Isopoda, Oniscidea: Trichoniscidae) from Bedfordshire and Derbyshire

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Faunistic Survey of Terrestrial Isopods (Isopoda: Oniscidea) in the Boč Massif Area

NATURA SLOVENIAE 16(1): 5-14 Prejeto / Received: 5.2.2014 SCIENTIFIC PAPER Sprejeto / Accepted: 19.5.2014 Faunistic survey of terrestrial isopods (Isopoda: Oniscidea) in the Boč Massif area Blanka RAVNJAK & Ivan KOS Department of Biology, Biotechnical Faculty, University of Ljubljana, Večna pot 111, SI-1000 Ljubljana, Slovenia; E-mails: [email protected], [email protected] Abstract. In 2005, terrestrial isopods were sampled in the Boč Massif area, eastern Slovenia, and their fauna compared at five different sampling sites: forest on dolomite, forest on limestone, thermophilous forest, young stage forest and extensive meadow. Two sampling methods were used: hand collecting and quadrate soil sampling with a subsequent heat extraction of animals. The highest species diversity (8 species) was recorded in the forest on dolomite and in young stage forest. No isopod species were found in samples from the extensive meadow. In the entire study area we recorded 12 different terrestrial isopod species and caught 109 specimens in total. The research brought new data on the distribution of two quite poorly known species in Slovenia: the Trachelipus razzauti and Haplophthalmus abbreviatus. Key words: species structure, terrestrial isopods, Boč Massif, Slovenia Izvleček. Favnistični pregled mokric (Isopoda: Oniscidea) na območju Boškega masiva – Leta 2005 smo na območju Boškega masiva v vzhodni Sloveniji opravili vzorčenje favne mokric. V raziskavi smo primerjali favno mokric na petih različnih vzorčnih mestih: v gozdu na dolomitu, v gozdu na apnencu, termofilnem gozdu, mladem gozdu in na ekstenzivnem travniku. Vzorčili smo z dvema metodama, in sicer z metodo ročnega pobiranja ter z odvzemom talnih vzorcev po metodi kvadratov. -

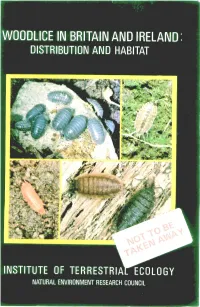

Woodlice in Britain and Ireland: Distribution and Habitat Is out of Date Very Quickly, and That They Will Soon Be Writing the Second Edition

• • • • • • I att,AZ /• •• 21 - • '11 n4I3 - • v., -hi / NT I- r Arty 1 4' I, • • I • A • • • Printed in Great Britain by Lavenham Press NERC Copyright 1985 Published in 1985 by Institute of Terrestrial Ecology Administrative Headquarters Monks Wood Experimental Station Abbots Ripton HUNTINGDON PE17 2LS ISBN 0 904282 85 6 COVER ILLUSTRATIONS Top left: Armadillidium depressum Top right: Philoscia muscorum Bottom left: Androniscus dentiger Bottom right: Porcellio scaber (2 colour forms) The photographs are reproduced by kind permission of R E Jones/Frank Lane The Institute of Terrestrial Ecology (ITE) was established in 1973, from the former Nature Conservancy's research stations and staff, joined later by the Institute of Tree Biology and the Culture Centre of Algae and Protozoa. ITE contributes to, and draws upon, the collective knowledge of the 13 sister institutes which make up the Natural Environment Research Council, spanning all the environmental sciences. The Institute studies the factors determining the structure, composition and processes of land and freshwater systems, and of individual plant and animal species. It is developing a sounder scientific basis for predicting and modelling environmental trends arising from natural or man- made change. The results of this research are available to those responsible for the protection, management and wise use of our natural resources. One quarter of ITE's work is research commissioned by customers, such as the Department of Environment, the European Economic Community, the Nature Conservancy Council and the Overseas Development Administration. The remainder is fundamental research supported by NERC. ITE's expertise is widely used by international organizations in overseas projects and programmes of research. -

Orden Isopoda: Suborden Oniscidea

Revista IDE@ - SEA, nº 78 (30-06-2015): 1–12. ISSN 2386-7183 1 Ibero Diversidad Entomológica @ccesible www.sea-entomologia.org/IDE@ Clase: Malacostraca Orden ISOPODA: Oniscidea Manual CLASE MALACOSTRACA Orden Isopoda: Suborden Oniscidea Lluc Garcia *Museu Balear de Ciències Naturals, Sóller, Mallorca (Illes Balears) Imagen superior: Oniscus asellus. Fotografía LL. Garcia 1. Breve definición del grupo y principales caracteres diagnósticos 1.1. Morfología. Generalidades. Los isópodos terrestres (Oniscidea) son crustáceos eumalacostráceos pertenecientes al orden Isopoda, aunque reúnen una serie de características morfológicas y fisiológicas relacionadas con su modo de vida terrestre que permiten considerarlos como un grupo natural bien definido, considerado actualmente como monofilético (Schmidt, 2002, 2003, 2008). Como todos los representantes del orden, su cuerpo está dor- soventralmente aplanado y se divide en tres partes bien diferenciables a simple vista: 1. El céfalon, en el que sitúan los ojos, en la mayoría de los casos compuestos; dos pares de ante- nas; y el aparato masticador con un par de mandíbulas, que son asimétricas, y dos pares de maxilas. En los isópodos terrestres el céfalon está compuesto por la cabeza propiamente dicha y por el primer seg- mento del pereion, soldado a ésta y llamado también segmento maxilipedal por insertarse en él los maxilí- pedos, que cubren el resto de piezas bucales. La división entre este segmento y el resto de la cabeza es invisible en vista dorsal en la gran mayoría de isópodos terrestres aunque sí que es apreciable en forma surcos laterales que lo separan de la región cefálica. Por eso se debe considerar más propiamente como un cefalotórax. -

Incipient Non-Adaptive Radiation by Founder Effect? Oliarus Polyphemus Fennah, 1973 – a Subterranean Model Case

Incipient non-adaptive radiation by founder effect? Oliarus polyphemus Fennah, 1973 – a subterranean model case. (Hemiptera: Fulgoromorpha: Cixiidae) Dissertation zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades doctor rerum naturalium (Dr. rer. nat.) im Fach Biologie eingereicht an der Mathematisch-Naturwissenschaftlichen Fakultät I der Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin von Diplom-Biologe Andreas Wessel geb. 30.11.1973 in Berlin Präsident der Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin Prof. Dr. Christoph Markschies Dekan der Mathematisch-Naturwissenschaftlichen Fakultät I Prof. Dr. Lutz-Helmut Schön Gutachter/innen: 1. Prof. Dr. Hannelore Hoch 2. Prof. Dr. Dr. h.c. mult. Günter Tembrock 3. Prof. Dr. Kenneth Y. Kaneshiro Tag der mündlichen Prüfung: 20. Februar 2009 Incipient non-adaptive radiation by founder effect? Oliarus polyphemus Fennah, 1973 – a subterranean model case. (Hemiptera: Fulgoromorpha: Cixiidae) Doctoral Thesis by Andreas Wessel Humboldt University Berlin 2008 Dedicated to Francis G. Howarth, godfather of Hawai'ian cave ecosystems, and to the late Hampton L. Carson, who inspired modern population thinking. Ua mau ke ea o ka aina i ka pono. Zusammenfassung Die vorliegende Arbeit hat sich zum Ziel gesetzt, den Populationskomplex der hawai’ischen Höhlenzikade Oliarus polyphemus als Modellsystem für das Stu- dium schneller Artenbildungsprozesse zu erschließen. Dazu wurde ein theoretischer Rahmen aus Konzepten und daraus abgeleiteten Hypothesen zur Interpretation be- kannter Fakten und Erhebung neuer Daten entwickelt. Im Laufe der Studie wurde zur Erfassung geografischer Muster ein GIS (Geographical Information System) erstellt, das durch Einbeziehung der historischen Geologie eine präzise zeitliche Einordnung von Prozessen der Habitatsukzession erlaubt. Die Muster der biologi- schen Differenzierung der Populationen wurden durch morphometrische, etho- metrische (bioakustische) und molekulargenetische Methoden erfasst. -

Malacostraca, Isopoda, Oniscidea) of Nature Reserves in Poland

B ALTIC COASTAL ZONE Vol. 24 pp. 65–71 2020 ISSN 2083-5485 © Copyright by Institute of Modern Languages of the Pomeranian University in Słupsk Received: 7/04/2021 Original research paper Accepted: 26/05/2021 NEW INFORMATION ON THE WOODLOUSE FAUNA (MALACOSTRACA, ISOPODA, ONISCIDEA) OF NATURE RESERVES IN POLAND Artsiom M. Ostrovsky1, Oleg R. Aleksandrowicz2 1 Gomel State Medical University, Belarus e-mail: [email protected] 2 Institute of Biology and Earth Sciences, Pomeranian University in Słupsk, Poland e-mail: [email protected] Abstract This is the fi rst study on the woodlouse fauna of from 5 nature reserves in the Mazowian Lowland (Bukowiec Jabłonowski, Mosty Kalińskie, Łosiowe Błota, Jezioro Kiełpińskie, Klimonty) and from 2 nature reserves in the Pomeranian Lake District (Ustronie, Dolina Huczka) are presented. A total of 8 species of woodlice were found. The number of collected species ranged from 1 (Dolina Chuczka, Mosty Kalińskie, Klimonty) to 5 (Łosiowe Błota). The most common species in the all studied reserves was Trachelipus rathkii. Key words: woodlouse fauna, nature reserves, Poland, Isopoda, species INTRODUCTION Woodlice are key organisms for nutrient cycling in many terrestrial ecosystems; how- ever, knowledge on this invertebrate group is limited as for other soil fauna taxa. By 2004, the world’s woodlouse fauna (Isopoda, Oniscidea) included 3637 valid species (Schmalfuss 2003). The fauna of terrestrial isopods in Europe has been active studied since the beginning of the XX century and is now well studied (Jeff ery et al. 2010). In Poland 37 isopod species inhabiting terrestrial habitats have been recorded so far, including 12 in Mazovia and 16 in Pomerania (Jędryczkowski 1979, 1981, Razowski 1997, Piksa and Farkas 2007, Astrouski and Aleksandrowicz 2018). -

Notes on Terrestrial Isopoda Collected in Dutch Greenhouses

NOTES ON TERRESTRIAL ISOPODA COLLECTED IN DUTCH GREENHOUSES by L. B. HOLTHUIS On the initiative of Dr. A. D. J. Meeuse investigations were made on the fauna of the greenhouses of several Botanic Gardens in the Netherlands; material was also collected in greenhouses of other institutions and in those kept for commercial purposes. The isopods contained in the col• lection afforded many interesting species, so for instance six of the species are new for the Dutch fauna, viz., Trichoniscus pygmaeus Sars, Hylonis- cus riparius (Koch), Cordioniscus stebbingi (Patience), Chaetophiloscia balssi Verhoeff, Trichorhina monocellata Meinertz and Nagara cristata (Dollfus). Before the systematic review of the species a list of the localities from which material was obtained is given here with enumeration of the collected species. 1. Greenhouses of the Botanic Gardens, Amsterdam; October 24, 1942; leg. A. D. J. Meeuse (Cordioniscus stebbingi, Chaetophiloscia balssi, Por- cellio scaber, Nagara cristata, Armadillidium vulgare). 2. Greenhouses of the "Laboratorium voor Bloembollenonderzoek,, (Laboratory for Bulb Research), Lisse; June 13, 1943; leg. A. D. J. Meeuse (Oniscus asellus, Porcellio scaber, Porcellionides pruinosus, Ar• madillidium vulgare, Armadillidium nasutum). 3. Greenhouses of the Botanic Gardens, Leiden; May, 1924-November, 1942. leg. H. C. Blote, L. B. Holthuis, F. P. Koumans, A. D. J. Meeuse, A. L. J. Sunier and W. Vervoort (Androniscus dentiger, Cordioniscus stebbingi, Haplophthalmus danicus, Oniscus asellus, Porcellio scaber, For- cellionides pruinosus, Armadillidium vulgare, Armadillidium nasutum), 4. Greenhouses of the Zoological Gardens, The Hague; November 4, 1942; leg. A. D. J. Meeuse (Cordioniscus stebbingi, Oniscus asellus, Por• cellio dilatatus). 5. Greenhouse for grape culture, Loosduinen, near The Hague; October 30, 1942; leg. -

Curriculum Vitae (PDF)

CURRICULUM VITAE Steven J. Taylor April 2020 Colorado Springs, Colorado 80903 [email protected] Cell: 217-714-2871 EDUCATION: Ph.D. in Zoology May 1996. Department of Zoology, Southern Illinois University, Carbondale, Illinois; Dr. J. E. McPherson, Chair. M.S. in Biology August 1987. Department of Biology, Texas A&M University, College Station, Texas; Dr. Merrill H. Sweet, Chair. B.A. with Distinction in Biology 1983. Hendrix College, Conway, Arkansas. PROFESSIONAL AFFILIATIONS: • Associate Research Professor, Colorado College (Fall 2017 – April 2020) • Research Associate, Zoology Department, Denver Museum of Nature & Science (January 1, 2018 – December 31, 2020) • Research Affiliate, Illinois Natural History Survey, Prairie Research Institute, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign (16 February 2018 – present) • Department of Entomology, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign (2005 – present) • Department of Animal Biology, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign (March 2016 – July 2017) • Program in Ecology, Evolution, and Conservation Biology (PEEC), School of Integrative Biology, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign (December 2011 – July 2017) • Department of Zoology, Southern Illinois University at Carbondale (2005 – July 2017) • Department of Natural Resources and Environmental Sciences, University of Illinois at Urbana- Champaign (2004 – 2007) PEER REVIEWED PUBLICATIONS: Swanson, D.R., S.W. Heads, S.J. Taylor, and Y. Wang. A new remarkably preserved fossil assassin bug (Insecta: Heteroptera: Reduviidae) from the Eocene Green River Formation of Colorado. Palaeontology or Papers in Palaeontology (Submitted 13 February 2020) Cable, A.B., J.M. O’Keefe, J.L. Deppe, T.C. Hohoff, S.J. Taylor, M.A. Davis. Habitat suitability and connectivity modeling reveal priority areas for Indiana bat (Myotis sodalis) conservation in a complex habitat mosaic. -

Ecological and Zoogeographical Significance of Terrestrial Isopods from the Carei Plain Natural Reserve (Romania)

Arch. Biol. Sci., Belgrade, 64 (3), 1029-1036, 2012 DOI:10.2298/ABS1203029F ECOLOGICAL AND ZOOGEOGRAPHICAL SIGNIFICANCE OF TERRESTRIAL ISOPODS FROM THE CAREI PLAIN NATURAL RESERVE (ROMANIA) SÁRA FERENŢI1,2,*, DIANA CUPSA 2 and S.-D. COVACIU-MARCOV2 1 Babes-Bolyai University, Faculty of Biology and Geology, Department of Biology, 400015 Cluj-Napoca, Romania 2 University of Oradea, Faculty of Sciences, Department of Biology, 410087 Oradea, Romania Abstract - In the Carei Plain natural reserve we identified 15 terrestrial isopod species: Haplophthalmus mengii, Hap- lophthalmus danicus, Hyloniscus riparius, Hyloniscus transsylvanicus, Plathyarthrus hoffmannseggii, Cylisticus convexus, Porcellionides pruinosus, Protracheoniscus politus, Trachelipus arcuatus, Trachelipus nodulosus, Trachelipus rathkii, Porcel- lium collicola, Porcellio scaber, Armadillidium vulgare and Armadillidium versicolor. The highest species diversity is found in wetlands, while the lowest is in plantations and forests. On the Carei Plain, there are some terrestrial isopods that are normally connected with higher altitudes. Moreover, some sylvan species are present in the open wetlands. Unlike marshes, sand dunes present anthropophilic and invasive species. The diversity of the terrestrial isopods from the Carei Plain protected area is high due to the habitats’ diversity and the history of this area. Thus, the composition of the terres- trial isopod communities from the area underlines its distinct particularities, emphasizing the necessity of preserving the natural habitats. Key words: Terrestrial isopods, diversity, habitats, wetlands, anthropogenic influence, protected area, Romania INTRODUCTION ing the number of protected areas (Iojă et al. 2010), there are few studies of terrestrial isopods (Tomescu, At present, the protection level of organisms is highly 1992; Tomescu et al., 1995, 2011; Giurginca et al., influenced by their taxonomic position and complex- 2006, 2007). -

Complementary Distribution Patterns of Arthropod Detritivores (Woodlice and Millipedes) Along Forest Edge‐To

Insect Conservation and Diversity (2016) 9, 456–469 doi: 10.1111/icad.12183 Complementary distribution patterns of arthropod detritivores (woodlice and millipedes) along forest edge-to-interior gradients PALLIETER DE SMEDT,1 KAREN WUYTS,2 LANDER BAETEN,1 AN DE SCHRIJVER,1 WILLEM PROESMANS,1 PIETER DE FRENNE,1 EVY AMPOORTER,1 ELYN REMY,1 MERLIJN GIJBELS,1 MARTIN HERMY,3 4 1 DRIES BONTE andKRISVERHEYEN 1Forest & Nature Lab, Department of Forest and Water management, Ghent University, Melle (Gontrode), Belgium, 2ENdEMIC Research Group, Department of Bioscience Engineering, University of Antwerp, Antwerp, Belgium, 3Division Forest, Nature and Landscape, Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences, University of Leuven, Leuven, Belgium and 4Terrestrial Ecology Unit (TEREC), Department of Biology, Ghent University, Ghent, Belgium Abstract. 1. Worldwide, forest fragmentation induces edge effects, thereby strongly altering the forest microclimate and abiotic characteristics in the forest edge compared to the forest interior. The impact of edge-to-interior gradients on abiotic parameters has been extensively studied, but we lack insights on how biodiversity, and soil communities in particular, are structured along these gra- dients. 2. Woodlice (Isopoda) and millipedes (Diplopoda) are dominant macro-detriti- vores in temperate forests with acidic sandy soils. 3. We investigated the distribution of these macro-detritivores along forest edge-to-interior gradients in six different forest stands with sandy soils in north- ern Belgium. 4. Woodlouse abundance decreased exponentially with distance from the for- est edge, whereas millipede abundance did not begin to decrease until 7 m inside the forest stands. Overall, these patterns were highly species specific and could be linked to the species’ desiccation tolerance. -

Isopoda: Oniscidea: Trichoniscidae) on the West Coast of Britain Frank Ashwood1 and Steve J

Bulletin of the British Myriapod & Isopod Group Volume 33 (2021) Observations of Trichoniscoides sarsi Patience, 1908 (Isopoda: Oniscidea: Trichoniscidae) on the west coast of Britain Frank Ashwood1 and Steve J. Gregory2 1 E-mail: [email protected] 2 4 Mount Pleasant, Church Street, East Hendred, Oxfordshire OX12 8LA, UK. E-mail: [email protected] Abstract Here we report two observations of Trichoniscoides sarsi Patience in western Britain from a synanthropic allotment in Bristol city and from semi-natural coastal habitat near Clevedon. We highlight possible confusion between coastal observations of T. sarsi and its congener T. saeroeensis Lohmander, which has been widely recorded around the entire British coastline (Gregory, 2009). These findings emphasise that all red-eyed Trichoniscoides found on the coast of Britain cannot be assumed to be T. saeroeensis, and reliable determination of all Trichoniscoides species can only be based on examination of male specimens, regardless of where specimens are found. Key words: Isopoda, Oniscidea, Trichoniscoides sarsi, Britain, Distribution, Habitat. Introduction The elusive woodlouse Trichoniscoides sarsi Patience appears to have an odd distribution in Britain and Ireland. The map published in Gregory (2009) shows a distinct band of localities stretching across eastern England from Kent to Suffolk and then extending westwards across central England through Leicestershire and into Shropshire with an isolated record near Dublin, eastern Ireland (yellow circles in Fig. 4). Subsequently this distribution pattern has been reinforced by the discovery of T. sarsi in Bedfordshire, Derbyshire, Lincolnshire and Essex (Richards, 2016; Gregory, 2018; 2019b). However, the discovery of T. sarsi on the Scottish east coast of Kincardineshire (Davidson, 2011), some 400 km north of previously known Leicestershire records, and more recently in a garden in west Lancashire (Gregory, 2019a) suggest a much wider distribution (orange circles in Fig. -

Annotated Checklist of the Isopoda (Subphylum Crustacea: Class Malacostraca) of Arkansas and Oklahoma, with Emphasis Upon Subterranean Habitats

1 Annotated Checklist of the Isopoda (Subphylum Crustacea: Class Malacostraca) of Arkansas and Oklahoma, with Emphasis Upon Subterranean Habitats G. O. Graening Department of Biological Sciences, California State University at Sacramento, Sacramento, CA 95819 Michael E. Slay Arkansas Field Office, The Nature Conservancy, 601 North University Avenue, Little Rock, AR 72205 Danté B. Fenolio Department of Biology, University of Miami, 1301 Memorial Drive, Coral Gables, FL 33124 Henry W. Robison Department of Biology, Southern Arkansas University, Magnolia, AR 71754 All known records of isopod crustaceans (Order Isopoda) in the states of Arkansas and Oklahoma are summarized, including new state, county, and site records. This updated checklist recognizes 47 taxa in 9 families: 2 taxa in Armadillidiidae; 1 in Armadillidae; 30 in Asellidae; 1 in Cylisticidae; 1 in Ligiidae; 1 in Oniscidae; 4 in Porcellionidae; 1 in Trachelipodidae; and 6 in Trichoniscidae. This faunal inventory includes 17 taxa that are subterranean obligates (troglobites or stygobites), and 14 taxa that are endemic to this geographical region. Current distributions and conservation statuses are summarized, and new rarity rankings are suggested. © 2007 Oklahoma Academy of Science INTRODUCTION these two states are closely associated with subterranean habitats, and those species This study assembles the first checklist restricted to hypogean habitats are typically of the entire Order Isopoda (Subphylum troglomorphic (i.e., exhibiting loss of pig- Crustacea: Class Malacostraca) -

1 the RESTRUCTURING of ARTHROPOD TROPHIC RELATIONSHIPS in RESPONSE to PLANT INVASION by Adam B. Mitchell a Dissertation Submitt

THE RESTRUCTURING OF ARTHROPOD TROPHIC RELATIONSHIPS IN RESPONSE TO PLANT INVASION by Adam B. Mitchell 1 A dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the University of Delaware in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Entomology and Wildlife Ecology Winter 2019 © Adam B. Mitchell All Rights Reserved THE RESTRUCTURING OF ARTHROPOD TROPHIC RELATIONSHIPS IN RESPONSE TO PLANT INVASION by Adam B. Mitchell Approved: ______________________________________________________ Jacob L. Bowman, Ph.D. Chair of the Department of Entomology and Wildlife Ecology Approved: ______________________________________________________ Mark W. Rieger, Ph.D. Dean of the College of Agriculture and Natural Resources Approved: ______________________________________________________ Douglas J. Doren, Ph.D. Interim Vice Provost for Graduate and Professional Education I certify that I have read this dissertation and that in my opinion it meets the academic and professional standard required by the University as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Signed: ______________________________________________________ Douglas W. Tallamy, Ph.D. Professor in charge of dissertation I certify that I have read this dissertation and that in my opinion it meets the academic and professional standard required by the University as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Signed: ______________________________________________________ Charles R. Bartlett, Ph.D. Member of dissertation committee I certify that I have read this dissertation and that in my opinion it meets the academic and professional standard required by the University as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Signed: ______________________________________________________ Jeffery J. Buler, Ph.D. Member of dissertation committee I certify that I have read this dissertation and that in my opinion it meets the academic and professional standard required by the University as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy.