23.1 Conflict &/Or Concord

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gavin Ames Avid Editor

Gavin Ames Avid Editor Profile Gavin is an exceptionally talented editor. Fast, creative, and very technically minded. He is one of the best music editors around, with vast live multi-cam experience ranging from The Isle of Wight Festival, to Take That, Faithless and Primal Scream concerts. Since excelling in the music genre, Gavin went on to develop his skills in comedy, editing Shooting Stars. His talents have since gone from strength to strength and he now has a wide range of high-end credits under his belt, such as live stand up for Bill Bailey, Steven Merchant, Ed Byrne and Angelos Epithemiou. He has also edited sketch comedy, a number of studio shows and comedy docs. Gavin has a real passion for editing comedy and clients love working with him so much that they ask him back time and time again! Comedy / Entertainment / Factual “The World According to Jeff Goldblum” Series 2. Through the prism of Jeff Goldblum's always inquisitive and highly entertaining mind, nothing is as it seem. Each episode is centred around something we all love — like sneakers or ice cream — as Jeff pulls the thread on these deceptively familiar objects and unravels a wonderful world of astonishing connections, fascinating science and history, amazing people, and a whole lot of surprising big ideas and insights. Nutopia for National Geographic and Disney + “Guessable” In this comedy game show, two celebrity teams compete to identify the famous name or object inside a mystery box. Sara Pascoe hosts the show with John Kearns on hand as her assistant. Alan Davies and Darren Harriott are the team captains, in a format that puts a twist on classic family games. -

Jewish Issue in Friedrich Gorenstein's Writing

JEWISH ISSUE IN FRIEDRICH GORENSTEIN’S WRITING Elina Vasiljeva, Dr. philol. Daugavpils University/Institute of Comparative Studies , Latvia Abstract: The paper discusses the specific features in the depiction of the Jewish issue in the writings by Friedrich Gorenstein.The nationality of Gorenstein is not hard to define, while his writing is much more ambiguous to classify in any national tradition. The Jewish theme is undoubtedly the leading one in his writing. Jewish issue is a part of discussions about private fates, the history of Russia, the Biblical sense of the existence of the whole humankind. Jewish subject matter as such appears in all of his works and these are different parts of a single system. Certainly, Jewish issues partially differ in various literary works by Gorenstein but implicitly they are present in all texts and it is not his own intentional wish to emphasize the Jewish issue: Jewish world is a part of the universe, it is not just the tragic fate of a people but a test of humankind for humanism, for the possibility to become worthy of the supreme redemption. The Jewish world of Gorenstein is a mosaic world in essence. The sign of exile and dispersal is never lifted. Key Words: Jewish , Biblical, anti-Semitism Introduction The phenomenon of the reception of one culture in the framework of other cultures has been known since the antiquity. Since the ancient times, intercultural dialogue has been implemented exactly in this form. And this reception of another culture does not claim to be objective. On the contrary, it reflects not the peculiarities of the culture perceived, but rather the particularities of artistic consciousness of the perceiving culture. -

Poetry Sampler

POETRY SAMPLER 2020 www.academicstudiespress.com CONTENTS Voices of Jewish-Russian Literature: An Anthology Edited by Maxim D. Shrayer New York Elegies: Ukrainian Poems on the City Edited by Ostap Kin Words for War: New Poems from Ukraine Edited by Oksana Maksymchuk & Max Rosochinsky The White Chalk of Days: The Contemporary Ukrainian Literature Series Anthology Compiled and edited by Mark Andryczyk www.academicstudiespress.com Voices of Jewish-Russian Literature An Anthology Edited, with Introductory Essays by Maxim D. Shrayer Table of Contents Acknowledgments xiv Note on Transliteration, Spelling of Names, and Dates xvi Note on How to Use This Anthology xviii General Introduction: The Legacy of Jewish-Russian Literature Maxim D. Shrayer xxi Early Voices: 1800s–1850s 1 Editor’s Introduction 1 Leyba Nevakhovich (1776–1831) 3 From Lament of the Daughter of Judah (1803) 5 Leon Mandelstam (1819–1889) 11 “The People” (1840) 13 Ruvim Kulisher (1828–1896) 16 From An Answer to the Slav (1849; pub. 1911) 18 Osip Rabinovich (1817–1869) 24 From The Penal Recruit (1859) 26 Seething Times: 1860s–1880s 37 Editor’s Introduction 37 Lev Levanda (1835–1888) 39 From Seething Times (1860s; pub. 1871–73) 42 Grigory Bogrov (1825–1885) 57 “Childhood Sufferings” from Notes of a Jew (1863; pub. 1871–73) 59 vi Table of Contents Rashel Khin (1861–1928) 70 From The Misfit (1881) 72 Semyon Nadson (1862–1887) 77 From “The Woman” (1883) 79 “I grew up shunning you, O most degraded nation . .” (1885) 80 On the Eve: 1890s–1910s 81 Editor’s Introduction 81 Ben-Ami (1854–1932) 84 Preface to Collected Stories and Sketches (1898) 86 David Aizman (1869–1922) 90 “The Countrymen” (1902) 92 Semyon Yushkevich (1868–1927) 113 From The Jews (1903) 115 Vladimir Jabotinsky (1880–1940) 124 “In Memory of Herzl” (1904) 126 Sasha Cherny (1880–1932) 130 “The Jewish Question” (1909) 132 “Judeophobes” (1909) 133 S. -

{PDF EPUB} the Poetry of Richard Milhous Nixon by Richard M. Nixon Four Poems by Richard Milhous Nixon

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} The Poetry of Richard Milhous Nixon by Richard M. Nixon Four Poems by Richard Milhous Nixon. Abraham Lincoln, John Quincy Adams, and Jimmy Carter all published collections of poetry—and I don’t mean to diminish their stately, often tender contributions to arts and letters by what follows. But the simple fact of the matter is, their poetical efforts pale in comparison to Richard Nixon, who was, and remains, the most essential poet-president the United States of America has ever produced. The Poetry of Richard Milhous Nixon , a slim volume compiled by Jack S. Margolis and published in 1974, stands as a seminal work in verse. Comprising direct excerpts from the Watergate tapes—arguably the most fecund stage of Nixon’s career—it fuses the rugged rhetoric of statesmanship to the lithe contours of song, all rendered in assured, supple, poignant free verse. Below, to celebrate Presidents’ Day, are four selections from this historic chapbook, which has, lamentably, slipped out of print. THE POSITION The position is To withhold Information And to cover up This is Totally true. You could say This is Totally untrue. TOGETHER We are all In it Together. We take A few shots And It will be over. Don’t worry. I wouldn’t Want to be On the other side Right now. IN THE END In the end We are going To be bled To death. And in the end, It is all going To come out anyway. Then you get the worst Of both worlds. The power of Nixon’s poems was duly recognized by his peers—other writers, most notably Thomas Pynchon, have used them as epigraphs. -

1953 New Year Honours 1953 New Year Honours

12/19/2018 1953 New Year Honours 1953 New Year Honours The New Year Honours 1953 for the United Kingdom were announced on 30 December 1952,[1] to celebrate the year passed and mark the beginning of 1953. This was the first New Year Honours since the accession of Queen Elizabeth II. The Honours list is a list of people who have been awarded one of the various orders, decorations, and medals of the United Kingdom. Honours are split into classes ("orders") and are graded to distinguish different degrees of achievement or service, most medals are not graded. The awards are presented to the recipient in one of several investiture ceremonies at Buckingham Palace throughout the year by the Sovereign or her designated representative. The orders, medals and decorations are awarded by various honours committees which meet to discuss candidates identified by public or private bodies, by government departments or who are nominated by members of the public.[2] Depending on their roles, those people selected by committee are submitted to Ministers for their approval before being sent to the Sovereign for final The insignia of the Grand Cross of the approval. As the "fount of honour" the monarch remains the final arbiter for awards.[3] In the case Order of St Michael and St George of certain orders such as the Order of the Garter and the Royal Victorian Order they remain at the personal discretion of the Queen.[4] The recipients of honours are displayed here as they were styled before their new honour, and arranged by honour, with classes (Knight, Knight Grand Cross, etc.) and then divisions (Military, Civil, etc.) as appropriate. -

Illinois Current Through P.A

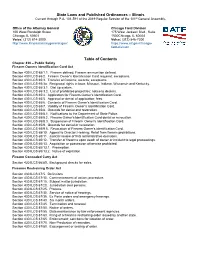

State Laws and Published Ordinances – Illinois Current through P.A. 101-591 of the 2019 Regular Session of the 101st General Assembly. Office of the Attorney General Chicago Field Division 100 West Randolph Street 175 West Jackson Blvd., Suite Chicago, IL 60601 1500Chicago, IL 60604 Voice: (312) 814-3000 Voice: (312) 846-7200 http://www.illinoisattorneygeneral.gov/ https://www.atf.gov/chicago- field-division Table of Contents Chapter 430 – Public Safety Firearm Owners Identification Card Act Section 430 ILCS 65/1.1. Firearm defined; Firearm ammunition defined. Section 430 ILCS 65/2. Firearm Owner's Identification Card required; exceptions. Section 430 ILCS 65/3. Transfer of firearms; records; exceptions. Section 430 ILCS 65/3a. Reciprocal rights in Iowa, Missouri, Indiana, Wisconsin and Kentucky. Section 430 ILCS 65/3.1. Dial up system. Section 430 ILCS 65/3.2. List of prohibited projectiles; notice to dealers. Section 430 ILCS 65/4. Application for Firearm Owner's Identification Card. Section 430 ILCS 65/5. Approval or denial of application; fees. Section 430 ILCS 65/6. Contents of Firearm Owner's Identification Card. Section 430 ILCS 65/7. Validity of Firearm Owner’s Identification Card. Section 430 ILCS 65/8. Grounds for denial and revocation. Section 430 ILCS 65/8.1. Notifications to the Department of State Police. Section 430 ILCS 65/8.2. Firearm Owner's Identification Card denial or revocation. Section 430 ILCS 65/8.3. Suspension of Firearm Owner's Identification Card. Section 430 ILCS 65/9. Grounds for denial or revocation. Section 430 ILCS 65/9.5. Revocation of Firearm Owner's Identification Card. -

7.62×51Mm NATO 1 7.62×51Mm NATO

7.62×51mm NATO 1 7.62×51mm NATO 7.62×51mm NATO 7.62×51mm NATO rounds compared to AA (LR6) battery. Type Rifle Place of origin United States Service history In service 1954–present Used by United States, NATO, others. Wars Vietnam War, Falklands Conflict, The Troubles, Gulf War, War in Afghanistan, Iraq War, Libyan civil war, among other conflicts Specifications Parent case .308 Winchester (derived from the .300 Savage) Case type Rimless, Bottleneck Bullet diameter 7.82 mm (0.308 in) Neck diameter 8.77 mm (0.345 in) Shoulder diameter 11.53 mm (0.454 in) Base diameter 11.94 mm (0.470 in) Rim diameter 12.01 mm (0.473 in) Rim thickness 1.27 mm (0.050 in) Case length 51.18 mm (2.015 in) Overall length 69.85 mm (2.750 in) Rifling twist 1:12" Primer type Large Rifle Maximum pressure 415 MPa (60,200 psi) Ballistic performance Bullet weight/type Velocity Energy 9.53 g (147 gr) M80 FMJ 833.0 m/s (2,733 ft/s) 3,304 J (2,437 ft·lbf) 11.34 g (175 gr) M118 Long 786.4 m/s (2,580 ft/s) 3,506 J (2,586 ft·lbf) Range BTHP Test barrel length: 24" [1] [2] Source(s): M80: Slickguns, M118 Long Range: US Armorment 7.62×51mm NATO 2 The 7.62×51mm NATO (official NATO nomenclature 7.62 NATO) is a rifle cartridge developed in the 1950s as a standard for small arms among NATO countries. It should not to be confused with the similarly named Russian 7.62×54mmR cartridge. -

PREAMBLE Whereas the People of the State of Oregon Find That Gun Violence in Oregon and the United States, Resulting in Horrific

PREAMBLE Whereas the People of the State of Oregon find that gun violence in Oregon and the United States, resulting in horrific deaths and devastating injuries due to mass shootings and other homicides, is unacceptable at any level; and Whereas the firearms referred to as “semiautomatic assault firearms” are designed with features to allow rapid spray firing or the quick and efficient killing of humans, and the unregulated availability of semiautomatic assault firearms used in such mass shootings and other homicides in Oregon, and throughout the United States, poses a grave and immediate risk to the health, safety and well-being of the citizens of this State, and in particular our children; and Whereas firearms have evolved from muskets to semiautomatic assault firearms, including rifles, shotguns and pistols with enhanced features and with the ability to kill so many in such an increasingly short period of time, unleashing death and unspeakable pain in places that should be safe: our homes, schools, places of worship, shopping malls, communities; and Whereas a failure to resolve long unrest and inequitable treatment of individuals based on race, gender, religion and other distinguishing characteristics and failure to develop legislative tools to remove the ability of those with criminal intent or predisposition to commit violence from acquiring such instruments of carnage and never-ending sadness; It is therefore morally incumbent upon the citizens of Oregon to take immediate action, which we do by this initiative, to reduce the availability of these assault firearms, and thus reduce their ability to cause death and loss in places that should remain safe; Now, therefore, BE IT ENACTED BY THE PEOPLE OF THE STATE OF OREGON: SECTION 1. -

Mg 34 and Mg 42 Machine Guns

MG 34 AND MG 42 MACHINE GUNS CHRIS MC NAB © Osprey Publishing • www.ospreypublishing.com MG 34 AND MG 42 MACHINE GUNS CHRIS McNAB Series Editor Martin Pegler © Osprey Publishing • www.ospreypublishing.com CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 4 DEVELOPMENT 8 The ‘universal’ machine gun USE 27 Flexible firepower IMPACT 62 ‘Hitler’s buzzsaw’ CONCLUSION 74 GLOSSARY 77 BIBLIOGRAPHY & FURTHER READING 78 INDEX 80 © Osprey Publishing • www.ospreypublishing.com INTRODUCTION Although in war all enemy weapons are potential sources of fear, some seem to have a deeper grip on the imagination than others. The AK-47, for example, is actually no more lethal than most other small arms in its class, but popular notoriety and Hollywood representations tend to credit it with superior power and lethality. Similarly, the bayonet actually killed relatively few men in World War I, but the sheer thought of an enraged foe bearing down on you with more than 30cm of sharpened steel was the stuff of nightmares to both sides. In some cases, however, fear has been perfectly justified. During both world wars, for example, artillery caused between 59 and 80 per cent of all casualties (depending on your source), and hence took a justifiable top slot in surveys of most feared tools of violence. The subjects of this book – the MG 34 and MG 42, plus derivatives – are interesting case studies within the scale of soldiers’ fears. Regarding the latter weapon, a US wartime information movie once declared that the gun’s ‘bark was worse than its bite’, no doubt a well-intentioned comment intended to reduce mounting concern among US troops about the firepower of this astonishing gun. -

Critical Company Chronicle Heckler & Koch

Critical Company Chronicle Heckler & Koch How H&K and the German government are jointly responsible for the death and traumatisation of millions of people across the world due to their unrestrained export of small arms to human rights violating and warring states <<Standard version>> Written by Jürgen Grässlin Translated by Ruth Rohde For the GLOBAL NET - STOP THE ARMS TRADE Version: March 2020 Artwork by Jonas Fehlinger, graphic designer and artist, for the GN-STAT Contents 1.1 What the Official Histories of H&K Don't Tell You 1.2 H&K today - Key figures and key data of a world leading producer of small arms 1.3 Critical Company Chronicles H&K - Ascent to the World Stage 1.1 What the Offical Histories of H&K Don't Tell You In the following, the GLOBAL NET - STOP THE ARMS TRADE (GN-STAT) presents a critical analysis of the more than seventy-year history of Heckler & Koch (H&K) - the deadliest company in Europe, measured by the number of its victims: Heckler & Koch is still trying to spread the cloak of silence and forgetting over the dramatic consequences of their arms export and licensing practices. This willful ignorance is also displayed in the two official works on the company's history: On the one hand, the digital "chronicle" of the company on the company's homepage is extremely short and covers only a few events which are seen as positive from the company’s perspective (see https://www.heckler-koch.com/de/unternehmen/historie.html). On the other hand, the book by Manfred Kersten and Walter Schmid, published in 1999: "Heckler & Koch: The official history of the Oberndorf company Heckler & Koch" on 383 pages describes the development of the Oberndorf arms manufacturers up to the end of the last century in a differentiated but one-sided, company-friendly manner. -

Foreign Military Weapons and Equipment

DEPARTMENT OF THE ARMY PAMPHLET NO. 30-7-4 FOREIGN MILITARY WEAPONS AND EQUIPMENT Vol. III INFANTRY WEAPONS DEPARTMENT OF THE ARMY DT WASHINGTON 25, D. C. FOREWORD The object in publishing the essential recognition features of weapons of Austrian, German, and Japanese origin as advance sections of DA Pam 30-7-4 is to present technical information on these weapons as they are used or held in significant quantities by the Soviet satellite nations (see DA Pam 30-7-2). The publication is in looseleaf form to facilitate inclusion of additional material when the remaining sections of DA Pam 30-7-4 are published. Items are presented according to country of manufacture. It should be noted that, although they may be in use or held in reserve by a satellite country, they may be regarded as obsolete in the country of manufacture. DA Pam 30-7-4 PAMPHLET DEPARTMENT OF THE ARMY No. 30-7-4 WASHINGTON 25, D. C., 24 November 1954 FOREIGN MILITARY WEAPONS AND EQUIPMENT VOL. III INFANTRY WEAPONS SECTION IV. OTHER COUNTRIES AUSTRIA: Page Glossary of Austrian terms--------------------------------------------------------- 4 A. Pistols: 9-mm Pistol M12 (Steyr) ---------------------------------------------------- 5 B. Submachine Guns: 9-mm Submachine Gun MP 34 (Steyr-Solothurn) ------------------------------- .7 C. Rifles and Carbines: 8-mm M1895 Mannlicher Rifle- - ____________________________________- - - - - - -- 9 GERMANY: Glossary of German terms___________________________________---------------------------------------------------------11 A. Pistols: 9-mm Walther Pistol M1938-- _______________________-- - --- -- -- 13 9-mm Luger Pistol M1908--------------------------------------------------15 7.65-mm Sauer Pistol M1938---------------------------------_ 17 7.65-mm Walther Pistol Model PP and PPK ---------------------------------- 19 7.63-mm Mauser Pistol M1932----------------------------------------------21 7.65-mm Mauser Pistol Model HSc ------------------------------------------ 23 B. -

A FREE PAPER for the PEOPLE WHO FIND THEMSELVES in the ANNAPOLIS VALLEY October 1 – 15, 2015 | Issue No

1 October 1 – 15, 2015 A FREE PAPER FOR THE PEOPLE WHO FIND THEMSELVES IN THE ANNAPOLIS VALLEY October 1 – 15, 2015 | Issue No. 12.20 ARTS CULTURE COMMUNITY You're holding one of 5700 copies Grow Your Own Clothes – p.3 55 Years of Apple Farming – p.11 Valley Harvest Marathon – p.11 Your Political Questions – p.12 AppleFest in Berwick – p.13 Zucchini Lasagna ••••••• – p.14 ••• Michelle Herx – p.16 Fall into Autumn – p.18 PAGE 2 REG 2 October 1 – 15, 2015 ON THE COVER Of all the amazing bounty of crops that au- food to be truly grateful for, and all produced tumn brings to our beautiful Annapolis Valley, locally by the dedicated farmers of our Annap- there is perhaps nothing more lovely than the olis Valley. These bins of crisp, red apples are Valley’s namesake fruit. Each fall when the air the product of Killam Orchard in Woodville, starts to cool and the apples are ripe, ready to land proudly worked by four generations of be picked, you know that Thanksgiving is just the Killam family. around the corner. Applesauce, apple cider, and, of course, apple pie...mouth-watering Photo by Jocelyn Hatt Grand Pré Wines Wine Fest 2015 October 10-11 12 - 4pm Live music from 12-4 Free tours and tastings at 11am, 3pm and 5pm Oyster Bar, Raclette, Sausages 2,000 Bonus reward miles. To apply, visit us at: Wolfville Branch, All new product release That’s two tickets! 424 Main St. ® ®† ®* 902-542-7177 o r BMO AIR MILES World MasterCard Stop waiting.