INVESTIGATION of STRUCTURAL EFFECTS on the AC MAGNETIC PROPERTIES of IRON OXIDE NANOPARTICLES by ERIC C. ABENOJAR Submitted in P

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Iron (III) Oxide Anhydrous

Material Safety Data Sheet Iron (III) Oxide Anhydrous MSDS# 11521 Section 1 - Chemical Product and Company Identification MSDS Name: Iron (III) Oxide Anhydrous Catalog Numbers: I116-3, I116-500 Synonyms: Ferric Oxide Red; Iron (III) Oxide; Iron Sesquioxide; Red Iron Oxide. Fisher Scientific Company Identification: One Reagent Lane Fair Lawn, NJ 07410 For information in the US, call: 201-796-7100 Emergency Number US: 201-796-7100 CHEMTREC Phone Number, US: 800-424-9300 Section 2 - Composition, Information on Ingredients ---------------------------------------- CAS#: 1309-37-1 Chemical Name: Iron (III) Oxide %: 100 EINECS#: 215-168-2 ---------------------------------------- Hazard Symbols: None listed Risk Phrases: None listed Section 3 - Hazards Identification EMERGENCY OVERVIEW Warning! May cause respiratory tract irritation. May cause mechanical eye and skin irritation. Inhalation of fumes may cause metal-fume fever. Causes severe digestive tract irritation with pain, nausea, vomiting and diarrhea. May corrode the digestive tract with hemorrhaging and possible shock. Target Organs: None. Potential Health Effects Eye: Dust may cause mechanical irritation. Skin: Dust may cause mechanical irritation. May cause severe and permanent damage to the digestive tract. May cause liver damage. Causes severe pain, Ingestion: nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and shock. May cause hemorrhaging of the digestive tract. The toxicological properties of this substance have not been fully investigated. Dust is irritating to the respiratory tract. Inhalation of fumes may cause metal fume fever, which is characterized Inhalation: by flu-like symptoms with metallic taste, fever, chills, cough, weakness, chest pain, muscle pain and increased white blood cell count. Chronic: Chronic inhalation may cause effects similar to those of acute inhalation. -

Labeling Mesenchymal Cells with DMSA-Coated Gold

Silva et al. J Nanobiotechnol (2016) 14:59 DOI 10.1186/s12951-016-0213-x Journal of Nanobiotechnology RESEARCH Open Access Labeling mesenchymal cells with DMSA‑coated gold and iron oxide nanoparticles: assessment of biocompatibility and potential applications Luisa H. A. Silva1, Jaqueline R. da Silva1, Guilherme A. Ferreira2, Renata C. Silva3, Emilia C. D. Lima2, Ricardo B. Azevedo1 and Daniela M. Oliveira1* Abstract Background: Nanoparticles’ unique features have been highly explored in cellular therapies. However, nanoparti- cles can be cytotoxic. The cytotoxicity can be overcome by coating the nanoparticles with an appropriated surface modification. Nanoparticle coating influences biocompatibility between nanoparticles and cells and may affect some cell properties. Here, we evaluated the biocompatibility of gold and maghemite nanoparticles functionalized with 2,3-dimercaptosuccinic acid (DMSA), Au-DMSA and γ-Fe2O3-DMSA respectively, with human mesenchymal stem cells. Also, we tested these nanoparticles as tracers for mesenchymal stem cells in vivo tracking by computed tomography and as agents for mesenchymal stem cells magnetic targeting. Results: Significant cell death was not observed in MTT, Trypan Blue and light microscopy analyses. However, ultra- structural alterations as swollen and degenerated mitochondria, high amounts of myelin figures and structures similar to apoptotic bodies were detected in some mesenchymal stem cells. Au-DMSA and γ-Fe2O3-DMSA labeling did not affect mesenchymal stem cells adipogenesis and osteogenesis differentiation, proliferation rates or lymphocyte suppression capability. The uptake measurements indicated that both inorganic nanoparticles were well uptaken by mesenchymal stem cells. However, Au-DMSA could not be detected in microtomograph after being incorporated by mesenchymal stem cells. -

Titanium Dioxide Nanoparticles: Prospects and Applications in Medicine

nanomaterials Review Titanium Dioxide Nanoparticles: Prospects and Applications in Medicine Daniel Ziental 1 , Beata Czarczynska-Goslinska 2, Dariusz T. Mlynarczyk 3 , Arleta Glowacka-Sobotta 4, Beata Stanisz 5, Tomasz Goslinski 3,* and Lukasz Sobotta 1,* 1 Department of Inorganic and Analytical Chemistry, Poznan University of Medical Sciences, Grunwaldzka 6, 60-780 Poznan, Poland; [email protected] 2 Department of Pharmaceutical Technology, Poznan University of Medical Sciences, Grunwaldzka 6, 60-780 Poznan, Poland; [email protected] 3 Department of Chemical Technology of Drugs, Poznan University of Medical Sciences, Grunwaldzka 6, 60-780 Poznan, Poland; [email protected] 4 Department and Clinic of Maxillofacial Orthopedics and Orthodontics, Poznan University of Medical Sciences, Bukowska 70, 60-812 Poznan, Poland; [email protected] 5 Department of Pharmaceutical Chemistry, Poznan University of Medical Sciences, Grunwaldzka 6, 60-780 Poznan, Poland; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] (T.G.); [email protected] (L.S.) Received: 4 January 2020; Accepted: 19 February 2020; Published: 23 February 2020 Abstract: Metallic and metal oxide nanoparticles (NPs), including titanium dioxide NPs, among polymeric NPs, liposomes, micelles, quantum dots, dendrimers, or fullerenes, are becoming more and more important due to their potential use in novel medical therapies. Titanium dioxide (titanium(IV) oxide, titania, TiO2) is an inorganic compound that owes its recent rise in scientific interest to photoactivity. After the illumination in aqueous media with UV light, TiO2 produces an array of reactive oxygen species (ROS). The capability to produce ROS and thus induce cell death has found application in the photodynamic therapy (PDT) for the treatment of a wide range of maladies, from psoriasis to cancer. -

Depositional Setting of Algoma-Type Banded Iron Formation Blandine Gourcerol, P Thurston, D Kontak, O Côté-Mantha, J Biczok

Depositional Setting of Algoma-type Banded Iron Formation Blandine Gourcerol, P Thurston, D Kontak, O Côté-Mantha, J Biczok To cite this version: Blandine Gourcerol, P Thurston, D Kontak, O Côté-Mantha, J Biczok. Depositional Setting of Algoma-type Banded Iron Formation. Precambrian Research, Elsevier, 2016. hal-02283951 HAL Id: hal-02283951 https://hal-brgm.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02283951 Submitted on 11 Sep 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Accepted Manuscript Depositional Setting of Algoma-type Banded Iron Formation B. Gourcerol, P.C. Thurston, D.J. Kontak, O. Côté-Mantha, J. Biczok PII: S0301-9268(16)30108-5 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.precamres.2016.04.019 Reference: PRECAM 4501 To appear in: Precambrian Research Received Date: 26 September 2015 Revised Date: 21 January 2016 Accepted Date: 30 April 2016 Please cite this article as: B. Gourcerol, P.C. Thurston, D.J. Kontak, O. Côté-Mantha, J. Biczok, Depositional Setting of Algoma-type Banded Iron Formation, Precambrian Research (2016), doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.precamres. 2016.04.019 This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. -

Synthesis and Environmental Chemistry of Silver and Iron Oxide Nanoparticles

SYNTHESIS AND ENVIRONMENTAL CHEMISTRY OF SILVER AND IRON OXIDE NANOPARTICLES By SUSAN ALISON CUMBERLAND A thesis submitted to The University of Birmingham For the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY School of Earth and Environmental Sciences College of Life and Environmental Sciences The University of Birmingham March 2010 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. Abstract Engineered nanoparticles are defined as having a dimension that is between one and one hundred nanometres. With toxicology studies reporting various degrees of toxicity the need to investigate nanoparticle fate and behaviour is vital. Monodispersed engineered nanoparticles were synthesised in-house to produce suitable materials to examine such processes. Iron oxide nanoparticles (5 nm) and citrate coated silver nanoparticles (20 nm) were subjected to different conditions of pH, ionic strength and different types of commercially available natural organic matter. Changes in particle size and aggregation were examined using a multi-method approach. Results showed that the natural organic matter was able to adsorb onto nanoparticle surfaces and improve their stability when subjected to changes in pH and ionic strength, where they would normally aggregate. -

Earth Systems Science Grades 9-12

Earth Systems Science Grades 9-12 Lesson 2: The Irony of Rust The Earth can be considered a family of four major components; a biosphere, atmosphere, hydrosphere, and geosphere. Together, these interacting and all-encompassing subdivisions constitute the structure and dynamics of the entire Earth. These systems do not, and can not, stand alone. This Module demonstrates, at every grade level, the concept that one system depends on every other for molding the Earth into the world we know. For example, the biosphere could not effi ciently prosper as is without gas exchange from the atmosphere, liquid water from the hydrosphere, and food and other materials provided by the geosphere. Similarly, the other systems are signifi cantly affected by the biosphere in one way or another. This Module uses Earth’s systems to provide the ultimate lesson in teamwork. March 2006 2 JOURNEY THROUGH THE UNIVERSE Lesson 2: The Irony of Rust Lesson at a Glance Lesson Overview In this lesson, students will investigate the chemistry of rust—the forma- tion of iron oxide (Fe2O3)—within a modern context, by experimenting with the conditions under which iron oxide forms. Students will apply what they have learned to deduce the atmospheric chemistry at the time that the sediments, which eventually became common iron ore found in the United States and elsewhere, were deposited. Students will interpret the necessary formation conditions of this iron-bearing rock in the context of Earth’s geochemical history and the history of life on Earth. Lesson Duration Four 45-minute class periods plus 10 minutes a day for maintence and observation for two weeks Core Education Standards National Science Education Standards Standard B3: A large number of important reactions involve the transfer of either electrons (oxidation/reduction reactions) or hydrogen ions (acid/base reactions) between reacting ions, molecules, or atoms. -

Superparamagnetic Iron Oxide Nanoparticle Probes for Molecular Imaging

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Departmental Papers (BE) Department of Bioengineering 1-1-2006 Superparamagnetic Iron Oxide Nanoparticle Probes for Molecular Imaging Daniel L. J Thorek University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Antony K. Chen University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Julie Czupryna University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Andrew Tsourkas University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/be_papers Part of the Molecular, Cellular, and Tissue Engineering Commons Recommended Citation Thorek, D. L., Chen, A. K., Czupryna, J., & Tsourkas, A. (2006). Superparamagnetic Iron Oxide Nanoparticle Probes for Molecular Imaging. Retrieved from https://repository.upenn.edu/be_papers/77 Postprint version. Published in Annals of Biomedical Engineering, Volume 34, Issue 1, January 2006, pages 23-38. Publisher URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10439-005-9002-7 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/be_papers/77 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Superparamagnetic Iron Oxide Nanoparticle Probes for Molecular Imaging Abstract The field of molecular imaging has ecentlyr seen rapid advances in the development of novel contrast agents and the implementation of insightful approaches to monitor biological processes non-invasively. In particular, superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles (SPIO) have demonstrated their utility as an important tool for enhancing magnetic resonance contrast, allowing -

Banded Iron Formations

Banded Iron Formations Cover Slide 1 What are Banded Iron Formations (BIFs)? • Large sedimentary structures Kalmina gorge banded iron (Gypsy Denise 2013, Creative Commons) BIFs were deposited in shallow marine troughs or basins. Deposits are tens of km long, several km wide and 150 – 600 m thick. Photo is of Kalmina gorge in the Pilbara (Karijini National Park, Hamersley Ranges) 2 What are Banded Iron Formations (BIFs)? • Large sedimentary structures • Bands of iron rich and iron poor rock Iron rich bands: hematite (Fe2O3), magnetite (Fe3O4), siderite (FeCO3) or pyrite (FeS2). Iron poor bands: chert (fine‐grained quartz) and low iron oxide levels Rock sample from a BIF (Woudloper 2009, Creative Commons 1.0) Iron rich bands are composed of hematitie (Fe2O3), magnetite (Fe3O4), siderite (FeCO3) or pyrite (FeS2). The iron poor bands contain chert (fine‐grained quartz) with lesser amounts of iron oxide. 3 What are Banded Iron Formations (BIFs)? • Large sedimentary structures • Bands of iron rich and iron poor rock • Archaean and Proterozoic in age BIF formation through time (KG Budge 2020, public domain) BIFs were deposited for 2 billion years during the Archaean and Proterozoic. There was another short time of deposition during a Snowball Earth event. 4 Why are BIFs important? • Iron ore exports are Australia’s top earner, worth $61 billion in 2017‐2018 • Iron ore comes from enriched BIF deposits Rio Tinto iron ore shiploader in the Pilbara (C Hargrave, CSIRO Science Image) Australia is consistently the leading iron ore exporter in the world. We have large deposits where the iron‐poor chert bands have been leached away, leaving 40%‐60% iron. -

Chemo-Electrical Gas Sensors Based on Conducting Polymer Hybrids

polymers Review Chemo-Electrical Gas Sensors Based on Conducting Polymer Hybrids Seon Joo Park 1, Chul Soon Park 1,2 and Hyeonseok Yoon 2,3,* 1 Hazards Monitoring Bionano Research Center, Korea Research Institute of Bioscience and Biotechnology (KRIBB), 125 Gwahak-ro, Yuseong-gu, 34141 Daejeon, Korea; [email protected] (S.J.P.); [email protected] (C.S.P.) 2 Department of Polymer Engineering, Graduate School, Chonnam National University, 77 Yongbong-ro, Buk-gu, 61186 Gwangju, Korea 3 School of Polymer Science and Engineering, Chonnam National University, 77 Yongbong-ro, Buk-gu, 61186 Gwangju, Korea * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +82-62-530-1778 Academic Editor: Po-Chih Yang Received: 10 March 2017; Accepted: 24 April 2017; Published: 26 April 2017 Abstract: Conducting polymer (CP) hybrids, which combine CPs with heterogeneous species, have shown strong potential as electrical transducers in chemosensors. The charge transport properties of CPs are based on chemical redox reactions and provide various chemo-electrical signal transduction mechanisms. Combining CPs with other functional materials has provided opportunities to tailor their major morphological and physicochemical properties, often resulting in enhanced sensing performance. The hybrids can provide an enlarged effective surface area for enhanced interaction and chemical specificity to target analytes via a new signal transduction mechanism. Here, we review a selection of important CPs, including polyaniline, polypyrrole, polythiophene and their derivatives, to fabricate versatile organic and inorganic hybrid materials and their chemo-electrical sensing performance. We focus on what benefits can be achieved through material hybridization in the sensing application. Moreover, state-of-the-art trends in technologies of CP hybrid sensors are discussed, as are limitations and challenges. -

Combustion of Iron Wool – Student Sheet

Combustion of iron wool – Student sheet To study Iron is a metal. Iron wool is made up of thin strands of iron loosely bundled together. Your teacher has attached a piece of iron wool to a see-saw balance. At the other end of the see-saw is a piece of Plasticine. Iron wool can combust. Your teacher is going to make the iron wool combust by heating it. If there is a change in mass, the see-saw will either tip to the left or to the right. To discuss or to answer 1 What do you think will happen? ............................................................................................................................................................. 2 Why do you think this will happen? ............................................................................................................................................................. ............................................................................................................................................................. 3 What do you see happen when it is demonstrated? ............................................................................................................................................................. 4 Was your prediction correct? ............................................................................................................................................................. Nuffield Practical Work for Learning: Model-based Inquiry • Combustion of iron wool • Student sheets page 1 of 4 © Nuffield Foundation 2013 • downloaded from -

Nanocomposite Membranes for Liquid and Gas Separations from the Perspective of Nanostructure Dimensions

membranes Review Nanocomposite Membranes for Liquid and Gas Separations from the Perspective of Nanostructure Dimensions Pei Sean Goh *, Kar Chun Wong and Ahmad Fauzi Ismail Advanced Membrane Technology Research Centre (AMTEC), School of Chemical and Energy Engineering, Faculty of Engineering, Universiti Teknologi Malaysia, Johor Bahru 81310, Malaysia; [email protected] (K.C.W.); [email protected] (A.F.I.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +60-7-553-5812 Received: 26 September 2020; Accepted: 19 October 2020; Published: 21 October 2020 Abstract: One of the critical aspects in the design of nanocomposite membrane is the selection of a well-matched pair of nanomaterials and a polymer matrix that suits their intended application. By making use of the fascinating flexibility of nanoscale materials, the functionalities of the resultant nanocomposite membranes can be tailored. The unique features demonstrated by nanomaterials are closely related to their dimensions, hence a greater attention is deserved for this critical aspect. Recognizing the impressive research efforts devoted to fine-tuning the nanocomposite membranes for a broad range of applications including gas and liquid separation, this review intends to discuss the selection criteria of nanostructured materials from the perspective of their dimensions for the production of high-performing nanocomposite membranes. Based on their dimension classifications, an overview of the characteristics of nanomaterials used for the development of nanocomposite membranes is presented. The advantages and roles of these nanomaterials in advancing the performance of the resultant nanocomposite membranes for gas and liquid separation are reviewed. By highlighting the importance of dimensions of nanomaterials that account for their intriguing structural and physical properties, the potential of these nanomaterials in the development of nanocomposite membranes can be fully harnessed. -

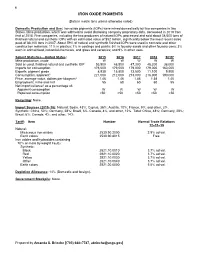

Iron Oxide Pigments Data Sheet

90 IRON OXIDE PIGMENTS (Data in metric tons unless otherwise noted) Domestic Production and Use: Iron oxide pigments (IOPs) were mined domestically by two companies in two States. Mine production, which was withheld to avoid disclosing company proprietary data, decreased in 2019 from that of 2018. Five companies, including the two producers of natural IOPs, processed and sold about 38,000 tons of finished natural and synthetic IOPs with an estimated value of $52 million, significantly below the most recent sales peak of 88,100 tons in 2007. About 59% of natural and synthetic finished IOPs were used in concrete and other construction materials; 11% in plastics; 7% in coatings and paints; 5% in foundry sands and other foundry uses; 3% each in animal food, industrial chemicals, and glass and ceramics; and 9% in other uses. Salient Statistics—United States: 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019e Mine production, crude W W W W W Sold or used, finished natural and synthetic IOP 53,500 48,500 47,300 48,200 38,000 Imports for consumption 176,000 179,000 179,000 179,000 160,000 Exports, pigment grade 8,930 15,800 13,500 11,100 9,900 Consumption, apparent1 221,000 212,000 213,000 216,000 190,000 Price, average value, dollars per kilogram2 1.46 1.46 1.46 1.58 1.40 Employment, mine and mill 55 60 60 60 55 Net import reliance3 as a percentage of: Apparent consumption W W W W W Reported consumption >50 >50 >50 >50 >50 Recycling: None. Import Sources (2015–18): Natural: Spain, 43%; Cyprus, 36%; Austria, 10%; France, 9%; and other, 2%.