Ed 050 477 Pub Dac; Avpilable from Document

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LSD, Ecstasy, "Rave" Parties and the Grateful Dead Someaccountssuggestthatdrugusefacilitatesentrytoan Otherwiseunavailablespirituaworl Ld

The New Psychedelic Culture: LSD, Ecstasy, "Rave" Parties and The Grateful Dead Someaccountssuggestthatdrugusefacilitatesentrytoan otherwiseunavailablespirituaworl ld. by ROBERT B. MILLMAN, MD and RELATIONSHIPOFPSYCHOPATHOLOGYTOPATTERNS ANN BORDWINE BEEDER, MD OFUSE Hallucinogens and psychedelics are terms sychedelics have been used since an- and synthetic compounds primarily derived cient times in diverse cultures as an from indoles and substituted phenethylamines i/ integral part of religious or recrea- usedthat induceto describechangesbothinthethoughtnaturallyor perception.occurring tional ceremony and ritual. The rela- The most frequently used naturally occurring tionship of LSD and other psychedelics to West- substances in this class include mescaline ern culture dates from the development of the from the peyote plant, psilocybin from "magic drug in 1938 by the chemist Albert Hoffman. I mushrooms," and ayuahauscu (yag_), a root LSD and naturally occurring psychedelics such indigenous to South America. The synthetic as mescaline and psilocybin have been associ- drugs most frequently used are MDMA ('Ec- I ated in modem times with a society that re- stasy'), PCP (phencyclidine), and ketamine. jected conventional values and sought transcen- Hundreds of analogs of these compounds are dent meaning and spirituality in the use of known to exist. Some of these obscure com- drugs and the association with other users, pounds have been termed 'designer drugs? During the 1960s the psychedelics were most Perceptual distortions induced by hallu- oi%enused by individuals or small groups on an cinogen use are remarkably variable and de- intermittent basis to _celebrate' an event or to pendent on the influence of set and setting. participate in a quest for spiritual or cultural Time has been described as _standing still" by values, peoplewho spend long periodscontemplating Current use varies from the rare, perhaps perceptual, visual, or auditory stimuli. -

Hip-Hop's Diversity and Misperceptions

The University of Maine DigitalCommons@UMaine Honors College Summer 8-2020 Hip-Hop's Diversity and Misperceptions Andrew Cashman Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/honors Part of the Music Commons, and the Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors College by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. HIP-HOP’S DIVERSITY AND MISPERCEPTIONS by Andrew Cashman A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for a Degree with Honors (Anthropology) The Honors College University of Maine August 2020 Advisory Committee: Joline Blais, Associate Professor of New Media, Advisor Kreg Ettenger, Associate Professor of Anthropology Christine Beitl, Associate Professor of Anthropology Sharon Tisher, Lecturer, School of Economics and Honors Stuart Marrs, Professor of Music 2020 Andrew Cashman All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT The misperception that hip-hop is a single entity that glorifies wealth and the selling of drugs, and promotes misogynistic attitudes towards women, as well as advocating gang violence is one that supports a mainstream perspective towards the marginalized.1 The prevalence of drug dealing and drug use is not a picture of inherent actions of members in the hip-hop community, but a reflection of economic opportunities that those in poverty see as a means towards living well. Some artists may glorify that, but other artists either decry it or offer it as a tragic reality. In hip-hop trends build off of music and music builds off of trends in a cyclical manner. -

Neotrance and the Psychedelic Festival DC

Neotrance and the Psychedelic Festival GRAHAM ST JOHN UNIVERSITY OF REGINA, UNIVERSITY OF QUEENSLAND Abstract !is article explores the religio-spiritual characteristics of psytrance (psychedelic trance), attending speci"cally to the characteristics of what I call neotrance apparent within the contemporary trance event, the countercultural inheritance of the “tribal” psytrance festival, and the dramatizing of participants’ “ultimate concerns” within the festival framework. An exploration of the psychedelic festival offers insights on ecstatic (self- transcendent), performative (self-expressive) and re!exive (conscious alternative) trajectories within psytrance music culture. I address this dynamic with reference to Portugal’s Boom Festival. Keywords psytrance, neotrance, psychedelic festival, trance states, religion, new spirituality, liminality, neotribe Figure 1: Main Floor, Boom Festival 2008, Portugal – Photo by jakob kolar www.jacomedia.net As electronic dance music cultures (EDMCs) flourish in the global present, their relig- ious and/or spiritual character have become common subjects of exploration for scholars of religion, music and culture.1 This article addresses the religio-spiritual Dancecult: Journal of Electronic Dance Music Culture 1(1) 2009, 35-64 + Dancecult ISSN 1947-5403 ©2009 Dancecult http://www.dancecult.net/ DC Journal of Electronic Dance Music Culture – DOI 10.12801/1947-5403.2009.01.01.03 + D DC –C 36 Dancecult: Journal of Electronic Dance Music Culture • vol 1 no 1 characteristics of psytrance (psychedelic trance), attending specifically to the charac- teristics of the contemporary trance event which I call neotrance, the countercultural inheritance of the “tribal” psytrance festival, and the dramatizing of participants’ “ul- timate concerns” within the framework of the “visionary” music festival. -

Hands up Classics Pulsedriver Hands up Magazine Anniversary Edition

HUMAG 12 Hands up Magazine anniversary Edition hANDS Up cLASSICS Pulsedriver Page 1 Welcome, The time has finally come, the 12th edition of the magazine has appeared, it took a long time and a lot has happened, but it is done. There are again specials, including an article about pulsedriver, three pages on which you can read everything that has changed at HUMAG over time and how the de- sign has changed, one page about one of the biggest hands up fans, namely Gabriel Chai from Singapo- re, who also works as a DJ, an exclusive interview with Nick Unique and at the locations an article about Der Gelber Elefant discotheque in Mühlheim an der Ruhr. For the first time, this magazine is also available for download in English from our website for our friends from Poland and Singapore and from many other countries. We keep our fingers crossed Richard Gollnik that the events will continue in 2021 and hopefully [email protected] the Easter Rave and the TechnoBase birthday will take place. Since I was really getting started again professionally and was also ill, there were unfortu- nately long delays in the publication of the magazi- ne. I apologize for this. I wish you happy reading, Have a nice Christmas and a happy new year. Your Richard Gollnik Something Christmas by Marious The new Song Christmas Time by Mariousis now available on all download portals Page 2 content Crossword puzzle What is hands up? A crossword puzzle about the An explanation from Hands hands up scene with the chan- Up. -

Electronic Dance Music

Electronic Dance Music Spring 2016 / Tuesdays 6:00 pm – 9:50 pm Taper Hall of the Humanities, 202 MUSC 410, 4.0 Units Instructor: Dr. Sean Nye Email: [email protected] Office Hours: Tuesdays, 3–5 p.m. in 305 MUS Description: In this decade, Electronic Dance Music (EDM) has experienced an extraordinary renaissance in the United States, both in terms of music and festival culture. This development has not only surprised and fascinated the popular press, but also long-established EDM scholars and protagonists. Some have gone so far as to claim that EDM is the music of the Millennial Generation. Beyond these current developments, EDM’s history – as disco, house, techno, rave, electronica, etc. – spans a broader chronology from the 1970s to the present. It involves multiple intersections with the music and cultures of hip-hop and reggae, among others. In this course, we will examine EDM through a dual perspective emerging from our present moment: (1) the history of global EDM, especially in Europe and the United States, between the 1970s and the 2000s, and (2) current EDM scenes in Los Angeles and beyond. To address this perspective, we will carefully read from Simon Reynolds’s classic history of rave culture, Energy Flash: A Journey Through Rave Music and Dance Culture. Additional readings will include selections from a newly published history of American EDM, Michaelangelo Matos’s The Underground is Massive: How Electronic Dance Music Conquered America. We will also have guest speakers to discuss a range of EDM cultural practices and issues. Objectives: As a course open to non-music majors, this class will attempt to enrich our experiences and critical engagement with EDM. -

Thehard DATA Summer 2015 A.D

FFREE.REE. TheHARD DATA Summer 2015 A.D. EEDCDC LLASAS VEGASVEGAS BASSCONBASSCON & AAMERICANMERICAN GGABBERFESTABBERFEST REPORTSREPORTS NNOIZEOIZE SUPPRESSORSUPPRESSOR INTERVIEWINTERVIEW TTHEHE VISUALVISUAL ARTART OFOF TRAUMA!TRAUMA! DDARKMATTERARKMATTER 1414 YEARYEAR BASHBASH hhttp://theharddata.comttp://theharddata.com HARDSTYLE & HARDCORE TRACK REVIEWS, EVENT CALENDAR1 & MORE! EDITORIAL Contents Tales of Distro... page 3 Last issue’s feature on Los Angeles Hardcore American Gabberfest 2015 Report... page 4 stirred a lot of feelings, good and bad. Th ere were several reasons for hardcore’s comatose period Basscon Wasteland Report...page 5 which were out of the scene’s control. But two DigiTrack Reviews... page 6 factors stood out to me that were in its control, Noize Suppressor Interview... page 8 “elitism” and “moshing.” Th e Visual Art of Trauma... page 9 Some hardcore afi cionados in the 1990’s Q&A w/ CIK, CAP, YOKE1... page 10 would denounce things as “not hardcore enough,” Darkmatter 14 Years... page 12 “soft ,” etc. Th is sort of elitism was 100% anti- thetical to the rave idea that generated hardcore. Event Calendar... page 15 Hardcore and its sub-genres were born from the PHOTO CREDITS rave. Hardcore was made by combining several Cover, pages 5,8,11,12: Joel Bevacqua music scenes and genres. Unfortunately, a few Pages 4, 14, 15: Austin Jimenez hardcore heads forgot (or didn’t know) they came Page 9: Sid Zuber from a tradition of acceptance and unity. Granted, other scenes disrespected hardcore, but two The THD DISTRO TEAM wrongs don’t make a right. It messes up the scene Distro Co-ordinator: D.Bene for everyone and creativity and fun are the fi rst Arcid - Archon - Brandon Adams - Cap - Colby X. -

Thehard DATA Spring 2015 A.D

Price: FREE! Also free from fakes, fl akes, and snakes. TheHARD DATA Spring 2015 A.D. Watch out EDM, L.A. HARDCORE is back! Track Reviews, Event Calendar, Knowledge Bombs, Bombast and More! Hardstyle, Breakcore, Shamancore, Speedcore, & other HARD EDM Info inside! http://theharddata.com EDITORIAL Contents Editorial...page 2 Welcome to the fi rst issue of Th e Hard Data! Why did we decided to print something Watch Out EDM, this day and age? Well… because it’s hard! You can hold it in your freaking hand for kick drum’s L.A. Hardcore is Back!... page 4 sake! Th ere’s just something about a ‘zine that I always liked, and always will. It captures a point DigiTrack Reviews... page 6 in time. Th is little ‘zine you hold in your hands is a map to our future, and one day will be a record Photo Credits... page 14 of our past. Also, it calls attention to an important question of our age: Should we adapt to tech- Event Calendar... page 15 nology or should technology adapt to us? Here, we’re using technology to achieve a fun little THD Distributors... page 15 ‘zine you can fold back the page, kick back and chill with. Th e Hard Data Volume 1, issue 1 For a myriad of reasons, periodicals about Publisher, Editor, Layout: Joel Bevacqua hardcore techno have been sporadic at best, a.ka. DJ Deadly Buda despite their success (go fi gure that!) Th is has led Copy Editing: Colby X. Newton to a real dearth of info for fans and the loss of a Writers: Joel Bevacqua, Colby X. -

Rave-Culture-And-Thatcherism-Sam

Altered Perspectives: UK Rave Culture, Thatcherite Hegemony and the BBC Sam Bradpiece, University of Bristol Image 1: Boys Own Magazine (London), Spring 1988 1 Contents Introduction……………………………………………………………………………………………………...……… 7 Chapter 1. The Rave as a Counter-Hegemonic Force: The Spatial Element…….…………….13 Chapter 2. The Rave as a Counter Hegemonic Force: Confirmation and Critique..…..…… 20 Chapter 3. The BBC and the Rave: An Agent of Moral Panic……………………………………..… 29 Conclusion…………………………………………………………………………………………………………….... 37 Appendices…………………………………………………………………………………………………………...... 39 Bibliography………………………………………………………………………………………………………...... 50 2 ‘You cannot break it! The bonding between the ravers is too strong! The police and councils will never tear us apart.’ In-ter-dance Magazine1 1 ‘Letters’, In-Ter-Dance (Worthing), Jul. 1993. 3 Introduction Rave culture arrived in Britain in the late 1980s, almost a decade into the premiership of Margaret Thatcher, and reached its zenith in the mid 1990s. Although academics contest the definition of the term 'rave’, Sheila Henderson’s characterization encapsulates the basic formula. She describes raves as having ‘larger than average venues’, ‘music with 120 beats per minute or more’, ‘ubiquitous drug use’, ‘distinctive dress codes’ and ‘extensive special effects’.2 Another significant ‘defining’ feature of the rave subculture was widespread consumption of the drug methylenedioxyphenethylamine (MDMA), otherwise known as Ecstasy.3 In 1996, the government suggested that over one million Ecstasy tablets were consumed every week.4 Nicholas Saunders claims that at the peak of the drug’s popularity, 10% of 16-25 year olds regularly consumed Ecstasy.5 The mass media has been instrumental in shaping popular understanding of this recent phenomenon. The ideological dominance of Thatcherism, in the 1980s and early 1990s, was reflected in the one-sided discourse presented by the British mass media. -

Rave Reviews

AUG 2019 ALL Keto + Paleo Tues Twofer Tuesday - of Features AuG Dinner for Two 4PM - 10PM 4PM - 10PM Keto Sliders - $10.00 Enjoy this Tuesday deal with a dinner for two Sesame seed crusted beef slider, griddle-seared and for just $25! Price includes an appetizer, served on leaf lettuce. Topped with your choice of two entrées and a delicious dessert. cheese, spicy pickles, and a secret sauce. Served with your choice of one side. TWOFER MENU - $25.00 Keto Wrap - $11.00 Pick One Shareable Starter A leaf lettuce wrap filled with grilled chicken, bacon, • Chicken Bites with Your Choice of Sauce guacamole, and Southwest Ranch. • Calamari Strips with Spicy Ketchup Served with your choice of one side. • Cheese Sticks with Marinara Sauce • Loaded French Fries • Fried Jalapeños • Two Side Salads Paleo Sliders - $12.00 Seared sweet potato discs topped with a beef patty, Pick Two Entrées guacamole, and bacon. • Slider Trio with Your Choice of Side Served with your choice of one side. • Chicken Wings with Your Choice of Side • BBQ Bacon Burger with Your Choice of Side • Grilled Cheese Pasta with Your Choice of Side Paleo Personal Pizza - $11.00 • Ranch Chicken with Your Choice of Side Almond flour crust, topped with house pizza sauce, • Firecracker Alligator with Your Choice of Side vegan cheese, mushrooms, onions, peppers, • Shrimp Trio with Your Choice of Side and black olives. Pick Two Dessert Bites • Fried Strawberry with Berry Puree Side Selections - $3.00 • Mint Chocolate Chip Ice Cream with Strawberry Garlic Roasted Cauliflower Rumchata Sauce Grilled Zucchini • Chef’s Weekly Dessert Feature Grilled Portabella Cap Bacon Guacamole + $1.00 Rave Reviews BAR FEATURES $2.00 - White Claws “Excellent American cuisine, service is always $2.00 - Michelob Ultras above par and the overall atmosphere $5.00 - Keto Pomegranate Peach Bellini in the restaurant is awesome.” $5.00 - Keto Bloody Mary -Hudson, Google Review Located in Holiday Inn & Suites - 7601 N. -

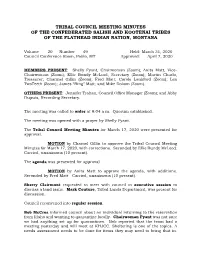

033120 Minutes.Pdf

TRIBAL COUNCIL MEETING MINUTES OF THE CONFEDERATED SALISH AND KOOTENAI TRIBES OF THE FLATHEAD INDIAN NATION, MONTANA Volume 20 Number 49 Held: March 31, 2020 Council Conference Room, Pablo, MT Approved: April 7, 2020 MEMBERS PRESENT: Shelly Fyant, Chairwoman (Zoom); Anita Matt, Vice- Chairwoman (Zoom); Ellie Bundy McLeod, Secretary (Zoom); Martin Charlo, Treasurer; Charmel Gillin (Zoom); Fred Matt; Carole Lankford (Zoom); Len TwoTeeth (Zoom); James “Bing” Matt; and Mike Dolson (Zoom). OTHERS PRESENT: Jennifer Trahan, Council Office Manager (Zoom); and Abby Dupuis, Recording Secretary. The meeting was called to order at 9:04 a.m. Quorum established. The meeting was opened with a prayer by Shelly Fyant. The Tribal Council Meeting Minutes for March 17, 2020 were presented for approval. MOTION by Charnel Gillin to approve the Tribal Council Meeting Minutes for March 17, 2020, with corrections. Seconded by Ellie Bundy McLeod. Carried, unanimous (10 present). The agenda was presented for approval. MOTION by Anita Matt to approve the agenda, with additions. Seconded by Fred Matt. Carried, unanimous (10 present). Sherry Clairmont requested to meet with council in executive session to discuss a land issue. Mark Couture, Tribal Lands Department, was present for discussion. Council reconvened into regular session. Bob McCrea informed council about an individual returning to the reservation from Idaho and wanting to quarantine locally. Chairwoman Fyant was not sure we had anything set up for quarantines. Bob reported that the team had a meeting yesterday and will meet at KHJCC. Sheltering is one of the topics. A needs assessment needs to be done for items they may need to bring that in. -

![[2FY3]⋙ Generation Ecstasy: Into the World of Techno and Rave Culture by Simon Reynolds #MCXU81FLSGA #Free Read Online](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4330/2fy3-generation-ecstasy-into-the-world-of-techno-and-rave-culture-by-simon-reynolds-mcxu81flsga-free-read-online-2034330.webp)

[2FY3]⋙ Generation Ecstasy: Into the World of Techno and Rave Culture by Simon Reynolds #MCXU81FLSGA #Free Read Online

Generation Ecstasy: Into the World of Techno and Rave Culture Simon Reynolds Click here if your download doesn"t start automatically Generation Ecstasy: Into the World of Techno and Rave Culture Simon Reynolds Generation Ecstasy: Into the World of Techno and Rave Culture Simon Reynolds In Generation Ecstasy, Simon Reynolds takes the reader on a guided tour of this end-of-the-millenium phenomenon, telling the story of rave culture and techno music as an insider who has dosed up and blissed out. A celebration of rave's quest for the perfect beat definitive chronicle of rave culture and electronic dance music. Download Generation Ecstasy: Into the World of Techno and R ...pdf Read Online Generation Ecstasy: Into the World of Techno and ...pdf Download and Read Free Online Generation Ecstasy: Into the World of Techno and Rave Culture Simon Reynolds From reader reviews: Linda Callaway: Now a day individuals who Living in the era everywhere everything reachable by connect to the internet and the resources within it can be true or not call for people to be aware of each data they get. How a lot more to be smart in having any information nowadays? Of course the solution is reading a book. Reading a book can help folks out of this uncertainty Information especially this Generation Ecstasy: Into the World of Techno and Rave Culture book because book offers you rich data and knowledge. Of course the knowledge in this book hundred % guarantees there is no doubt in it you probably know this. Steven Richardson: Information is provisions for anyone to get better life, information currently can get by anyone with everywhere. -

Essays on Land and Scouting

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 2017 GROUND FIRES: Essays on Land and Scouting Matthew R. Hart University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Part of the Nonfiction Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Hart, Matthew R., "GROUND FIRES: Essays on Land and Scouting" (2017). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 10994. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/10994 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. GROUND FIRES: Essays on Land and Scouting By MATTHEW ROBERT HART BA, Carleton College, Northfield, MN, 2011 Thesis presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Environmental Studies The University of Montana Missoula, MT May 2017 Approved by: Scott Whittenburg, Dean of The Graduate School Graduate School Phil Condon, Chair Environmental Studies Dan Spencer Environmental Studies Judy Blunt English Hart, Matthew, MS, Spring 2017 Environmental Studies Ground Fires: Essays on Land and Scouting Chairperson: Phil Condon Abstract: Ground Fires is a collection of creative nonfiction probing the social and environmental complexities that marked the narrator’s long membership in the Boy Scouts of America. I grew up a Scout, part of a quirky, adventurous troop in a New England college town.