Yield Variations of Some Common Wild Berries in Finland in 1956–1996

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Week Five: Indigenous Food Focus Salmonberry/Cloudberry Day!!

Farm to School Month – Week Five: Indigenous Food Focus Salmonberry/Cloudberry Day!! Many thanks go out to Melissa Chlupach, Regional Healthcare Dietitian with NANA Management Services, for all her help with all the information she has provided me for each Wednesday this month celebrating Indigenous Foods We Eat! All information I have listed below is based on the materials she has passed along. Thank you, Melissa!! SALMONBERRY/CLOUDBERRY Let’s learn about salmonberries and cloudberries today!! Why take a whole day to look at these two berries? Well, whether you are in Southcentral, the Kenai, or the Southeast Alaska and pick high bush salmonberries or live in Northern or Western Alaska and pick low bush salmonberries (cloudberries), you know how healthy and delicious these little berries can be!! The Roots of Salmonberry/Cloudberry History • Both of these berries are members of the rose (Rosaceae) family and one or the other is found all around Alaska. • Even though the some of the colors and shape of these berries are similar and they are in the same family, these two berries grow and taste very different. • All Alaska wild berries, have high levels of antioxidants. Antioxidants are a group of physiologically active compounds that work to neutralize free radicals (molecules with unpaired electrons). • Historical references document early use of cloudberries to prevent and treat scurvy as well as the medicinal use of the roots and leaves of the plant. • Both berries are considered an important food of the Alaska Native people as sources rich in vitamins A and C. Let’s Move into the Science of Salmonberries and Cloudberries Pronunciation: ˈsæmənˌbɛri and klaʊd ˌbɛri Yup’ik name: atsalugpiaq Iñupiaq name: aqpik Sugt’stun name: alagnaq aqagwik Unangam Tunuu name: alagnan algnan Tlingit name: was’x’aan tléigu néx’w Family: Rosaceae (both) Genus: Rubus (both) Species: R. -

Foraging in Boreal Forest: Wild Food Plants of the Republic of Karelia, NW Russia

foods Article Foraging in Boreal Forest: Wild Food Plants of the Republic of Karelia, NW Russia Valeria Kolosova 1,2, Olga Belichenko 1,* , Alexandra Rodionova 3 , Denis Melnikov 4 and Renata Sõukand 1,* 1 Department of Environmental Sciences, Informatics and Statistics, Ca’ Foscari University of Venice, Via Torino 155, 30172 Venice, Italy; [email protected] 2 Institute for Linguistic Studies, Russian Academy of Sciences, Tuchkov pereulok 9, 199004 St Petersburg, Russia 3 Institute of Linguistics, Literature and History of the Karelian Research Centre, Russian Academy of Sciences, Pushkinskaya St. 11, 185910 Petrozavodsk, Russia; [email protected] 4 Komarov Botanical Institute, Russian Academy of Sciences, Professor Popov St. 2, 197376 St Petersburg, Russia; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] (O.B.); [email protected] (R.S.) Received: 4 July 2020; Accepted: 27 July 2020; Published: 29 July 2020 Abstract: While the current consumption of wild food plants in the taiga of the American continent is a relatively well-researched phenomenon, the European taiga area is heavily underrepresented in the scientific literature. The region is important due to its distinctive ecological conditions with restricted seasonal availability of wild plants. During an ethnobotanical field study conducted in 2018–2019, 73 people from ten settlements in the Republic of Karelia were interviewed. In addition, we conducted historical data analysis and ethnographical source analysis. The most widely consumed wild food plants are forest berries (three Vaccinium species, and Rubus chamaemorus), sap-yielding Betula and acidic Rumex. While throughout the lifetime of the interviewees the list of used plants did not change considerably, the ways in which they are processed and stored underwent several stages in function of centrally available goods, people’s welfare, technical progress, and ideas about the harm and benefit of various products and technological processes. -

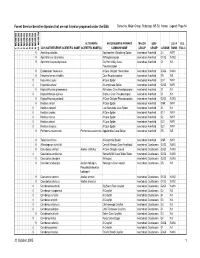

Sensitive Species That Are Not Listed Or Proposed Under the ESA Sorted By: Major Group, Subgroup, NS Sci

Forest Service Sensitive Species that are not listed or proposed under the ESA Sorted by: Major Group, Subgroup, NS Sci. Name; Legend: Page 94 REGION 10 REGION 1 REGION 2 REGION 3 REGION 4 REGION 5 REGION 6 REGION 8 REGION 9 ALTERNATE NATURESERVE PRIMARY MAJOR SUB- U.S. N U.S. 2005 NATURESERVE SCIENTIFIC NAME SCIENTIFIC NAME(S) COMMON NAME GROUP GROUP G RANK RANK ESA C 9 Anahita punctulata Southeastern Wandering Spider Invertebrate Arachnid G4 NNR 9 Apochthonius indianensis A Pseudoscorpion Invertebrate Arachnid G1G2 N1N2 9 Apochthonius paucispinosus Dry Fork Valley Cave Invertebrate Arachnid G1 N1 Pseudoscorpion 9 Erebomaster flavescens A Cave Obligate Harvestman Invertebrate Arachnid G3G4 N3N4 9 Hesperochernes mirabilis Cave Psuedoscorpion Invertebrate Arachnid G5 N5 8 Hypochilus coylei A Cave Spider Invertebrate Arachnid G3? NNR 8 Hypochilus sheari A Lampshade Spider Invertebrate Arachnid G2G3 NNR 9 Kleptochthonius griseomanus An Indiana Cave Pseudoscorpion Invertebrate Arachnid G1 N1 8 Kleptochthonius orpheus Orpheus Cave Pseudoscorpion Invertebrate Arachnid G1 N1 9 Kleptochthonius packardi A Cave Obligate Pseudoscorpion Invertebrate Arachnid G2G3 N2N3 9 Nesticus carteri A Cave Spider Invertebrate Arachnid GNR NNR 8 Nesticus cooperi Lost Nantahala Cave Spider Invertebrate Arachnid G1 N1 8 Nesticus crosbyi A Cave Spider Invertebrate Arachnid G1? NNR 8 Nesticus mimus A Cave Spider Invertebrate Arachnid G2 NNR 8 Nesticus sheari A Cave Spider Invertebrate Arachnid G2? NNR 8 Nesticus silvanus A Cave Spider Invertebrate Arachnid G2? NNR -

The Ethnoecology and Reproductive Ecology of Bakeapple (Rubus Chamaemorus L., Rosaceae) in Southern Labrador

The ethnoecology and reproductive ecology of bakeapple (Rubus chamaemorus L., Rosaceae) in southern Labrador Amanda Karst B.Sc., University of Regina, 2002 A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE in the Department of Biology O Amanda Karst, 2005 University of Victoria All rights reserved. This thesis may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy of other means, without the permission of the author Co-supervisors Dr. Nancy J. Turner and Dr. Gerry Allen ABSTRACT Bakeapple (Rubus chamaemovus L.; Rosaceae) is a circumpolar herbaceous perennial typically found in peat bogs. Bakeapple fruits have served as a vital food - resource for many northern peoples including those of the Subarctic and Arctic areas of North America. Although the reproductive ecology and habitat requirements of this plant have been studied extensively in Scandinavia, there has been scant research on bakeapple populations in Canada. Furthermore, there has been little documentation of its use or ethnoecology in many parts of Canada, especially in Newfoundland and Labrador. For this research I worked in the predominantly Metis community of Charlottetown, Labrador, where there has been a long tradition of bakeapple use. My objectives were to: 1. Document traditional use and major changes in use of bakeapple by this community; 2. Determine the most important factors influencing fruit production in local bakeapple populations; and 3. Link community observations on the ecology of this species with previous research and ecological data from my study in the area. To examine traditional use and knowledge of bakeapple in the community of Charlottetown, I conducted semi-directed in-depth interviews with knowledgeable bakeapple pickers in the community. -

Cairngorms Wild Plants Keys Mountains

Unlock the outdoors Cairngorms wild plants keys Mountains An outdoor learning resource for group leaders KEYS to Cairngorms mountains Key The language of the Cairngorms 1 Gaelic and Scots words for plants and places Key Lines on the landscape 2 Poems and prose to inspire us Key The shaping of our mountains 3 Cairngorms geology and erosion Key Natural treelines 4 In search of ‘krummholz’ Key Patterns in the heather moors 5 Red grouse and the landscape of muirburn Key Blanket bogs 6 Sphagnum mosses and peat hags Key A splash of spring green 7 Spring lines and flushes Key Life in the snow and ice 8 Explore the arctic alpine world of Scotland Key What’s that plant? 9 Spotter guides with handy plant ID tips Cairngorms mountains keys | Contents Unlocking Cairngorms mountains How to use the KEYS Each KEY includes an ‘Idea’ and short ‘Activity’, with a ‘Discussion’ The KEYS explore different section to take things further. You aspects of Cairngorms mountain don’t need to know the answers to habitats and wildlife and are a the questions, they are prompts to learning resource for leaders. stimulate thought and discussion. Whether hill walking, climbing Have fun with them. Choose KEYS or wildlife watching, there will to suit your group. Fit the KEYS into be something in the KEYS for short stops or lunch breaks with you to help enrich your group’s your group. Or take more time and experience of this amazing habitat. unlock more of the Cairngorms. ©Gwenda Diack Cairngorms mountains keys | Introduction Cairngorms mountains Important Plant Areas are the fascinating flora which is one most important places in the of the reasons why Plantlife world for wild plant and fungal identified the Cairngorms as diversity that can be protected an Important Plant Area (IPA). -

Värdväxtbyte Hos Myrvisslaren, Pyrgus Centaureae (Lepidoptera: Hesperiidae)

Ent. Tidskr. 133 (2012) Värdväxtbyte hos myrvisslaren, Pyrgus centaureae Värdväxtbyte hos myrvisslaren, Pyrgus centaureae (Lepidoptera: Hesperiidae) PEr-OlOf Wickman Wickman, P-O.: Värdväxtbyte hos myrvisslaren, Pyrgus centaureae (lepidoptera: Hespe- riidae). [Hostplant shift in the northern grizzled skipper, Pyrgus centaureae (Lepidop- tera: Hesperiidae).] – Entomologisk Tidskrift 133 (3): 93-100. Uppsala, Sverige 2012. iSSn 0013-886x. This study for the first time describes the unusual life cycle of the northern grizzled skip- per, Pyrgus centaureae rambur, 1839, where the larvae shift host plant from dwarf birch, Betula nana, to cloudberry, Rubus chamaemorus. larvae were reared from eggs laid in June by a wild caught female. Eggs hatch after about 10 days in room temperature. The first instar larvae initially prefer leaves of dwarf birch but shift voluntarily to cloudberry leaves after their first moult. The larvae make a tent out of a couple of leaves on dwarf birch. On cloudberry, the tent is made by folding the edge of a leaf. The larvae spend their first winter as second instar larvae in a tent made from a cloudberry leaf. The first instar larva can use cloudberry for feeding, and the second instar larva can use dwarf birch. However, this seems only to occur when the host plant typical for the instar is not available. The cloudberry leaves are shed in the autumn and the tent with the larva spends the winter on the ground. The next summer the larvae complete their development at a size of about 20 mm and pupate above the ground in loosely knitted cocoons. The 13 mm long pupa hibernates. -

Ecological Site XA232X01Y201 Boreal Woodland Peat Frozen Terraces

Natural Resources Conservation Service Ecological site XA232X01Y201 Boreal Woodland Peat Frozen Terraces Last updated: 5/11/2020 Accessed: 10/01/2021 General information MLRA notes Major Land Resource Area (MLRA): 232X–Yukon Flats Lowlands The Yukon Flats Lowlands MLRA is an expansive basin characterized by numerous levels of flood plains and terraces that are separated by minimal breaks in elevation. This MLRA is in Interior Alaska and is adjacent to the middle reaches of the Yukon River. Numerous tributaries of the Yukon River are within the Yukon Flats Lowlands MLRA. The largest are Beaver Creek, Birch Creek, Black River, Chandalar River, Christian River, Dall River, Hadweenzic River, Hodzana River, Porcupine River, and Sheenjek River. The MLRA has two distinct regions— lowlands and marginal uplands. The lowlands have minimal local relief and are approximately 9,000 square miles in size (Williams 1962). Landforms associated with the lowlands are flood plains and stream terraces. The marginal uplands consist of rolling and dissected plains that are a transitional area between the lowlands and adjacent mountain systems. The marginal uplands are approximately 4,700 square miles in size (Williams 1962). This MLRA is bounded by the Yukon-Tanana Plateau to the south, Hodzana Highlands to the west, Porcupine Plateau to the east, and southern foothills of the Brooks Range to the north (Williams 1962). These surrounding hills and mountains partially isolate the Yukon Flats Lowlands MLRA from weather systems affecting other MLRAs of Interior Alaska. As a result, temperatures are generally warmer in summer and colder in winter than is characteristic in other areas at comparable latitude. -

Twenty of the Most Thermophilous Vascular Plant Species in Svalbard and Their Conservation State

Twenty of the most thermophilous vascular plant species in Svalbard and their conservation state Torstein Engelskjøn, Leidulf Lund & Inger Greve Alsos An aim for conservation in Norway is preserving the Svalbard archi- pelago as one of the least disturbed areas in the Arctic. Information on local distribution, population sizes and ecology is summarized for 20 thermophilous vascular plant species. The need for conservation of north- ern, marginal populations in Svalbard is reviewed, using World Conser- vation Union categories and criteria at a regional scale. Thirteen species reach their northernmost distribution in Svalbard, the remaining seven in the western Arctic. Nine species have 1 - 8 populations in Svalbard and are assigned to Red List categories endangered or critically endangered: Campanula rotundifolia, Euphrasia frigida, Juncus castaneus, Kobresia simpliciuscula, Rubus chamaemorus, Alchemilla glomerulans, Ranuncu- lus wilanderi, Salix lanata and Vaccinium uliginosum, the last four spe- cies needing immediate protective measures. Five species are classifi ed as vulnerable: Betula nana, Carex marina ssp. pseudolagopina, Luzula wahlenbergii, Ranunculus arcticus and Ranunculus pallasii. Six species are considered at lower risk: Calamagrostis stricta, Empetrum nigrum ssp. hermaphroditum, Hippuris vulgaris (only occurring on Bjørnøya), Juncus triglumis, Ranunculus lapponicus and Rhodiola rosea. The warmer Inner Arctic Fjord Zone of Spitsbergen supports most of the 20 target species and is of particular importance for conservation. Endan- gered or vulnerable species were found in a variety of edaphic conditions; thus, several kinds of habitats need protection. T. Engelskjøn, I. G. Alsos, Tromsø Museum, University of Tromsø, NO-9037 Tromsø, Norway, torstein@ tmu.uit.no; L. Lund, Phytotron, University of Tromsø, NO-9037 Tromsø, Norway. -

Draft Plant Propagation Protocol

Plant Propagation Protocol for [Rubus chamaemorus] ESRM 412 – Native Plant Production Protocol URL: https://courses.washington.edu/esrm412/protocols/[RUCH.pdf] TAXONOMY Plant Rosaceae Family Scientific Rubus Chamaemorus L. Name Common Cloudberry Name Species Scientif ic Name Scientific Rubus chamaemorus L. Name Varieties No information Sub- No information species Cultivar No information Common Synony m(s) Common Cloudberry, Bakeapple, Bakeapple Berry Name(s ) Species RUCH Code (as per USDA Plants databas e) GENERAL INFORMATION Geograph North America from Alaska south to British Columbia and east to Newfoundland ical and New York (Baskin & Baskin 2002). range Also see map above protocol (USDA Plants). Ecologica Found in sphagnum bogs and peaty soil from the lowlands to montane zones. l Circumboreal species. Grows in organic but relatively dry soil with sandy subsoils distribut (Baskin & Baskin 2002). ion Found in cool boggy environments, on hills and mountains. (http://www.pfaf.org/ 2012). Grows well in sandy, loamy, and clay soils and prefers well-drained soil. It can also grow in very acid soils. It cannot grow in the shade. It prefers moist or wet soil. (http://www.pfaf.org/ 2012). The most favorable growing conditions are obtained on peat bogs between 0.5 and 1 meter in depth, with pH-values between 3.5 and 4.5, and with the ground water 40 to 50 cm below the surface (Rapp et al. 1993). Can tolerate minimum temperature of -38 degrees F. Grows in soil of pH between 4 and 5.2 (USDA Plants). Climate Mostly low elevation bogs (Pojar & Mackinnon 1994), but also may grow in and montane areas (Baskin & Baskin 2002). -

Partnering with Alaska Native Communities to Link Science and Traditional Ecological Knowledge of Wild Berry Resources

Partnering with Alaska Native Communities to Link Science and Traditional Ecological Knowledge of Wild Berry Resources Joshua Kellogg, Courtney Flint, Gary Ferguson, Ilya Raskin, Mary Ann Lila June 8, 2010 2010 National Tribal Science Forum Participatory Research Framework Key Informant Site Visits Interviews Secondary Data Subsistence Risk Perceptions Health Resource Use Interviews Student-led Community Traditional Berries Wellness Knowledge Laboratory Laboratory Validation Environmental Youth – Elder Bioactivity of Ongoing Change Interface Wild Berries Communication Household Surveys Screens to Nature Screens-to-Nature (STN) System • Portfolio of 20 qualitative field bioassays • Medium-throughput techniques • Primary indicators of bioactivity • Participatory research tool STN Characteristics • Field-deployable kits •Colorimetric/visual indicators • Accessible to all science backgrounds • Accurate, reproducible assay techniques • Engaging, inclusive methodology for working with communities Alaskan Berries • 5 species analyzed, based upon community recommendations • Vaccinium uliginosum (“lowbush blueberry”) • Vaccinium ovalifolium (“highbush blueberry”) Alaskan Berries • 5 species analyzed, based upon community recommendations • Emptrum nigrum (“blackberry”, “mossberry”, “crowberry”) Alaskan Berries • 5 species analyzed, based upon community recommendations • Rubus spectabilis (“salmonberry”) • Rubus chamaemorus (“salmonberry”, “cloudberry”) Assay Selection for Alaska • Related to Alaska Native health concerns • Protease/Protease Inhibition -

Chemical Composition of Ripe Fruits of Rubus Chamaemorus L. Grown In

Research Article Received: 11 March 2011 Revised: 21 July 2011 Accepted: 14 September 2011 Published online in Wiley Online Library: 14 November 2011 (wileyonlinelibrary.com) DOI 10.1002/jsfa.4705 Chemical composition of ripe fruits of Rubus chamaemorus L. grown in different habitats Mari Jaakkola,a∗ Ville Korpelainen,b Kalle Hoppulab and Vesa Virtanena Abstract BACKGROUND: Cloudberry (Rubus chamaemorus L.) is one of the most valuable berry-producing plants because of its nutritional properties. The chemical composition and crop yield of ripe fruits of cloudberry grown wild in 10 habitats in northern Finland was analysed over two consecutive summers. For comparison, two clones of cultivated cloudberries were studied as well. RESULTS: The concentrations of citric and malic acids, α-tocopherol, anthocyanins and β-carotene had notable variations between habitats. In particularly, cloudberries grown on open habitats had higher content of citric acid and less α-tocopherol compared to those grown on shaded sites. In a colder and rainy summer the content of anthocyanins and the unsaturation level of fatty acids were significantly higher than in a warmer and drier summer. Crop yields were higher in the warmer summer, except in open sites where yields were quite equal. CONCLUSION: Cloudberries grown in open habitats showed notable differences in chemical composition when compared to those grown on shaded sites. Results suggest that the amount of sunlight and temperature levels could be the main factors affecting crop yield and chemical composition of cloudberry. In addition, the amount of rainfall may have an effect on anthocyanin concentrations. c 2011 Society of Chemical Industry Keywords: Rubus chamaemorus L.; cloudberry; chemical composition; crop yield; habitats INTRODUCTION been developed in Finland, Norway and North America, but Rubus chamaemorus (Rosaceae) is one of the most valuable there are still problems with profitability due to the high berry-producing plants because of its nutritional properties costs.11,12 and distinctive flavour. -

Minnesota's List of Endangered, Threatened and Special Concern

MINNESOTA'S LIST OF ENDANGERED, THREATENED, AND SPECIAL CONCERN SPECIES PURPOSE, SCOPE, AND RELATIONSHIP TO FEDERAL LAWS Minnesota’s Endangered Species Statute (Minnesota Statutes, Section 84.0895) requires the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources (DNR) to adopt rules designating species meeting the statutory definitions of endangered, threatened, or species of special concern. The resulting List of Endangered, Threatened, and Special Concern Species is codified as Minnesota Rules, Chapter 6134. The Endangered Species Statute also authorizes the DNR to adopt rules that regulate treatment of species designated as endangered and threatened. These regulations are codified as Minnesota Rules, Parts 6212.1800 to 6212.2300. Minnesota’s Endangered Species Statute and the associated Rules impose a variety of restrictions, a permit program, and several exemptions pertaining to species designated as endangered or threatened. A person may not take, import, transport, or sell any portion of an endangered or threatened species. However, these acts may be allowed by permit issued by the DNR; plants on certain agricultural lands and plants destroyed in consequence of certain agricultural practices are exempt; and the accidental, unknowing destruction of designated plants is exempt. Species of special concern are not protected by Minnesota’s Endangered Species Statute or the associated Rules. Persons are advised to read the full text of the Statute and Rules in order to understand all regulations pertaining to species that are designated as endangered, threatened, or species of special concern. Note that the federal Endangered Species Act of 1973, as amended (16 USC 1531 - 1544) requires the U.S. Department of the Interior to identify species as endangered or threatened according to a separate set of definitions, and imposes a separate set of restrictions pertaining to those species.