that comprises several tribes who live in the state of Nagaland and its neighbourhood. Nagas belong to the Indo-Mongoloid Family. There are nineteen major Naga tribes, namely, Aos, Angamis, Changs, Chakesang, Kabuis, Kacharis, Khain-Mangas, Konyaks, Kukis, Lothas (Lothas), Maos, Mikirs, Phoms, Rengmas, Sangtams, Semas, Tankhuls, Yamchumgar and Zeeliang. Key Points 1/4 Background of Naga Insurgency: The Naga Hills became part of British India in 1881. The effort to bring scattered Naga tribes together resulted in the formation of the Naga Club in 1918. The club aroused a sense of Naga nationalism. The club metamorphosed into the Naga National Council (NNC) in 1946. Under the leadership of Angami Zapu Phizo, the NNC declared Nagaland as an independent State on 14th August, 1947, and conducted a “referendum” in May 1951 to claim that 99.9% of the Nagas supported a “sovereign Nagaland”.