Earth Systems Science Grades 9-12

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Iron (III) Oxide Anhydrous

Material Safety Data Sheet Iron (III) Oxide Anhydrous MSDS# 11521 Section 1 - Chemical Product and Company Identification MSDS Name: Iron (III) Oxide Anhydrous Catalog Numbers: I116-3, I116-500 Synonyms: Ferric Oxide Red; Iron (III) Oxide; Iron Sesquioxide; Red Iron Oxide. Fisher Scientific Company Identification: One Reagent Lane Fair Lawn, NJ 07410 For information in the US, call: 201-796-7100 Emergency Number US: 201-796-7100 CHEMTREC Phone Number, US: 800-424-9300 Section 2 - Composition, Information on Ingredients ---------------------------------------- CAS#: 1309-37-1 Chemical Name: Iron (III) Oxide %: 100 EINECS#: 215-168-2 ---------------------------------------- Hazard Symbols: None listed Risk Phrases: None listed Section 3 - Hazards Identification EMERGENCY OVERVIEW Warning! May cause respiratory tract irritation. May cause mechanical eye and skin irritation. Inhalation of fumes may cause metal-fume fever. Causes severe digestive tract irritation with pain, nausea, vomiting and diarrhea. May corrode the digestive tract with hemorrhaging and possible shock. Target Organs: None. Potential Health Effects Eye: Dust may cause mechanical irritation. Skin: Dust may cause mechanical irritation. May cause severe and permanent damage to the digestive tract. May cause liver damage. Causes severe pain, Ingestion: nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and shock. May cause hemorrhaging of the digestive tract. The toxicological properties of this substance have not been fully investigated. Dust is irritating to the respiratory tract. Inhalation of fumes may cause metal fume fever, which is characterized Inhalation: by flu-like symptoms with metallic taste, fever, chills, cough, weakness, chest pain, muscle pain and increased white blood cell count. Chronic: Chronic inhalation may cause effects similar to those of acute inhalation. -

Depositional Setting of Algoma-Type Banded Iron Formation Blandine Gourcerol, P Thurston, D Kontak, O Côté-Mantha, J Biczok

Depositional Setting of Algoma-type Banded Iron Formation Blandine Gourcerol, P Thurston, D Kontak, O Côté-Mantha, J Biczok To cite this version: Blandine Gourcerol, P Thurston, D Kontak, O Côté-Mantha, J Biczok. Depositional Setting of Algoma-type Banded Iron Formation. Precambrian Research, Elsevier, 2016. hal-02283951 HAL Id: hal-02283951 https://hal-brgm.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02283951 Submitted on 11 Sep 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Accepted Manuscript Depositional Setting of Algoma-type Banded Iron Formation B. Gourcerol, P.C. Thurston, D.J. Kontak, O. Côté-Mantha, J. Biczok PII: S0301-9268(16)30108-5 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.precamres.2016.04.019 Reference: PRECAM 4501 To appear in: Precambrian Research Received Date: 26 September 2015 Revised Date: 21 January 2016 Accepted Date: 30 April 2016 Please cite this article as: B. Gourcerol, P.C. Thurston, D.J. Kontak, O. Côté-Mantha, J. Biczok, Depositional Setting of Algoma-type Banded Iron Formation, Precambrian Research (2016), doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.precamres. 2016.04.019 This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. -

Banded Iron Formations

Banded Iron Formations Cover Slide 1 What are Banded Iron Formations (BIFs)? • Large sedimentary structures Kalmina gorge banded iron (Gypsy Denise 2013, Creative Commons) BIFs were deposited in shallow marine troughs or basins. Deposits are tens of km long, several km wide and 150 – 600 m thick. Photo is of Kalmina gorge in the Pilbara (Karijini National Park, Hamersley Ranges) 2 What are Banded Iron Formations (BIFs)? • Large sedimentary structures • Bands of iron rich and iron poor rock Iron rich bands: hematite (Fe2O3), magnetite (Fe3O4), siderite (FeCO3) or pyrite (FeS2). Iron poor bands: chert (fine‐grained quartz) and low iron oxide levels Rock sample from a BIF (Woudloper 2009, Creative Commons 1.0) Iron rich bands are composed of hematitie (Fe2O3), magnetite (Fe3O4), siderite (FeCO3) or pyrite (FeS2). The iron poor bands contain chert (fine‐grained quartz) with lesser amounts of iron oxide. 3 What are Banded Iron Formations (BIFs)? • Large sedimentary structures • Bands of iron rich and iron poor rock • Archaean and Proterozoic in age BIF formation through time (KG Budge 2020, public domain) BIFs were deposited for 2 billion years during the Archaean and Proterozoic. There was another short time of deposition during a Snowball Earth event. 4 Why are BIFs important? • Iron ore exports are Australia’s top earner, worth $61 billion in 2017‐2018 • Iron ore comes from enriched BIF deposits Rio Tinto iron ore shiploader in the Pilbara (C Hargrave, CSIRO Science Image) Australia is consistently the leading iron ore exporter in the world. We have large deposits where the iron‐poor chert bands have been leached away, leaving 40%‐60% iron. -

Combustion of Iron Wool – Student Sheet

Combustion of iron wool – Student sheet To study Iron is a metal. Iron wool is made up of thin strands of iron loosely bundled together. Your teacher has attached a piece of iron wool to a see-saw balance. At the other end of the see-saw is a piece of Plasticine. Iron wool can combust. Your teacher is going to make the iron wool combust by heating it. If there is a change in mass, the see-saw will either tip to the left or to the right. To discuss or to answer 1 What do you think will happen? ............................................................................................................................................................. 2 Why do you think this will happen? ............................................................................................................................................................. ............................................................................................................................................................. 3 What do you see happen when it is demonstrated? ............................................................................................................................................................. 4 Was your prediction correct? ............................................................................................................................................................. Nuffield Practical Work for Learning: Model-based Inquiry • Combustion of iron wool • Student sheets page 1 of 4 © Nuffield Foundation 2013 • downloaded from -

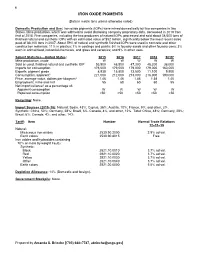

Iron Oxide Pigments Data Sheet

90 IRON OXIDE PIGMENTS (Data in metric tons unless otherwise noted) Domestic Production and Use: Iron oxide pigments (IOPs) were mined domestically by two companies in two States. Mine production, which was withheld to avoid disclosing company proprietary data, decreased in 2019 from that of 2018. Five companies, including the two producers of natural IOPs, processed and sold about 38,000 tons of finished natural and synthetic IOPs with an estimated value of $52 million, significantly below the most recent sales peak of 88,100 tons in 2007. About 59% of natural and synthetic finished IOPs were used in concrete and other construction materials; 11% in plastics; 7% in coatings and paints; 5% in foundry sands and other foundry uses; 3% each in animal food, industrial chemicals, and glass and ceramics; and 9% in other uses. Salient Statistics—United States: 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019e Mine production, crude W W W W W Sold or used, finished natural and synthetic IOP 53,500 48,500 47,300 48,200 38,000 Imports for consumption 176,000 179,000 179,000 179,000 160,000 Exports, pigment grade 8,930 15,800 13,500 11,100 9,900 Consumption, apparent1 221,000 212,000 213,000 216,000 190,000 Price, average value, dollars per kilogram2 1.46 1.46 1.46 1.58 1.40 Employment, mine and mill 55 60 60 60 55 Net import reliance3 as a percentage of: Apparent consumption W W W W W Reported consumption >50 >50 >50 >50 >50 Recycling: None. Import Sources (2015–18): Natural: Spain, 43%; Cyprus, 36%; Austria, 10%; France, 9%; and other, 2%. -

05/2203 Iron Oxide Extraction from Lunar and Martian Regoliths

05/2203 Iron oxide extraction from lunar and Martian regoliths Type of activity: Medium Study (4 months, 25 KEUR) Background The Reformer iron Sponge Cycle (RESC) has been proposed as a valid process to produce highly pure hydrogen from virtually any kind of hydrocarbon fuel on a bed of iron oxide (magnetite Fe3O4), present in the soils of the Moon and Mars. The process has been investigated in the frame of the Ariadna Call for Proposals 04/01 in view of future long-term manned lunar and Martian exploration. The process permits to operate a hydrogen-oxygen fuel cell for electrical power generation by producing hydrogen from either high energy density fuels brought from Earth or from fuels produced in situ (e.g. methane from the Sabatier process of from biomass decomposition). Fuels are converted into a mixture of hydrogen and carbon monoxide in a reforming reactor. In the following Iron Sponge Cycle iron oxide (magnetite/wuestite) is initially reduced by hydrogen and carbon monoxide to a lower oxide or down to iron metal with production of water steam and carbon dioxide. In a second step water steam is passed on the formed iron metal bed; iron oxide is replenished and water steam is reduced to highly pure hydrogen which can be fed without further purification treatments to the anodic compartment of a fuel cell for electrical power generation. The contact mass (iron/iron oxide) properties as size, porosity and composition of the pellets are very critical. The use of pure iron would theoretically maximise the efficiency of the cycle; the lifetime of the pellets is however limited by sintering effects. -

Iron Oxide Pigments

IRON OXIDE PIGMENTS By Michael J. Potter Domestic survey data and tables were prepared by Richelle J. Ellis, statistical assistant, and the world production table was prepared by Regina R. Coleman, international data coordinator. Natural iron oxides are derived from hematite, which is a red not included in tables 1, 2, and 4. iron oxide mineral; limonites, which vary from yellow to brown, Bayer Corp. introduced two new yellow grades of synthetic such as ochers, siennas, and umbers; and magnetite, which is IOPs, which were geared toward use in standard solvent-based black iron oxide. Synthetic iron oxide pigments are produced paints and coatings, as well as high solids and water-based from basic chemicals. The three major methods for the paints. One of the pigments was being manufactured at the manufacture of synthetic iron oxides are thermal decomposition company’s new iron oxide unit at New Martinsville, WV, and of iron salts or iron compounds, precipitation of iron salts the other yellow pigment was being made at Bayer’s facility usually accompanied by oxidation, and reduction of organic near Sao Paulo, Brazil, specifically for sale in North American compounds by iron (Podolsky and Keller, 1994, p. 765, 772). markets (Bayer Corp., October 23, 2000, Bayer Corp. introduces two new yellow grades of synthetic iron oxide Production pigments for use in architectural paints and coatings, accessed June 21, 2001, at URL http://www.bayerus.com/new/2000/ U.S. output of finished natural (mined) iron oxide pigments 10.23.00.html). (IOPs) sold by processors in 2000 was 87,800 metric tons (t), Laporte plc announced its intention to sell its pigments and about 5% less than in 1999; this category accounted for 51% of additives companies to K-L Holdings Inc., a company the tonnage and 15% of the value of total IOP output. -

Analyses of High-Iron Sedimentary Bedrock and Diagenetic Features Observed with Chemcam at Vera Rubin Ridge, Gale Crater, Mars: Calibration and Characterization G

Analyses of High-Iron Sedimentary Bedrock and Diagenetic Features Observed With ChemCam at Vera Rubin Ridge, Gale Crater, Mars: Calibration and Characterization G. David, A. Cousin, O. Forni, P.-y. Meslin, E. Dehouck, N. Mangold, J. l’Haridon, W. Rapin, O. Gasnault, J. R. Johnson, et al. To cite this version: G. David, A. Cousin, O. Forni, P.-y. Meslin, E. Dehouck, et al.. Analyses of High-Iron Sedimentary Bedrock and Diagenetic Features Observed With ChemCam at Vera Rubin Ridge, Gale Crater, Mars: Calibration and Characterization. Journal of Geophysical Research. Planets, Wiley-Blackwell, 2020, 125 (10), 10.1029/2019JE006314. hal-03093150 HAL Id: hal-03093150 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-03093150 Submitted on 16 Jan 2021 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. David Gaël (Orcid ID: 0000-0002-2719-1586) Cousin Agnès (Orcid ID: 0000-0001-7823-7794) Forni Olivier (Orcid ID: 0000-0001-6772-9689) Meslin Pierre-Yves (Orcid ID: 0000-0002-0703-3951) Dehouck Erwin (Orcid ID: 0000-0002-1368-4494) Mangold Nicolas (Orcid ID: 0000-0002-0022-0631) Rapin William (Orcid ID: 0000-0003-4660-8006) Gasnault Olivier (Orcid ID: 0000-0002-6979-9012) Johnson Jeffrey, R. -

Physical Properties of Iron Oxide Nanoparticles

The University of Maine DigitalCommons@UMaine Honors College Spring 2015 Physical Properties of Iron Oxide Nanoparticles Nicklaus Carter The University of Maine Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/honors Part of the Biomedical Engineering and Bioengineering Commons Recommended Citation Carter, Nicklaus, "Physical Properties of Iron Oxide Nanoparticles" (2015). Honors College. 210. https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/honors/210 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors College by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PHYSICAL PROPERTIES OF IRON OXIDE NANOPARTICLES By Nicklaus Carter A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for a Degree with Honors (Bioengineering) The Honors College University of Maine May 2015 Advisory Committee: Michael D. Mason, Ph. D, Professor of Bioengineering, Advisor Sara L. Walton, Ph.D, Professor of Bioengineering William J. DeSisto, Ph.D, Professor of Chemical Engineering Robert W. Meulenberg, Ph. D, Associate Professor of Physics and LASST Sarah Harlan-Haughey, Ph. D, Professor of English and Honors ABSTRACT: Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) relies heavily on contrast agents such that diagnosis of various diseases can be made with increased confidence. Current contrast agents for MRI depend on various chelated molecules composed of a toxic gadolinium ion, Gd3+. In 2006, a discovery was made connecting Nephrogenic Systemic Fibrosis (NSF) and these gadolinium based contrast agents (GBCAs). The connection between life threatening NSF and GBCAs stems from patients with pre-existing kidney malfunctions. It has been proposed that an alternative agent such as iron oxide nanoparticles (IONPs) be investigated. -

Extraction of Iron on a Match Head!

Extraction of iron on a match head! 41 Introduction Students reduce iron(III) oxide with carbon on a match head to produce iron in this small scale example of metal extraction. The experiment can be used to highlight aspects of the reactivity series. Lesson organisation This experiment can easily be carried out on an individual basis by students. The experiment itself is very quick to do provided that the apparatus and chemicals are already set out around the laboratory. Apparatus and chemicals Eye protection Each student (or pair of students) will need: • Match (non-safety) (see note 1) Tongs (crucible tongs) Weighing boat (small white plastic ones are ideal) Spatula Students will also need access to: Bunsen burner Heat resistant mat Magnet (e.g. bar magnet) Iron(III) oxide powder (Low hazard) (see note 2) Sodium carbonate powder (Irritant) (see note 2) Water (see note 2) Technical notes Iron(III) oxide powder (Low hazard). Refer to CLEAPSS® Hazcard 55A. Sodium carbonate (Irritant). Refer to CLEAPSS® Hazcard 95A. 1 The experiment works best with non-safety matches. These are often referred to as 'strike anywhere' matches and have a pinkish-red head. 2 Small amounts (a few spatula measures are sufficient) of each of the powders can be provided in, for example, Petri dishes or watch glasses. Groups of students can share the chemicals. The water can be provided in a small beaker. 121 Procedure HEALTH & SAFETY: Wear eye protection • a Dip the head of a match in water to moisten it. b Roll the damp match head first in sodium carbonate powder, then in iron(III) oxide powder. -

Effect of Iron (III) Oxide Powder on Thermal Conductivity and Diffusivity of Lime Mortar

materials Article Effect of Iron (III) Oxide Powder on Thermal Conductivity and Diffusivity of Lime Mortar Francesc Masdeu * , Cristian Carmona, Gabriel Horrach and Joan Muñoz Department of Industrial Engineering and Construction, University of Balearic Islands, Ctra. de Valldemossa km 7.5, E07122 Palma de Mallorca, Spain; [email protected] (C.C.); [email protected] (G.H.); [email protected] (J.M.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +34-971-259790 Abstract: One of the challenges in construction is the improvement of energy efficiency of buildings. Development of construction materials of low thermal conductivity is a straightforward way to improve heat isolating capability of an enclosure. Lime mortar has a number of advantageous and peculiar properties and was widely used until the “irruption” of Portland cement. Currently, lime mortar is still used in restoration of traditional buildings or, according to the urban regulations, in catalogued constructions. The goal of the present study is the improvement of the heat isolating capability of lime mortars. The strategy of this work is the addition of iron (III) oxide powder, which is one of the possible components forming the cements, to a base lime mortar. The reason to choose Fe2O3 was two-fold. The first reason is low thermal conductivity of Fe2O3 compared to lime mortar. The second reason is that the low solubility and small size of iron (III) oxide particles have an effect on the thermal conductivity across the lime particles. The effect of iron (III) oxide powder on the thermal conductivity has been experimentally determined by the hot-box method. -

Are There Abiotically-Precipitated Iron-Formations on Mars?

Mineral Spectroscopy: A Tribute to Roger G. Burns © The Geochemical Society, Special Publication No.5, 1996 Editors: M. D. Dyar, C. McCammon and M. W. Schaefer Are there abiotically-precipitated iron-formations on Mars? M. W. SCHAEFER Yale University, Department of Geology and Geophysics, P. O. Box 208109, New Haven, CT 06520-8109, U.S.A. Abstract- In early times, surface conditions on Mars and Earth were probably quite similar, however, the two planets took different paths in their evolution. Banded iron-formations (BIFs) were prevalent on Earth in the Archean, and the likelihood of their formation on Mars at the same time is investigated. There are several abiotic mechanisms for producing banded iron-formations on Earth. These are: (1) oxidation of ferrous iron by free oxygen, (2) photooxidation of ferrous iron, (3) oxidation of ferrous iron by hydrogen peroxide, and (4) anoxic precipitation of ferrous iron by changes in pH. Any of these mechanisms could have been active on Mars in its distant past, to produce BIFs there as well, which should be observable today. The minerals one would expect to observe on the surface of a BIF on Mars are indeed thought to exist on Mars, but unfortunately BIFs are not unique in containing these minerals, and confirmation of the existence of BIFs on Mars will have to wait for more data. Proof of the existence of BIFs on Mars would give us valuable information about the early history of the planet Mars as well as Earth. It would act to confirm models of Mars that include a warm, wet period, and the existence of bodies of standing water.