CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, NORTHRIDGE Rasquache Or Die

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ticket Monster?

004BILB06.QXP 2/5/09 6:52 PM Page 1 PUBLISHER HOWARD APPELBAUM EDITORIAL DIRECTOR BILL WERDE EDITORIAL EXECUTIVE EDITOR: ROBERT LEVINE 646-654-4707 DEPUTY EDITOR: Louis Hau 646-654-4708 SENIOR EDITORS: Jonathan Cohen 646-654-5582; Ann Donahue 323-525-2292 SPECIAL FEATURES EDITOR: Thom Duffy 646-654-4716 EDITORIALS | COMMENTARY | LETTERS INTERNATIONAL BUREAU CHIEF: Mark Sutherland 011-44-207-420-6155 OPINION EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR OF CONTENT AND PROGRAMMING FOR LATIN MUSIC AND ENTERTAINMENT: Leila Cobo (Miami) 305-361-5279 EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR OF CONTENT AND PROGRAMMING FOR TOURING AND LIVE ENTERTAINMENT: Ray Waddell (Nashville) 615-431-0441 EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR OF CONTENT AND PROGRAMMING FOR DIGITAL/MOBILE: Antony Bruno (Denver) 303-771-1342 SENIOR CORRESPONDENTS: Ed Christman (Retail) 646-654-4723; Paul Heine (Radio) 646-654-4669; Kamau High (Branding) 646-654-5297; Gail Mitchell (R&B) 323-525-2289; Chuck Taylor (Pop) 646-654-4729; Tom Ferguson (Deputy Global Editor) 011-44-207-420-6069 CORRESPONDENTS: Ayala Ben-Yehuda (Latin) 323-525-2293; Mike Boyle (Rock) 646-654-4727; Hillary Crosley (R&B/Hip-Hop) 646-654-4647; Cortney Harding (Indies) 646-654-5592; Mitchell Peters 323-525-2322; Ken Tucker (Radio) 615-712-6639 INTERNATIONAL: Lars Brandle (Australia), Wolfgang Spahr (Germany), Robert Thompson (Canada) BILLBOARD.BIZ NEWS EDITOR: Chris M. Walsh 646-654-4904 Ticket Monster? GLOBAL NEWS EDITOR: Andre Paine 011-44-207-420-6068 BILLBOARD.COM EDITOR: Jessica Letkemann 646-654-5536 A Possible Live Nation-Ticketmaster Merger Could Hurt The Music Business -

YEAR-END 2019 RIAA U.S. LATIN MUSIC REVENUES REPORT Joshua P

YEAR-END 2019 RIAA U.S. LATIN MUSIC REVENUES REPORT Joshua P. Friedlander, Senior Vice President, Research and Economics Matthew Bass, Manager, Research “We at RIAA, together with the entire music community, are focused at this time on helping musicians, songwriters and others impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic. For anyone needing help, please visit the resources collected at MusicCovidRelief.com. Every spring, we release different metrics about the prior year’s music industry, including an annual report focused on Latin music. Because these numbers have long-term significance and value, we are releasing that report today. Our thoughts remain with everyone affected by the pandemic.” – Michele Ballantyne, Chief Operating Officer, RIAA As streaming has become the dominant format in Latin music in the U.S., it has driven the market to its highest level since 2006. Total revenues of $554 million were up 28%, growing at a faster rate than the overall U.S. music FIGURE 2 FIGURE market that was up 13% for the year. Streaming formats grew 32% to $529 million, comprising 95% of total Latin music revenues in 2019. In 2019, Latin music accounted for 5.0% of the total $11.1 billion U.S. recorded music business, an increase versus 4.4% in 2018. FIGURE 1 FIGURE Digital and customized radio revenues (including services like Pandora, SiriusXM, and Internet radio services) reversed 2018’s decline. Revenues from SoundExchange distributions and royalties from similar directly licensed services increased 18% to $64 million, accounting for 12% of streaming revenues. Unit based formats of Latin music continued to experience declining revenues. -

Dissertation

DISSERTATION Titel der Dissertation “We’re Punk as Fuck and Fuck like Punks:”* Queer-Feminist Counter-Cultures, Punk Music and the Anti-Social Turn in Queer Theory Verfasserin Mag.a Phil. Maria Katharina Wiedlack angestrebter akademischer Grad Doktorin der Philosophie (Dr. Phil.) Wien, Jänner 2013 Studienkennzahl lt. Studienblatt: A 092 343 Studienrichtung lt. Studienblatt: Anglistik und Amerikanistik Betreuerin / Betreuer: Univ. Prof.in Dr.in Astrid Fellner Earlier versions and parts of chapters One, Two, Three and Six have been published in the peer-reviewed online journal Transposition: the journal 3 (Musique et théorie queer) (2013), as well as in the anthologies Queering Paradigms III ed. by Liz Morrish and Kathleen O’Mara (2013); and Queering Paradigms II ed. by Mathew Ball and Burkard Scherer (2012); * The title “We’re punk as fuck and fuck like punks” is a line from the song Burn your Rainbow by the Canadian queer-feminist punk band the Skinjobs on their 2003 album with the same name (released by Agitprop Records). Content 1. Introduction .......................................................................................................... 1 2. “To Sir With Hate:” A Liminal History of Queer-Feminist Punk Rock ….………………………..…… 21 3. “We’re punk as fuck and fuck like punks:” Punk Rock, Queerness, and the Death Drive ………………………….………….. 69 4. “Challenge the System and Challenge Yourself:” Queer-Feminist Punk Rock’s Intersectional Politics and Anarchism……...……… 119 5. “There’s a Dyke in the Pit:” The Feminist Politics of Queer-Feminist Punk Rock……………..…………….. 157 6. “A Race Riot Did Happen!:” Queer Punks of Color Raising Their Voices ..……………..………… ………….. 207 7. “WE R LA FUCKEN RAZA SO DON’T EVEN FUCKEN DARE:” Anger, and the Politics of Jouissance ……….………………………….…………. -

Punk: Music, History, Sub/Culture Indicate If Seminar And/Or Writing II Course

MUSIC HISTORY 13 PAGE 1 of 14 MUSIC HISTORY 13 General Education Course Information Sheet Please submit this sheet for each proposed course Department & Course Number Music History 13 Course Title Punk: Music, History, Sub/Culture Indicate if Seminar and/or Writing II course 1 Check the recommended GE foundation area(s) and subgroups(s) for this course Foundations of the Arts and Humanities • Literary and Cultural Analysis • Philosophic and Linguistic Analysis • Visual and Performance Arts Analysis and Practice x Foundations of Society and Culture • Historical Analysis • Social Analysis x Foundations of Scientific Inquiry • Physical Science With Laboratory or Demonstration Component must be 5 units (or more) • Life Science With Laboratory or Demonstration Component must be 5 units (or more) 2. Briefly describe the rationale for assignment to foundation area(s) and subgroup(s) chosen. This course falls into social analysis and visual and performance arts analysis and practice because it shows how punk, as a subculture, has influenced alternative economic practices, led to political mobilization, and challenged social norms. This course situates the activity of listening to punk music in its broader cultural ideologies, such as the DIY (do-it-yourself) ideal, which includes nontraditional musical pedagogy and composition, cooperatively owned performance venues, and underground distribution and circulation practices. Students learn to analyze punk subculture as an alternative social formation and how punk productions confront and are times co-opted by capitalistic logic and normative economic, political and social arrangements. 3. "List faculty member(s) who will serve as instructor (give academic rank): Jessica Schwartz, Assistant Professor Do you intend to use graduate student instructors (TAs) in this course? Yes x No If yes, please indicate the number of TAs 2 4. -

IPG Spring 2020 Rock Pop and Jazz Titles

Rock, Pop, and Jazz Titles Spring 2020 {IPG} That Thin, Wild Mercury Sound Dylan, Nashville, and the Making of Blonde on Blonde Daryl Sanders Summary That Thin, Wild Mercury Sound is the definitive treatment of Bob Dylan’s magnum opus, Blonde on Blonde , not only providing the most extensive account of the sessions that produced the trailblazing album, but also setting the record straight on much of the misinformation that has surrounded the story of how the masterpiece came to be made. Including many new details and eyewitness accounts never before published, as well as keen insight into the Nashville cats who helped Dylan reach rare artistic heights, it explores the lasting impact of rock’s first double album. Based on exhaustive research and in-depth interviews with the producer, the session musicians, studio personnel, management personnel, and others, Daryl Sanders Chicago Review Press chronicles the road that took Dylan from New York to Nashville in search of “that thin, wild mercury sound.” 9781641602730 As Dylan told Playboy in 1978, the closest he ever came to capturing that sound was during the Blonde on Pub Date: 5/5/20 On Sale Date: 5/5/20 Blonde sessions, where the voice of a generation was backed by musicians of the highest order. $18.99 USD Discount Code: LON Contributor Bio Trade Paperback Daryl Sanders is a music journalist who has worked for music publications covering Nashville since 1976, 256 Pages including Hank , the Metro, Bone and the Nashville Musician . He has written about music for the Tennessean , 15 B&W Photos Insert Nashville Scene , City Paper (Nashville), and the East Nashvillian . -

Information and Secrecy in the Chicago DIY Punk Music Scene Kaitlin Beer University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee

University of Wisconsin Milwaukee UWM Digital Commons Theses and Dissertations December 2016 "It's My Job to Keep Punk Rock Elite": Information and Secrecy in the Chicago DIY Punk Music Scene Kaitlin Beer University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.uwm.edu/etd Part of the Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Beer, Kaitlin, ""It's My Job to Keep Punk Rock Elite": Information and Secrecy in the Chicago DIY Punk Music Scene" (2016). Theses and Dissertations. 1349. https://dc.uwm.edu/etd/1349 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by UWM Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UWM Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “IT’S MY JOB TO KEEP PUNK ROCK ELITE”: INFORMATION AND SECRECY IN THE CHICAGO DIY PUNK MUSIC SCENE by Kaitlin Beer A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Anthropology at The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee December 2016 ABSTRACT “IT’S MY JOB TO KEEP PUNK ROCK ELITE”: INFORMATION AND SECRECY IN THE CHICAGO DIY PUNK MUSIC SCENE by Kaitlin Beer The University of Wisconsin—Milwaukee, 2016 Under the Supervision of Professor W. Warner Wood This thesis examines how the DIY punk scene in Chicago has utilized secretive information dissemination practices to manage boundaries between itself and mainstream society. Research for this thesis started in 2013, following the North Atlantic Treaty Organization’s meeting in Chicago. This event caused a crisis within the Chicago DIY punk scene that primarily relied on residential spaces, from third story apartments to dirt-floored basements, as venues. -

4IOLWWOOD WALK of FAME Hollywood Walk of Fame Nomination

■>r 4IOLWWOOD WALK OF FAME Hollywood Walk Of Fame Nomination Selena Quintanllia-Perez mThe Queen off Tejano Music ns Before there was a JLo... Before there was a Shakira... Before there was a Beyonce... There was a transformative female artist called.... SELENA Selena was an American singer, songwriter, spokesperson actress, fashion designer and now a Legend, Her 'Ka* | contributions to music and fashion made her one of the most celebrated Mexican-American entertainers of the late 20th jj century. Her music, style, fashion and influence is as current today as when she was alive - a true institution for the ages. L Jp Billboardmagazine’s "top Latin artist of the ’90s", the "best selling Latin artist of the decade" and still charting today as A the 2016 Top Latin Album of the Year, Female Artist - her v legacy lives in her smile, music and family. While alive, she was regarded by the media and fans as the "Tejano Madonna" for her cutting edge clothing choices and dance moves. Today she ranks among the most influential 4I0IM00D Latin artists of all-time and is credited for catapulting the Texas WALK OF FAME sound into the mainstream market. The youngest child of the Quintanilla family, she debuted in the music scene in 1980 as the lead of the family band "Selena y Los Dinos” with her siblings A.B. Quintanilla and Suzette Quintanilla. Not only did she make record breaking music - but she broke all enty barriers of a male- dominated music scene. Her popularity exploded after she won the Female Vocalist of the Year in the 1986 Tejano Music Awards - a feat she would repeat nine consecutive years. -

The Long History of Indigenous Rock, Metal, and Punk

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Not All Killed by John Wayne: The Long History of Indigenous Rock, Metal, and Punk 1940s to the Present A thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in American Indian Studies by Kristen Le Amber Martinez 2019 © Copyright by Kristen Le Amber Martinez 2019 ABSTRACT OF THESIS Not All Killed by John Wayne: Indigenous Rock ‘n’ Roll, Metal, and Punk History 1940s to the Present by Kristen Le Amber Martinez Master of Arts in American Indian Studies University of California Los Angeles, 2019 Professor Maylei Blackwell, Chair In looking at the contribution of Indigenous punk and hard rock bands, there has been a long history of punk that started in Northern Arizona, as well as a current diverse scene in the Southwest ranging from punk, ska, metal, doom, sludge, blues, and black metal. Diné, Apache, Hopi, Pueblo, Gila, Yaqui, and O’odham bands are currently creating vast punk and metal music scenes. In this thesis, I argue that Native punk is not just a cultural movement, but a form of survivance. Bands utilize punk and their stories as a conduit to counteract issues of victimhood as well as challenge imposed mechanisms of settler colonialism, racism, misogyny, homophobia, notions of being fixed in the past, as well as bringing awareness to genocide and missing and murdered Indigenous women. Through D.I.Y. and space making, bands are writing music which ii resonates with them, and are utilizing their own venues, promotions, zines, unique fashion, and lyrics to tell their stories. -

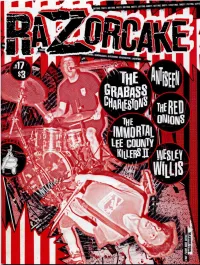

Razorcake Issue

PO Box 42129, Los Angeles, CA 90042 #17 www.razorcake.com It’s strange the things you learn about yourself when you travel, I took my second trip to go to the wedding of an old friend, andI the last two trips I took taught me a lot about why I spend so Tommy. Tommy and I have been hanging out together since we much time working on this toilet topper that you’re reading right were about four years old, and we’ve been listening to punk rock now. together since before a lot of Razorcake readers were born. Tommy The first trip was the Perpetual Motion Roadshow, an came to pick me up from jail when I got arrested for being a smart independent writers touring circuit that took me through seven ass. I dragged the best man out of Tommy’s wedding after the best cities in eight days. One of those cities was Cleveland. While I was man dropped his pants at the bar. Friendships like this don’t come there, I scammed my way into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. See, along every day. they let touring bands in for free, and I knew this, so I masqueraded Before the wedding, we had the obligatory bachelor party, as the drummer for the all-girl Canadian punk band Sophomore which led to the obligatory visit to the strip bar, which led to the Level Psychology. My facial hair didn’t give me away. Nor did my obligatory bachelor on stage, drunk and dancing with strippers. -

Rock Music and Representation: the Roles of Rock Culture AMS 311S // Unique No

Page 1 Rock Music and Representation: The Roles of Rock Culture AMS 311s // Unique No. 31080 Spring 2020 BUR 436A: M/W/F 11:00 am – 12:00 pm Instructor: Kate Grover // [email protected] // pronouns: she, her, hers Office Hours: BUR 408 // Monday & Wednesday, 1 pm – 2:30 pm, or by appointment Course Description What is a guitar god? Who gets to be one, and why? What are the “roles” of rock music and culture? What is rock, anyway? This is not your average rock history course. Instead, this course positions 20th and 21st century American rock music and culture as a crucial site for ongoing struggles over identity, belonging, and power. We will explore how race, class, gender, sexuality, age, and ability have shaped how various groups of people engage with rock and what insights these engagements provide about “the American experience” over time. How do rock artists, critics, filmmakers, and fans represent themselves and others? What do these representational strategies reveal about inclusion and exclusion in rock culture, and in American society at large? While examining rock’s players, we will also consider the roles of different rock media and institutions such as MTV, the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, and Rolling Stone magazine. As such, our course is divided into three units exploring different areas of representation within rock music and culture. Unit 1: Performing Rock, Performing Identity, provides an introduction to studying rock’s sounds, visuals, and texts by investigating various issues of identity within rock music and culture. Unit 2: Evaluating Rock: Writers, Critics, and Other Commentators focuses on the roles of rock critics and the stakes of writing about music. -

EASTSIDE PUNKS a Screening and Conversation Thursday, April 22, 2021, at 7 P.M

THEMEGUIDE EASTSIDE PUNKS A Screening and Conversation Thursday, April 22, 2021, at 7 p.m. Live via Zoom University of Southern California WHAT TO KNOW o Eastside Punks is a series of documentary shorts produced by Razorcake magazine about the first generation of East L.A. punk, circa the late 1970s and early ’80s o This event includes excerpts from Eastside Punks and a panel discussion with members of several of the featured bands: Thee Undertakers, The Brat, and the Stains o Razorcake is an L.A.-based DIY punk zine Photo: Angie Garcia ABOUT THE PARTICIPANTS Jimmy Alvarado (Eastside Punks director) has been active in East L.A.’s underground music scene since 1981 as a musician, backyard gig promoter, writer, poet, bouncer, flyer artist, photographer, podcaster, historian, and filmmaker. He has authored numerous interviews, articles, and short films spotlighting the Eastside scene. He plays guitar in the bands La Tuya and Our Band Sucks. Teresa Covarrubias was the vocalist for The Brat. Their debut EP, Attitudes, was released on The Plugz’ record label, featured contributions from John Doe and Exene from X, and is a prized item among collectors. Straight Outta East L.A., a double Photo: Edward Colver album packaging it with other rare tracks, was released in 2017. Tracy “Skull” Garcia was the bass player of Thee Undertakers. Starting off by playing local parties in 1977, they became regulars in the scene centered around the Vex. Their 1981 debut album, Crucify Me, successfully melded second-wave hardcore bite with first-wave art sensibilities, but wasn’t released until 2001 on CD and 2020 on vinyl. -

Punk Rock and the Socio-Politics of Place Dissertation Presented

Building a Better Tomorrow: Punk Rock and the Socio-Politics of Place Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University by Jeffrey Samuel Debies-Carl Graduate Program in Sociology The Ohio State University 2009 Dissertation Committee: Townsand Price-Spratlen, Advisor J. Craig Jenkins Amy Shuman Jared Gardner Copyright by Jeffrey S. Debies-Carl 2009 Abstract Every social group must establish a unique place or set of places with which to facilitate and perpetuate its way of life and social organization. However, not all groups have an equal ability to do so. Rather, much of the physical environment is designed to facilitate the needs of the economy—the needs of exchange and capital accumulation— and is not as well suited to meet the needs of people who must live in it, nor for those whose needs are otherwise at odds with this dominant spatial order. Using punk subculture as a case study, this dissertation investigates how an unconventional and marginalized group strives to manage ‘place’ in order to maintain its survival and to facilitate its way of life despite being positioned in a relatively incompatible social and physical environment. To understand the importance of ‘place’—a physical location that is also attributed with meaning—the dissertation first explores the characteristics and concerns of punk subculture. Contrary to much previous research that focuses on music, style, and self-indulgence, what emerged from the data was that punk is most adequately described in terms of a general set of concerns and collective interests: individualism, community, egalitarianism, antiauthoritarianism, and a do-it-yourself ethic.