How to Think About Negotiation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Safeguarding Consumers: Prizes, Promos and Privacy

Washington State Attorney General - Rob McKenna AG Request Legislation – 2009 Session Safeguarding Consumers: Prizes, Promos and Privacy Background: • The Washington Attorney General’s Consumer Protection Division has brought more than a dozen cases involving Internet advertising since 2005 alone. • In April 2007, the Attorney General’s Office reached a settlement with Digital Enterprises of West Hills, doing business as Movieland.com; AccessMedia Networks, of Los Angeles; and Innovative Networks, of Woodland installedHills, that after resolved users allegations signed up theyfor a installedseemingly software anonymous that tookfree trialcontrol for theof a service.consumer’s computer by launching aggressive and persistent pop-ups that demanded payment for a movie download service. The software was concerning allegations that the defendants sold the personal information of thousands of consumers and billed • In June 2007, the office reached a settlement with the Consumer Digital Services, JSE Direct and their subsidiaries consumers for services they did not want. While promoting their Privasafe and SurfSafe products, the defendants advertised that they would “protect your computer and privacy” and guard you from “unscrupulous marketers.” bannerThe Attorney ads and General’s e-mail messages. Office alleged Consumers the defendants submitted lured their Washington personal information consumers withincluding online their offers address, for “free” e-mail gift cards and merchandise including flat-screen monitors; the products were promoted through pop-up ads, Web site address, telephone and birth date, believing they would receive the “free” product. They were subsequently tocharged a tune $14.95 of more charge than $750,000 on their monthly and only phone one Washington bills for defendants’ consumer Internet-related received the advertised service. -

EDUCATION in CHINA a Snapshot This Work Is Published Under the Responsibility of the Secretary-General of the OECD

EDUCATION IN CHINA A Snapshot This work is published under the responsibility of the Secretary-General of the OECD. The opinions expressed and arguments employed herein do not necessarily reflect the official views of OECD member countries. This document and any map included herein are without prejudice to the status of or sovereignty over any territory, to the delimitation of international frontiers and boundaries and to the name of any territory, city or area. Photo credits: Cover: © EQRoy / Shutterstock.com; © iStock.com/iPandastudio; © astudio / Shutterstock.com Inside: © iStock.com/iPandastudio; © li jianbing / Shutterstock.com; © tangxn / Shutterstock.com; © chuyuss / Shutterstock.com; © astudio / Shutterstock.com; © Frame China / Shutterstock.com © OECD 2016 You can copy, download or print OECD content for your own use, and you can include excerpts from OECD publications, databases and multimedia products in your own documents, presentations, blogs, websites and teaching materials, provided that suitable acknowledgement of OECD as source and copyright owner is given. All requests for public or commercial use and translation rights should be submitted to [email protected]. Requests for permission to photocopy portions of this material for public or commercial use shall be addressed directly to the Copyright Clearance Center (CCC) at [email protected] or the Centre français d’exploitation du droit de copie (CFC) at [email protected]. Education in China A SNAPSHOT Foreword In 2015, three economies in China participated in the OECD Programme for International Student Assessment, or PISA, for the first time: Beijing, a municipality, Jiangsu, a province on the eastern coast of the country, and Guangdong, a southern coastal province. -

The Negotiation Process

GW Law Faculty Publications & Other Works Faculty Scholarship 2003 The Negotiation Process Charles B. Craver George Washington University Law School, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.gwu.edu/faculty_publications Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Charles B. Craver, The Negotiation Process, 27 Am. J. Trial Advoc. 271 (2003). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in GW Law Faculty Publications & Other Works by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE NEGOTIATION PROCESS1 By Charles B. Craver2 I. INTRODUCTION Lawyers negotiate constantly. They negotiate on the telephone, in person, through the mail, and through fax and e-mail transmissions, They even negotiate when they do not realize they are negotiating. They negotiate with their own partners, associates, legal assistants, and secretaries; they negotiate with prospective clients and with current clients. They then negotiate on behalf of clients with outside parties as they try to resolve conflicts or structure business arrangements of various kinds. Most attorneys have not formally studied the negotiation process. Few have taken law school courses pertaining to this critical lawyering skill, and most have not read the leading books and articles discussing this topic. Although they regularly employ their bargaining skills, few actually understand the nuances of the bargaining process. When they prepare for bargaining encounters, they devote hours to the factual, legal, economic, and, where relevant, political issues. Most lawyers devote no more than ten to fifteen minutes on their actual negotiation strategy. -

Reasons to Buy: Contaminated Products & Recall Insurance

Casualty Reasons to Buy: Contaminated Products & Recall Insurance Almost any company involved in the food and beverage industry supply chain may be exposed to an accidental contamination and or recall exposure. Also, there is the possibility that a company’s particular brand may be the target of a malicious threat or extortion, either internally or from a third party. The potential financial impact of a product recall, as well as the lasting impact on brand reputation can be of serious concern to a company and its shareholders. AIG Contaminated Products & Recall Insurance not only protects against loss of gross profits and rehabilitation costs following either accidental or malicious contamination, but also provides the crisis management planning and loss prevention services of leading international crisis management specialists in food safety, brand & reputation impacts and extortion. Cover Cover is triggered by the recall of a product caused by: Accidental Contamination Any accidental or unintentional contamination, impairment or mislabeling which occurs during Cover Includes: or as a result of its production, preparation, manufacturing, packaging or distribution; provided • Recall costs that the use or consumption of such product has resulted in or would result in a manifestation of bodily injury, sickness, disease or death of any person within 120 days after consumption or use. • Business interruption (lost gross profit) Malicious Tampering • Rehabilitation costs Any actual, alleged or threatened, intentional, malicious and wrongful alteration or • Consultancy costs contamination of the Insured’s product so as to render it unfit or dangerous for use or consumption or to create such impression to the public, whether caused by employees or not. -

9/11 Report”), July 2, 2004, Pp

Final FM.1pp 7/17/04 5:25 PM Page i THE 9/11 COMMISSION REPORT Final FM.1pp 7/17/04 5:25 PM Page v CONTENTS List of Illustrations and Tables ix Member List xi Staff List xiii–xiv Preface xv 1. “WE HAVE SOME PLANES” 1 1.1 Inside the Four Flights 1 1.2 Improvising a Homeland Defense 14 1.3 National Crisis Management 35 2. THE FOUNDATION OF THE NEW TERRORISM 47 2.1 A Declaration of War 47 2.2 Bin Ladin’s Appeal in the Islamic World 48 2.3 The Rise of Bin Ladin and al Qaeda (1988–1992) 55 2.4 Building an Organization, Declaring War on the United States (1992–1996) 59 2.5 Al Qaeda’s Renewal in Afghanistan (1996–1998) 63 3. COUNTERTERRORISM EVOLVES 71 3.1 From the Old Terrorism to the New: The First World Trade Center Bombing 71 3.2 Adaptation—and Nonadaptation— ...in the Law Enforcement Community 73 3.3 . and in the Federal Aviation Administration 82 3.4 . and in the Intelligence Community 86 v Final FM.1pp 7/17/04 5:25 PM Page vi 3.5 . and in the State Department and the Defense Department 93 3.6 . and in the White House 98 3.7 . and in the Congress 102 4. RESPONSES TO AL QAEDA’S INITIAL ASSAULTS 108 4.1 Before the Bombings in Kenya and Tanzania 108 4.2 Crisis:August 1998 115 4.3 Diplomacy 121 4.4 Covert Action 126 4.5 Searching for Fresh Options 134 5. -

Lab Activity and Assignment #2

Lab Activity and Assignment #2 1 Introduction You just got an internship at Netfliz, a streaming video company. Great! Your first assignment is to create an application that helps the users to get facts about their streaming videos. The company works with TV Series and also Movies. Your app shall display simple dialog boxes and help the user to make the choice of what to see. An example of such navigation is shown below: Path #1: Customer wants to see facts about a movie: >> >> Path #2: Customer wants to see facts about a TV Series: >> >> >> >> Your app shall read the facts about a Movie or a TV Show from text files (in some other course you will learn how to retrieve this information from a database). They are provided at the end of this document. As part of your lab, you should be creating all the classes up to Section 3 (inclusive). As part of your lab you should be creating the main Netfliz App and making sure that your code does as shown in the figures above. The Assignment is due on March 8th. By doing this activity, you should be practicing the concept and application of the following Java OOP concepts Class Fields Class Methods Getter methods Setter methods encapsulation Lists String class Split methods Reading text Files Scanner class toString method Override superclass methods Scanner Class JOptionPane Super-class sub-class Inheritance polymorphism Class Object Class Private methods Public methods FOR loops WHILE Loops Aggregation Constructors Extending Super StringBuilder Variables IF statements User Input And much more.. -

The Union and Journal: Vol. 26, No. 5

BE TRUE, AND FAITHFUL, AND VAJIAHT FOB TES PUBLIC LIBERTIES. VOLUME XXVI. NUMBER 5. Ptmi Rxlw ia tkror of thtta are nerer tue out a I>elieved her to bo ill in her own room— of droMia this houso with tho stain of tho sot out for tho resklcnco of FUmllf pie born-boaster*, awl th«v pet parition advanced toward of (lark Moseley, Squire to the VaJaatioa Commissioner. of the on It. Mm! oat who that dress bo- £|>( (Union aiti journal over it to their dving tlav. I'm one of corner of the kitchen. A wan, wild, hag- Itosanna's mysterious cmplovment Whitgroaro, on route to Bontley Ilall. Artrn. The asemorial and raaoive relatlag to the lata with her door and her gs to. Find ont how tho can 11 muMM mn rmiT mam n tW gard girl, with remarkable beautiftil hair, night-tiuic, looked Cnt person The too footsore to wit Stealer Feaaeadea, mm dova froa the Bcoala account for and king, bring wait, There was one to take hiin. and with a fierce keenness in her candle till the having boon in the room, aad vara ■oeoiMoaoly E. only way eyes, burning morning—Roaan- mounted on an old "with a bp Ihm JKwr. riipud. J. BUTLER, smeared tho between and mill-horse, ae a I appealed U> lib interest in ltachcl and came limping up on a crutch to the table na's suspicious nurchaso of the japanned paint, midnight Oa motion ofMr. Twitcbell, Um Hoaee Kclitor and Proprietor, at me cam Uie two chains from three In tho If the can't old saddle, and a worse bridlo," a mark to the of tlM do. -

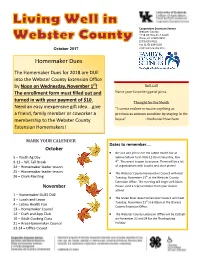

Homemaker Dues

Cooperative Extension Service Webster County 1118 US Hwy 41-A South Dixon, KY 42409-9492 (270) 639-9011 Fax (270) 639-6592 extension.ca.uky.edu October 2017 Homemaker Dues The Homemaker Dues for 2018 are DUE into the Webster County Extension Office by Noon on Wednesday, November 1st! Roll Call The enrollment form must filled out and Name your favorite type of pizza. turned in with your payment of $10. Thought for the Month Need an easy inexpensive gift idea… give “I cannot endure to waste anything as a friend, family member or coworker a precious as autumn sunshine by staying in the membership to the Webster County house” ~Nathaniel Hawthorn Extension Homemakers! MARK YOUR CALENDER Dates to remember…. October Be sure and join us for the Latino health fair at 5 – Youth Ag Day Sebree School from 9:00-12:00 on Saturday, Nov. 9-13 – WC Fall Break 4th. This event is open to anyone. There will be a lot 24 – Homemaker leader lesson of organizations with booths and door prizes! 25 – Homemaker leader lesson The Webster County Homemaker Council will meet 26 – Chalk Painting Tuesday, November 13th at the Webster County Extension Office. The meeting will begin at 9:00am. November Please send a representative from your club to attend. 1 – Homemaker DUES DUE 3 – Lunch and Learn The Green River Area Homemaker Council will meet Tuesday, November 21st at 6:00pm at the Daviess 4 – Latino Health Fair County Extension Office. 13 – Homemaker Council 14 – Craft and App Club The Webster County Extension Office will be CLOSED 16 – Adult Cooking Class on November 23 and 24 for the Thanksgiving 21 – Area Homemaker Council Holiday. -

Negotiating Types of Negotiation

Negotiating What would you do? Alice realizes that this situation with Manuel is similar to negotiations she has faced in other aspects When Alice started recruiting Manuel, she knew of her life. To figure out what to do, she needs to he'd provide the high-profile expertise the determine her best alternative to a negotiated company needed—and she knew he'd be agreement, called a BATNA. Knowing her BATNA expensive. means knowing what she will do or what will But his demands seem to be escalating out of happen if she does not reach agreement in the control. So far, Alice has upped the already-high negotiation at hand. For example, Alice should set salary, added extra vacation time, and increased clear limits on what she's willing to offer Manuel his number of stock options. Now Manuel is and analyze the consequences if she is turned down. asking for an extra performance-based bonus. Would she really be happy choosing a different option for her needs, or is it worth upping the ante to Alice has reviewed the list of other candidates. get exactly what she wants? After she has The closest qualified applicant is very eager for the job, but lacks the experience that Manuel determined her BATNA, she should then figure out would bring. her reservation price, or her "walk-away" number. What's the least favorable point at which she'd Alice prefers Manuel, but she is uncomfortable accept the arrangement with Manuel? Once she with his increasing demands. Should she say knows her BATNA and reservation price, she "no" on principle and risk losing him? Or should should use those as her thresholds in her she agree to his latest request and hope it will be the last? negotiations and not be swayed by Manuel's other demands. -

China's Belt and Road Initiative in the Global Trade, Investment and Finance Landscape

China's Belt and Road Initiative in the Global Trade, Investment and Finance Landscape │ 3 China’s Belt and Road Initiative in the global trade, investment and finance landscape China's Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) development strategy aims to build connectivity and co-operation across six main economic corridors encompassing China and: Mongolia and Russia; Eurasian countries; Central and West Asia; Pakistan; other countries of the Indian sub-continent; and Indochina. Asia needs USD 26 trillion in infrastructure investment to 2030 (Asian Development Bank, 2017), and China can certainly help to provide some of this. Its investments, by building infrastructure, have positive impacts on countries involved. Mutual benefit is a feature of the BRI which will also help to develop markets for China’s products in the long term and to alleviate industrial excess capacity in the short term. The BRI prioritises hardware (infrastructure) and funding first. This report explores and quantifies parts of the BRI strategy, the impact on other BRI-participating economies and some of the implications for OECD countries. It reproduces Chapter 2 from the 2018 edition of the OECD Business and Financial Outlook. 1. Introduction The world has a large infrastructure gap constraining trade, openness and future prosperity. Multilateral development banks (MDBs) are working hard to help close this gap. Most recently China has commenced a major global effort to bolster this trend, a plan known as the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). China and economies that have signed co-operation agreements with China on the BRI (henceforth BRI-participating economies1) have been rising as a share of the world economy. -

The Negotiation Checklist: How to Win the Battle Before It Begins

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by School of Hotel Administration, Cornell University Cornell University School of Hotel Administration The Scholarly Commons Articles and Chapters School of Hotel Administration Collection 2-1997 The Negotiation Checklist: How To Win The Battle Before It Begins Tony L. Simons Cornell University, [email protected] Thomas M. Tripp Washington State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.sha.cornell.edu/articles Part of the Hospitality Administration and Management Commons Recommended Citation Simons, T., & Tripp, T. T. (1997). The negotiation checklist: How to win the battle before it begins. Cornell Hotel and Restaurant Administration Quarterly, 38(1), 14-23. Retrieved [insert date], from Cornell University, School of Hospitality Administration site: http://scholarship.sha.cornell.edu/articles/671/ This Article or Chapter is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Hotel Administration Collection at The Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Articles and Chapters by an authorized administrator of The Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. If you have a disability and are having trouble accessing information on this website or need materials in an alternate format, contact [email protected] for assistance. The Negotiation Checklist: How To Win The Battle Before It Begins Abstract Being well-prepared going into a negotiation is key to being successful when you come out. This negotiation checklist is a tool that can maximize your preparation effectiveness and efficiency. Keywords negotiation, hiring decisions, BATNA Disciplines Hospitality Administration and Management Comments Required Publisher Statement © Cornell University. -

Tales of the Bazaar: Interest-Based Negotiation Across Cultures

In Practice Tales of the Bazaar: Interest-Based Negotiation Across Cultures Jeffrey M. Senger Interest-based negotiation, as popularized by Fisher, Ury, and Patton (1991), is a favored negotiation style of many people in the United States and other parts of the developed world. The author, an American attorney who has traveled widely, assesses how that approach works in different cul- tural contexts. Using illustrations from his own experiences, the author shows how interest-based techniques work successfully, as well as the limi- tations of this approach in some situations. An American traveling abroad can experience negotiation in a vast array of cultures, some of which approach a state of nature. Particularly in devel- oping countries, many people negotiate for just about everything. While the fixed price system of commerce is typical in the U.S. and Western Europe, it simply does not exist in many other parts of the world. Even the simplest things we take for granted, such as a meter in a taxicab, are nowhere to be found, and negotiation is forced into almost every transaction. As a teacher of negotiation, as well as a lifelong student of it, I have found overseas travel to provide an amazing education in the field. Both my background and my current practice center largely on “interest-based negoti- ation” (Fisher, Ury, and Patton, 1991). My formal training is in the legal profession, where I first studied negotiation under Roger Fisher. I now con- duct negotiation and mediation training programs for the U.S. Justice Jeffrey M. Senger is Deputy Senior Counsel for Dispute Resolution for the United States Depart- ment of Justice, 950 Pennsylvania Ave.