Mesoscopic Fractional Quantum in Soft Matter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Motion and Time Study the Goals of Motion Study

Motion and Time Study The Goals of Motion Study • Improvement • Planning / Scheduling (Cost) •Safety Know How Long to Complete Task for • Scheduling (Sequencing) • Efficiency (Best Way) • Safety (Easiest Way) How Does a Job Incumbent Spend a Day • Value Added vs. Non-Value Added The General Strategy of IE to Reduce and Control Cost • Are people productive ALL of the time ? • Which parts of job are really necessary ? • Can the job be done EASIER, SAFER and FASTER ? • Is there a sense of employee involvement? Some Techniques of Industrial Engineering •Measure – Time and Motion Study – Work Sampling • Control – Work Standards (Best Practices) – Accounting – Labor Reporting • Improve – Small group activities Time Study • Observation –Stop Watch – Computer / Interactive • Engineering Labor Standards (Bad Idea) • Job Order / Labor reporting data History • Frederick Taylor (1900’s) Studied motions of iron workers – attempted to “mechanize” motions to maximize efficiency – including proper rest, ergonomics, etc. • Frank and Lillian Gilbreth used motion picture to study worker motions – developed 17 motions called “therbligs” that describe all possible work. •GET G •PUT P • GET WEIGHT GW • PUT WEIGHT PW •REGRASP R • APPLY PRESSURE A • EYE ACTION E • FOOT ACTION F • STEP S • BEND & ARISE B • CRANK C Time Study (Stopwatch Measurement) 1. List work elements 2. Discuss with worker 3. Measure with stopwatch (running VS reset) 4. Repeat for n Observations 5. Compute mean and std dev of work station time 6. Be aware of allowances/foreign element, etc Work Sampling • Determined what is done over typical day • Random Reporting • Periodic Reporting Learning Curve • For repetitive work, worker gains skill, knowledge of product/process, etc over time • Thus we expect output to increase over time as more units are produced over time to complete task decreases as more units are produced Traditional Learning Curve Actual Curve Change, Design, Process, etc Learning Curve • Usually define learning as a percentage reduction in the time it takes to make a unit. -

On Soft Matter

FASCINATING Research Soft MATTER Hard Work on Soft Matter What do silk blouses, diskettes, and the membranes of living cells have in common? All three are made barked on an unparalleled triumphal between the ordered structure of building blocks.“ And Prof. Helmuth march. Even information, which to- solids and the highly disordered gas. Möhwald, director of the “Interfaces” from soft matter: if individual molecules are observed, they appear disordered, however, on a larger, day frequently tends to be described These are typically supramolecular department at the MPIKG adds, “To as one of the most important raw structures and colloids in liquid me- supramolecular scale, they form ordered structures. Disorder and order interact, thereby affecting the put it in rather simplified terms, soft materials, can only be generated, dia. Particularly complex examples matter is unusual because its struc- properties of the soft material. At the MAX PLANCK INSTITUTES FOR POLYMER RESEARCH stored, and disseminated on a mas- occur in the area of biomaterials,” ture is determined by several weaker sive scale via artificial soft materials. says Prof. Reinhard Lipowsky, direc- forces. For this reason, its properties in Mainz and of COLLOIDS AND INTERFACES in Golm, scientists are focussing on this “soft matter”. Without light-sensitive coatings, tor of the “Theory” Division of the depend very much upon environ- there would be no microchip - and Max Plank Institute of Colloids and mental and production conditions.” nor would there be diskettes, CD- Interfaces in Golm near Potsdam The answers given by the three ROMs, and videotapes, which are all (MPIKG). Prof. Hans Wolfgang scientists are typical in that their made from coated plastics. -

1 the Principle of Wave–Particle Duality: an Overview

3 1 The Principle of Wave–Particle Duality: An Overview 1.1 Introduction In the year 1900, physics entered a period of deep crisis as a number of peculiar phenomena, for which no classical explanation was possible, began to appear one after the other, starting with the famous problem of blackbody radiation. By 1923, when the “dust had settled,” it became apparent that these peculiarities had a common explanation. They revealed a novel fundamental principle of nature that wascompletelyatoddswiththeframeworkofclassicalphysics:thecelebrated principle of wave–particle duality, which can be phrased as follows. The principle of wave–particle duality: All physical entities have a dual character; they are waves and particles at the same time. Everything we used to regard as being exclusively a wave has, at the same time, a corpuscular character, while everything we thought of as strictly a particle behaves also as a wave. The relations between these two classically irreconcilable points of view—particle versus wave—are , h, E = hf p = (1.1) or, equivalently, E h f = ,= . (1.2) h p In expressions (1.1) we start off with what we traditionally considered to be solely a wave—an electromagnetic (EM) wave, for example—and we associate its wave characteristics f and (frequency and wavelength) with the corpuscular charac- teristics E and p (energy and momentum) of the corresponding particle. Conversely, in expressions (1.2), we begin with what we once regarded as purely a particle—say, an electron—and we associate its corpuscular characteristics E and p with the wave characteristics f and of the corresponding wave. -

Soft Matter Theory

Soft Matter Theory K. Kroy Leipzig, 2016∗ Contents I Interacting Many-Body Systems 3 1 Pair interactions and pair correlations 4 2 Packing structure and material behavior 9 3 Ornstein{Zernike integral equation 14 4 Density functional theory 17 5 Applications: mesophase transitions, freezing, screening 23 II Soft-Matter Paradigms 31 6 Principles of hydrodynamics 32 7 Rheology of simple and complex fluids 41 8 Flexible polymers and renormalization 51 9 Semiflexible polymers and elastic singularities 63 ∗The script is not meant to be a substitute for reading proper textbooks nor for dissemina- tion. (See the notes for the introductory course for background information.) Comments and suggestions are highly welcome. 1 \Soft Matter" is one of the fastest growing fields in physics, as illustrated by the APS Council's official endorsement of the new Soft Matter Topical Group (GSOFT) in 2014 with more than four times the quorum, and by the fact that Isaac Newton's chair is now held by a soft matter theorist. It crosses traditional departmental walls and now provides a common focus and unifying perspective for many activities that formerly would have been separated into a variety of disciplines, such as mathematics, physics, biophysics, chemistry, chemical en- gineering, materials science. It brings together scientists, mathematicians and engineers to study materials such as colloids, micelles, biological, and granular matter, but is much less tied to certain materials, technologies, or applications than to the generic and unifying organizing principles governing them. In the widest sense, the field of soft matter comprises all applications of the principles of statistical mechanics to condensed matter that is not dominated by quantum effects. -

Newtonian Mechanics Is Most Straightforward in Its Formulation and Is Based on Newton’S Second Law

CLASSICAL MECHANICS D. A. Garanin September 30, 2015 1 Introduction Mechanics is part of physics studying motion of material bodies or conditions of their equilibrium. The latter is the subject of statics that is important in engineering. General properties of motion of bodies regardless of the source of motion (in particular, the role of constraints) belong to kinematics. Finally, motion caused by forces or interactions is the subject of dynamics, the biggest and most important part of mechanics. Concerning systems studied, mechanics can be divided into mechanics of material points, mechanics of rigid bodies, mechanics of elastic bodies, and mechanics of fluids: hydro- and aerodynamics. At the core of each of these areas of mechanics is the equation of motion, Newton's second law. Mechanics of material points is described by ordinary differential equations (ODE). One can distinguish between mechanics of one or few bodies and mechanics of many-body systems. Mechanics of rigid bodies is also described by ordinary differential equations, including positions and velocities of their centers and the angles defining their orientation. Mechanics of elastic bodies and fluids (that is, mechanics of continuum) is more compli- cated and described by partial differential equation. In many cases mechanics of continuum is coupled to thermodynamics, especially in aerodynamics. The subject of this course are systems described by ODE, including particles and rigid bodies. There are two limitations on classical mechanics. First, speeds of the objects should be much smaller than the speed of light, v c, otherwise it becomes relativistic mechanics. Second, the bodies should have a sufficiently large mass and/or kinetic energy. -

D0tc00217h4.Pdf

Electronic Supplementary Material (ESI) for Journal of Materials Chemistry C. This journal is © The Royal Society of Chemistry 2020 Electronic Supporting Information What is the role of planarity and torsional freedom for aggregation in a -conjugated donor-acceptor model oligomer? Stefan Wedler1, Axel Bourdick2, Stavros Athanasopoulos3, Stephan Gekle2, Fabian Panzer1, Caitlin McDowell4, Thuc-Quyen Nguyen4, Guillermo C. Bazan5, Anna Köhler1,6* 1 Soft Matter Optoelectronics, Experimentalphysik II, University of Bayreuth, Bayreuth 95440, Germany. 2Biofluid Simulation and Modeling, Theoretische Physik VI, Universität Bayreuth, Bayreuth 95440, Germany 3Departamento de Física, Universidad Carlos III de Madrid, Avenida Universidad 30, 28911 Leganés, Madrid, Spain. 4Center for Polymers and Organic Solids, Departments of Chemistry & Biochemistry and Materials, University of California, Santa Barbara 5Departments of Chemistry and Chemical Engineering, National University of Singapore, Singapore, 119077 6Bayreuth Institute of Macromolecular Research (BIMF) and Bavarian Polymer Institute (BPI), University of Bayreuth, 95440 Bayreuth, Germany. *e-mail: [email protected] 1 1 Simulated spectra Figure S1.1: Single molecule TD-DFT simulated absorption spectra at the wB97XD/6-31G** level for the TT and CT molecules. TT absorption at the ground state twisted cis and trans configurations is depicted. Vertical transition energies have been broadened by a Gaussian function with a half-width at half-height of 1500cm-1. Figure S1.2: Simulated average CT aggregate absorption spectrum. The six lowest vertical transition transition energies for CT dimer configurations taken from the MD simulations have been computed with TD-DFT at the wB97XD/6-31G** level. Vertical transition energies have been broadened by a Gaussian function with a half-width at half-height of 1500cm-1. -

Cell Biology Befriends Soft Matter Physics Phase Separation Creates Complex Condensates in Eukaryotic Cells

technology feature Cell biology befriends soft matter physics Phase separation creates complex condensates in eukaryotic cells. To study these mysterious droplets, many disciplines come together. Vivien Marx n many cartoons, eukaryotic cells have When the right contacts are made, phase a tidy look. A taut membrane surrounds separation occurs. Ia placid, often pastel-hued lake with well-circumscribed organelles such as Methods multitude ribosomes and a few bits and bobs. It’s a In the young condensate field, Amy helpful simplification of the jam-packed Gladfelter of the University of North cytoplasm. In some areas, there’s even more Carolina at Chapel Hill says her lab intense milling about1–4. To get a sense of intertwines molecular-biology-based these milieus, head to the kitchen with approaches, modeling, and in vitro Tony Hyman of the Max Planck Institute reconstitution experiments using simplified of Molecular Cell Biology and Genetics systems. “You can’t build models that have and Christoph Weber and Frank Jülicher of all the parameters that exist in a cell,” she the Max Planck Institute for the Physics of says. But researchers need to consider that Complex Systems, who note5: “For instance, in vitro work or overexpressing proteins when you make vinaigrette and leave it, you will not do complete justice to condensates come back annoyed to find that the oil and in situ. “Anything will phase separate vinegar have demixed into two different in a test tube,” she says, highlighting phases: an oil phase and a vinegar phase.” Just Eukaryotic cells contain mysterious, malleable, experiments in which crowding agents as oil and vinegar can separate into two stable liquid-like condensates in which there is intense such as polyethylene glycol are used to phases, such liquid–liquid phase separation activity. -

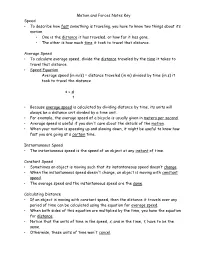

Motion and Forces Notes Key Speed • to Describe How Fast Something Is Traveling, You Have to Know Two Things About Its Motion

Motion and Forces Notes Key Speed • To describe how fast something is traveling, you have to know two things about its motion. • One is the distance it has traveled, or how far it has gone. • The other is how much time it took to travel that distance. Average Speed • To calculate average speed, divide the distance traveled by the time it takes to travel that distance. • Speed Equation Average speed (in m/s) = distance traveled (in m) divided by time (in s) it took to travel the distance s = d t • Because average speed is calculated by dividing distance by time, its units will always be a distance unit divided by a time unit. • For example, the average speed of a bicycle is usually given in meters per second. • Average speed is useful if you don't care about the details of the motion. • When your motion is speeding up and slowing down, it might be useful to know how fast you are going at a certain time. Instantaneous Speed • The instantaneous speed is the speed of an object at any instant of time. Constant Speed • Sometimes an object is moving such that its instantaneous speed doesn’t change. • When the instantaneous speed doesn't change, an object is moving with constant speed. • The average speed and the instantaneous speed are the same. Calculating Distance • If an object is moving with constant speed, then the distance it travels over any period of time can be calculated using the equation for average speed. • When both sides of this equation are multiplied by the time, you have the equation for distance. -

Gravity, Orbital Motion, and Relativity

Gravity, Orbital Motion,& Relativity Early Astronomy Early Times • As far as we know, humans have always been interested in the motions of objects in the sky. • Not only did early humans navigate by means of the sky, but the motions of objects in the sky predicted the changing of the seasons, etc. • There were many early attempts both to describe and explain the motions of stars and planets in the sky. • All were unsatisfactory, for one reason or another. The Earth-Centered Universe • A geocentric (Earth-centered) solar system is often credited to Ptolemy, an Alexandrian Greek, although the idea is very old. • Ptolemy’s solar system could be made to fit the observational data pretty well, but only by becoming very complicated. Copernicus’ Solar System • The Polish cleric Copernicus proposed a heliocentric (Sun centered) solar system in the 1500’s. Objections to Copernicus How could Earth be moving at enormous speeds when we don’t feel it? . (Copernicus didn’t know about inertia.) Why can’t we detect Earth’s motion against the background stars (stellar parallax)? Copernicus’ model did not fit the observational data very well. Galileo • Galileo Galilei - February15,1564 – January 8, 1642 • Galileo became convinced that Copernicus was correct by observations of the Sun, Venus, and the moons of Jupiter using the newly-invented telescope. • Perhaps Galileo was motivated to understand inertia by his desire to understand and defend Copernicus’ ideas. Orbital Motion Tycho and Kepler • In the late 1500’s, a Danish nobleman named Tycho Brahe set out to make the most accurate measurements of planetary motions to date, in order to validate his own ideas of planetary motion. -

The Von Neumann/Stapp Approach

4. The von Neumann/Stapp Approach Von Neumann quantum theory is a formulation in which the entire physical universe, including the bodies and brains of the conscious human participant/observers, is represented in the basic quantum state, which is called the state of the universe. The state of a subsystem, such as a brain, is formed by averaging (tracing) this basic state over all variables other than those that describe the state of that subsystem. The dynamics involves three processes. Process 1 is the choice on the part of the experimenter about how he will act. This choice is sometimes called “The Heisenberg Choice,” because Heisenberg emphasized strongly its crucial role in quantum dynamics. At the pragmatic level it is a “free choice,” because it is controlled, at least in practice, by the conscious intentions of the experimenter/participant, and neither the Copenhagen nor von Neumann formulations provide any description of the causal origins of this choice, apart from the mental intentions of the human agent. Each intentional action involves an effort that is intended to result in a conceived experiential feedback, which can be an immediate confirmation of the success of the action, or a delayed monitoring the experiential consequences of the action. Process 2 is the quantum analog of the equations of motion of classical physics. As in classical physics, these equations of motion are local (i.e., all interactions are between immediate neighbors) and deterministic. They are obtained from the classical equations by a certain quantization procedure, and are reduced to the classical equations by taking the classical approximation of setting to zero the value of Planck’s constant everywhere it appears. -

Kinematics Definition: (A) the Branch of Mechanics Concerned with The

Chapter 3 – Kinematics Definition: (a) The branch of mechanics concerned with the motion of objects without reference to the forces that cause the motion. (b) The features or properties of motion in an object, regarded in such a way. “Kinematics can be used to find the possible range of motion for a given mechanism, or, working in reverse, can be used to design a mechanism that has a desired range of motion. The movement of a crane and the oscillations of a piston in an engine are both simple kinematic systems. The crane is a type of open kinematic chain, while the piston is part of a closed four‐bar linkage.” Distinguished from dynamics, e.g. F = ma Several considerations: 3.2 – 3.2.2 How do wheels motions affect robot motion (HW 2) 3.2.3 Wheel constraints (rolling and sliding) for Fixed standard wheel Steered standard wheel Castor wheel Swedish wheel Spherical wheel 3.2.4 Combine effects of all the wheels to determine the constraints on the robot. “Given a mobile robot with M wheels…” 3.2.5 Two examples drawn from 3.2.4: Differential drive. Yields same result as in 3.2 (HW 2) Omnidrive (3 Swedish wheels) Conclusion (pp. 76‐77): “We can see from the preceding examples that robot motion can be predicted by combining the rolling constraints of individual wheels.” “The sliding constraints can be used to …evaluate the maneuverability and workspace of the robot rather than just its predicted motion.” 3.3 Mobility and (vs.) Maneuverability Mobility: ability to directly move in the environment. -

Soft Matter Research at Upenn Organize Anisotropic Bullet Shaped Particles Into 1D Chains 2D Hexag- Onal Structures (3)

Marquee goes here Soft Matter Research at UPenn organize anisotropic bullet shaped particles into 1D chains 2D hexag- onal structures (3). They have also shown that controlling boundary conditions and particle shape can allow the creation of hybrid washers which combine homeotropic and degenerate planar anchoring (4). The washers change their angle with respect to the far-field direction and are capable of trapping spherical colloids, allowing for the construc- tion of multi-shape colloidal assem- blages. These methods can be used to create complex shapes, further in- creasing the number of techniques Background image: An illustration of edge-pinning effect of focal conic domains (FCDs) in smectic-A liquid crystals available to those involved in creat- with nonzero eccentricity on short, circular pillars in a square array, together with surface topography and cross-polarized optical image of four FCDs on each pillar. The arrangement of FCDs is strongly influenced by the height and shape of the ing complex structures. pillars. Image courtesy of Felice Macera, Daniel Beller, Apiradee Honglawan, and Simon Copar. Advanced Materials Cover: This paper demonstrated an epitaxial approach to tailor the size and symmetry of toric focal conic domain (TFCD) arrays over large areas by exploiting 3D confinement and directed growth of Smectic-A liquid The team is actively contributing crystals with variable dimensions much like the FCDs. to the goals of the MRSEC by ex- panding the techniques available At the Materials Research Science The coalition has published sev- for use in the construction of com- & Engineering Center (MRSEC) at eral papers together. They have plex assemblies.