Developing Sustainable International Library Exchange Programs: the CUNY-Shanghai Library Faculty Exchange Model Sheau-Yueh]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

RADICAL ARCHIVES Presented by the Asian/Pacific/American Institute at NYU Curated by Mariam Ghani and Chitra Ganesh

a/p/a RADICAL ARCHIVES presented by the Asian/Pacific/American Institute at NYU curated by Mariam Ghani and Chitra Ganesh Friday, April 11 – Saturday, April 12, 2014 radicalarchives.net Co-sponsored by Asia Art Archive, Hemispheric Institute, NYU History Department, NYU Moving Image Archive Program, and NYU Archives and Public History Program. Access the Internet with NYU WiFi SSID nyuguest login guest2 password erspasta RADICAL ARCHIVES is a two-day conference organized around the notion of archiving as a radical practice, including: archives of radical politics and practices; archives that are radical in form or function; moments or contexts in which archiving in itself becomes a radical act; and considerations of how archives can be active in the present, as well as documents of the past and scripts for the future. The conference is organized around four threads of radical archival practice: Archive and Affect, or the embodied archive; Archiving Around Absence, or reading for the shadows; Archives and Ethics, or stealing from and for archives; and Archive as Constellation, or archive as method, medium, and interface. Advisory Committee Diana Taylor John Kuo Wei Tchen Peter Wosh Performances curated Helaine Gawlica (Hemispheric Institute) with assistance from Marlène Ramírez-Cancio (Hemispheric Institute) RADICAL ARCHIVES SITE MAP Friday, April 11 – Saturday, April 12 KEY 1 NYU Cantor Film Center 36 E. 8th St Restaurants Coffee & Tea 2 Asian/Pacific/American Institute at NYU 8 Washington Mews Cafetasia Cafe Nadery Oren’s 3 NYU Bobst -

The Newsletter of the Lloyd Sealy Library Fall 2013

lloyd sealy library Classified Information The Newsletter of the Lloyd Sealy Library Fall 2013 From the Desk of the Chief Librarian he Lloyd Sealy Library is appropriately named after the an adjunct professor of corrections at John Jay. He died on Tfirst African-American to reach the rank of Assistant June 10, 2002. Chief Inspector in the New York City Police Department. Some years ago, John Jay President Jeremy Travis, who Mr. Sealy’s promotion came in 1966, some 55 years after from 1984–1986 served as Special Counsel to Commissioner Samuel J. Battle became New York’s first African-American Benjamin Ward, and this librarian entered into negations police officer in 1911 under the charter that consolidated the with the Ward family for the late commissioner’s private boroughs in 1898. Mr. Sealy was also a member of our fac- papers. We are pleased to say that we were successful and ulty after his retirement. This brief history goes by way of that the extant papers are safely housed in the Lloyd Sealy saying that on January 5, 1984, Mayor Edward Koch swore Library’s Special Collections Division. The holdings include in Benjamin Ward as the city’s first African-American Police numerous important documents, letters, and his unpub- Commissioner. Mr. Ward had a long career in public service. lished autobiography Top Cop. After he became the first black officer to patrol Brooklyn’s Researchers are encouraged to look at the finding aid and 80th precinct, he quickly rose to the rank of Lieutenant, use this most valuable collection. -

Download Newsletter (PDF)

lloyd sealy library Classified Information The Newsletter of the Lloyd Sealy Library Fall 2017 Inside: Open & alternative educational resources New feature films & documentaries BrowZine, a new app for browsing journals An interview with Bonnie Nelson The 1923 personal diary of Lawrence Schofield, a detective hired by a department store. See inside cover for comments from Chief Librarian Larry Sullivan. john jay college of criminal justice 1 classified information Table of contents Fall 2017 Faculty notes Library News Videos Larry Sullivan co-authored (with Kim- Bonnie Nelson retires 4 New documentaries 14 berly Collica of Pace University) the peer- reviewed article, “Why Retribution Matters: Notes of appreciation 8 New feature films 15 Progression Not Regression,” in Theory in Students escape the Library 7 Action vol. 10, no. 2, April 2017. His section Database highlights: Collections Development on “Prison Writing” was accepted for publi- Economic research 9 History of swimming 16 cation in The Oxford Bibliography of Ameri- Current events 17 Virtual browsing 16 can Literature. He is Editor-in-Chief of the The new RefWorks 10 A special dedication 16 recently published annual Criminal Justice and Law Enforcement: Global Perspectives Workshops for grad students 10 Transnational blackness 17 (John Jay Press, 2017). He was Series Con- OER/AER at CUNY 11 sultant and wrote the forward to the nine- Introducing BrowZine 12 Special Collections volume The Prison System (Mason Crest, This is an editorial! 13 Courtroom artists 18 2017). He wrote the review for The Morgan Library and Museum’s Sept. 9, 2016 – Jan. 2, 2017 exhibition, “Charlotte Bronte: An Inde- pendent Will,” which appeared in newslet- From the desk of the Chief Librarian ter of the Society for the History of Reading, The daily life and travails of a Boston department store detective Authorship, and Publishing (SHARP) in Larry Sullivan Spring 2017. -

RBMS Newsletter

Y.s&ted &, tk ~ 0oob aad ~ RBMS Jecao-a, [!/tlw ~ e/C?o/49e, mu1 ~ ~/'WP, {l/ 0~[!/tk Newsletter ./Cou:ricmv ~ ~Iv FALL 1995 NUMBER23 of Rare Books, Manuscripts and Other Special Collections. From the Chair This review will be led by the Security Committee. Highlights reetings to all RBMS members. After last summer's of the work of other committees are included elsewhere in this Preconference in Bloomington, I feel as ifl know issue. many more of you than I did before. Here on the Communication is perhaps the most important element in Indiana University campus we were welcomed successful change. Please make use of the directory informa mback to the campus this Fall with a letter from Indiana Univer tion in this newsletter to be in touch with members of the sity President Myles Brand declaring that "avoidance of change Executive Committee. Participation of all RBMS members is not an option." His remarks were directed to his initiative to helps insure that we will fulfill our mission to represent and make Indiana University America's new public university. In promote the interests of librarians, curators, and other special later presentations he has admonished us with "change or be ists concerned with the care, custody, and use of rare books, changed" and delivered a strategic directions document which manuscripts, and archives. has funding and resource allocation implications. Many of -Elizabeth Johnson these same themes are being sent out to ACRL sections from the division headquarters. We as a section must respond and in fact have an opportunity now to direct the nature of the changes being made. -

~ ~ T Criminal Justice T Information Exchange

If you have issues viewing or accessing this file contact us at NCJRS.gov. u.s. Department of Justice National Institute of Justice Naiional Criminal Justice Referenl~e Service Box 6000, Ro('kl'ille, MD 20850 ~ ~t Criminal Justice t Information Exchange 12TH EDITION 1993 13 u.s. Department of Justice /L)q'7 National Institute of Justice National Criminal Justice Reference Service Box 6{){)O. RO('k\'ille. MD 20H50 ~t Criminal Justice ~ ..t Information Exchange 12TH EDITION 1993 149713 U.S. Department of Justice National Institute of Justice This document has been reproduced exactly as received from the person or organization originating it. Points of view or opinions stated in this document are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position or policies of the National Institute of Justice. Permission to reproduce this 'I ; iii W- material has been granted by pubJic Domain/NIJ/NCJRS u.s. Department of Justice to the National Criminal Justice Reference Service (NCJRS). Further reproduction outside of the NCJRS system requires permission of the~ owner. Table of Contents Introduction i Index By Library Name ii-viii CJIE Entries ,.\ 1-104 ~ GPO Regional Depository Libraries 105 Glossary 109 Introduction The National Institute of Justice/NCJRS is proud to sponsor the Criminal Justice Information Exchange (CJIE), an informal, cooperative association of libraries serving the criminal justice community. The Exchange aims to foster better communication and cooperation among member libraries and to enhance user services. Member libraries can improve services in the criminal justice area through information exchange and interlibrary loan. In addition, group members furnish criminal justice patrons with information about CJIE collections, policies, and services. -

Classified Information the Newsletter of the Lloyd Sealy Library Fall 2015

lloyd sealy library Classified Information The Newsletter of the Lloyd Sealy Library Fall 2015 From the Desk of the Chief Librarian Law codes, both penal and civil, rarely make for exciting reading. Just think of spending a pleasant evening brows- ing through the over 13,000-page Internal Revenue Service regulations (Title 26 of the U.S. Code of Federal Regulations). In France, however, which perhaps is more bureaucratic than the United States, the artist Joseph Hé- mard (1880-1961), a well-known French book illustrator, decided to satirize a number of French statutes through his amusing, mildly erotic drawings. In his work, Hémard used the pochoir (stencil) technique, which is a hand-col- ored illustration process that began in the 15th century for playing cards and the occasional woodcut. Having fallen out of use for centuries, the French revived the technique in the late 19th century. The handwork that produces the brilliantly colored illustrations is very costly and rarely used in the book printing process. The Sealy Library was fortunate to obtain two rare edi- tions of these works: Code Pénal (late 1920s) and Code Civil: Livre Premier, Des Personnes.... (1925). The latter pokes fun at a number of laws including divorce, pater- nity, adoption, and paternal authority (e.g., Article 371), which states, “The infant at any age must honor and re- spect his mother and father.” Article 378 mandates that the father alone exercises authority over the child during the marriage and until the child reaches his or her major- ity (18 years). The illustrations comically make such regu- lations clear and accessible to the reader. -

FY 2021 Executive Budget Capital Project Detail

Capital Project Detail Data Fiscal Year 2021 Capital Commitment Plan Manhattan The City of New York Bill de Blasio, Mayor Mayor’s Office of Management and Budget Melanie Hartzog, Director April 2020 April 2020 Index for MANHATTAN Page: 1 Capital Construction Project Detail Data Community Project Id Boards Description Page Aging, Department for the (AG) Department For The Aging (125) AGCBCOV 311 CARTER BURDEN/LEONARD COVELLO 193 AGCBURDEN 311 LEONARD COVELLO Kitchen Renovation 194 HAM14CRSR 311 CARVER HOUSES SENIOR CENTER COMPUTER LAB 195 Housing Preservation And Devel (806) HAM15JFSR 311 JEFFERSON SENIOR CENTER UPGRADE 375 Dept Of Design & Construction (850) AGNYCHANG 303 NYCHANGE PROJECT WITH DFTA 950 Dept Of Citywide Admin Servs (856) AG1RAND 309 DFTA -108- ST RANDOLPH SC 1137 AGHVACRM 301 2 Lafayette 9th floor DFTA IT room HVAC upgrade 1138 Business Services, Department of Economic Development, Office of (ED) Dept Of Small Business Services (801) 125THPDIM 300 125th St & Park Ave - Pedestrian Improvements 221 1680LEXSP 300 1680 Lexington Sound Proofing 222 34STHELI 301 306 308 E. 34th Street Heliport Rehabilitation 223 8890PHA3 300 Piers 88 & 90 Cluster Encapsulation Project Phase 3 226 8THSTPAVE 300 302 8th St Bluestone Pavement Replacement 227 8THSTREET 302 FA - Village Alliance - Reconstruction of St. & Sidewalks 228 AHGREEN 300 Andrew Haswell Green Park - Phase 2B 229 CWFSFERY2 300 New York City Ferry - Infrastructure 233 DMECODOCK 300 Dyckman Pier -- Ferry Access to Eco-Dock 234 EASTPLAZA 300 311 East River Plaza 236 EDCLUMP 300 -

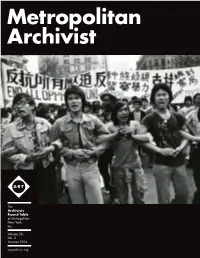

The Archivists Round Table of Metropolitan New York, Inc. Volume 20, No. 2 Summer 2014

Metropolitan Archivist The Archivists Round Table of Metropolitan New York, Inc. Volume 20, No. 2 Summer 2014 nycarchivists.org Welcome! The following individuals have joined the Archivists Round Table We extend a special thank you to the following of Metropolitan New York, Inc. (A.R.T.) from January 2014 to June 2014 members for their support as A.R.T. Sustaining Members: Gaetano F. Bello, Corrinne Collett, New Members Anthony Cucchiara, Constance de Ropp, Barbara John Brokaw Haws, Chris Lacinak, Sharon Lehner, Liz Kent Cynthia Brenwall León, Alice Merchant, Sanford Santacroce Maureen Callahan The Michael Carter Thank you to our Sponsorship Members: Archivists Celestina Cuadrado Ann Butler, Frank Caputo, Linda Edgerly, Chris Round Table of Metropolitan Jacqueline DeQuinzio Genao, Celia Hartmann, David Kay, Stephen New York, Elizabeth Fox-Corbett Perkins, Marilyn H. Pettit, Alix Ross, Craig Savino Inc. Tess Hartman-Cullen Carmen Lopez The mission of Metropolitan Archivist is to Sam Markham serve members of the Archivists Round Table of Volume 20, Brian Meacham Metropolitan New York, Inc. (A.R.T.) by: No. 2 Chloe Pfendler - Informing them of A.R.T. activities through Summer 2014 David Rose reports of monthly meetings and committee Angela Salisbury activities nycarchivists.org Natalia Sucre - Relating important announcements about Marissa Vassari individual members and member repositories - Reporting important news related to the New York Board of Directors New Student Members metropolitan area archival profession Pamela Cruz Carlos Acevado - Providing a forum to discuss archival issues President Elizabeth Berg Ryan Anthony Thomas Cleary Metropolitan Archivist (ISSN 1546-3125) is Donaldson Vice President Rina Eisenberg issued semi-annually to the members of A.R.T. -

Metro Delivers

METRO DELIVERS Member Directory and Delivery Roster | February 2013 For the most up-to-date information, visit METRO’s online member directory at www.metro.org To update your institution’s information, please contact Mark Parson at 212.228.2320 x121 or [email protected] METRO DELIVERS QUICK REFERENCE LABELING Each package must have a unique transaction number as part of the address. This number will be used to assist in tracking all shipments. Each transaction number has two parts: 1. Delivery number of the shipper and the receiver separated by a “>” 2. Date and package number o The date should be all numbers with no separation between month and day and is followed by a “-“ and the package number. o For the date, use the date of the next scheduled pick-up, not the day the entry is made. For example: If METRO (154) is sending a package to Hunter College (104) on November 14th and it is the first shipment, the label should read: Hunter College, CUNY Wexler Library 695 Park Ave. 3rd fl New York, NY 10065 154>104 1114-1 SHIPPING LOG A shipping log must be prepared for all shipments (example below). The log functions as a receipt and should be signed by the driver. All logs should be retained. The shipping log should be put out for each pick up day. A copy of the shipping log may be printed out at http://www.metro.org/attachments/files/85/res_shiplog.pdf METRO Delivers Shipping Log Member Name: Pick-up Date: Transaction # Destination Contents Example: Your number → Destination number – Date → - 1 → - 2 → - 3 Delivery Driver Signature: _________________________ Date: ________ METRO Member Directory and Delivery Roster WINTER 2013 A.T.I.M.E TITLE REFERRAL CARD: Yes A.T.I.M.E. -

Download Newsletter (PDF)

lloyd sealy library Classified Information The Newsletter of the Lloyd Sealy Library Fall 2018 Inside: New streaming videos from AVON Tracing transnational organized crime Early twentieth century criminals & police john jay college of criminal justice 1 classified information Table of contents Fall 2018 Faculty notes Library News Collections Kathleen Collins published “Co- NYPL Shared Collection 4 New acquisitions 11 median Hosts and the Demotic New study spaces unveiled 6 World Atlas of Illicit Flows 12 Turn” in Llinares, Fox, and Berry, The ends pre-exist in the means 7 Docuseek2 Complete Collection 13 eds. Podcasting: New Aural Cultures Academic Videos Online 14 and Digital Media (Palgrave Mac- Databases & Media millan, 2018), available to read on Slavery in America & the World 8 Special Collections CUNY Academic Works. Finding cases using Nexis Uni 9 Early twentieth century criminals 16 Robin Davis gave a presentation, SimplyE: NYPL ebooks 10 “Keep it secret, keep it safe! Preserv- ing anonymity by subverting sty- In Brief lometry” in October at PyGotham, Haaren Hall through the years 5 The online edition of this newsletter is Library faculty favorites 19 available at jjay.cc/news an annual conference for Python programmers in New York City. With Mark Eaton, a librarian at KBCC, she led “Python for Beginners: A Gentle and Fun Introduction,” a LITA Pre- Library news in brief Conference Institute at the ALA An- nual Conference, which took place in New Orleans in June 2018. Maria Kiriakova published “Com- batting Corruption in the USA: State, Dynamics, and Tendencies,” co-written with Y. Truntsevsky, in Public International and Private In- ternational Law: Science-Practice and Information Journal, vol. -

Crime in the Library! the Special Collections of Lloyd Sealy Library, John Jay College of Criminal Justice/CUNY: a Repository Profile

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Publications and Research John Jay College of Criminal Justice 2008 Crime in the Library! The Special Collections of Lloyd Sealy Library, John Jay College of Criminal Justice/CUNY: A Repository Profile. Ellen H. Belcher CUNY John Jay College How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/jj_pubs/121 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] Page 25 REPOSITORY PROFILES Crime in the Library: The Special Collections of the Lloyd Sealy Library, John Jay College of Cri1ninal Justice/CUNY The Ruth St. Denis Collection at the Adelphi University Archives and Special Collections Crime in the Library: The Special Collections of the Lloyd Sealy Library, John Jay College of Criminal Justice By Ellen H. Belcher Introduction Started as a small collection of books to support the New York Police Department (NYPD) Police Academy, the library of John Jay College of Criminal Justice has had a rich history and built important collections in just over four decades. The library has always had a mission to collect comprehensively in criminal justice and its collections have paralleled the college in the scholarly development of the field. The library holds the papers and publications of prisoners and prison wardens; criminals and policemen; Photograph of Sergeant Edu:ard 0. Shibles, NYPD. From The Shibles scholars of criminal behavior and supporters of Family Papers, Lloyd Sealy Library . -

Jeffrey A. Kroessler Lloyd Sealy Library John Jay College of Criminal Justice 899 Tenth Avenue New York, NY 10019 212-237-8236 / [email protected]

Jeffrey A. Kroessler Lloyd Sealy Library John Jay College of Criminal Justice 899 Tenth Avenue New York, NY 10019 212-237-8236 / [email protected] CURRENT POSITION Associate Professor, Lloyd Sealy Library, John Jay College of Criminal Justice, CUNY Head of circulation; reference and library instruction; Oral History of Criminal Justice: conducting interviews and preparing transcripts for the collection. EDUCATION Queens College, CUNY M.L.S. 2004 CUNY Graduate School Ph.D., American History 1991 Dissertation: “Building Queens: the urbanization of New York‟s largest borough;” Advisor: Richard C. Wade New York University M.A., History 1978 Hobart College B.A., History 1973 PUBLICATIONS Books The Greater New York Sports Chronology. Columbia University Press, 2010. College of Staten Island Oral History Project, 12 volumes, 2005: Senator John J. Marchi; The Staff of Senator John J. Marchi; Staten Islanders; Staten Island Politics; New York City Politics; New York State Politics; Elizabeth Connelly; Robert Straniere; Conversations on Politics; College of Staten Island; 9-11-2001; Master Index. New York, Year by Year: A Chronology of the Great Metropolis. New York University Press, 2002 (named “Best of Reference” by the New York Public Library, 2002). Lighting the Way: A Centennial History of the Queens Borough Public Library, 1896- 1996. QBPL, 1996. Historic Preservation in Queens. Queensborough Preservation League, 1990. A Guide to Historical Map Resources for Greater New York. Chicago: Speculum Orbis Press, 1988 (sponsored by the Social Science Research Council). Books in Progress Bombing for Justice: Urban Terrorism in New York City, 1964-1993. Building Queens: Development, Density, and Diversity (Temple University Press).