James P. Howley, “The Birth of Newfoundland Archaeology, and the End of History”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Canada Canada De La

c FISHERIES AND MARINE SERVICE SERVICE DES P£CHES ET DES SCIENCES DE LA MER TECHNICAL REPORT No. 691 RAPPORT TECHNIQUE N° 1977 Environment Environnement I Canada Canada Fisheries Service des piches and Marine et des sciences Service de la mer Technical Reports Technical Reports are research documents that are of sufficient importance to be preserved, but which for some reason are not appropriate for primary scientific publication. Inquiries concerning any particular RepOlt should be directed to the issuing establishment. Rapports Techniques Les rapports techniques sont des documents de recherche qui revetent une assez grande importance pour etre conserves mais qui, pour une raison ou pour une autre, ne conviennent pas a une publication scientifique prioritaire. Pour toute demande de renseignements concernant un rapport particulier, i1 faut s'adresser au service responsable. Department of the Environment Ministere de 1'Environnement Fisheries and Marine Service Service des Peches et des Sciences de la mer Research and Development Directorate Direction du Recherche et Developpement • TECHNICAL REPORT No. 691 RAPPORT TECHNIQUE NO. 691 (Numbers 1-456 in this series (Les numeros 1-456 dans cette serie furent were issued as Technical Reports utilises comme Rapports Techniques de 1'office of the Fisheries Research Board of des recherches sur les p~cheries du Canada. Canada. The series name was changed Le nom de la serie fut change avec le with report number 457). rapport numero 457). • Limnology and Fish Populations of Red Indian Lake, a Multi-Use Reservoir by C.J. MORRY and L.J. COLE This is the forty-seventh Ceci est le quarante-septieme Technical Report from the Rapport Technique de la Direction du Research and Development Directorate Recherche et Developpement Newfoundland Biological Station Station biologique de Terre-Neuve St. -

Newfoundland in International Context 1758 – 1895

Newfoundland in International Context 1758 – 1895 An Economic History Reader Collected, Transcribed and Annotated by Christopher Willmore Victoria, British Columbia April 2020 Table of Contents WAYS OF LIFE AND WORK .................................................................................................................. 4 Fog and Foundering (1754) ............................................................................................................................ 4 Hostile Waters (1761) .................................................................................................................................... 4 Imports of Salt (1819) .................................................................................................................................... 5 The Great Fire of St. John’s (1846) ................................................................................................................. 5 Visiting Newfoundland’s Fisheries in 1849 (1849) .......................................................................................... 9 The Newfoundland Seal Hunt (1871) ........................................................................................................... 15 The Inuit Seal Hunt (1889) ........................................................................................................................... 19 The Truck, or Credit, System (1871) ............................................................................................................. 20 The Preparation of -

Notice of Intent to Submit a Claim to Arbitration Under Chapter

NOTICE OF INTENT TO SUBMIT A CLAIM TO ARBITRATION UNDER CHAPTER ELEVEN OF THE NORTH AMERICAN FREE TRADE AGREEMENT ABITIBIBOWATER INC., Investor, v. GOVERNMENT OF CANADA, Party. Pursuant to Articles 1116, 1117, and 1119 of the North American Free Trade Agreement ("NAFTA"), the disputing Investor, AbitibiBowater Inc. (hereinafter "AbitibiBowater" or "the Company"), hereby respectfully serves a Notice ofIntent to Submit a Claim to Arbitration for breach by the Government of Canada (hereinafter "Canada"), through the actions of the provincial Government of Newfoundland and Labrador, of its obligations under Chapter Eleven ofNAFTA. AbitibiBowater also hereby requests Canada and the Government of Newfoundland and Labrador to begin formal consultations and negotiations, as contemplated by NAFTA Article 1118, in an effort to amicabiy resoive this dispute. Such consultations would be in accordance with the Company's proactive outreach to form a joint working group to address and resolve all issues related to its assets and rights in the Province of Newfoundland and Labrador. I. TYPE OF CLAIM 1. AbitibiBowater submits this Notice of Intent both under NAFTA Article 1116 as an investor on its own behalf, and under NAFTA Article 1117 on behalf of three investment enterprises that it owns or controls directly or indirectly: Abitibi-Consolidated Company of Canada, Abitibi-Consolidated Inc. and AbitibiBowater Canada Inc. (hereinafter collectively the "AbitibiBowater Canadian Entities"). II. DISPUTING INVESTOR 2. The disputing investor, AbitibiBowater Inc., is incorporated in the State of Delaware, United States of America, and thus is an enterprise of a Party (the United States) pursuant to NAFTA Article 1139. Its registered address is as follows: 1209 Orange Street Wilmington, Delaware 19801 United States of America Phone: 302-658-7581 Fax: 302-655-2480 III. -

The Hitch-Hiker Is Intended to Provide Information Which Beginning Adult Readers Can Read and Understand

CONTENTS: Foreword Acknowledgements Chapter 1: The Southwestern Corner Chapter 2: The Great Northern Peninsula Chapter 3: Labrador Chapter 4: Deer Lake to Bishop's Falls Chapter 5: Botwood to Twillingate Chapter 6: Glenwood to Gambo Chapter 7: Glovertown to Bonavista Chapter 8: The South Coast Chapter 9: Goobies to Cape St. Mary's to Whitbourne Chapter 10: Trinity-Conception Chapter 11: St. John's and the Eastern Avalon FOREWORD This book was written to give students a closer look at Newfoundland and Labrador. Learning about our own part of the earth can help us get a better understanding of the world at large. Much of the information now available about our province is aimed at young readers and people with at least a high school education. The Hitch-Hiker is intended to provide information which beginning adult readers can read and understand. This work has a special feature we hope readers will appreciate and enjoy. Many of the places written about in this book are seen through the eyes of an adult learner and other fictional characters. These characters were created to help add a touch of reality to the printed page. We hope the characters and the things they learn and talk about also give the reader a better understanding of our province. Above all, we hope this book challenges your curiosity and encourages you to search for more information about our land. Don McDonald Director of Programs and Services Newfoundland and Labrador Literacy Development Council ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I wish to thank the many people who so kindly and eagerly helped me during the production of this book. -

Angler's Guide 2021-2022

Fisheries and Oceans Pêches et Océans Canada Canada Newfoundland and Labrador ANGLER’S GUIDE 2021-2022 www.nfl.dfo-mpo.gc.ca Help us conserve and protect our fish stocks Report illegal fishing activity anonymously to Crime Stoppers 1-800-222-TIPS (8477) OR Report illegal fishing activity directly to Conservation and Protection, Fisheries and Oceans Canada 1-833-DFO-TIPS (336-8477) CATCH-AND-RELEASE ADVICE Practice safe and responsible release techniques to help ensure salmon survival. Follow these procedures to minimize injury to fish: • Barbless hooks must be used. • Do not use a tailer. • When using a landing net, use one with knotless mesh, as it is less harmful to fish scales, gills and eyes. • A leader tip should be heavy enough to bring in large salmon quickly, or light enough to allow large salmon to break off. • Move to a quiet water location. • Bring the fish quickly into reach, or break it off after a couple of runs. • Do not beach the salmon; keep the entire salmon underwater as much as possible. • Handle the salmon gently; do not squeeze the fish and avoid touching the gills and eyes. Loss of scales and damage to the gills caused by pressure on the gills or by removal from the water are the most serious injuries a salmon can suffer. • Remove the hook gently with pliers or with your thumb and forefinger. If the hook must be left in, cut the leader as close to it as possible. • Support the fish under the belly, keeping it in an upright position, underwater and facing into the current. -

Community Files in the Centre for Newfoundland Studies

Community Files in the Centre for Newfoundland Studies A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | J | K | L | M | N | 0 | P | Q-R | S | T | U-V | W | X-Y-Z A Abraham's Cove Adams Cove, Conception Bay Adeytown, Trinity Bay Admiral's Beach Admiral's Cove see Port Kirwan Aguathuna Alexander Bay Allan’s Island Amherst Cove Anchor Point Anderson’s Cove Angel's Cove Antelope Tickle, Labrador Appleton Aquaforte Argentia Arnold's Cove Aspen, Random Island Aspen Cove, Notre Dame Bay Aspey Brook, Random Island Atlantic Provinces Avalon Peninsula Avalon Wilderness Reserve see Wilderness Areas - Avalon Wilderness Reserve Avondale B (top) Baccalieu see V.F. Wilderness Areas - Baccalieu Island Bacon Cove Badger Badger's Quay Baie Verte Baie Verte Peninsula Baine Harbour Bar Haven Barachois Brook Bareneed Barr'd Harbour, Northern Peninsula Barr'd Islands Barrow Harbour Bartlett's Harbour Barton, Trinity Bay Battle Harbour Bauline Bauline East (Southern Shore) Bay Bulls Bay d'Espoir Bay de Verde Bay de Verde Peninsula Bay du Nord see V.F. Wilderness Areas Bay L'Argent Bay of Exploits Bay of Islands Bay Roberts Bay St. George Bayside see Twillingate Baytona The Beaches Beachside Beau Bois Beaumont, Long Island Beaumont Hamel, France Beaver Cove, Gander Bay Beckford, St. Mary's Bay Beer Cove, Great Northern Peninsula Bell Island (to end of 1989) (1990-1995) (1996-1999) (2000-2009) (2010- ) Bellburn's Belle Isle Belleoram Bellevue Benoit's Cove Benoit’s Siding Benton Bett’s Cove, Notre Dame Bay Bide Arm Big Barasway (Cape Shore) Big Barasway (near Burgeo) see -

19 Century Newfoundland Outport Merchants the Jersey Room, Burin

19th century Newfoundland outport merchants The Jersey Room, Burin, c. 1885, S.H. Parsons photo (GPA collection). submitted to Provincial Historic Commemorations Program Dept. Business, Tourism, Culture & Rural Development P.O. Box 8700 St. John's, NL A1E 1J3 submitted by Robert H. Cuff Historian/Writer Gerald Penney Associates Limited PO Box 428, St. John’s, NL A1C 5K4 10 November 2014 Executive Summary In their impact on Newfoundland and Labrador’s economic development, patterns of settlement, and community life, 19th century outport merchants made a significant historic contribution. Their secondary impact, on the Province’s political and cultural development, may be less obvious but was nonetheless vital. Each merchant had a demonstrable impact beyond his home community, in that each supplied nearby communities. Although a merchant’s commercial home sphere was typically in the headquarters bay or region, the majority of the outport merchants were also involved in both fishing and in supplying planters/ fishers in migratory or vessel-based fisheries elsewhere: the Labrador and French Shore fisheries; the seal hunt; and the western boat and Bank fisheries of the south coast. For the purposes of this review it was found helpful to draw a distinction between “resident outport merchants” who lived the full range of their adult lives in rural Newfoundland and the “merchant gentry” whose outport residency was an episode in their business and family life which was otherwise substantially spent in the Old Country or in St. John’s. The resident group may be more worthy of consideration for the Province’s commemoration program. Existing commemorations tend to favour the merchant gentry. -

Stories of the Mi'kmaq

Calvin Coish © 2000, College of the North Atlantic All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form or by any means without the permission of the publisher. Address all inquiries to: College of the North Atlantic P. O. Box 745 Grand Falls-Windsor, NF A2A 2M4 Canadian Cataloguing in Publication Data Coish, E. Calvin Stories of the Mi'kmaq ISBN 0-9682905-7-4 1. Readers for new literates. 2. Micmac indians. I. Coish, E. Calvin II. College of the North Atlantic. PE1127.I5S76 2000 428.6'2 C00-950069-3 Cover Photo: Max Perrier at Heaven Steady, near Lake Ambrose, 1961 Photo Credits: Exploits Indian Band Council (pp. 4, 9, 27, 35, 56) Cora Petrilli (Cover and p. 43 ) Denise Spencer (p. 29) INTRODUCTION "You're about 30 years too late." That's what Jerry Wetzel said when I talked with him about Mi'kmaq history. As Jerry said, many of the old- timers have died in recent years and taken their stories with them. Another of those old-timers, Douglas Paul of Point Leamington died recently. Some of Mr. Paul's memories appear in this book. I wish to offer special thanks to Jerry for his insights into Mi'kmaq and Beothuck history. He is really a wealth of information. Special thanks also to Bernie Hanlon of the Exploits Indian Band Council. Thanks to Howard Bailey, Lou Barker, Cassie Humber, Phil Jeddore, the late Douglas Paul, Nish Paul, Cora Petrilli, Nellie Power, and Denise Spencer. Financial assistance for this project was provided by College of the North Atlantic, National Literacy Secretariat and the Government of Newfoundland and Labrador. -

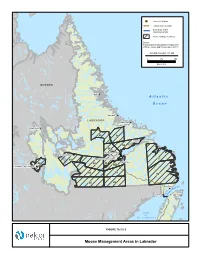

Moose Management Areas in Labrador !

"S Converter Station Transmission Corridor Submarine Cable Crossing Corridor Moose Management Area Source: Newfoundland and Labrador Department of Environment and Conservation (2011) FIGURE ID: HVDC_ST_550 0 75 150 Kilometres QUEBEC Nain ! A t l a n t i c O c e a n Hopedale ! LABRADOR Makkovik ! Postville ! Schefferville! 85 56 Rigolet ! 55 54 North West River ! ! Churchill Falls Sheshatshiu ! Happy Valley-Goose Bay 57 51 ! ! Mud Lake 48 52 53 53A Labrador City / Wabush ! "S 60 59 58 50 49 Red Bay Isle ! elle f B o it a tr Forteau ! S St. Anthony ! G u l f o f St. Lawrence ! Sept-Îles! Portland Creek! Cat Arm FIGURE 10.3.5-2 Twillingate! ! Moose Management Areas in Labrador ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Port Hope Simpson ! Mary's Harbour ! LABRADOR "S Converter Station Red Bay QUEBEC ! Transmission Corridor ± Submarine Cable Crossing Corridor Forteau ! 1 ! Large Game Management Areas St. Anthony 45 National Park 40 Source: Newfoundland and Labrador Department of Environment and Conservation (2011) 39 FIGURE ID: HVDC_ST_551 0 50 100 Kilometres 2 A t l a n t i c 3 O c e a n 14 4 G u l f 41 23 Deer Lake 15 22 o f ! 5 41 ! Gander St. Lawrence ! Grand Falls-Windsor ! 13 42 Corner Brook 7 24 16 21 6 12 27 29 43 17 Clarenville ! 47 28 8 20 11 18 25 29 26 34 9 ! St. John's 19 37 35 10 44 "S 30 Soldiers Pond 31 33 Channel-Port aux Basques ! ! Marystown 32 36 38 FIGURE 10.3.5-3 Moose and Black Bear Management Areas in Newfoundland Labrador‐Island Transmission Link Environmental Impact Statement Chapter 10 Existing Biophysical Environment Moose densities on the Island of Newfoundland are considerably higher than in Labrador, with densities ranging from a low of 0.11 moose/km2 in MMA 19 (1997 survey) to 6.82 moose/km2 in MMA 43 (1999) (Stantec 2010d). -

Micmac, Maliseet, Beothuk Collections Great Britain

Nova Scotia Curatorial Report Number 62 Nova Scotia Museum ~~,.. 1747 Summer Street ....-.~'- Halifax, Nova Scotia,Canada B3H 3A6 Department of Micmac, Education Maliseet, Nova Scotia Museum Complex Beothuk Collections 1n• Great Britain By R. H. Whitehead January 1988 \ f";.( ll~ ·.J r [ ( Curatorial Report Number 62 INVENTORY OF ( MICMAC, MALISEET AND BEOTHUK MATERIAL CULTURE IN INTERNATIONAL COLLECTIONS: GREAT BRITAIN ( ( r r r r r ( r Ruth Holmes Whitehead ( r [ r r NOVA SCO TIA MUSEUM Cu ra toria l Reports The Curatorial Reports of the Nova Scotia Museum con tain information on the collections and the preliminary r esults of research projects carried out under the program of the museum. The reports may be cited in publications but their manuscript status should clearly be indicated. r r r r TABLE OF CONTENTS r GREAT BRITAIN Bath: The American Museum in Great Britain 1 r Bristol: The City Museum and Art Gallery 2 Cambridge: The Scott Polar Research Institute 4 r Cambridge: The University Museum 6 East Cowes: Swiss Cottage Museum, Osborne House 12 r Edinburgh: The Royal Scottish Museum 17 Glasgow: The Hunterian Museum 28 Liverpool: Merseyside County Museum 29 r London: The Bethnal Green Museum 38 London: The Ethnography Department of the British Museum 39 London: The National Maritime Museum at Greenwich 65 r London: The Horniman Museum at Forest Hill 67 London: The Horniman Museum Library 68 London: The Science Museum 69 r 72 Northampton: The Leather Museum Northampton: The Central Museum 73 r Oxford: The Ashmolean Museum 74 Oxford: The Pitt Rivers Museum 77 r Saffron Walden: The Saffron Walden Museum 92 r Truro: The County Museum, Royal Institute of Cornwall 98 r\ r r r. -

The Report of the Electoral Boundaries Commission

.... I. fl I Fm —1 = m an CD 0 CD xi 03 m r m m C) an 0 0 -1 C xi = m C r r xi 0 m 0 -D C C 0 xi C -1 0 C -n r m C,) 0 C Z13 C) C 0 C m 0 -‘ Co Z0 Co C,) - 0 The Report of the 1993 Electoral Boundaries Commission for Newfoundland and Labrador ( Submitted to The Honourable Edward M. Roberts, Q.C. Minister of Justice and Attorney General for the Province ofNewfoundland June, 1994 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE FOREWARD vii Interpretative Notes TERMINOLOGY ix CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION AND OVERVIEW 1 The Constitution of the Commission 1 Acknowledgements 2 The Process of Changing Boundaries 2 Philosophy and Approach to the Task of Redistribution 3 The Name of This Commission 5 CHAPTER 2 THE COMMISSION’S ORIGINAL MANDATE 7 First Meetings of the Commission 7 The Original Mandate of the Commission 7 The Development of the Commission’s First Proposal 9 CHAPTER 3 THE COMMISSION’S 40 SEAT PROPOSAL 11 The 40 SeatProposal 11 Judicial Interpretation - The Commission’s First Proposal and The Saskatchewan Reference Case 14 Page i TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE CHAPTER 4 REACTION TO THE FORTY DISTRICT PROPOSAL 23 General Reaction to the Forty Seat Proposal 23 Regional Reaction to the Commission’s 40 Seat Proposal 26 Reaction From the Labrador Region 26 Reaction From the Great Northern Peninsula 33 Reaction From the Humber Valley (Including White Bay North) and the Baie Verte Peninsula Areas 35 Reaction From the Corner Brook/Bay of Islands Area 37 Reaction From the Stephenville-Port au Port Peninsula-St. -

Red Indian Lake Subregion

ECOREGION Forest Barren Tundra Central Newfoundland Forest Bog Red Indian Lake subregion NF 1 h e C e n t r a l Newfoundland Forest by having the coolest 2 TNewfoundland Forest summers, highest precipitation, and the shortest 2 ecoregion covers about growing season. Despite the cooler average, b 28,000 km2 in the central however, summertime night frosts are not as and northeastern third of common here as in the North-central subregion. 3 t h e i s l a n d o f Although this subregion experiences Newfoundland. The second largest of the Island's higher precipitation — especially when compared nine ecoregions, its forests are the most with the larger North-central subregion to the 4 typically boreal, and its climate is the most north — it is still generally drier than other continental. On average, the highest Island ecoregions. This is due to the summer and lowest winter temperatures ecoregion's location east of the Long Range 5 on the Island occur here. And although Mountains: more rain falls on the mountains' night frosts can occur occasionally western side because winds off the ocean throughout the summer — due to drop their moisture as they climb 6 cold northeast winds off the and cool over the land. L a b r a d o r C u r r e n t — i t Because of the relatively experiences the least wind and dry, warm summers, the Red 7 fog on the Island. I n d i a n L a k e s u b r e g i o n The Red Indian Lake Red Indian Lake experiences a high number of 8 subregion — the second subregion forest fires, as does the rest of largest of the four in the the Central Newfoundland Central Newfoundland Forest Forest.