Status of the Prey Species of the Leopard in the Caucasus

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alpine Ibex, Capra Ibex

(CAPRA IBEX) ALPINE IBEX by: Braden Stremcha EVOLUTION Alpine ibex is part of the Bovidae family under the order Artiodactyla. The Capra genus signifies this species specifically as a wild goat, but this genus shares very similar evolutionary features as species we recognize in Montana like Oreamnos (mountain goat) and Ovis (sheep). Capra, Oreamnos, and Ovis most likely derived in evolution from each other due to glacial migration and failure to hybridize between genera and species.Capra ibex was first historically observed throughout the central Alpine Range of Europe, then was decreased to Grand Paradiso National Park in Italy and the Maurienne Valley in France but has since been reintroduced in multiple other countries across the Alps. FORM AND FUNCTION Capra ibex shares a typical hoofed unguligrade foot posture, a cannon bone with raised calcaneus, and the common cursorial locomotion associated with species in Artiodactyla. These features allow the alpine ibex to maneuver through the steep terrain in which they reside. Specifically, for alpine ungulates and the alpine ibex, more energy is put into balance and strength to stay on uneven terrain than moving long distances. Alpine ibexes are often observed climbing artificial dams that are almost vertical to lick mineral deposits! This example shows how efficient Capra ibex is at navigating steep and dangerous terrain. The most visual distinction that sets the Capra genus apart from others is the large, elongated semicircular horns. Alpine ibex specifically has horns that grow throughout their life span at an average of 80mm per year in males. When winter comes around this growth is stunted until spring and creates an obvious ring on the horn that signifies that year’s overall growth. -

Panthera Pardus, Leopard

The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species™ ISSN 2307-8235 (online) IUCN 2008: T15954A5329380 Panthera pardus, Leopard Assessment by: Henschel, P., Hunter, L., Breitenmoser, U., Purchase, N., Packer, C., Khorozyan, I., Bauer, H., Marker, L., Sogbohossou, E. & Breitenmoser- Wursten, C. View on www.iucnredlist.org Citation: Henschel, P., Hunter, L., Breitenmoser, U., Purchase, N., Packer, C., Khorozyan, I., Bauer, H., Marker, L., Sogbohossou, E. & Breitenmoser-Wursten, C. 2008. Panthera pardus. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2008: e.T15954A5329380. http://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2008.RLTS.T15954A5329380.en Copyright: © 2015 International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources Reproduction of this publication for educational or other non-commercial purposes is authorized without prior written permission from the copyright holder provided the source is fully acknowledged. Reproduction of this publication for resale, reposting or other commercial purposes is prohibited without prior written permission from the copyright holder. For further details see Terms of Use. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species™ is produced and managed by the IUCN Global Species Programme, the IUCN Species Survival Commission (SSC) and The IUCN Red List Partnership. The IUCN Red List Partners are: BirdLife International; Botanic Gardens Conservation International; Conservation International; Microsoft; NatureServe; Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew; Sapienza University of Rome; Texas A&M University; Wildscreen; and Zoological Society of London. If you see any errors or have any questions or suggestions on what is shown in this document, please provide us with feedback so that we can correct or extend the information provided. THE IUCN RED LIST OF THREATENED SPECIES™ Taxonomy Kingdom Phylum Class Order Family Animalia Chordata Mammalia Carnivora Felidae Taxon Name: Panthera pardus (Linnaeus, 1758) Synonym(s): • Felis pardus Linnaeus, 1758 Regional Assessments: • Mediterranean Infra-specific Taxa Assessed: • Panthera pardus ssp. -

BIGHORN SHEEP Ovis Canadensis Original1 Prepared by R.A

BIGHORN SHEEP Ovis canadensis Original1 prepared by R.A. Demarchi Species Information Distribution Global Taxonomy The genus Ovis is present in west-central Asia, Until recently, three species of Bighorn Sheep were Siberia, and North America (and widely introduced recognized in North America: California Bighorn in Europe). Approximately 38 000 Rocky Mountain Sheep (Ovis canadensis californiana), Rocky Bighorn Sheep (Wishart 1999) are distributed in Mountain Bighorn Sheep (O. canadensis canadensis), scattered patches along the Rocky Mountains of and Desert Bighorn Sheep (O. canadensis nelsoni). As North America from west of Grand Cache, Alberta, a result of morphometric measurements, and to northern New Mexico. They are more abundant protein and mtDNA analysis, Ramey (1995, 1999) and continuously distributed in the rainshadow of recommended that only Desert Bighorn Sheep and the eastern slopes of the Continental Divide the Sierra Nevada population of California Bighorn throughout their range. Sheep be recognized as separate subspecies. California Bighorn Sheep were extirpated from most Currently, California and Rocky Mountain Bighorn of the United States by epizootic disease contracted sheep are managed as separate ecotypes in British from domestic sheep in the 1800s with a small Columbia. number living in California until 1954 (Buechner Description 1960). Since 1954, Bighorn Sheep have been reintroduced from British Columbia to California, California Bighorn Sheep are slightly smaller than Idaho, Nevada, North Dakota, Oregon, Utah, and mature Rocky Mountain Bighorn Sheep Washington, resulting in their re-establishment in (McTaggart-Cowan and Guiguet 1965). Like their much of their historic range. By 1998, California Rocky Mountain counterpart, California Bighorn Bighorn Sheep were estimated to number 10 000 Sheep have a dark to medium rich brown head, neck, (Toweill 1999). -

Favourableness and Connectivity of a Western Iberian Landscape for the Reintroduction of the Iconic Iberian Ibex Capra Pyrenaica

Favourableness and connectivity of a Western Iberian landscape for the reintroduction of the iconic Iberian ibex Capra pyrenaica R ITA T. TORRES,JOÃO C ARVALHO,EMMANUEL S ERRANO,WOUTER H ELMER P ELAYO A CEVEDO and C ARLOS F ONSECA Abstract Traditional land use practices declined through- Keywords Capra pyrenaica, environmental favourableness, out many of Europe’s rural landscapes during the th cen- graph theory, habitat connectivity, Iberian ibex, reintroduc- tury. Rewilding (i.e. restoring ecosystem functioning with tion, ungulate minimal human intervention) is being pursued in many areas, and restocking or reintroduction of key species is often part of the rewilding strategy. Such programmes re- Introduction quire ecological information about the target areas but this is not always available. Using the example of the an has shaped landscapes for centuries (Vos & Iberian ibex Capra pyrenaica within the Rewilding Europe Meekes, ). In the last decades socio-economic M framework we address the following questions: ( ) Are and lifestyle changes have driven a rural exodus and the there areas in Western Iberia that are environmentally fa- abandonment of land throughout many of Europe’s rural vourable for reintroduction of the species? ( ) If so, are landscapes (MacDonald et al., ; Höchtl et al., ). these areas well connected with each other? ( ) Which of In some cases sociocultural and economic problems have these areas favour the establishment and expansion of a vi- created new opportunities for conservation (Theil et al., ). able population -

Status and Protection of Globally Threatened Species in the Caucasus

STATUS AND PROTECTION OF GLOBALLY THREATENED SPECIES IN THE CAUCASUS CEPF Biodiversity Investments in the Caucasus Hotspot 2004-2009 Edited by Nugzar Zazanashvili and David Mallon Tbilisi 2009 The contents of this book do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of CEPF, WWF, or their sponsoring organizations. Neither the CEPF, WWF nor any other entities thereof, assumes any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of any information, product or process disclosed in this book. Citation: Zazanashvili, N. and Mallon, D. (Editors) 2009. Status and Protection of Globally Threatened Species in the Caucasus. Tbilisi: CEPF, WWF. Contour Ltd., 232 pp. ISBN 978-9941-0-2203-6 Design and printing Contour Ltd. 8, Kargareteli st., 0164 Tbilisi, Georgia December 2009 The Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund (CEPF) is a joint initiative of l’Agence Française de Développement, Conservation International, the Global Environment Facility, the Government of Japan, the MacArthur Foundation and the World Bank. This book shows the effort of the Caucasus NGOs, experts, scientific institutions and governmental agencies for conserving globally threatened species in the Caucasus: CEPF investments in the region made it possible for the first time to carry out simultaneous assessments of species’ populations at national and regional scales, setting up strategies and developing action plans for their survival, as well as implementation of some urgent conservation measures. Contents Foreword 7 Acknowledgments 8 Introduction CEPF Investment in the Caucasus Hotspot A. W. Tordoff, N. Zazanashvili, M. Bitsadze, K. Manvelyan, E. Askerov, V. Krever, S. Kalem, B. Avcioglu, S. Galstyan and R. Mnatsekanov 9 The Caucasus Hotspot N. -

Capture, Restraint and Transport Stress in Southern Chamois (Rupicapra Pyrenaica)

Capture,Capture, restraintrestraint andand transporttransport stressstress ininin SouthernSouthern chamoischamois ((RupicapraRupicapra pyrenaicapyrenaica)) ModulationModulation withwith acepromazineacepromazine andand evaluationevaluation usingusingusing physiologicalphysiologicalphysiological parametersparametersparameters JorgeJorgeJorge RamónRamónRamón LópezLópezLópez OlveraOlveraOlvera 200420042004 Capture, restraint and transport stress in Southern chamois (Rupicapra pyrenaica) Modulation with acepromazine and evaluation using physiological parameters Jorge Ramón López Olvera Bellaterra 2004 Esta tesis doctoral fue realizada gracias a la financiación de la Comisión Interministerial de Ciencia y Tecnología (proyecto CICYT AGF99- 0763-C02) y a una beca predoctoral de Formación de Investigadores de la Universidad Autónoma de Barcelona, y contó con el apoyo del Departament de Medi Ambient de la Generalitat de Catalunya. Los Doctores SANTIAGO LAVÍN GONZÁLEZ e IGNASI MARCO SÁNCHEZ, Catedrático de Universidad y Profesor Titular del Área de Conocimiento de Medicina y Cirugía Animal de la Facultad de Veterinaria de la Universidad Autónoma de Barcelona, respectivamente, CERTIFICAN: Que la memoria titulada ‘Capture, restraint and transport stress in Southern chamois (Rupicapra pyrenaica). Modulation with acepromazine and evaluation using physiological parameters’, presentada por el licenciado Don JORGE R. LÓPEZ OLVERA para la obtención del grado de Doctor en Veterinaria, se ha realizado bajo nuestra dirección y, considerándola satisfactoriamente -

Antelope, Deer, Bighorn Sheep and Mountain Goats: a Guide to the Carpals

J. Ethnobiol. 10(2):169-181 Winter 1990 ANTELOPE, DEER, BIGHORN SHEEP AND MOUNTAIN GOATS: A GUIDE TO THE CARPALS PAMELA J. FORD Mount San Antonio College 1100 North Grand Avenue Walnut, CA 91739 ABSTRACT.-Remains of antelope, deer, mountain goat, and bighorn sheep appear in archaeological sites in the North American west. Carpal bones of these animals are generally recovered in excellent condition but are rarely identified beyond the classification 1/small-sized artiodactyl." This guide, based on the analysis of over thirty modem specimens, is intended as an aid in the identifi cation of these remains for archaeological and biogeographical studies. RESUMEN.-Se han encontrado restos de antilopes, ciervos, cabras de las montanas rocosas, y de carneros cimarrones en sitios arqueol6gicos del oeste de Norte America. Huesos carpianos de estos animales se recuperan, por 10 general, en excelentes condiciones pero raramente son identificados mas alIa de la clasifi cacion "artiodactilos pequeno." Esta glia, basada en un anaIisis de mas de treinta especlmenes modemos, tiene el proposito de servir como ayuda en la identifica cion de estos restos para estudios arqueologicos y biogeogrMicos. RESUME.-On peut trouver des ossements d'antilopes, de cerfs, de chevres de montagne et de mouflons des Rocheuses, dans des sites archeologiques de la . region ouest de I'Amerique du Nord. Les os carpeins de ces animaux, generale ment en excellente condition, sont rarement identifies au dela du classement d' ,I artiodactyles de petite taille." Le but de ce guide base sur 30 specimens recents est d'aider aidentifier ces ossements pour des etudes archeologiques et biogeo graphiques. -

A Pre-Feasibility Study on Water Conveyance Routes to the Dead

A PRE-FEASIBILITY STUDY ON WATER CONVEYANCE ROUTES TO THE DEAD SEA Published by Arava Institute for Environmental Studies, Kibbutz Ketura, D.N Hevel Eilot 88840, ISRAEL. Copyright by Willner Bros. Ltd. 2013. All rights reserved. Funded by: Willner Bros Ltd. Publisher: Arava Institute for Environmental Studies Research Team: Samuel E. Willner, Dr. Clive Lipchin, Shira Kronich, Tal Amiel, Nathan Hartshorne and Shae Selix www.arava.org TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION 1 2 HISTORICAL REVIEW 5 2.1 THE EVOLUTION OF THE MED-DEAD SEA CONVEYANCE PROJECT ................................................................... 7 2.2 THE HISTORY OF THE CONVEYANCE SINCE ISRAELI INDEPENDENCE .................................................................. 9 2.3 UNITED NATIONS INTERVENTION ......................................................................................................... 12 2.4 MULTILATERAL COOPERATION ............................................................................................................ 12 3 MED-DEAD PROJECT BENEFITS 14 3.1 WATER MANAGEMENT IN ISRAEL, JORDAN AND THE PALESTINIAN AUTHORITY ............................................... 14 3.2 POWER GENERATION IN ISRAEL ........................................................................................................... 18 3.3 ENERGY SECTOR IN THE PALESTINIAN AUTHORITY .................................................................................... 20 3.4 POWER GENERATION IN JORDAN ........................................................................................................ -

(Ammotragus Lervia) in Northern Algeria? Farid Bounaceur, Naceur Benamor, Fatima Zohra Bissaad, Abedelkader Abdi, Stéphane Aulagnier

Is there a future for the last populations of Aoudad (Ammotragus lervia) in northern Algeria? Farid Bounaceur, Naceur Benamor, Fatima Zohra Bissaad, Abedelkader Abdi, Stéphane Aulagnier To cite this version: Farid Bounaceur, Naceur Benamor, Fatima Zohra Bissaad, Abedelkader Abdi, Stéphane Aulagnier. Is there a future for the last populations of Aoudad (Ammotragus lervia) in northern Algeria?. Pakistan Journal of Zoology, 2016, 48 (6), pp.1727-1731. hal-01608784 HAL Id: hal-01608784 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01608784 Submitted on 27 May 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Pakistan J. Zool., vol. 48(6), pp. 1727-1731, 2016. Is There a Future for the Last Populations of Aoudad (Ammotragus lervia) in Northern Algeria? Farid Bounaceur,1,* Naceur Benamor,1 Fatima Zohra Bissaad,2 Abedelkader Abdi1 and Stéphane Aulagnier3 1Research Team Conservation Biology in Arid and Semi Arid, Laboratory of Biotechnology and Nutrition in Semi-Arid. Faculty of Natural Sciences and Life, University Campus Karmane Ibn Khaldoun, Tiaret, Algeria 14000 2Laboratory Technologies Soft, Promotion, Physical Chemistry of Biological Materials and Biodiversity, Science Faculty, University M'Hamed Bougara, Article Information BP 35000 Boumerdes, Algeria Received 31 August 2015 3 Revised 25 February 2016 Behavior and Ecology of Wildlife, I.N.R.A., CS 52627, 31326 Accepted 23 April 2016 Castanet Tolosan Cedex, France Available online 25 September 2016 Authors’ Contribution A B S T R A C T FB conceived and designed the study. -

Genital Brucella Suis Biovar 2 Infection of Wild Boar (Sus Scrofa) Hunted in Tuscany (Italy)

microorganisms Article Genital Brucella suis Biovar 2 Infection of Wild Boar (Sus scrofa) Hunted in Tuscany (Italy) Giovanni Cilia * , Filippo Fratini , Barbara Turchi, Marta Angelini, Domenico Cerri and Fabrizio Bertelloni Department of Veterinary Science, University of Pisa, Viale delle Piagge 2, 56124 Pisa, Italy; fi[email protected] (F.F.); [email protected] (B.T.); [email protected] (M.A.); [email protected] (D.C.); [email protected] (F.B.) * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Brucellosis is a zoonosis caused by different Brucella species. Wild boar (Sus scrofa) could be infected by some species and represents an important reservoir, especially for B. suis biovar 2. This study aimed to investigate the prevalence of Brucella spp. by serological and molecular assays in wild boar hunted in Tuscany (Italy) during two hunting seasons. From 287 animals, sera, lymph nodes, livers, spleens, and reproductive system organs were collected. Within sera, 16 (5.74%) were positive to both rose bengal test (RBT) and complement fixation test (CFT), with titres ranging from 1:4 to 1:16 (corresponding to 20 and 80 ICFTU/mL, respectively). Brucella spp. DNA was detected in four lymph nodes (1.40%), five epididymides (1.74%), and one fetus pool (2.22%). All positive PCR samples belonged to Brucella suis biovar 2. The results of this investigation confirmed that wild boar represents a host for B. suis biovar. 2 and plays an important role in the epidemiology of brucellosis in central Italy. Additionally, epididymis localization confirms the possible venereal transmission. Citation: Cilia, G.; Fratini, F.; Turchi, B.; Angelini, M.; Cerri, D.; Bertelloni, Keywords: Brucella suis biovar 2; wild boar; surveillance; epidemiology; reproductive system F. -

Anaplasma Phagocytophilum and Babesia Species Of

pathogens Article Anaplasma phagocytophilum and Babesia Species of Sympatric Roe Deer (Capreolus capreolus), Fallow Deer (Dama dama), Sika Deer (Cervus nippon) and Red Deer (Cervus elaphus) in Germany Cornelia Silaghi 1,2,*, Julia Fröhlich 1, Hubert Reindl 3, Dietmar Hamel 4 and Steffen Rehbein 4 1 Institute of Comparative Tropical Medicine and Parasitology, Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München, Leopoldstr. 5, 80802 Munich, Germany; [email protected] 2 Institute of Infectology, Friedrich-Loeffler-Institut, Südufer 10, 17493 Greifswald Insel Riems, Germany 3 Tierärztliche Fachpraxis für Kleintiere, Schießtrath 12, 92709 Moosbach, Germany; [email protected] 4 Boehringer Ingelheim Vetmedica GmbH, Kathrinenhof Research Center, Walchenseestr. 8-12, 83101 Rohrdorf, Germany; [email protected] (D.H.); steff[email protected] (S.R.) * Correspondence: cornelia.silaghi@fli.de; Tel.: +49-0-383-5171-172 Received: 15 October 2020; Accepted: 18 November 2020; Published: 20 November 2020 Abstract: (1) Background: Wild cervids play an important role in transmission cycles of tick-borne pathogens; however, investigations of tick-borne pathogens in sika deer in Germany are lacking. (2) Methods: Spleen tissue of 74 sympatric wild cervids (30 roe deer, 7 fallow deer, 22 sika deer, 15 red deer) and of 27 red deer from a farm from southeastern Germany were analyzed by molecular methods for the presence of Anaplasma phagocytophilum and Babesia species. (3) Results: Anaplasma phagocytophilum and Babesia DNA was demonstrated in 90.5% and 47.3% of the 74 combined wild cervids and 14.8% and 18.5% of the farmed deer, respectively. Twelve 16S rRNA variants of A. phagocytophilum were delineated. -

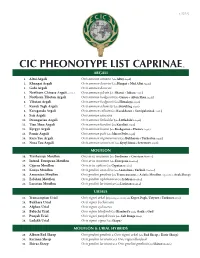

Cic Pheonotype List Caprinae©

v. 5.25.12 CIC PHEONOTYPE LIST CAPRINAE © ARGALI 1. Altai Argali Ovis ammon ammon (aka Altay Argali) 2. Khangai Argali Ovis ammon darwini (aka Hangai & Mid Altai Argali) 3. Gobi Argali Ovis ammon darwini 4. Northern Chinese Argali - extinct Ovis ammon jubata (aka Shansi & Jubata Argali) 5. Northern Tibetan Argali Ovis ammon hodgsonii (aka Gansu & Altun Shan Argali) 6. Tibetan Argali Ovis ammon hodgsonii (aka Himalaya Argali) 7. Kuruk Tagh Argali Ovis ammon adametzi (aka Kuruktag Argali) 8. Karaganda Argali Ovis ammon collium (aka Kazakhstan & Semipalatinsk Argali) 9. Sair Argali Ovis ammon sairensis 10. Dzungarian Argali Ovis ammon littledalei (aka Littledale’s Argali) 11. Tian Shan Argali Ovis ammon karelini (aka Karelini Argali) 12. Kyrgyz Argali Ovis ammon humei (aka Kashgarian & Hume’s Argali) 13. Pamir Argali Ovis ammon polii (aka Marco Polo Argali) 14. Kara Tau Argali Ovis ammon nigrimontana (aka Bukharan & Turkestan Argali) 15. Nura Tau Argali Ovis ammon severtzovi (aka Kyzyl Kum & Severtzov Argali) MOUFLON 16. Tyrrhenian Mouflon Ovis aries musimon (aka Sardinian & Corsican Mouflon) 17. Introd. European Mouflon Ovis aries musimon (aka European Mouflon) 18. Cyprus Mouflon Ovis aries ophion (aka Cyprian Mouflon) 19. Konya Mouflon Ovis gmelini anatolica (aka Anatolian & Turkish Mouflon) 20. Armenian Mouflon Ovis gmelini gmelinii (aka Transcaucasus or Asiatic Mouflon, regionally as Arak Sheep) 21. Esfahan Mouflon Ovis gmelini isphahanica (aka Isfahan Mouflon) 22. Larestan Mouflon Ovis gmelini laristanica (aka Laristan Mouflon) URIALS 23. Transcaspian Urial Ovis vignei arkal (Depending on locality aka Kopet Dagh, Ustyurt & Turkmen Urial) 24. Bukhara Urial Ovis vignei bocharensis 25. Afghan Urial Ovis vignei cycloceros 26.