Church of the Disciples

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Arlington Street Church! Unitarian Universalist Wednesday Gatheringarlington Street Church, Unitarian Universalist Thank You

Lama Surya Das Young Adult Group Wednesday, September 16th, 7:30 PM – 9:15 PM, Hunnewell Chapel The Young Adult Group (ages 18–35) meets two Fridays per $15 (proceeds will be shared with the church) month at 7 pm in the Perkins Room (downstairs next to the Please join Rev. Kim in welcoming to Arlington Street her beloved kitchen) for activities, food, and worship. The schedule of and esteemed friend, Lama Surya Das. Surya will be with us on the meetings can be found on Arlington Street Church’s online third Wednesday evenings of each month, beginning this week! calendar at www.ASCBoston.org. NEWS FROM THE SOUL OF SUNDAY Lama Surya Das is one of the foremost Western Buddhist meditation The Young Adult Group also meets for lunch after the service teachers and scholars, one of the main interpreters of Tibetan on Sundays. You can purchase food from the Sandwich Board Sunday, September 13t h , 20 0 9 Buddhism in the West, and a leading spokesperson for the emerging during Coffee Hour, or bring your own food. The group meets American Buddhism. The Dalai Lama calls him “The Western Lama.” in the Stage Right Room. The Stage Right Room is the first Surya has spent thirty-five years studying Buddhism with the great room on your left after going down the stairs at the back of the Today’s Events masters of Asia, including the Dalai Lama’s own teachers, and has sanctuary. The group will begin their informal lunches shortly – please check the church calendar for details. -

Meeting House News

MEETING HOUSE NEWS Table of Contents Sundays at First Parish 3 Worship-at-a-Glance 3 Celebrate Rev. Jo VonRue 3 Summer Services 3 Sunday Forums 4 Homecoming Picnic 4 Café Off for the Summer 4 Pastoral Care 5 Ministers 5 Come to Cook 5 Sacred Texts of the World 5 First Parish Rides 6 MUUsings 6 By Your Side Singers 7 Minister in Residence 7 Photo by Sara Ballard. Church steeple framed by the Adult Education 8 Valerie Holt memorial dogwood. Mens Spirituality Retreat 8 Youth Group 8 Religious Exploration (RE) News 8 RE Field Day 9 Ice-Cream Social 9 Summer Program for Kids 9 Introducing Wendy Dalton 10 SAVE THE DATES Sign-Ups 10 Annual Meeting, June 10 Standing Committee News 11 General Assembly, June 20-24 Arts at First Parish 13 Upcoming Events 14 June 2018 Page 1 of 27 Meeting House News Social Action Community 14 Amnesty International, Group 15 14 Celebrate Community Dinner 14 Environmental Leadership Team 15 Pride Service and Parade 15 Transylvanian Pilgrimage a Success! 15 Womens News 16 AWE Upcoming Events 16 Womens Parish Association 17 Herb Garden Coffee Hour Party 17 Visit Our Gardens 18 Other Cool Stuff 18 Concord Area Humanists 18 First Tuesday Group 19 FP Flowers on YouTube 19 General Assembly 2018 20 Website Wonder 20 Herb garden photo by Doug Baker including the Listening to Past Sermons 20 armillary sundial . Communications at First Parish 21 First Parish General Information 23 Summer Services 25 Summer office hours begin June 19. Annual Meeting Vote 26 Tuesday Friday, 9:00 a.m. -

Our History Tracing Our Congregation from 1729 to Today

Our History Tracing our Congregation from 1729 to Today ARLINGTON STREET CHURCH Unitarian Universalist Beginnings • Our community began as a group of Scots-Irish Calvinists gathered in a converted barn on Long Lane in Boston on November 15th, 1729. The inhospitable residents of Boston dubbed them derogatorily as “The Church of the Presbyterian Strangers,” and the name stuck. The building be- came known as the Long Lane Meeting House. • A real church was built on the site in 1744; in it, the Massachusetts State Convention met and ratified the Constitution of the United States on February 7th, 1788. When the street name was changed from Long Lane to Federal Street in honor of the event, the building became known as The Federal Street Church • In 1787, the congregation, wanting to be self- governing, voted to call Jeremy Belknap, a liberal Congregationalist, to lead them in adopting the congregational form of governance. Thus they left the required creed and rule of the Presbytery. • William Ellery Channing, often known as the Fa- ther of GatheredAmerican Unitarianism, served as Senior Minister at the Federal Street Church from 1803 to 1842. Under his leadership the congregation prospered. To accommodate the crowds that Channing drew, the thirdin meeting house, Lovede- and Service signed by the noted Charles Bulfinch, was built in 1809 on the Federal Street site. • In 1819 Channing delivered “The Baltimore Sermon,” which defined the new Unitarianfor the- Justice and Peace ology for the burgeoning Unitarian movement. Although Channing originally resisted formation of a new denomination, under the direction of his associate and later successor, Ezra Stiles Gan- nett, the move toward separation from the Con- gregationalists began. -

Residences on Morrissey Boulevard, 25 Morrissey Boulevard, Dorchester

NOTICE OF INTENT (NOI) TEMPORARY CONSTRUCTION DEWATERING RESIDENCES AT MORRISSEY BOULEVARD 25 MORRISSEY BOULEVARD DORCHESTER, MASSACHUSETTS by Haley & Aldrich, Inc. Boston, Massachusetts on behalf of Qianlong Criterion Ventures LLC Waltham, Massachusetts for US Environmental Protection Agency Boston, Massachusetts File No. 40414-042 July 2014 Haley & Aldrich, Inc. 465 Medford St. Suite 2200 Boston, MA 02129 Tel: 617.886.7400 Fax: 617.886.7600 HaleyAldrich.com 22 July 2014 File No. 40414-042 US Environmental Protection Agency 5 Post Office Square, Suite 100 Mail Code OEP06-4 Boston, Massachusetts 02109-3912 Attention: Ms. Shelly Puleo Subject: Notice of Intent (NOI) Temporary Construction Dewatering 25 Morrissey Boulevard Dorchester, Massachusetts Dear Ms. Puleo: On behalf of our client, Qianlong Criterion Ventures LLC (Qianlong Criterion), and in accordance with the National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NPDES) Remediation General Permit (RGP) in Massachusetts, MAG910000, this letter submits a Notice of Intent (NOI) and the applicable documentation as required by the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) for temporary construction site dewatering under the RGP. Temporary dewatering is planned in support of the construction of the proposed Residences at Morrissey Boulevard in Dorchester, Massachusetts, as shown on Figure 1, Project Locus. We anticipate construction dewatering will be conducted, as necessary, during below grade excavation and planned construction. The site is bounded to the north by the JFK/UMass MBTA red line station, to the east by William T. Morrissey Boulevard, to the south by paved parking associated with Shaw’s Supermarket, beyond which lies the Shaw’s Supermarket, and to the west by MBTA railroad tracks and the elevated I-93 (Southeast Expressway). -

UUMA 2015 Annual Review UUMA Annual Review Year of 2015 from the UUMA Board of Trustees

UUMA 2015 Annual Review UUMA Annual Review Year of 2015 From the UUMA Board of Trustees The UUMA Board has had an exciting and creative year. Some might wonder what the Board actually does to benefit our Contents members, since we have delegated the programmatic work of fulfilling the mission of “nurturing excellence in ministry through Board of Trustees Report ..... 2 collegiality, continuing education and collaboration” to our Staff Report .......................... 4 awesome Executive Director and staff and many great program teams of volunteers. We have left to ourselves this work: 50-Year Sermon ................... 6 To set the vision for the UUMA. 25-Year Sermon .................. 10 To monitor the UUMA’s progress towards achieving its Berry Street Essay .............. 13 vision. Obituaries ........................... 25 To stay in touch with and listen to our members. UUMA CENTER News ...... 46 To keep learning more about being a great Board. To be collaborative leaders and trustworthy stewards of Endowment Honorees ...... 50 our resources (people, money, history). To keep ourselves accountable to do our work well. Reviewing the year 2015, there’s a lot of ground we covered. Among the many things we accomplished, a few highlights season to season included: Winter: Participating at the Institute in Asilomar Collegial conversation around our “Big Question” about what we need to be thinking of as we frame new Visions. Connecting with Stewardship “Ambassadors.” March: Attending 50th anniversary events in Selma and Birmingham. Learning from Beth Zemsky, helping us see more clearly how to do all our work incorporating learnings of inter-cultural competency. Accomplished a major self-evaluation of how we the Board are functioning. -

UUSA Annual Report from the Board

THE UNITARIAN UNIVERSALIST SOCIETY OF AMHERST A Welcoming Congregation A Green Sanctuary Congregation ANNUAL REPORT May 2019 PO Box 502, 121 North Pleasant Street, Amherst MA 01004-0502 [email protected] www.uusocietyamherst.org Tel. 413-253-2848 The Reverend Stephen Cook, Interim Minister THE UNITARIAN UNIVERSALIST SOCIETY OF AMHERST A Welcoming Congregation A Green Sanctuary Congregation ANNUAL REPORT May 2019 Table of Contents Board of Trustees ................................................................................................... Page 3 Interim Minister ..................................................................................................... Page 5 Pledge Drive Task Force ........................................................................................ Page 6 Caring Circle .......................................................................................................... Page 9 Dedicated Offering Committee ............................................................................ Page 10 Digital Outreach Committee ................................................................................ Page 11 Dismantling White Supremacy Task Force ......................................................... Page 12 Finance Committee .............................................................................................. Page 13 Fundraising Committee ........................................................................................ Page 15 Green Sanctuary Committee ............................................................................... -

And Guide to Massachusetts State Legislative Documents, 1802-1882

^A^^ sH.3'-:ro Y^ COMMONWEALTH OF MASSACHUSETTS MSSACHUSETTS ^ INDEX AND GUIDE TO \ STATE LEGISLATIVE DOCUMENTS 1^02-1882 Compiled by Francis X. Blouin Jr. Massachusetts State Library- George Fingold Library- State House, Boston 1972 MASSACHUSETTS STATE LEGISLATIVE DOCUMENTS l802-iaS2 During the nineteenth century, the Commonwealth of Massa- chusetts experienced an almost complete transformation. The changes which took place during those years touched all aspects of life and segments of society within the state. The popiolation, continually increasing, became in many ways diversified. The mobility of existing population and immigra- tion produced numerous changes in the political, social and intellectual life of the state. Once dependent on agriculture and shipping, the state by 1880 was one of the most industrial- ized in the nation. The nineteenth century population experienced rapid urbanization as nximerous new cities and towns arose throughout the state and population increased in those already in existence. By the l880*s the state seemed much smaller as canals and especially the railroad provided a transportation network which latticed the entire state. One of the more active participants in this process of change was the IVIass, General Court. Though perhaps as much an observer as participant, the General Court , through consider- ation of various petitions and reports placed before it, left behind a mound of legislative documents regarding various as- pects of political, economic, and social life in 19th century Massachusetts, In all more than 15,000 separate pieces of legislation were considered during the years 1802-1882, Most of these dociiments have remained lost between the covers of the enormous volvimes in which the bills and reports are bound. -

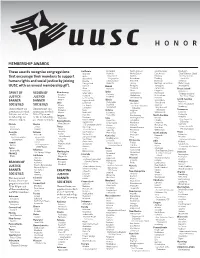

H O N O R C O

HONOR CONGREGATIONS OF 2007* MEMBERSHIP AWARDS CONGREGATIONAL CORPORATE GIVING AWARDS These awards recognize congregations California Brunswick North Andover Central Square Pittsburgh Oregon Anaheim Marietta North Easton East Aurora First Unitarian Church These gifts institutionalize a congrega- Bend that encourage their members to support Aptos Emerson UU Norton Fredonia UU Church of the tion’s deep commitment to justice and Hillsboro Bakersfield Congregation Petersham Flushing South Hills Oregon City human rights and social justice by joining Bayside Sandy Springs Pittsfield Hamburg Smithton human rights through the work of UUSC. Tennessee Canoga Park Valdosta Quincy Hastings-on-Hudson State College Cookeville UUSC with an annual membership gift. Carmel Hawaii Rockport Jamesport Stroudsburg Tullahoma Chico Honolulu Sherborn Jamestown Rhode Island Santa Barbara Sharon Fremont Stow Kingston HELEN FOGG Texas Idaho Providence Studio City Sherborn Austin New Jersey Grass Valley Swampscott Manhasset SPIRIT OF VISION OF Kimberly Religious Society of CHALICE Sudbury Paramus Hayward Watertown Muttontown Colorado First UU Church Pocatello Bell Street Chapel Swampscott College Station JUSTICE JUSTICE Pomona La Crescenta West Roxbury Pomona SOCIETY Golden South Carolina Watertown Fort Worth Wayne Laguna Beach Illinois Queensbury Lafayette BANNER BANNER Michigan Beaufort Wayland Ohio Livermore Carbondale Stony Brook Honors congrega- Connecticut Westside UU Church Ann Arbor Hilton Head Island Wellesley Hills Houston SOCIETIES SOCIETIES Athens Los -

Meeting House News September 2006 Along the Way Anita Farber-Robertson Your Leadership Is Strong and Devoted

The First Parish in Cambridge, The First Church, Unitarian-Universalist Meeting House News September 2006 Along the Way Anita Farber-Robertson Your leadership is strong and devoted. A new moon Your congregation is diverse and welcoming to teaches gradualness many. Your presence in the community speaks and deliberation and of your commitment to responsibility as well how one gives birth as freedom, to a faith that is compassionate to oneself slowly. and at times courageous. I do not expect Patience with small those essential attributes to change - although details makes perfect over time you may find new ways in which to a large work, like the express them. universe. As we gather ourselves in, armloads of us - Rumi like pumpkins at the harvest, let us take the With those time to breathe and be, reveling in the presence words of Rumi in of one another. Let us take the lessons of the my mind, and his wisdom in my soul, I greet moon to heart, and grant ourselves the luxury you. With joy, hope and anticipation I open of time to settle in to our new state together, my heart to you as I seek to find the gradual to discover who we each are, here and now, and deliberate path to birth that is your own. and cherish that. I have felt your welcome and the warm It is there, in those precious trusting mo- hand of fellowship these first weeks that I have ments, that the work of transition begins. been with you, meeting your leaders, sharing Blessings, Rev. -

Resistance and Transformation: Unitarian Universalist Social Justice History

RESISTANCE AND TRANSFORMATION: UNITARIAN UNIVERSALIST SOCIAL JUSTICE HISTORY A Tapestry of Faith Program for Adults BY REV. COLIN BOSSEN AND REV. JULIA HAMILTON © Copyright 2011 Unitarian Universalist Association. This program and additional resources are available on the UUA.org web site at www.uua.org/re/tapestry 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS WORKSHOP 1: INTRODUCTIONS................................................................................................................... 16 WORKSHOP 2: PROPHETIC, PARALLEL, AND INSTITUTIONAL ............................................................. 27 WORKSHOP 3: THE RESPONSE TO SLAVERY ............................................................................................ 42 WORKSHOP 4: THE NINETEENTH CENTURY WOMEN'S PEACE MOVEMENT .................................... 58 WORKSHOP 5: JUST WAR, PACIFISM, AND PEACEMAKING .................................................................. 77 WORKSHOP 6: RELIGIOUS FREEDOM ON THE MARGINS OF EMPIRE ................................................. 96 WORKSHOP 7: UTOPIANISM ........................................................................................................................ 106 WORKSHOP 8: COUNTER-CULTURE .......................................................................................................... 117 WORKSHOP 9: FREE SPEECH ....................................................................................................................... 128 WORKSHOP 10: TAKING POLITICS PUBLIC ............................................................................................. -

Appendix EE.09 – Cultural Resources

Appendix EE.09 – Cultural Resources Tier 1 Final EIS Volume 1 NEC FUTURE Appendix EE.09 - Cultural Resources: Data Geography Affected Environment Environmental Consequences Context Area NHL NRHP NRE NHL NRHP NRE NHL NRHP NRE NHL NRHP NRE NHL NRHP NRE NHL NRHP NRE State County Existing NEC including Existing NEC including Existing NEC including Preferred Alternative Preferred Alternative Preferred Alternative Hartford/Springfield Line Hartford/Springfield Line Hartford/Springfield Line DC District of Columbia 10 21 0 10 21 0 0 3 0 0 4 0 49 249 0 54 248 0 MD Prince George's County 0 7 0 0 7 0 0 0 0 0 2 0 1 23 0 1 23 0 MD Anne Arundel County 0 3 0 0 3 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 8 0 0 8 0 MD Howard County 0 1 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 3 0 1 3 0 MD Baltimore County 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 9 0 0 10 0 MD Baltimore City 3 44 0 3 46 0 0 1 0 0 5 0 25 212 0 26 213 0 MD Harford County 0 5 0 0 7 0 0 0 0 0 2 0 1 12 0 1 15 0 MD Cecil County 0 6 2 0 8 2 0 0 2 0 1 2 0 11 2 0 11 2 DE New Castle County 3 64 2 3 67 2 0 2 1 0 5 2 3 187 1 4 186 2 PA Delaware County 0 4 0 1 5 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 18 0 1 18 0 PA Philadelphia County 9 85 1 10 87 1 0 2 1 3 4 1 57 368 1 57 370 1 PA Bucks County 3 8 1 3 8 1 0 1 1 1 1 1 3 15 1 3 15 1 NJ Burlington County 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 17 0 1 17 0 NJ Mercer County 1 9 1 1 10 1 0 0 2 0 0 2 5 40 1 6 40 1 NJ Middlesex County 1 20 2 1 20 2 0 0 1 0 1 1 1 42 2 1 42 2 NJ Somerset County 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 4 0 0 4 0 NJ Union County 1 9 1 1 10 1 0 1 1 0 2 1 2 17 1 2 17 1 NJ Essex County 1 24 1 1 26 1 0 1 1 0 1 1 1 65 1 1 65 1 NJ Hudson County -

1944 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD-SENATE 'F( 4685 REPORTS of Comrvllttees on PUBLIC Whiteside and St

1944 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD-SENATE 'f( 4685 REPORTS OF COMrvllTTEES ON PUBLIC Whiteside and St. Luke's Hospital; without Derry, N. H., favoring the passage of Senate BILLS AND RESOLUTIONS amendment (Rept. No. 1464). Referred to bill 1767 as reported by the House Commit the Committee of the Whole House. tee on World War Veterans" Legislation, with Under clause 2 of rule XIII, reports of out amendment; to the Committee on World committees were delivered to the Clerk PUBLIC BILLS AND RESOLUTIONS War Veterans' Legislation. for printing and reference to the proper 5703. By the SPEAKER: Petition of the calendar, as follows: Under clause 3 of rule XXII, public secretary, National Association of State Audi· Mr. WALTER: Committee on the Judiciary. bills and resolutions were introduced and tors, Comptrollers, and Treasurers, petition H. R. 4065. A b111 further defining the num severally referred as follows: ing consideration of their resolution with ber and duties of criers and bailiffs in United reference to post-war financing by the States; By Mr. HERTER: to the Committee on Ways and Means. State.S courts and regulating their compensa H. R. 4822. A bill to provide that all sums tion; without amendment (Rept. No. 1465). receiveq by the United States from the liqui 5704. Also, petition of the Union Repub Referred to the Committee of the Whole dation of Government property be applied lican Prog_ressive Party of Puerto Rico, peti House on the state of the Union. to the reduction of the public debt; to the tioning consideration of their resolution with Mr. WALTER: Committee on the Judiciary.