“Standardization of Cultural Products in Latin Pop-Music”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Before the Body by Lauren Espinoza a Practicum Presented in Partial

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by ASU Digital Repository Before the Body by Lauren Espinoza A Practicum Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Fine Arts Approved April 2015 by the Graduate Supervisory Committee: Alberto Ríos, Chair Cynthia Hogue Sara Ball ARIZONA STATE UNIVERSITY May 2015 ABSTRACT Set in South Texas, the poems of “Before the Body” address the border, not of place, but in between people. Following a narrative arc from a grandfather who spoke another language—silence—to a young boy who drowns in silence, these poems are expressions of the speaker’s search for intimacy in language: what words intend themselves to be, what language means to be. i DEDICATION This book is dedicated to honoring the memory of Rosa Espinoza, Refugio Espinoza, Clementina Smith Garza, Ruby Delgado, and Jose Flores, Jr; and for the Espinozas and Garzas that are not memory, but present—gracias for your voices and your support. Thank you to my professors and friends who have spken to me (at length) about the form and content behind these poems: Casie Moreland, Sara Sams, Michele Poulos, Bryan Asdel, Lauren Albin, Lakshami Mahajan, Chandra Narcia, Monica Teresa Ortiz, and Laurie Ann Guerrero. Para mis profesores, nunca pudria hacer esto sin ustedes: Alberto Ríos, Sally Ball, Cynthia Hogue, Carmen Gimenez Smith, and Deborah Paredez. To Yazmin, si tuviera cuatro vidas, cuatro vidas serian para ti—estas poemas son una vida. And finally, muchísimas gracias to my parents, thank you for believing in me throughout the years—it is your strength that has given me everything. -

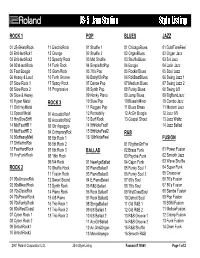

PTSVNWU JS-5 Jam Station Style Listing

PTSVNWU JS-5 Jam Station Style Listing ROCK 1 POP BLUES JAZZ 01 JS-5HardRock 11 ElectricRock 01 Shuffle 1 01 ChicagoBlues 01 DublTimeFeel 02 BritHardRck1 12 Grunge 02 Shuffle 2 02 OrganBlues 02 Organ Jazz 03 BritHardRck2 13 Speedy Rock 03 Mid Shuffle 03 ShuffleBlues 03 5/4 Jazz 04 80'sHardRock 14 Funk Rock 04 Simple8btPop 04 Boogie 04 Latin Jazz 05 Fast Boogie 15 Glam Rock 05 70's Pop 05 Rockin'Blues 05 Soul Jazz 06 Heavy & Loud 16 Funk Groove 06 Early80'sPop 06 RckBeatBlues 06 Swing Jazz 1 07 Slow Rock 1 17 Spacy Rock 07 Dance Pop 07 Medium Blues 07 Swing Jazz 2 08 Slow Rock 2 18 Progressive 08 Synth Pop 08 Funky Blues 08 Swing 6/8 09 Slow & Heavy 09 Honky Piano 09 Jump Blues 09 BigBandJazz 10 Hyper Metal ROCK 3 10 Slow Pop 10 BluesInMinor 10 Combo Jazz 11 Old HvyMetal 11 Reggae Pop 11 Blues Brass 11 Modern Jazz 12 Speed Metal 01 AcousticRck1 12 Rockabilly 12 AcGtr Boogie 12 Jazz 6/8 13 HvySlowShffl 02 AcousticRck2 13 Surf Rock 13 Gospel Shout 13 Jazz Waltz 14 MidFastHR 1 03 Gtr Arpeggio 14 8thNoteFeel1 14 Jazz Ballad 15 MidFastHR 2 04 CntmpraryRck 15 8thNoteFeel2 R&B 16 80sHeavyMetl 05 8bt Rock 1 16 16thNoteFeel FUSION 17 ShffleHrdRck 06 8bt Rock 2 01 RhythmGtrFnk 18 FastHardRock 07 8bt Rock 3 BALLAD 02 Brass Funk 01 Power Fusion 19 HvyFunkRock 08 16bt Rock 03 Psyche-Funk 02 Smooth Jazz 09 5/4 Rock 01 NewAgeBallad 04 Cajun Funk 03 Wave Shuffle ROCK 2 10 Shuffle Rock 02 PianoBallad1 05 Funky Soul 1 04 Super Funk 11 Fusion Rock 03 PianoBallad2 06 Funky Soul 2 05 Crossover 01 90sGrooveRck 12 Sweet Sound 04 E.PianoBalad 07 60's Soul 06 -

Selena Live the Last Concert Album Download Live: the Last Concert

selena live the last concert album download Live: The Last Concert. Selena's charismatic personality and talent are captured throughout Live: The Last Concert, recorded in Houston, TX, on February 26, 1995, about a month before her tragic death (the Tex-Mex queen was murdered on March 31, 1995, at the age of 23). This record opens with a disco medley, including the classics "I Will Survive," "Funky Town," "The Hustle," and "On the Radio." It features a catchy mid-tempo "Bidi Bidi Bom Bom," the bolero-inflected "No Me Queda Mas," the Latin pop number "Cobarde," and the electronica-meets-tropical style of "Techno Cumbia," along with the Cumbia and Tejano hits "Amor Prohibido," "La Carcacha," "Baila Esta Cumbia," and "El Chico del Apt. 512." The set ends with a romantic and seductive "Como la Flor." Live : The Last Concert is a good opportunity to enjoy Selena's legacy. Discografia Selena Quintanilla y Los Dinos MEGA Completa [58CDs] Descargar Discografia Selena Quintanilla Mega cantante estadounidense de raíces mexicanas , del género Cumbia Ranchera , Tex-Mex y Pop Latino , nació el 16 de abril de 1971 en la ciudad de Lake Jackson, Texas, Estados Unidos. Es considerada una de las principales exponentes de la música latina. Descargar Discografia Selena Quintanilla Mega Completa. En su trayectoria musical la reina del tex-mex logro vender mas de 60 millones de discos en el mundo y 5 de sus álbumes de estudio fueron nominados a la lista de los Billboard 200 . Selena murió asesinada el 31 de marzo de 1995 a la edad de 23 años a manos de Yolanda Saldívar que era presidente del club de fans y administradora de sus boutiques. -

Ticket Monster?

004BILB06.QXP 2/5/09 6:52 PM Page 1 PUBLISHER HOWARD APPELBAUM EDITORIAL DIRECTOR BILL WERDE EDITORIAL EXECUTIVE EDITOR: ROBERT LEVINE 646-654-4707 DEPUTY EDITOR: Louis Hau 646-654-4708 SENIOR EDITORS: Jonathan Cohen 646-654-5582; Ann Donahue 323-525-2292 SPECIAL FEATURES EDITOR: Thom Duffy 646-654-4716 EDITORIALS | COMMENTARY | LETTERS INTERNATIONAL BUREAU CHIEF: Mark Sutherland 011-44-207-420-6155 OPINION EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR OF CONTENT AND PROGRAMMING FOR LATIN MUSIC AND ENTERTAINMENT: Leila Cobo (Miami) 305-361-5279 EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR OF CONTENT AND PROGRAMMING FOR TOURING AND LIVE ENTERTAINMENT: Ray Waddell (Nashville) 615-431-0441 EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR OF CONTENT AND PROGRAMMING FOR DIGITAL/MOBILE: Antony Bruno (Denver) 303-771-1342 SENIOR CORRESPONDENTS: Ed Christman (Retail) 646-654-4723; Paul Heine (Radio) 646-654-4669; Kamau High (Branding) 646-654-5297; Gail Mitchell (R&B) 323-525-2289; Chuck Taylor (Pop) 646-654-4729; Tom Ferguson (Deputy Global Editor) 011-44-207-420-6069 CORRESPONDENTS: Ayala Ben-Yehuda (Latin) 323-525-2293; Mike Boyle (Rock) 646-654-4727; Hillary Crosley (R&B/Hip-Hop) 646-654-4647; Cortney Harding (Indies) 646-654-5592; Mitchell Peters 323-525-2322; Ken Tucker (Radio) 615-712-6639 INTERNATIONAL: Lars Brandle (Australia), Wolfgang Spahr (Germany), Robert Thompson (Canada) BILLBOARD.BIZ NEWS EDITOR: Chris M. Walsh 646-654-4904 Ticket Monster? GLOBAL NEWS EDITOR: Andre Paine 011-44-207-420-6068 BILLBOARD.COM EDITOR: Jessica Letkemann 646-654-5536 A Possible Live Nation-Ticketmaster Merger Could Hurt The Music Business -

YEAR-END 2019 RIAA U.S. LATIN MUSIC REVENUES REPORT Joshua P

YEAR-END 2019 RIAA U.S. LATIN MUSIC REVENUES REPORT Joshua P. Friedlander, Senior Vice President, Research and Economics Matthew Bass, Manager, Research “We at RIAA, together with the entire music community, are focused at this time on helping musicians, songwriters and others impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic. For anyone needing help, please visit the resources collected at MusicCovidRelief.com. Every spring, we release different metrics about the prior year’s music industry, including an annual report focused on Latin music. Because these numbers have long-term significance and value, we are releasing that report today. Our thoughts remain with everyone affected by the pandemic.” – Michele Ballantyne, Chief Operating Officer, RIAA As streaming has become the dominant format in Latin music in the U.S., it has driven the market to its highest level since 2006. Total revenues of $554 million were up 28%, growing at a faster rate than the overall U.S. music FIGURE 2 FIGURE market that was up 13% for the year. Streaming formats grew 32% to $529 million, comprising 95% of total Latin music revenues in 2019. In 2019, Latin music accounted for 5.0% of the total $11.1 billion U.S. recorded music business, an increase versus 4.4% in 2018. FIGURE 1 FIGURE Digital and customized radio revenues (including services like Pandora, SiriusXM, and Internet radio services) reversed 2018’s decline. Revenues from SoundExchange distributions and royalties from similar directly licensed services increased 18% to $64 million, accounting for 12% of streaming revenues. Unit based formats of Latin music continued to experience declining revenues. -

Rhythm Is Gonna Get You”-- Gloria Estefan and the Miami Sound Machine (1987) Added to the National Registry: 2017 Essay by Ilan Stavans (Guest Post)*

“Rhythm Is Gonna Get You”-- Gloria Estefan and the Miami Sound Machine (1987) Added to the National Registry: 2017 Essay by Ilan Stavans (guest post)* “Let It Loose” album cover 45rpm single Enrique Garcia Gloria Estefan’s “Rhythm Is Gonna Get You,” which represents the apex of Cuban influence on American R&B, also serves as a thermometer for Latino assimilation to the United States, especially in Miami, which was always Estefan’s base. The song came about shortly before her bus accident in 1990, as she was touring, an event that marked her profoundly, physically and creatively. As such, it represents her “early” style and approach, in comparison with a later period in which Estefan would invoke her Cuban roots and upbringing in more concrete fashion. Along with “Conga,” “Bad Boy,” “Get on Your Feet,” “Party Time,” and about half a dozen more, the song made Estefan internationally known. Performed together with Estefan’s group, Miami Sound Machine, founded by her husband Emilio Estefan, it is part of the immensely successful album “Let It Loose” (1987), which went multi-platinum. The song itself was Top 5 on the US Billboard Top 100. It came to define R&B and become a staple of the post-disco disco era because of its eminently danceable qualities. Indeed, most people associate it with an Americanized version of Latin twirl. Estefan is originally from Havana (she was born in 1957). She and her family—her father was a motor escort for dictator Fulgencio Batista’s wife—were part of a massive wave of mostly upper- and middle-class Cubans who moved to the United States in the 1960s, absconding Fidel Castro’s Communist regime. -

On the Charts

ON THE CHARTS The chart recaps in this Latin music spe- Ht T,a,ti n un s T(» Latin cial are year -to -date starting with the Dec. 3, 2005, issue, the beginning of the chart Pos. TITLE -Artist Imprint/Label year, through the April 1, 2006, issue. 1 ROMPE Daddy Yankee Pos. DISTRIBUTOR (Na Charted Titles) Recaps for Top Latin Albums are based 2 ELLA Y YO Aventura Featuring 1 UNIVERSAL (11O) on sales information compiled by Nielsen Don Omar 2 SONY BMG (39) SoundScan. Recaps for Hot Latin Songs 3 RAKATA Wisin & Yandel 3 EMM (10) are based on gross audience impressions 4 LLAME PA' VERTE Wisin & Yandel 4 INDEPENDENTS (13) from airplay monitored by Nielsen BDS. Ti- 5 VEN BAILALO Angel & Khriz 5 WEA (4) tles receive credit for sales or audience im- 6 MAYOR QUE YO Baby Ranks, pressions accumulated during each week Daddy Yankee, Tonny Tun Tun, Wisin, rh)I) Latin they appear on the pertinent chart. Yandel & Hector 7 CUENTALE Ivy Queen Recaps compiled by rock charts manager 8 NA NA NA (DULCE NINA) Pos. IMPRINT (Na Charted Titles) Anthony Colombo with assistance from A.B. Quintanilla III Presents 1 SONY BMG NORTE (33) Latin charts manager Ricardo Companioni. Kumbia Kings 2 EMI LATIN (8) 9 CONTRA VIENTO Y MAREA 3 EL CARTEL (2) mio Billboard, Flaco Jiménez is inducted into Intocable 4 DISA í77) the Hall of Fame, and Olga Tañón receives the 10 ESO EHH II Alexis & Fido 5 FONOVISA (25) I1O1 Latin ( (If' í\rtisls Spirit of Hope award. 11 LA TORTURA Memorably, Ricky Martin performs "Livin' Pos. -

052019.Log ********** 88.5 Fm Keom 05/20/19

052019.LOG ********** 88.5 FM KEOM 05/20/19 EST.TIME YEAR TITLE ARTIST 12:00 A Rock Me Amadeus Falco 12:03 A 74 I'm Leaving It All Up To You Donny & Marie Osmond 12:05 A 72 Me And Mrs. Jones Billy Paul 12:10 A 83 You Are Lionel Richie 12:14 A 82 Do You Really Want To Hurt Me Culture Club 12:16 A 71 Beginnings (Short Version) Chicago 12:19 A 75 Jive Talkin' Bee Gees 12:22 A 74 Everlasting Love Carl Carlton 12:24 A 76 (Shake Shake Shake) Shake Your Boot KC & The Sunshine Band 12:31 A 96 Change The World Eric Clapton 12:35 A 82 Who Can It Be Now Men At Work 12:38 A 84 To All The Girls I've Loved Before Julio Iglesias & Willie Nelson 12:41 A 91 Coming Out Of The Dark Gloria Estefan 12:46 A 79 Goodnight Tonight Paul McCartney [+] Wings 12:50 A 72 I Am Woman Helen Reddy 12:53 A 76 Muskrat Love Captain & Tennille ********** 88.5 FM KEOM 05/20/19 EST.TIME YEAR TITLE ARTIST 01:00 A 75 Calypso John Denver 01:03 A 77 You Make Lovin' Fun Fleetwood Mac 01:06 A 70 Signed, Sealed, Delivered I'm Yours Stevie Wonder Page 1 052019.LOG 01:09 A 82 You Can't Hurry Love Phil Collins 01:12 A 71 Maggie May Rod Stewart 01:16 A 77 I Feel Love Donna Summer 01:21 A 84 Magic Cars 01:25 A 70 (They Long To Be) Close To You Carpenters 01:29 A Show Me Love Robyn 01:31 A 83 Girls Just Want To Have Fun Cyndi Lauper 01:35 A 77 Lovely Day Bill Withers 01:39 A 99 Bailiamos Enrique Iglesias 01:42 A 75 Heat Wave Linda Ronstadt 01:46 A 72 Rockin' Robin Michael Jackson 01:48 A 75 Swearin' To God Frankie Valli ********** 88.5 FM KEOM 05/20/19 EST.TIME YEAR TITLE ARTIST 02:00 A -

Background Music

BACKGROUND MUSIC GET THE BEST MUSIC ALL DAY LONG TouchTunes’ music programmers are passionate about music. They create a variety of fully licensed background music channels for TouchTunes locations to choose from. From Classic Rock and The Hits to Decades Variety and Holiday Mix, TouchTunes jukeboxes are designed to keep the party going all night long while still allowing patrons to make their own song selections. HIGHLIGHTS • Fully licensed for commercial establishments • Over 20 themed music channels to choose from • Each channel features over 30 hours of music • Refreshed monthly with new music • Channels can be changed instantly using the jukebox remote • Can be scheduled for a specific time of the day or all day long LITCMP V.032016 BACKGROUND MUSIC ADULT CONTEMPORARY REGGAE Easy light favorites from the ‘90s to today. Classic jams from Reggae legends. ALTERNATIVE ROCK THE HITS A diverse selection of alternative rock songs. A mix of current and mainstream hits across all genres. BLUES URBAN & HIP HOP A contemporary collection of blues artists. A contemporary mix of urban and hip-hop songs. CLASSIC R&B & SOUL ROCK MIX Sounds from the pioneers of R&B and Soul. The ultimate rock selection featuring timeless rock songs from CLASSIC ROCK the past 30 years. Rock’s biggest bands and timeless hits. DECADES VARIETY COUNTRY MIX Great songs by great artists from the 70’s to today. Mid-tempo mix of country music from the last 30 years. LATIN MIX EASY LISTENING A mix of Latin styles including Regional Mexican, Pop Rock, Lite pop and rock hits from the ‘80s, ‘90s and today. -

Spanglish Code-Switching in Latin Pop Music: Functions of English and Audience Reception

Spanglish code-switching in Latin pop music: functions of English and audience reception A corpus and questionnaire study Magdalena Jade Monteagudo Master’s thesis in English Language - ENG4191 Department of Literature, Area Studies and European Languages UNIVERSITY OF OSLO Spring 2020 II Spanglish code-switching in Latin pop music: functions of English and audience reception A corpus and questionnaire study Magdalena Jade Monteagudo Master’s thesis in English Language - ENG4191 Department of Literature, Area Studies and European Languages UNIVERSITY OF OSLO Spring 2020 © Magdalena Jade Monteagudo 2020 Spanglish code-switching in Latin pop music: functions of English and audience reception Magdalena Jade Monteagudo http://www.duo.uio.no/ Trykk: Reprosentralen, Universitetet i Oslo IV Abstract The concept of code-switching (the use of two languages in the same unit of discourse) has been studied in the context of music for a variety of language pairings. The majority of these studies have focused on the interaction between a local language and a non-local language. In this project, I propose an analysis of the mixture of two world languages (Spanish and English), which can be categorised as both local and non-local. I do this through the analysis of the enormously successful reggaeton genre, which is characterised by its use of Spanglish. I used two data types to inform my research: a corpus of code-switching instances in top 20 reggaeton songs, and a questionnaire on attitudes towards Spanglish in general and in music. I collected 200 answers to the questionnaire – half from American English-speakers, and the other half from Spanish-speaking Hispanics of various nationalities. -

Heritage Month

HARRIS BEACH RECOGNIZES NATIONAL HISPANIC HERITAGE MONTH National Hispanic Heritage Month in the United States honors the histories, cultures and contributions of American citizens whose ancestors came from Spain, Mexico, the Caribbean and Central and South America. We’re participating at Harris Beach by spotlighting interesting Hispanic public figures, and facts about different countries, and testing your language skills. As our focus on National Hispanic Heritage Month continues, this week we focus on a figure from the world of sports: Roberto Clemente, who is known as much for his accomplishments as humanitarian as he is for his feats on the field of play. ROBERTO CLEMENTE Roberto Enrique Clemente Walker of Puerto Rico, born August 18, 1934, has the distinction of being the first Latin American and Caribbean player to be inducted in the National Baseball Hall of Fame. He played right field over 18 seasons for the Pittsburgh Pirates. Clemente’s untimely death established the precedent that, as an alternative to the five-year retirement period, a player who has been deceased for at least six months is eligible for entry into the Hall of Fame. Clemente was the youngest of 7 children and was raised in Barrio San Antón, Carolina, Puerto Rico. During his childhood, his father worked as foreman of sugar crops located in the municipality and, because the family’s resources were limited, Clemente worked alongside his father in the fields by loading and unloading trucks. Clemente was a track and field star and Olympic hopeful before deciding to turn his full attention to baseball. His interest in baseball showed itself early on in childhood with Clemente often times playing against neighboring barrios. -

II. World Popular Music Several Interrelated Developments

II. World popular music Several interrelated developments in global culture since the latter 1900s have had a substantial effect on world popular music and its study. These include the phenomenal increase in the amount of recorded popular music outside the developed world, as a result of the expansion of extant modes of musical production and dissemination and the advent of new technologies such as cassettes, CDs, video compact discs, and the Internet; the effective compression of the world by intensified media networks, transport facilities, diasporas, and the globalization of capital, which has increased the transnational circulation of world popular musics and their availability in the West; and an exponential growth from the 1990s in the number of scholarly and journalistic studies of world popular musics. Some of the major conceptual approaches that have informed modern scholarly studies of world popular musics are reviewed in the following sections. The term ‘popular music’ is used here to connote genres whose styles have evolved in an inextricable relationship with their dissemination via the mass media and their marketing and sale on a mass-commodity basis. Distinctions between popular musics (defined thus) and other kinds of music, such as commercialized versions of folk musics, are not always airtight. The scope of the present section of this article is limited to popular music idioms that are stylistically distinct from those of the Euro-American mainstream. The significant role that Euro-American popular music styles play in many non-Western music cultures is discussed only tangentially here, and is addressed more specifically in POP, §V. There is at present no satisfactory label for popular musics outside the Euro-American mainstream (just as designations such as the ‘third world’ or even the ‘developing world’ are increasingly problematic).