Spatial Analysis of Synagogues and Churches in Nineteenth Century Whitechapel

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

JL AAAA Reviews

A COMPREHENSIVE GUIDE BOOK FOR VISITORS AND LONDONERS Rachel Kolsky and Roslyn Rawson Reviews UK Press US Press Israel Press Amazon.co.uk / Amazon.com Hebrew Other / Readers Comments CONTACT RACHEL KOLSKY [email protected] / www.golondontours.com for more information, signed copies and book events A COMPREHENSIVE GUIDE BOOK FOR VISITORS AND LONDONERS Rachel Kolsky and Roslyn Rawson Reviews UK Press Jewish London - Reviews - [email protected] - www.golondontours.com 9 THE ARCHER - www.the-archer.co.uk MARCH 2012 KALASHNIKOV KULTUR Ultimate guide to Jewish London By Ricky Savage, the voice of social irresponsibility Two authors have compiled the ultimate guide to Jewish London and will introduce it in person at a special event at the Phoenix Cinema this month. Rachel Kolsky, an Lizzie Land East Finchley resident since 1995 and a trustee of the Phoenix since 1997, co-authored Yes, it’s here, and the world of theme parks will never be Jewish London with Roslyn Rawson. the same. Why? Because the French have decided that what The 224-page guide covers holidaymakers need is a whole new experience based on where to stay, eat, shop and pray, with detailed maps, practical the life, loves and battles of a small Corsican. Welcome to advice, travel information and Napoleon Land! more than 200 colour photo- There in a eld just outside Paris you will be able to celebrate the man graphs. who conquered Europe and then lost it again, marvel at the victories, Special features include attend the glorious coronation and sign up to join the Old Guard. -

The Spatial Morphology of Synagogue Visibility As a Measure of Jewish Acculturation in Late Nineteenth-Century London

The spatial morphology of synagogue visibility as a measure of Jewish acculturation in late nineteenth- century London Laura Vaughan Space Syntax Laboratory, The Bartlett School of Architecture, University College London, 22 Gordon Street, London, WC1E 6BT, UK. E- mail: [email protected] ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0003- 0315- 2977 Revised version received 16 December 2019 Abstract. This paperʼs historical focus is the latter two decades of nineteenth- century London. During this period the established Jewish community of the city benefited from political emancipation, but this was not the case for the recently- arrived impoverished Jewish migrants from Eastern Europe. The spatial constitution of religious practice also differed across the city. A comparative study found that the more prosperous West End, other than an isolated case in the impoverished district of Soho, had purpose-built buildings fronting the street; while the poorer district of Whitechapel in the East End was dominated by smaller ad hoc arrangements – one- room or adapted premises, shtiebels – serving a wider communal and social purpose, similar to the practice of the old country. A comparative space syntax isovist analysis of the visibility of synagogue façades from surrounding streets found that while, in the West End, most synagogues had a limited public display of religious practice by this time, East End prayer houses remained visible only to their immediate, Jewish majority surroundings. This paper proposes that the amount of synagogue- street visibility corresponds to the stage of growth in both social acculturation and political confidence. Keywords: religion, immigration, visibility, isovists, synagogues, London Two large rooms knocked into one. -

Events in 5673—Introduction 221

EVENTS IN 5673—INTRODUCTION 221 EVENTS IN 5673 JULY 1, 1912, TO JUNE 30, 1913 INTRODUCTION I In the events of the year 5G73 for the Jewry, the Balkan Wars rank first. Waged with incredible brutality, they brought widespread suffering to the Jews in the former limits of the Turkish Empire. The success of the Balkan States has re- sulted in the transfer of 120,000 Jews from Turkish sov- ereignty, under which they have lived since their exile from Spain and Portugal. Servia and particularly Greece now have large Jewish communities within their territory, and the Bul- garian Jewry will be greatly enlarged. Roumania adds to her population and citizenship the Jews of Silistria. For the Balkan Jewry, the change involves new conditions, social and economic as well as political. Their situation in what was formerly Turkey in Europe, and their future, as described by the representatives of the Jewish organizations of Europe and America that united for the work of relief, cannot but be of great concern to the Jews the world over (see pp. 188-206). Notable in connection with the Balkan War are two things: the prompt and generous response of the prosperous Jewries in Western Europe and America to the Balkan distress, and the effort to secure a guarantee for the civil and political liberty and equality of the Jews in the conquered territory. An in- ternational association, the Union des Associations Israelites, 222 AMERICAN JEWISH YEAR BOOK was formed for unifying relief work and effort toward the re- habilitation of the ruined communities. Representatives were dispatched to the scene to insure systematic action, and a study made of the situation with a view to the permanent improve- ment of conditions among the 200,000 Jews in the former boundaries of Turkey in Europe. -

6280 the London. Gazette, October 3, 1902. the Naturalization Act, 1870

6280 THE LONDON. GAZETTE, OCTOBER 3, 1902. THE NATURALIZATION ACT, 1870. LIST of ALIENS to whom Certificates of Naturalization or of Readmission to British Nationality have been granted by the Secretary of State under the • provisions of the Act 33 Vic., cap. 14, and have been registered in the Home Office pursuant to the Act during the Month of September, 1902. Date of taking Name. Country. Oath of Allegiance. Place of Residence. Alper, Barnet . Russia 2nd September, 1902 Liverpool, 2, Crown-place Antipitzky, Jacob Russia 22nd September, 1902 London, 67, Tavistock-crescent, Kensington Ariowitsch, Marcus Germany . 4th September, 1902 Essex, the Limes, Upper Waltham- •' stow-road, Walthamstow Aronovitch, Solomon . Russia 19th September, 1902 Limerick, 26, Bowman-street, . Ashiroowitz, Lewis Russia , . 19th September, 1902 London, 2, Winthrop-street, Brady- street, Whitechapel Barnett, Myer . Russia 16th September, 1902 London, 149, Cambridge-road, Mile End Bell, Harris Austria- 24th September, 1902 Durham, 310, Askew-road, West Hungary Gateshead Berg, Edward Russia 5th September, 1902 Sunderland, 26, Peel-street Berg, Herman Russia 5th September, 1902 Sunderland, 13, Foyle-street . Berlinsky, Jacob Russia 15th September, 1902 London, 23, Grey Eagle-street, Spitalfields Berman, William Russia 29th August, 1902 . Dublin, 59, St. Alban's-road, South 1 Circular-road Bischofswerder, Morris. Germany .. 17th September, 1902 Cornwall, 47,Morrab-road, Penzance Bock, David Germany . 27th August, 1902 .. Manchester, 27, Portsmouth-street, Chorlton-upon-Medlock Borsoock, Simon Davis . Russia 16th September, 1902 London, 9, Quaker-street, Spital- fields Brahams, David Russia 24th September. 1902 Norwich, 13, Bank-place Brichta, Marion .. Austria- 15th September,' 1902 Hertfordshire, Eastbury House, Hungary Eastbury, near Watford Bruell (or Brlill), Liidwig Germany . -

Tower Hamlets Local History Library Classification Scheme – 5Th Edition 2021

Tower Hamlets Local History Library and Archives Tower Hamlets Local History Library Classification Scheme 5th Edition | 2021 Tower Hamlets Local History Library Classification Scheme – 5th Edition 2021 Contents 000 Geography and general works ............................................................... 5 Local places, notable passing events, royalty and the borough, world wars 100 Biography ................................................................................................ 7 Local people, collected biographies, lists of names 200 Religion, philosophy and ethics ............................................................ 7 Religious and ethical organisations, places of worship, religious life and education 300 Social sciences ..................................................................................... 11 Racism, women, LGBTQ+ people, politics, housing, employment, crime, customs 400 Ethnic groups, migrants, race relations ............................................. 19 Migration, ethnic groups and communities 500 Science .................................................................................................. 19 Physical geography, archaeology, environment, biology 600 Applied sciences ................................................................................... 19 Public health, medicine, business, shops, inns, markets, industries, manufactures 700 Arts and recreation ............................................................................... 24 Planning, parks, land and estates, fine arts, -

1 MS 290 A1001 Papers of Michael Fidler General Papers 5 Copies Of

1 MS 290 A1001 Papers of Michael Fidler General papers 5 Copies of biographical details, curriculum vitae of Michael 1960, 1966-8 Fidler; correspondence with Who's who; Notes on procedure for the adoption of Conservative candidates in England and Wales (1960); correspondence with Conservative Associations and the Conservative Party Central Office; correspondence relating to recommendations for appointments of magistrates and to the Commission of the Peace in Lancashire 56 Biographical: correspondence with publications; biographical c.1976, 1987-9 details for Who's who, Who's who in Israel, Debrett's, The International Year Book and Statemen's Who's Who, Zionist Year Book, The Jewish Year Book; proofs of entries 4 Newspaper cuttings relating to Michael Fidler; election 1966-7 leaflets 115 Correspondence relating to speaking engagements, the 1974-88 proposed closure of the King David Schools, freemasonry, Leslie Donn and the Honours' List; personal correspondence; letters of appreciation 57 Invitations, 1971-89; text of a sermon by Fidler at the United 1971-89 Reform Church, Bury; text of an address by Fidler to the Council of Manchester and Salford Jews; correspondence with UNICEF, the Liberal Friends of Israel in Australia, the Zionist Organisation of America, and as Director of the Conservative Friends of Israel 63 Jewish Herald: correspondence; text for Fidler's column 1988 `Fidler's forum'; newspaper cuttings 42 Seventieth birthday: table plan of a luncheon; transcripts of 1986 speeches given in Fidler's honour; newspaper cuttings -

Aitken, Berry, Bradford, Bremont, Bull, Hardie, Reid, Stokes, Willis and Collateral Ancestors of Edward D

Aitken, Berry, Bradford, Bremont, Bull, Hardie, Reid, Stokes, Willis and Collateral Ancestors of Edward D. Bradford 2016 This book was first published in 1996 and has been revised during each year since then. This revision is published in 2016 by Edward D. Bradford with copyrights reserved The use for commercial gain of my original work is not permitted The non-commercial use is permitted providing proper credit is given Table Of Contents Introduction 1 Book Organization 2 Preface 3 The Aitken Family 5 The Aitken Family Research 6 Family Group Sheet for William Aitken and Anna Hardie 7 Detains of the William Aitken and Anna Hardie Family 8 Family Group Sheet for Marion Aitken and James Berry 9 Details of the Marion Aitken and James Berry Family 10 The Berry Family 11 The Berry Family Research 12 Family Group Sheet for John Berry 14 Details of the John Berry Family 15 Family Group Sheet for James Berry and Marion Aitken 16 Details of the James Berry and Marion Aitken Family 17 Family Group Sheet for William Berry and Christian Reid 18 Details of the William Berry and Christian Reid Family 19 Family Group Sheet for John Berry and Christian Irvine 20 Details of the John Berry and Christian Irvine Family 21 Outline Descendant Report for James and Ellen Berry 24 Details of the James and Ellen Berry Family 25 Family Group Sheet for John Berry and Mary Ann Poke 26 Details of the John Berry and Mary Ann Poke Family 27 Outline Descendant Report for John James Berry and Emily Harriet Hodge 32 Details of the John James Berry and Emily Harriet Hodge -

London Metropolitan Archives Board of Deputies

LONDON METROPOLITAN ARCHIVES Page 1 BOARD OF DEPUTIES OF BRITISH JEWS ACC/3121 Reference Description Dates BOARD MINUTES Minute books ACC/3121/A/001/A Minute book 1 1760 Nov - Not available for general access Original volume not available for consultation, 1828 Apr Available only with advance please see microfilm copy at English and notice and at the discretion of the ACC/3121/A/001/C Portuguese LMA Director 1 volume Please see microfilm available within archive collection: order ACC/3121/A/001/C ACC/3121/A/001/B Minute book 2 1829 Mar - Unfit Original volume not available for consultation. 1838 Jan Not available for general access Please see microfilm copy at English and Available only with advance ACC/3121/A/001/C Portuguese notice and at the discretion of the 1 volume LMA Director Please see microfilm available within archive collection: order ACC/3121/A/001/C ACC/3121/A/001/C Minutes (on microfilm) 1760-1838 access by written permission only This microfilm contains the first two volumes of English and minutes for the Board covering: Portuguese volume 1: 1760-1828 volume 2: 1829-1838 1 microfilm ACC/3121/A/001/D Minute book 3 1838-1840 access by written permission only 1 volume English and Former Reference: ACC/3121/A/5/3 Portuguese ACC/3121/A/001/E Minute book 4 1840 - 1841 access by written permission only 1 volume Former Reference: ACC/3121/A/5/4 ACC/3121/A/001/F Minute book 5: appendices include some half- 1841-1846 access by written permission only yearly reports, memos and opinions. -

Spitalfields & the East End, a Select Bibliography

A select Spitalfields bibliography This is a brief guide to a selection of items in the Bishopsgate Library about Spitalfields. It is not comprehensive, but aims to give a flavour of the variety of topics surrounding Spitalfields and the different materials available in the library. Books and pamphlets The London Collection contains a total of 45,000+ books and pamphlets about all major aspects of the character of London and its social, economic and architectural development. Useful classification numbers for Spitalfields are: D1 – Immigration D31.4 – Markets, including Spitalfields J – Trades L26.24 – history and geography of the East End including: Stepney, Mile End, Whitechapel, Wapping, Shadwell, St George-in-East, Limehouse, Spitalfields, Norton Folgate. Useful Journals In addition to local history and London-wide journals, the following journals focus particularly on the East End: Cockney Ancestor from 1978 East London History Society Newsletter from 1982 East London Papers 1958–1973 East London Record 1978–1998 Proceedings of the Huguenot Society of London 1885–1995 Rising East 1997–2001 The Cable (Jewish East End Celebration Society) from 2006 Newspaper cuttings and ephemera The Library also collects cuttings from local and national newspapers and magazines and ephemera on the local area. There are files on Spitalfields, Spitalfields Market, the Silk Weavers and individual local streets. Photograph and illustrations The London Photographs Collection contains c.180 photographs of Spitalfields, from 1890 to the present, and c.70 photographs of Spitalfields Market, mainly from 1980s and 1990s. Selected bibliography The next four pages list a selection of items about Spitalfields, its history, development and people. -

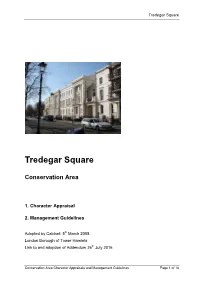

Tredegar Square

Tredegar Square Tredegar Square Conservation Area 1. Character Appraisal 2. Management Guidelines Adopted by Cabinet: 5 th March 2008 London Borough of Tower Hamlets Link to and adoption of Addendum 26 th July 2016 Conservation Area Character Appraisals and Management Guidelines Page 1 of 18 Tredegar Square Introduction Conservation Areas are parts of our local environment with special architectural or historic qualities. They are created by the Council, in consultation with the local community, to preserve and enhance the specific character of these areas for everybody. This guide has been prepared for the following purposes: ° To comply with the Planning (Listed Buildings and Conservation Areas) Act 1990. Section 69(1) states that a conservation area is “an area of special architectural or historic interest, the character or appearance of which it is desirable to preserve or enhance” ° To provide a detailed appraisal of the area’s architectural and historic character. ° To provide an overview of planning policy and propose management guidelines on how this character should be preserved and enhanced in the context of appropriate ongoing change. Conservation Area Character Appraisals and Management Guidelines Page 2 of 18 Tredegar Square Conservation Area Character Appraisals and Management Guidelines Page 3 of 18 Tredegar Square 1. Character Appraisal Overview The Tredegar Square Conservation Area was designated in 1971. The Conservation Area, which encompasses much of Mile End Old Town, is bounded by Lichfield Road and the railway line to the North, Addington Road to the east, Bow Road and Mile End Road to the South and Grove Road to the west. It is an area of special architectural and historic interest, with a character and appearance worthy of protection and enhancement. -

Israel (Includes West Bank and Gaza) 2020 International Religious Freedom Report

ISRAEL (INCLUDES WEST BANK AND GAZA) 2020 INTERNATIONAL RELIGIOUS FREEDOM REPORT Executive Summary The country’s laws and Supreme Court rulings protect the freedoms of conscience, faith, religion, and worship, regardless of an individual’s religious affiliation. The 1992 Basic Law: Human Dignity and Liberty describes the country as a “Jewish and democratic state.” The 2018 Basic Law: Israel – The Nation State of the Jewish People law determines, according to the government, that “the Land of Israel is the historical homeland of the Jewish people; the State of Israel is the nation state of the Jewish People, in which it realizes its natural, cultural, religious and historical right to self-determination; and exercising the right to national self- determination in the State of Israel is unique to the Jewish People.” In June, authorities charged Zion Cohen for carrying out attacks on May 17 on religious institutions in Petah Tikva, Ashdod, Tel Aviv, and Kfar Saba. According to his indictment, Cohen sought to stop religious institutions from providing services to secular individuals, thereby furthering his goal of separating religion and the state. He was awaiting trial at year’s end. In July, the Haifa District Court upheld the 2019 conviction and sentencing for incitement of Raed Salah, head of the prohibited Islamic Movement, for speaking publicly in favor an attack by the group in 2017 that killed two police officers at the Haram al-Sharif/Temple Mount. In his defense, Salah stated that his views were religious opinions rooted in the Quran and that they did not include a direct call to violence. -

Download Catalogue

F i n e Ju d a i C a . pr i n t e d bo o K s , ma n u s C r i p t s , au t o g r a p h Le t t e r s , gr a p h i C & Ce r e m o n i a L ar t K e s t e n b a u m & Co m p a n y We d n e s d a y , ma r C h 21s t , 2012 K e s t e n b a u m & Co m p a n y . Auctioneers of Rare Books, Manuscripts and Fine Art A Lot 275 Catalogue of F i n e Ju d a i C a . PRINTED BOOKS , MANUSCRI P TS , AUTOGRA P H LETTERS , GRA P HIC & CERE M ONIA L ART Featuring: Property from the Library of a New England Scholar ——— To be Offered for Sale by Auction, Wednesday, 21st March, 2012 at 3:00 pm precisely ——— Viewing Beforehand: Sunday, 18th March - 12:00 pm - 6:00 pm Monday, 19th March - 10:00 am - 6:00 pm Tuesday, 20th March - 10:00 am - 6:00 pm No Viewing on the Day of Sale This Sale may be referred to as: “Maymyo” Sale Number Fifty Four Illustrated Catalogues: $38 (US) * $45 (Overseas) KestenbauM & CoMpAny Auctioneers of Rare Books, Manuscripts and Fine Art . 242 West 30th street, 12th Floor, new york, NY 10001 • tel: 212 366-1197 • Fax: 212 366-1368 e-mail: [email protected] • World Wide Web site: www.Kestenbaum.net K e s t e n b a u m & Co m p a n y .