Directors' Duties and Corporate Social

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

C:\Documents and Settings\All Users\Sean\Logos

C:\Documents and Settings\All Users\Sean\Logos 7 ELEVEN 1.eps 7 ELEVEN 2.eps 7UP 1.eps 7UP 2.eps 7UP CHERRY 1.eps 7UP CHERRY 2.eps 7UP DIET 1.eps 7UP DIET 2.eps 7UP DIET CHERR... 7UP DIET CHERR... S & H GREEN STA... SAA.eps SAAB AUTOMOBIL... SAAB AUTOMOBIL... SABENA AIR 1.eps SABENA AIR 2.eps SABENA WORLD ... SABRE BOATS.eps SACHS.eps SAFE PLACE.eps SAFECO.eps SAFEWAY 1.eps SAFEWAY 2.eps SAINSBURYS 1.eps SAINSBURYS 2.eps SAINSBURYS BAN... SAINSBURYS BAN... SAINSBURYS HO... SAINSBURYS HO... SAINSBURYS SAV... Page 1 C:\Documents and Settings\All Users\Sean\Logos SAINSBURYS SAV... SAKS 5TH AVENU... SAKS 5TH AVENU... SAKS 5TH AVENU... SALEM.eps SALOMON.eps SALON SELECTIV... SALTON.eps SALVATION ARMY... SAMS CLUB.eps SAMS NET.eps SAMS PUBLISHIN... SAMSONITE.eps SAMSUNG 1.eps SAMSUNG 2.eps SAN DIEGO STAT... SAN DIEGO UNIV ... SAN DIEGO UNIV ... SAN JOSE UNIV 1.... SAN JOSE UNIV 2.... SANDISK 1.eps SANDISK 2.eps SANFORD.eps SANKYO.eps SANSUI.eps SANYO.eps SAP.eps SARA LEE.eps SAS AIR 1.eps SAS AIR 2.eps Page 2 C:\Documents and Settings\All Users\Sean\Logos SASKATCHEWAN ... SASSOON.eps SAT MEX.eps SATELLITE DIREC... SATURDAY MATIN... SATURN 1.eps SATURN 2.eps SAUCONY.eps SAUDI AIR.eps SAVIN.eps SAW JAMMER PR... SBC COMMUNICA... SC JOHNSON WA... SCALA 1.eps SCALA 2.eps SCALES.eps SCCA.eps SCHLITZ BEER.eps SCHMIDT BEER.eps SCHWINN CYCLE... SCIFI CHANNEL.eps SCIOTS.eps SCO.eps SCORE INT'L.eps SCOTCH.eps SCOTIABANK 1.eps SCOTIABANK 2.eps SCOTT PAPER.eps SCOTT.eps SCOTTISH RITE 1... -

Fund Holdings

Wilmington International Fund as of 7/31/2021 (Portfolio composition is subject to change) ISSUER NAME % OF ASSETS ISHARES MSCI CANADA ETF 3.48% TAIWAN SEMICONDUCTOR MANUFACTURING CO LTD 2.61% DREYFUS GOVT CASH MGMT-I 1.83% SAMSUNG ELECTRONICS CO LTD 1.79% SPDR S&P GLOBAL NATURAL RESOURCES ETF 1.67% MSCI INDIA FUTURE SEP21 1.58% TENCENT HOLDINGS LTD 1.39% ASML HOLDING NV 1.29% DSV PANALPINA A/S 0.99% HDFC BANK LTD 0.86% AIA GROUP LTD 0.86% ALIBABA GROUP HOLDING LTD 0.82% TECHTRONIC INDUSTRIES CO LTD 0.79% JAMES HARDIE INDUSTRIES PLC 0.78% DREYFUS GOVT CASH MGMT-I 0.75% INFINEON TECHNOLOGIES AG 0.74% SIKA AG 0.72% NOVO NORDISK A/S 0.71% BHP GROUP LTD 0.69% PARTNERS GROUP HOLDING AG 0.65% NAVER CORP 0.61% HUTCHMED CHINA LTD 0.59% LVMH MOET HENNESSY LOUIS VUITTON SE 0.59% TOYOTA MOTOR CORP 0.59% HEXAGON AB 0.57% SAP SE 0.57% SK MATERIALS CO LTD 0.55% MEDIATEK INC 0.55% ADIDAS AG 0.54% ZALANDO SE 0.54% RIO TINTO LTD 0.52% MERIDA INDUSTRY CO LTD 0.52% HITACHI LTD 0.51% CSL LTD 0.51% SONY GROUP CORP 0.50% ATLAS COPCO AB 0.49% DASSAULT SYSTEMES SE 0.49% OVERSEA-CHINESE BANKING CORP LTD 0.49% KINGSPAN GROUP PLC 0.48% L'OREAL SA 0.48% ASSA ABLOY AB 0.46% JD.COM INC 0.46% RESMED INC 0.44% COLOPLAST A/S 0.44% CRODA INTERNATIONAL PLC 0.41% AUSTRALIA & NEW ZEALAND BANKING GROUP LTD 0.41% STRAUMANN HOLDING AG 0.41% AMBU A/S 0.40% LG CHEM LTD 0.40% LVMH MOET HENNESSY LOUIS VUITTON SE 0.39% SOFTBANK GROUP CORP 0.39% NOVARTIS AG 0.38% HONDA MOTOR CO LTD 0.37% TOMRA SYSTEMS ASA 0.37% IMCD NV 0.37% HONG KONG EXCHANGES & CLEARING LTD 0.36% AGC INC 0.36% ADYEN -

Single Sector Funds Portfolio Holdings

! Mercer Funds Single Sector Funds Portfolio Holdings December 2020 welcome to brighter Mercer Australian Shares Fund Asset Name 4D MEDICAL LTD ECLIPX GROUP LIMITED OOH MEDIA LIMITED A2 MILK COMPANY ELDERS LTD OPTHEA LIMITED ABACUS PROPERTY GROUP ELECTRO OPTIC SYSTEMS HOLDINGS LTD ORICA LTD ACCENT GROUP LTD ELMO SOFTWARE LIMITED ORIGIN ENERGY LTD ADBRI LTD EMECO HOLDINGS LTD OROCOBRE LTD ADORE BEAUTY GROUP LTD EML PAYMENTS LTD ORORA LTD AFTERPAY LTD ESTIA HEALTH LIMITED OZ MINERALS LTD AGL ENERGY LTD EVENT HOSPITALITY AND ENTERTAINMENT PACT GROUP HOLDINGS LTD ALKANE RESOURCES LTD EVOLUTION MINING LTD PARADIGM BIOPHARMACEUTICALS LTD ALS LIMITED FISHER & PAYKEL HEALTHCARE CORP LTD PENDAL GROUP LTD ALTIUM LTD FLETCHER BUILDING LTD PERENTI GLOBAL LTD ALUMINA LTD FLIGHT CENTRE TRAVEL GROUP LTD PERPETUAL LTD AMA GROUP LTD FORTESCUE METALS GROUP LTD PERSEUS MINING LTD AMCOR PLC FREEDOM FOODS GROUP LIMITED PHOSLOCK ENVIRONMENTAL TECHNOLOGIES AMP LTD G8 EDUCATION LTD PILBARA MINERALS LTD AMPOL LTD GALAXY RESOURCES LTD PINNACLE INVESTMENT MANAGEMENT GRP LTD ANSELL LTD GDI PROPERTY GROUP PLATINUM INVESTMENT MANAGEMENT LTD APA GROUP GENWORTH MORTGAGE INSRNC AUSTRALIA LTD POINTSBET HOLDINGS LTD APPEN LIMITED GOLD ROAD RESOURCES LTD POLYNOVO LIMITED ARB CORPORATION GOODMAN GROUP PTY LTD PREMIER INVESTMENTS LTD ARDENT LEISURE GROUP GPT GROUP PRO MEDICUS LTD ARENA REIT GRAINCORP LTD QANTAS AIRWAYS LTD ARISTOCRAT LEISURE LTD GROWTHPOINT PROPERTIES AUSTRALIA LTD QBE INSURANCE GROUP LTD ASALEO CARE LIMITED GUD HOLDINGS LTD QUBE HOLDINGS LIMITED ASX LTD -

Women in the Redex Around Australia Reliability Trials of the 1950S

University of Wollongong Research Online Faculty of Arts - Papers (Archive) Faculty of Arts, Social Sciences & Humanities 1-1-2011 The flip side: women in the Redex Around Australia Reliability Trials of the 1950s Georgine W. Clarsen University of Wollongong, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/artspapers Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons, and the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Clarsen, Georgine W., The flip side: women in the Redex Around Australia Reliability Trials of the 1950s 2011, 17-36. https://ro.uow.edu.au/artspapers/1166 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] The Flip Side: Women on the Redex Around Australia Reliability trials of the 1950s Georgine Clarsen In August 1953 almost 200 cars set off from the Sydney Showgrounds in what popular motoring histories have called the biggest, toughest, most ambitious, demanding, ‘no-holds-barred’ race, which ‘caught the public imagination’ and ‘fuelled the nation with excitement’.1 It was the first Redex Around Australia Reliability Trial and organisers claimed it would be more testing than the famous Monte Carlo Rally through Europe and was the longest and most challenging motoring event since the New York-to-Paris race of 1908.2 That 1953 field circuited the eastern half of the continent, travelling north via Brisbane, Mt Isa and Darwin, passing through Alice Springs to Adelaide and returning to the start point in Sydney via Melbourne. Two Redex trials followed, in 1954 and 1955, and each was longer and more demanding than the one before. -

For Personal Use Only Use Personal For

Caltex Australia Limited Australia Caltex 2018 Annual Report Annual 2018 2018 Annual Report Capability Scale For personal use only FUELS & INFRASTRUCTURE International sourcing and supply 0700 HRS Kurnell Fuel Import Terminal Caltex Australia Limited 2018 Annual Report Caltex Supply Chain 2 Refining 3 Integrated Australian fuel supply chain 5 Retail fuel and convenience 7 Network of Assets 8 2018 Highlights 10 Message from the Chairman and the Managing Director & CEO 12 Operations Reports 16 Fuels & Infrastructure 17 Convenience Retail 21 Our people taking us further 25 Our approach to sustainability 29 2018 Financial Report 33 On the Cover Ampol is Caltex’s international trading and shipping team based in Singapore. It sources petroleum products from global markets and connects their supply chains with our market leading infrastructure positions, such as our import terminal in Kurnell, New South Wales (pictured). This international supply capability underpins Caltex’s reputation for reliable supply to wholesale customers, while ensuring the competitiveness of our refining and retail operations. Ampol also manages supply to our first international acquisition, Gull New Zealand, our partner Seaoil in the Philippines, in which Caltex holds a 20% equity interest, and our other international wholesale customers. About this Report This 2018 Annual Report for Caltex Australia LimitedFor personal use only (ACN 004 201 307) has been prepared as at 26 February 2019. Please note that terms such as Caltex and Caltex Australia have the same meaning as Caltex Group, unless the context requires otherwise. An interactive version of the Annual Report is available on our website. Visit www.caltex.com.au to download or view a copy. -

September 2019 Quarter 71

y 5 6 Equit 2019 High Conviction High September Quarterly Newsletter No. Selector Fund Fund In this quarterly edition, we review performance and attribution. We discuss reporting season, we introduce PolyNovo and profile Octopart, a business within Altium. “On the Road” follows our overseas travels during the period. We look at NPS culture and review APRA’s first Federal Court case in a decade. Photo. We visited The Long Room, Trinity College, Dublin, Ireland. In 1801, it was established as a designated legal deposit entitled to a copy of every book published on the two islands. Selector Funds Management Limited ACN 102756347 AFSL 225316 Level 8, 10 Bridge Street Sydney NSW 2000 Australia Tel 612 8090 3612 www.selectorfund.com.au P f Selector is a Sydney based fund manager. Our team combines deep experience in financial markets with diversity of background and thought. We believe in long-term wealth creation and building lasting relationships with our investors. We focus on stock selection, the funds are high conviction, concentrated and index unaware. As a result, the portfolios have low turnover and produce tax effective returns. Selector has a 15-year track record of outperformance and we continue to seek businesses with leadership qualities, run by competent management teams, underpinned by strong balance sheets and with a focus on capital management. Selector High Conviction Equity Fund Quarterly Newsletter #65 CONTENTS IN BRIEF – SEPTEMBER QUARTER 3 PORTFOLIO OVERVIEW 5 PORTFOLIO CONTRIBUTORS 7 REPORTING SEASON COMMENTARY 8 POLYNOVO 32 OCTOPART – BUSINESS WITHIN A BUSINESS 44 ON THE ROAD 50 THE NPS CULTURE 57 APRA – CLASS ACTION? 68 OF INTEREST – BRAND VALUES 70 COMPANY VISIT DIARY – SEPTEMBER 2019 QUARTER 71 2 Selector Funds Management IN BRIEF – SEPTEMBER QUARTER Dear Investor, The world never seems too far away from a crisis. -

2021 Shannons Autumn Timed Auction Results

2021 SHANNONS AUTUMN TIMED AUCTION RESULTS Please note: All prices listed are in Australian Dollars (AUD). Prices do not include the 5% buyers premium. LOT DESCRIPTION PRICE 1 TRICYCLE - c1950's Childs Cyclops Style Trike $435 2 DECANTER - set of 3 Grand Prix International Grill decanters - Ford, Mercedes, Jaguar ( 20.5 x 13cm) $405 3 BADGE BOARD - Assorted Veteran, Vintage & Classic Rally Badges Qty - 73 $850 4 OIL TINS ASSORTED - (1 x Caltex, 2 x Ampol) $300 5 4 x Assorted Small Oil Cans ( Castrol, Ampol, Bardahl, Laurel Kerosene) $200 6 PETROL TINS - 6 x Tins: Esso,Wakefield, Duckhams, Ampol, Plume, Lockheed $400 7 HI BOY - Castrol Highboy with pump Restored $680 8 HI BOY - SHELL Livery (Unrestored) $510 9 LUBE STAND - Shell Lubrications Guide on stand $600 10 Glass Barbershop Sign - Gents Hairdressing (45 x 110cm) $200 11 Railway Lamp $451 12 MOVIE POSTERS - Framed Mad Max One & Mad Max 2 Movie Posters (107 x 74cm) $1,450 13 PICNIC RADIO - Air Chief MN-CBE with Adaptor Fits EJ / EH Holden NACSO accessory $301 14 ENAMEL SIGN - Peter's Ice Cream Sign - Single sided Original (183 x 45cm) $1,350 15 RECORD PLAYER - ARC1000 Under Dash 12 Stacker Car Record Player for 45's - Universal $1,201 16 FRAMED BANNER - Vintage Texaco Calico Banner $200 17 GOLDEN FLEECE Aluminium Ram $800 18 CAST IRON - Michelin Man (58 x 12 wide) $2,100 19 LIGHT BOX - AMPOL PRODUCTS BAR $550 20 ENAMEL SIGN - Authorised Stockist of Perkins Diesel Spare Parts Sign (48 x 31 cm ) $1,500 21 ENAMEL SIGN - Ford Sales & Service Double sided - Original (76 x 30.5 cm) $2,200 22 SIGNS - Castrol Wakefield in enamel (Single Sided) & Castrol Masterpiece in Tin (Single sided) (76 x 30.5cm) $952 SCALEXTRICS SET VINTAGE - Slot Car Set Scale 1:25 with extra track in box, made in England (2amp) and power unit . -

EVC-State-Of-Evs-2020-Report.Pdf

STATE OF ELECTRIC VEHICLES AUGUST 2020 electricvehiclecouncil.com.au STATE OF ELECTRIC VEHICLES AUGUST 2020 electricvehiclecouncil.com.au 06 2020 HIGHLIGHTS 09 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY CONTENTS 13 CHAPTER 1: MARKET UPDATE 13 Electric vehicle sales 14 COVID-19 15 Consumer attitudes survey 22 Case study: Lane Cove development building now for the electrified future 24 CHAPTER 2: AUSTRALIA'S EV INDUSTRY 24 Passenger vehicles 28 Bikes and scooter 29 Commercial vehicles and buses 36 Case study: East waste makes haste, leading the way on electric garbage 38 CHAPTER 3: CHARGING INFRASTRUCTURE 38 Public charging 42 Home and workplace charging 44 Case study: Evie Networks, the Aussie company building a nation-wide ultra-fast charging network 46 CHAPTER 4: EV MINING AND MANUFACTURING 46 Battery value chain 51 Charger manufacturing 52 Electric vehicle manufacturing 58 Case study: Voltra and BHP break new ground underground CHAPTER 5: EVS, THE ENVIRONMENT, 60 AND THE ENERGY GRID 60 Emissions impact 61 Battery stewardship 64 Built environment 67 Integration with the grid 72 Case study: Realising electric vehicle-to-grid services CHAPTER 2: AUSTRALIA'S EV INDUSTRY 74 CHAPTER 6: EV POLICY 75 Policy progress and scorecard 77 Policy highlights 80 APPENDIX 80 Appendix 1: Carmakers' commitments to electric vehicles 84 Appendix 2: Electric vehicle model availability 90 Appendix 3: Carmakers' investments into secondary battery applications 90 Appendix 4: Bus partnerships in Australia 93 REFERENCES 6 ELECTRIC VEHICLE COUNCIL 2020 highlights In 2019, EV sales increased -

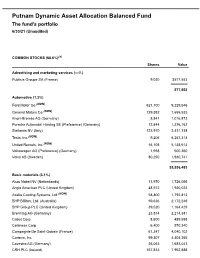

Dynamic Asset Allocation Balanced Fund Q3 Portfolio Holdings

Putnam Dynamic Asset Allocation Balanced Fund The fund's portfolio 6/30/21 (Unaudited) COMMON STOCKS (68.6%)(a) Shares Value Advertising and marketing services (—%) Publicis Groupe SA (France) 9,030 $577,553 577,553 Automotive (1.3%) Ford Motor Co.(NON) 621,100 9,229,546 General Motors Co.(NON) 129,382 7,655,533 Knorr-Bremse AG (Germany) 8,841 1,016,872 Porsche Automobil Holding SE (Preference) (Germany) 12,844 1,376,162 Stellantis NV (Italy) 123,970 2,431,338 Tesla, Inc.(NON) 9,206 6,257,318 United Rentals, Inc.(NON) 16,108 5,138,613 Volkswagen AG (Preference) (Germany) 1,998 500,360 Volvo AB (Sweden) 80,250 1,930,741 35,536,483 Basic materials (3.1%) Akzo Nobel NV (Netherlands) 13,970 1,726,066 Anglo American PLC (United Kingdom) 48,572 1,930,023 Axalta Coating Systems, Ltd.(NON) 58,800 1,792,812 BHP Billiton, Ltd. (Australia) 59,636 2,172,246 BHP Group PLC (United Kingdom) 39,520 1,164,429 Brenntag AG (Germany) 23,814 2,214,381 Cabot Corp. 8,600 489,598 Celanese Corp. 6,400 970,240 Compagnie De Saint-Gobain (France) 61,347 4,040,102 Corteva, Inc. 99,307 4,404,265 Covestro AG (Germany) 26,063 1,683,043 CRH PLC (Ireland) 157,813 7,952,888 Dow, Inc. 93,022 5,886,432 DuPont de Nemours, Inc. 130,372 10,092,097 Eastman Chemical Co. 21,500 2,510,125 Eiffage SA (France) 8,245 838,825 FMC Corp. 4,000 432,800 Fortescue Metals Group, Ltd. -

View Annual Report

Caltex Australia Limited Australia Caltex 2018 Annual Report Annual 2018 2018 Annual Report Capability Scale FUELS & INFRASTRUCTURE International sourcing and supply 0700 HRS Kurnell Fuel Import Terminal Caltex Australia Limited 2018 Annual Report Caltex Supply Chain 2 Refining 3 Integrated Australian fuel supply chain 5 Retail fuel and convenience 7 Network of Assets 8 2018 Highlights 10 Message from the Chairman and the Managing Director & CEO 12 Operations Reports 16 Fuels & Infrastructure 17 Convenience Retail 21 Our people taking us further 25 Our approach to sustainability 29 2018 Financial Report 33 On the Cover Ampol is Caltex’s international trading and shipping team based in Singapore. It sources petroleum products from global markets and connects their supply chains with our market leading infrastructure positions, such as our import terminal in Kurnell, New South Wales (pictured). This international supply capability underpins Caltex’s reputation for reliable supply to wholesale customers, while ensuring the competitiveness of our refining and retail operations. Ampol also manages supply to our first international acquisition, Gull New Zealand, our partner Seaoil in the Philippines, in which Caltex holds a 20% equity interest, and our other international wholesale customers. About this Report This 2018 Annual Report for Caltex Australia Limited (ACN 004 201 307) has been prepared as at 26 February 2019. Please note that terms such as Caltex and Caltex Australia have the same meaning as Caltex Group, unless the context requires otherwise. An interactive version of the Annual Report is available on our website. Visit www.caltex.com.au to download or view a copy. Shareholders can request a printed copy of the Annual Report free of charge by emailing [email protected] or writing to the Company Secretary, Caltex Australia Limited, Level 24, 2 Market Street, Sydney Lani Rauschenbach, CSA, NSW 2000 Australia. -

Summary of Holdings Sub-Adviser: Arrowstreet Capital, Limited Partnership Holdings As Of: 7/30/2021 Fund: International Stock Fund

Summary of Holdings Sub-Adviser: Arrowstreet Capital, Limited Partnership Holdings as of: 7/30/2021 Fund: International Stock Fund Quantity Security Title Security ID Symbol % of Portfolio EQUITIES 6,263 ASML HOLDING NV B929F46 ASML NA 2.68 % 64,406 Samsung Electronics 6771720 005930 2.46 % 782,500 Sberbank-CLS 4767981 SBER RX 1.83 % 74,213 Glaxosmithkline PLC ADR 37733W105 GSK 1.67 % 20,765 Taiwan Semiconductor Mfg., Inc 874039100 TSM 1.36 % 34,577 BHP Billiton PLC 05545E209 BBL 1.26 % 24,250 Lukoil PJSC B59SNS8 LKOH RM 1.17 % 53,079 ABB Ltd. 000375204 ABB 1.09 % 869,800 Itausa - Investimentos Itau 2458771 ITSA4BZ 1.06 % 4,784 Roche Holding AG- Genusschein 7110388 ROG SW 1.03 % 5,367 Atlassian Corp PLC G06242104 TEAM 0.98 % 78,600 Vale SA 2196286 VALE3 0.94 % 3,000 KEYENCE CORP 6490995 6861 JP 0.93 % 50,800 MS&AD Insurance Group B2Q4CS1 8725 JT 0.88 % 2,085,400 PetroChina Company Ltd. BP3R206 0.85 % 15,084 Brenntag AG B4YVF56 BNR GR 0.84 % 2,900 Nintendo Co. Ltd 6639550 7974 JT 0.83 % 37,168 Industrivarden AB B1VSK54 INDUC 0.80 % 131,975 Porsche Automobil Holding SE 73328P106 POAHY 0.80 % 52,000 Minebea Co. LTD 6642406 6479 JP 0.79 % 14,214 Hynix Semiconductor Inc 6450267 000660 0.78 % 58,300 Idemitsu Kosan Co. B1FF8P7 5019 JP 0.77 % 2,199,440 Guanghui Energy Company Ltd. BP3R3N6 0.77 % 65,014 Vale SA 91912E105 VALE 0.76 % 20,889 Covestro AG BYTBWY9 1COV GY 0.75 % 3,785 MMC Norilsk Nickel PJSC B5B1TX2 GMKN RM 0.73 % 10,848 Rea Group Limited 6198578 REA AU 0.72 % 1,915,580,000 Vtb Bank PJSC B5B1TP4 VTBR RX 0.71 % 19,632 Samsung Electronics 6773812 005935 0.69 % 47,569 Investor A.B. -

Lot# Description Qty Bid Amount 1 New Pegasus Neon Light up Sign (Working) 1100 X 800 1 130.00

Lot# Description Qty Bid Amount 1 New Pegasus Neon Light Up Sign (Working) 1100 x 800 1 130.00 2 New Pegasus Neon Light Up Sign (Working) 1100 x 800 1 100.00 3 2 x Modern Tin Shell Signs 550 x 390 1 70.00 4 2 x Modern Shell Tin Signs 350 x 520 1 100.00 5 Modern GTS Monaro Tin Sign 650 x 600 1 80.00 6 Modern Golden Fleece Tin Sign 730 x 400 1 70.00 7 Modern Shell Tin Sign 360 x 460 1 40.00 8 Modern Golden Fleece Tin Sign 300 x 470 1 50.00 9 2 x Modern Tin Signs Falcon and Valiant 600 x 400 1 30.00 10 Modern Tin Buick sign 600 x 300 1 15.00 11 Modern Tin Kombi sign 600 x 400 1 20.00 12 Modern Tin Atlantic Sign 550 x 430 1 60.00 13 Modern Tin Caltex Sign 390 x 570 1 50.00 14 Modern Tin Garage Sign 500 x 250 1 30.00 15 2 x Modern Tin Motor Bike Signs 440 x 300 1 30.00 16 Modern Tin Muscle Car Garage Sign 600 x 400 1 90.00 17 Modern Tin Garage Sign 600 x 400 1 40.00 18 Modern Tin Garage Local Dealer Sign 600 x 400 1 30.00 19 Castrol Tin Sign Reproduction 400mm 1 30.00 20 2 X Enamel Signs Golden Fleece & Red Indian 240mm Reproduction 1 100.00 21 2 x Enamel Signs inc Globe & Musgo 300mm Reproduction 1 100.00 22 Modern Tin Sign WB Ute 600 x 400 1 50.00 23 Modern Tin Sign FC Holden 600 x 400 1 50.00 24 Modern Tin Sign Torana 600 x 400 1 50.00 25 Modern Tin Sign Shell Motor Oil 600 x 400 1 40.00 26 Modern Shell Tin Sign EH Holden 600 x 400 1 40.00 27 Modern Tin Sign Shell Petrol and Oil 600 x 400 1 50.00 28 2 x Reproduction Tin and Enamel Signs inc Texaco and Mobilgas 320 x 400 1 30.00 29 2 x Modern Shell Tin Signs 600 x 400 1 110.00 30 Modern Tin