Theft of Scrap Metal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

City of Nampa Special City Council Meeting Budget Workshop Livestreaming at July 13, 2020 8:00 AM

City of Nampa Special City Council Meeting Budget Workshop Livestreaming at https://livestream.com/cityofnampa July 13, 2020 8:00 AM Call to Order Prayer Roll Call Opening Comments - Mayor Part I – Foundational review, Revenues & Budget Summary (Doug Racine) • Foundational Budget Discussion • Fiscal 2021 Budget Summary • Overall Budget Risks and Opportunities • Fund Budgets – Summarized review • General Government Summarized Budget Break Action Item: Council Discussion & Vote on FY2021 Budgets: Part II – Departmental Budgets, Capital Budgets, Grants & Position Control (Ed Karass) • Budget Development introduction (1) Departmental Budget Reviews 1-1. Clerks 1-2. Code Enforcement 1-3. Econ Development 1-4. Facilities 1-5. Finance 1-6. Legal 1-7. Workforce Development 1-8. IT 1-9. Mayor & City Council 1-10. General Government Lunch Break (1) Continued Review of Departmental Budget Reviews 1-11. Public Work Admin 1-12. Public Works Engineering 1-13. Fire 1-14. Police Page 1 of 3 City of Nampa Special City Council Meeting Budget Workshop Livestreaming at https://livestream.com/cityofnampa July 13, 2020 8:00 AM (2) Special Revenue, Enterprise & Internal Service Funds 2-0. 911 2-1. Civic Center/Ford Idaho Center 2-2. Family Justice Center 2-3. Library 2-4. Parks & Recs (Incl Golf) 2-5. Stormwater 2-6. Streets / Airport 2-6. Water / Irrigation 2-7. Wastewater 2-8. Environmental Compliance 2-9. Sanitation / Utility Billing Break (2) Continued Review of Special Revenue, Enterprise & Internal Service Funds 2-10. Building / Development Services 2-11. Planning & Zoning 2-12. Fleet (4) Grants (5) Impact Fees (6) Capital Budget Review 6-0. -

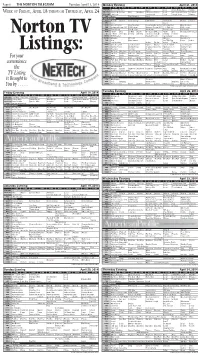

06 4-15-14 TV Guide.Indd

Page 6 THE NORTON TELEGRAM Tuesday, April 15, 2014 Monday Evening April 21, 2014 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 KHGI/ABC Dancing With Stars Castle Local Jimmy Kimmel Live Nightline WEEK OF FRIDAY, APRIL 18 THROUGH THURSDAY, APRIL 24 KBSH/CBS 2 Broke G Friends Mike Big Bang NCIS: Los Angeles Local Late Show Letterman Ferguson KSNK/NBC The Voice The Blacklist Local Tonight Show Meyers FOX Bones The Following Local Cable Channels A&E Duck D. Duck D. Duck Dynasty Bates Motel Bates Motel Duck D. Duck D. AMC Jaws Jaws 2 ANIM River Monsters River Monsters Rocky Bounty Hunters River Monsters River Monsters CNN Anderson Cooper 360 CNN Tonight Anderson Cooper 360 E. B. OutFront CNN Tonight DISC Fast N' Loud Fast N' Loud Car Hoards Fast N' Loud Car Hoards DISN I Didn't Dog Liv-Mad. Austin Good Luck Win, Lose Austin Dog Good Luck Good Luck E! E! News The Fabul Chrisley Chrisley Secret Societies Of Chelsea E! News Norton TV ESPN MLB Baseball Baseball Tonight SportsCenter Olbermann ESPN2 NFL Live 30 for 30 NFL Live SportsCenter FAM Hop Who Framed The 700 Club Prince Prince FX Step Brothers Archer Archer Archer Tomcats HGTV Love It or List It Love It or List It Hunters Hunters Love It or List It Love It or List It HIST Swamp People Swamp People Down East Dickering America's Book Swamp People LIFE Hoarders Hoarders Hoarders Hoarders Hoarders Listings: MTV Girl Code Girl Code 16 and Pregnant 16 and Pregnant House of Food 16 and Pregnant NICK Full H'se Full H'se Full H'se Full H'se Full H'se Full H'se Friends Friends Friends SCI Metal Metal Warehouse 13 Warehouse 13 Warehouse 13 Metal Metal For your SPIKE Cops Cops Cops Cops Cops Cops Cops Cops Jail Jail TBS Fam. -

06 4-15 TV Guide.Indd 1 4/15/08 7:49:32 AM

PAGE 6 THE NORTON TELEGRAM Tuesday, April 15, 2008 Monday Evening April 21, 2008 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 KHGI/ABC Dancing With the Stars Samantha Bachelor-Lond Local Nightline Jimmy Kimmel Live WEEK OF FRIDAY , APRIL 18 THROUGH THURSDAY , APRIL 24 KBSH/CBS Big Bang How I Met Two Men Rules CSI: Miami Local Late Show-Letterman Late Late KSNK/NBC Deal or No Deal Medium Local Tonight Show Late FOX Bones House Local Cable Channels A&E Intervention Intervention I Survived Crime 360 Intervention AMC Ferris Bueller Teen Wolf StirCrazy ANIM Petfinder Animal Cops Houston Animal Precinct Petfinder Animal Cops Houston CNN CNN Election Center Larry King Live Anderson Cooper 360 Larry King Live DISC Dirty Jobs Dirty Jobs Verminators How-Made How-Made Dirty Jobs DISN Finding Nemo So Raven Life With The Suite Montana Replace Kim E! Keep Up Keep Up True Hollywood Story Girls Girls E! News Chelsea Daily 10 Girls ESPN MLB Baseball Baseball Tonight SportsCenter Fastbreak Baseball Norton TV ESPN2 Arena Football Football E:60 NASCAR Now FAM Greek America's Prom Queen Funniest Home Videos The 700 Club America's Prom Queen FX American History X '70s Show The Riches One Hour Photo HGTV To Sell Curb Potential Potential House House Buy Me Sleep To Sell Curb HIST Modern Marvels Underworld Ancient Discoveries Decoding the Past Modern Marvels LIFE Reba Reba Black and Blue Will Will The Big Match MTV True Life The Paper The Hills The Hills The Paper The Hills The Paper The Real World NICK SpongeBob Drake Home Imp. -

06 9/2 TV Guide.Indd 1 9/3/08 7:50:15 AM

PAGE 6 THE NORTON TELEGRAM Tuesday, September 2, 2008 Monday Evening September 8, 2008 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 KHGI/ABC H.S. Musical CMA Music Festival Local Nightline Jimmy Kimmel Live KBSH/CBS Big Bang How I Met Two Men Christine CSI: Miami Local Late Show-Letterman Late Late WEEK OF FRIDAY , SEPT . 5 THROUGH THUR S DAY , SEPT . 11 KSNK/NBC Deal or No Deal Toughest Jobs Dateline NBC Local Tonight Show Late FOX Sarah Connor Prison Break Local Cable Channels A&E Intervention Intervention After Paranorml Paranorml Paranorml Paranorml Intervention AMC Alexander Geronimo: An American Legend ANIM Animal Cops Houston Animal Cops Houston Miami Animal Police Miami Animal Police Animal Cops Houston CNN CNN Election Center Larry King Live Anderson Cooper 360 Larry King Live DISC Mega-Excavators 9/11 Towers Into the Unknown How-Made How-Made Mega-Excavators DISN An Extremely Goofy Movie Wizards Wizards Life With The Suite Montana So Raven Cory E! Cutest Child Stars Dr. 90210 E! News Chelsea Chelsea Girls ESPN NFL Football NFL Football ESPN2 Poker Series of Poker Baseball Tonight SportsCenter NASCAR Now Norton TV FAM Secret-Teen Secret-Teen Secret-Teen The 700 Club Whose? Whose? FX 13 Going on 30 Little Black Book HGTV To Sell Curb Potential Potential House House Buy Me Sleep To Sell Curb HIST The Kennedy Assassin 9/11 Conspiracies The Kennedy Assassin LIFE Army Wives Tell Me No Lies Will Will Frasier Frasier MTV Exposed Exposed Exiled The Hills The Hills Exiled The Hills Exiled Busted Busted NICK Pets SpongeBob Fam. -

2019 Annual Report

ILLINOIS MOTOR 2019 VEHICLE THEFT Annual PREVENTION & Report INSURANCE VERIFICATION COUNCIL Secretary of State A private and public partnership effectively combating motor Jesse White vehicle theft and related crimes in Illinois since 1991. In Memory of Jerry Brady 1949-2019 Rest in Peace Motor Vehicle Theft Prevention and Insurance Verification Council Howlett Building, Room 461 Springfield, Illinois 62756 (217) 524-7087 (217) 782-1731 (Fax) www.cyberdriveillinois.com/MVTPIV/home.html Honorable Jesse White Illinois Secretary of State Brendan F. Kelly Director, Illinois State Police Charlie Beck Interim Superintendent, Chicago Police Department Honorable Kimberly M. Foxx Cook County State’s Attorney Honorable Jodi Hoos Peoria County State’s Attorney Brian B. Fengel Chief, Bartonville Police Department Larry D. Johnson Farmers Insurance Group Todd Feltman State Farm Insurance Company Dana Severinghaus Allstate Insurance Company Matt Gall COUNTRY Financial Insurance Company Heather Drake The Auto Club Group Table of Contents History of the Council …………………………………………………………………………… 5 MVTPIV Council Members ……………………………………………………………………. 6 Grant Review Committee Members ……………………………………………………… 10 MVTPIV Council Staff ……………………………………………………………………………. 10 Statewide Motor Vehicle Theft Trends …………………………………………………. 11 Cook County Motor Vehicle Theft Trends ……………………………………………… 12 Countywide Motor Vehicle Theft Trends ………………………………………………. 13 Overview of Council Programs and Activity Council Programs 1992-2018 ……………………………………………………. 14 Council Activity 2019 …………………………………………………………………. -

Curriculum Vitae

CURRICULUM VITAE Benjamin F. Stickle Middle Tennessee State University Department of Criminal Justice Administration 1301 East Main Street - MTSU Box 238 Murfreesboro, Tennessee 37132 [email protected] www.benstickle.com (615) 898-2265 EDUCATION Doctor of Philosophy, 2015, Justice Administration University of Louisville, Louisville, Kentucky Master of Science, 2010, Justice Administration University of Louisville, Louisville, Kentucky Bachelor of Arts, 2005, Sociology Cedarville University, Cedarville, Ohio ACADEMIC POSITIONS Middle Tennessee State University, Department of Criminal Justice Administration 2019 – Present Associate Professor 2016 – 2019 Assistant Professor Campbellsville University, Department of Criminal Justice Administration 2014 – 2016 Assistant Professor 2011 – 2014 Instructor (Full-time) University of Louisville, Department of Justice Administration 2014 – 2015 Lecturer ADMINISTRATIVE POSITIONS Middle Tennessee State University, Department of Criminal Justice Administration 2018 – Present Coordinator, Online Bachelor of Criminal Justice Administration 2018 – Present Chair, Curriculum Committee Campbellsville University, Department of Criminal Justice Administration 2011-2016 Site Coordinator, Louisville Education Center PROFESSIONAL APPOINTMENTS & AFFILIATIONS 2019 – Present Affiliated Faculty, Political Economy Research Institute, Middle Tennessee State University 2017 – Present Senior Fellow for Criminal Justice, Beacon Center of Tennessee Ben Stickle CV, Page 2 AREAS OF SPECIALIZATION • Property Crime: Metal -

Determining the Perspective of a Reasonable Police Officer: an Evidence-Based Proposal

Volume 65 Issue 3 Villanova Law Review Article 3 10-7-2020 Determining the Perspective of a Reasonable Police Officer: An Evidence-Based Proposal Mitch Zamoff Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.villanova.edu/vlr Part of the Criminal Law Commons Recommended Citation Mitch Zamoff, Determining the Perspective of a Reasonable Police Officer: Anvidence-Based E Proposal, 65 Vill. L. Rev. 585 (2020). Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.villanova.edu/vlr/vol65/iss3/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Villanova University Charles Widger School of Law Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Villanova Law Review by an authorized editor of Villanova University Charles Widger School of Law Digital Repository. Zamoff: Determining the Perspective of a Reasonable Police Officer: An Ev 2020] DETERMINING THE PERSPECTIVE OF A REASONABLE POLICE OFFICER: AN EVIDENCE-BASED PROPOSAL MITCH ZAMOFF* ABSTRACT Excessive force jurisprudence in America is in disarray. Although the Supreme Court mandated over thirty years ago that courts determine the constitutionality of allegedly excessive force from the perspective of a rea- sonable officer on the scene, courts have never seemed more confused about how to make that determination. Without any definitive guidance on what evidence to consider in determining how a reasonable officer on the scene of an incident of allegedly excessive force would have behaved, courts are issuing haphazard, inconsistent decisions that are often difficult to reconcile -

'Drowning in Here in His Bloody Sea' : Exploring TV Cop Drama's

'Drowning in here in his bloody sea' : exploring TV cop drama's representations of the impact of stress in modern policing Cummins, ID and King, M http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10439463.2015.1112387 Title 'Drowning in here in his bloody sea' : exploring TV cop drama's representations of the impact of stress in modern policing Authors Cummins, ID and King, M Type Article URL This version is available at: http://usir.salford.ac.uk/id/eprint/38760/ Published Date 2015 USIR is a digital collection of the research output of the University of Salford. Where copyright permits, full text material held in the repository is made freely available online and can be read, downloaded and copied for non-commercial private study or research purposes. Please check the manuscript for any further copyright restrictions. For more information, including our policy and submission procedure, please contact the Repository Team at: [email protected]. Introduction The Criminal Justice System is a part of society that is both familiar and hidden. It is familiar in that a large part of daily news and television drama is devoted to it (Carrabine, 2008; Jewkes, 2011). It is hidden in the sense that the majority of the population have little, if any, direct contact with the Criminal Justice System, meaning that the media may be a major force in shaping their views on crime and policing (Carrabine, 2008). As Reiner (2000) notes, the debate about the relationship between the media, policing, and crime has been a key feature of wider societal concerns about crime since the establishment of the modern police force. -

Paramount Collection

Paramount Collection Airtight To control the air is to rule the world. Nuclear testing has fractured the Earth's crust, releasing poisonous gases into the atmosphere. Breathable air is now an expensive and rare commodity. A few cities have survived by constructing colossal air stacks which reach through the toxic layer to the remaining pocket of precious air above. The air is pumped into a huge underground labyrinth system, where a series of pipes to the surface feed the neighborhoods of the sealed city. It is the Air Force, known as the "tunnel hunters", that polices the system. Professor Randolph Escher has made a breakthrough in a top-secret project, the extraction of oxygen from salt water in quantity enough to return breathable air to the world. Escher is kidnapped by business tycoon Ed Conrad, who hopes to monopolize the secret process and make a fortune selling the air by subscription to the masses. Because Conrad Industries controls the air stacks, not subscribing to his "air service" would mean certain death. When Air Force Team Leader Flyer Lucci is murdered, his son Rat Lucci soon uncovers Conrad's involvement in his father's death and in Escher's kidnapping. Rat must go after Conrad, not only to avenge his father's murder, but to rescue Escher and his secret process as well. The loyalties of Rat's Air Force colleagues are questionable, but Rat has no choice. Alone, if necessary, he must fight for humanity's right to breathe. Title Airtight Genre Action Category TV Movie Format two hours Starring Grayson McCouch, Andrew Farlane, Tasma Walton Directed by Ian Barry Produced by Produced by Airtight Productions Proprietary Ltd. -

Commodity Metals Theft Task Force

HOUSE BILL 16-1182 BY REPRESENTATIVE(S) Court and Duran, Kagan, Lee, Salazar, Arndt, Fields, Lontine, Melton, Pabon, Priola, Rosenthal, Hullinghorst; also SENATOR(S) Cooke and Heath, Merrifield, Todd. CONCERNING THE CONTINUATION OF THE COMMODITY METALS THEFT TASK FORCE. Be it enacted by the General Assembly ofthe State ofColorado : SECTION 1. In Colorado Revised Statutes, 18-13-111, amend (8) (b.5), (9) (f), and (10) (b) as follows: 18-13-111. Purchases of commodity metals - violations - commodity metals theft task force - creation - composition - reports - legislative declaration - definitions - repeal. (8) For the purposes ofthis section, unless the context otherwise requires: (b.5) "Commodity metal" means a metal containing brass, copper; A copper alloy, INCLUDING BRONZE OR BRASS; OR aluminum. stainless steel, 01magnesium01 anothe1 metal haded on the connnodity maikets that sells fo1 fifty cents pct pound 01 greater. "Commodity metal 11 does not include precious metals such as gold, silver, or platinum. Capital letters indicate new material added to existing statutes; dashes through words indicate deletions from existing statutes and such material not part ofact. (9) (f) This subsection (9) is repealed, effective Joi)' 1, 2016 SEPTEMBER 1, 2025. Before the repeal, the commodity metals theft task force, created pursuant to this subsection (9), shall be reviewed as provided in section 2-3-1203, C.R.S. (10) (b) IN ORDER TO CONTINUE THE ABILITY OF THE STATE TO IDENTIFY CAUSES OF COMMODITY METAL THEFT AND PROVIDE REALISTIC SOLUTIONS TO THE THEFT PROBLEM, the general assembly further encourages law enforcement authorities in the state to repo1t thefts of connnodity metals occoning within thei:I jorisdictions to JOIN the scrap theft alert system maintained by the institute of scrap recycling industries, incorporated, or its successor organization, AND TO REPORT THEFTS OF COMMODITY METALS OCCURRING WITHIN THEIR JURISDICTIONS TO THIS SYSTEM. -

Impact of Bearing Vibration on Yarn Quality in Ring Frame

IOSR Journal of Polymer and Textile Engineering (IOSR-JPTE) e-ISSN: 2348-019X, p-ISSN: 2348-0181, Volume 2, Issue 3 (May - Jun. 2015), PP 50-59 www.iosrjournals.org Impact of Bearing Vibration on yarn quality in Ring Frame S Sundaresan*, Dr.M.Dhinakaran**, Arunraj Arumugam*** *Assistant professor (SRG), **Associate Professor (SRG), *** Assistant professor, Department of Textile Technology, Kumaraguru College of Technology, Coimbatore -641049, Tamil Nadu, India. Abstract: This digital generation makes everything vibrates in the world, some vibrations are good and useful and the rest fall under the dangerous category. In spinning industry, the impact of vibration is affecting the quality of yarn. The vibration of the tin roller shaft is measured in ring spinning machine LR G5/1 equipped with 1008 spindles. The vibration of the tin roller shaft is measured in various position of the machine (near gear end, middle portion of the machine and from the off end of the machine). The vibration of the bearing also noted with respect to the cop position ( ¼ stage, ½ stage and ¾ stage). With the help of accelerometer which consists of piezoelectric sensor used to measure the vibration and to measure the acceleration of the frequency spectrum. This sensor is placed on the bearing with the help of magnetic attachment to analyse the vibration by using FFT analyser. [1]. Introduction In modern days the ring spinning operates at the maximum speed up to 25000 rpm. The ring frame also consists of 1008 to 1220 spindles per machine. The effect of tin roller bearing vibration on yarn quality can be studied by measuring the vibration of tin roller shaft bearing at different points during the running condition. -

The Council of State Governments May 2014

the council of state governments may 2014 Scrap Metal Theft Is Legislation Working for States? Overview Insurance companies, law enforcement officials and industry watchdogs have called scrap metal theft— including copper, aluminum, nickel, stainless steel and scrap iron—one of the fastest-growing crimes in the United States. State leaders have taken notice, passing a flurry of legislation meant to curb metal theft and help law enforcement find and prosecute criminals. Researchers at The Council of State Gov- ernments, in collaboration with the Institute of Scrap Recycling Industries, set out to determine if all that legislation is having an impact on metal theft rates. To determine if state legislation has been effective at curbing metal theft, a thorough analysis is needed that starts with an evaluation of trends in metal theft incident rates at the state level. After an evaluation of the existing research and interviews with state and local officials and law enforcement per- sonnel across all 50 states, CSG researchers concluded that metal theft data for states are not available for analysis. Because metal theft is such a significant and widespread problem, and because accurately tracking metal theft is key to establishing evidence-based practices designed to both deter theft and to assist in the investigation and prosecution of theft, it is imperative that states evaluate ways to begin collecting these data. Moving forward, it is unlikely data will be available on a scale necessary to perform meaningful analysis unless a widespread effort is launched to create systems to document, track and report metal theft crime uniformly and consistently.