Thesis (254.7Kb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Adventures of Tom Sawyer by Mark Twain

THE ADVENTURES OF TOM SAWYER BY MARK TWAIN (Samuel Langhorne Clemens) Complete Ebd E-BooksDirectory.com PREFACE Most of the adventures recorded in this book really occurred; one or two were experiences of my own, the rest those of boys who were schoolmates of mine. Huck Finn is drawn from life; Tom Sawyer also, but not from an individual—he is a combination of the characteristics of three boys whom I knew, and therefore belongs to the composite order of architecture. The odd superstitions touched upon were all prevalent among children and slaves in the West at the period of this story—that is to say, thirty or forty years ago. Although my book is intended mainly for the entertainment of boys and girls, I hope it will not be shunned by men and women on that account, for part of my plan has been to try to pleasantly remind adults of what they once were themselves, and of how they felt and thought and talked, and what queer enterprises they sometimes engaged in. THE AUTHOR. HARTFORD, 1876. THE ADVENTURES OF TOM SAWYER BY MARK TWAIN (Samuel Langhorne Clemens) Part 1. Ebd E-BooksDirectory.com CHAPTER I "TOM!" No answer. "TOM!" No answer. "What's gone with that boy, I wonder? You TOM!" No answer. The old lady pulled her spectacles down and looked over them about the room; then she put them up and looked out under them. She seldom or never looked THROUGH them for so small a thing as a boy; they were her state pair, the pride of her heart, and were built for "style," not service—she could have seen through a pair of stove-lids just as well. -

The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, Complete By

The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, Complete By Mark Twain (Samuel Clemens) 1 P R E F A C E MOST of the adventures recorded in this book really occurred; one or two were experiences of my own, the rest those of boys who were schoolmates of mine. Huck Finn is drawn from life; Tom Sawyer also, but not from an individual--he is a combination of the characteristics of three boys whom I knew, and therefore belongs to the composite order of architecture. The odd superstitions touched upon were all prevalent among children and slaves in the West at the period of this story--that is to say, thirty or forty years ago. Although my book is intended mainly for the entertainment of boys and girls, I hope it will not be shunned by men and women on that account, for part of my plan has been to try to pleasantly remind adults of what they once were themselves, and of how they felt and thought and talked, and what queer enterprises they sometimes engaged in. THE AUTHOR. HARTFORD, 1876. 2 T O M S A W Y E R CHAPTER I "TOM!" No answer. "TOM!" No answer. "What's gone with that boy, I wonder? You TOM!" No answer. The old lady pulled her spectacles down and looked over them about the room; then she put them up and looked out under them. She seldom or never looked THROUGH them for so small a thing as a boy; they were her state pair, the pride of her heart, and were built for "style," not service--she could have seen through a pair of stove-lids just as well. -

13-19-00125-CR Liscano V State of Texas

NUMBER 13-19-00125-CR COURT OF APPEALS THIRTEENTH DISTRICT OF TEXAS CORPUS CHRISTI – EDINBURG SAMUEL TREVINO LISCANO, Appellant, v. THE STATE OF TEXAS, Appellee. On appeal from the 398th District Court of Hidalgo County, Texas. MEMORANDUM OPINION Before Justices Hinojosa, Perkes, and Tijerina Memorandum Opinion by Justice Tijerina Appellant Samuel Trevino Liscano appeals his conviction of aggravated sexual assault of a child under six. See TEX. PENAL CODE ANN. § 22.021(a)(1)(B)(i), (f)(1) (enhancing minimum punishment to twenty-five years’ confinement if the child is under the age of six when the offense is committed). Liscano was sentenced to life imprisonment. See id. § 12.42(c)(2) (enhancing punishment range to life imprisonment if the defendant is convicted of an offense pursuant, to among others, § 22.021 and has previously been convicted under § 20A.02(a)(7) or (8), § 21.02, 21.11, § 22.011, § 22.021, or § 25.02). By three issues, Liscano contends that the evidence is insufficient and the “presence of third parties in the jury room during the deliberations violated” his right to a fair and impartial jury.1 We affirm as modified. I. SUFFICIENCY OF THE EVIDENCE A. Standard or Review and Applicable Law In determining the sufficiency of the evidence, we consider all the evidence in the light most favorable to the verdict and determine whether a rational fact finder could have found the essential elements of the crime beyond a reasonable doubt based on the evidence and reasonable inferences from that evidence. Whatley v. State, 445 S.W.3d 159, 166 (Tex. -

To the Angelbeast

To the Angelbeast To the Angelbeast, collected, Natalie Diaz, Joanna Penn Cooper, Portable Press, Lori Desrosiers, Gregory Lawless, Waldman Lori Desrosiers, heavy metal music, Monica Youn, John Gallaher, Driest Place on Earth, Emilia Phillips Essay, dead writers, Cecelia Holmes, a trick of the light, Eduardo C. Corral, Arthur Russell Eduardo C. Corral, Space Chimp, Emilia Phillips, Sophie Klahr Frantic, Jay Besemer, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, University of Virginia Abort, Hail Mary, Abigail Thomas, Rachel Mennies, Jennie Malboeuf, Susan Slaviero, Journal Rachel Mennies, Reginald Shepherd, Adrian Matejka, Magnolia trees, Marni Ludwig, Simpleton Sarah, David Kirby, Shanna Compton, Marcus Wicker, Alice Anderson, Emma Winsor Wood, Queen Elizabeth The transition handbook, Books are available in hardcopy or ebooks, Human sexuality: Diversity in contemporary America, Nurses Knowledge and Practice Regarding Gastrointestinal Endoscopy and Suggested Nursing Guidelines, John Steinbeck: The Good Companion, The Book of Concord, Dust tracks on a road, Saccharomyces boulardii effects on gastrointestinal diseases, Losing ground, Financing education in developing Asia: themes, tensions, and policies To the Angelbeast For Arthur Russell All that glitters isn‘t music. Once, hidden in tall grass, I tossed fistfuls of dirt into the air: doe after doe of leaping. You said it was nothing but a trick of the light. Gold curves. Gold scarves. Am I not your animal? You‘d wait in the orchard for hours to watch a deer break from the shadows. You said it was like lifting a cello out of its black case. Eduardo C. Corral 1 1 Eduardo C. Corral, “To the Angelbeast,” in Poetry, collected in Slow Lightning, Yale Age of Beauty This is not an age of beauty, I say to the Rite-Aid as I pass a knee-high plastic witch whose speaker-box laugh is tripped by my calf breaking the invisible line cast by her motion sensor. -

Adventures of Tom Sawyer

The Adventures of Tom Sawyer Mark Twain THE EMC MASTERPIECE SERIES Access Editions SERIES EDITOR Robert D. Shepherd EMC/Paradigm Publishing St. Paul, Minnesota Staff Credits: For EMC/Paradigm Publishing, St. Paul, Minnesota Laurie Skiba Eileen Slater Editor Editorial Consultant Shannon O’Donnell Taylor Jennifer J. Anderson Associate Editor Assistant Editor For Penobscot School Publishing, Inc., Da nvers, Massachusetts Editorial Design and Production Robert D. Shepherd Cha rles Q. Bent President, Executive Editor Production Manager Christina E. Kolb Sara Day Managing Editor Art Director Kim Leahy Beaudet Diane Castro Editor Compositor Sara Hyry Janet Stebbings Editor Compositor Laurie A. Faria Associate Editor Sharon Salinger Copyeditor Marilyn Murphy Shepherd Editorial Advisor ISBN 0-8219-1637-8 Copyright © 1998 by EMC Corporation All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be adapted, reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, elec- tronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without permis- sion from the publishers. Published by EMC/Paradigm Publishing 875 Montreal Way St. Paul, Minnesota 55102 Printed in the United States of America. 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 xxx 06 05 04 03 02 01 00 Table of Contents The Life and Works of Mark Twain. v Time Line of Twain’s Life . vii The Historical Context of The Adventures of Tom Sawyer. ix Characters in The Adventures of Tom Sawyer . xiii Illustrations. xvi Echoes . xviii Preface . 1 Chapter 1 . 3 Chapter 2 . 11 Chapter 3 . 17 Chapter 4 . 23 Chapter 5 . 32 Chapter 6 . 39 Chapter 7 . 49 Chapter 8 . -

The Philosophy of Dostoevsky's Characters

Trinity College Trinity College Digital Repository Senior Theses and Projects Student Scholarship Spring 5-2-2011 The Mystery of Suffering: The Philosophy of Dostoevsky's Characters Elizabeth J. Ewald Trinity College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.trincoll.edu/theses Part of the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Ewald, Elizabeth J., "The Mystery of Suffering: The Philosophy of Dostoevsky's Characters". Senior Theses, Trinity College, Hartford, CT 2011. Trinity College Digital Repository, https://digitalrepository.trincoll.edu/theses/18 The Mystery of Suffering: the Philosophy of Dostoevsky’s Characters Elizabeth Ewald Religion Department Senior Thesis Trinity College, May 2011 1 Acknowledgements: I firstly like to sincerely thank Dr. Frank Kirkpatrick for the time spent reading drafts, posing critical questions and comments, and discussing ideas. I would also like to thank Professor Homayra Ziad for her role as a second thesis reader, and Professor Carol Any for her constructive criticism. 2 Table of Contents: Introduction: 4 Dostoevsky and the Russian Orthodox Sufferer: 7 Dostoevsky’s Denunciation of Socialist Conceptualizations of Suffering: 30 Psychological Suffering for a Religious Idea: 40 Conclusion: 46 Bibliography: 48 3 Introduction A keen reader will notice certain repetitions in Dostoevsky’s novels – not of themes or motifs, though those do exist. There is a much more subtle repetition in his works, of an unsettlingly dark nature. Dostoevsky frequently employed the same stories (and historical accounts, cases from newspapers included) of horrific suffering in different works. The mention of a man brutally murdering two women in The Idiot is the central theme in Crime and Punishment , and the chapter about the inhumane torture of an old horse in Crime and Punishment is commented on in Demons . -

SPRING 1986 ENERGEIA: the Activity in Which Anything Is Fully Itself

SPRING 1986 ENERGEIA: The activity in which anything is fully itself. ~ ... vou ev&pyew. ~co~ ... (Aristotle's Metaphysics, 1072b) Cover: The Emerging Odyssey by Jennifer A. Lapham Ink and Watercolor Staff: Barbara Gesiakowski Chris Howell Steve Jackson A.J. Krivak Printed by the Bernadette Rudolph St. John's College Press Co-Editors: St. John's College Gabrielle Fink Annapolis, Maryland Joseph MacFarland Faculty Advisor: Jonathan Tuck Energeia is a non-profit, student magazine which is published three times a year and distributed among the students, faculty, alumni and staff of St. John's College, Annapolis and Santa Fe. The Fall issue contains a sampling of the student work from the previ ous school year which the prize committees of both campuses have selected for public recognition. For the Winter and Spring issues, the Energeia staff welcomes submissions from all members of the commun~ty-essays, poems, stories, original math proofs, lab projects, drawings, and the like. Note: A brief description of the author accompanies all work not by current St. John's students. Please include some such statement along with your submission. Thank you. CONTENTS PHOTOGRAPH Christopher K. Watson 1 THE CHARACTER OF A METER David Amirthanayagam 2 POEM James Brown 8 THE GORGON AND THE BRIDE OF LEBANON Catherine Irvine 10 SOCRATES Elizabeth De Mare 22 THE JACOBSEN CUT: A GEOMETRICAL PROPOSITION Henry Higuera 27 PHOTOGRAPH Christopher K. Watson 33 PURGATION OF THE HUMAN SPIRIT William O'Grady 34 A WAY TO THINK ABOUT DARK TIMES William O'Grady 40 TWO POEMS: #3 AND #8 Stuart Sobczynski 45 FINAL CAUSE AND THE PROBLEM OF EXISTENCE Jim Guszca 46 ANTIGONE Hugh Brantner 49 THREE FACES (WATERCOLOR) Yolanda Rivera 55 SONNET FOR A SLAVIC MINER A.J. -

Open Thesis.Pdf

THE PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIVERSITY SCHREYER HONORS COLLEGE DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH ―PUNISHED IN THE SHAPE HE SINNED‖: SIN AS SELF-PUNISHING IN DANTE AND MILTON LAURA B.ALBANESE Summer 2010 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for baccalaureate degrees in English and Italian Language and Literature with honors in English Reviewed and approved* by the following: Laura L. Knoppers Professor of English Thesis Supervisor Sherry L. Roush Associate Professor of Italian Second Reader Janet W. Lyon Associate Professor of English, Women‘s Studies Honors Adviser * Signatures are on file in the Schreyer Honors College. ABSTRACT This paper explores the question of punishment as seen in Milton‘s Paradise Lost. Milton‘s conception of punishment was heavily influenced by Dante‘s medieval epic, The Divine Comedy. The connection between the two works, while recognizable, can often be quite puzzling. Further research demonstrates how Milton expertly incorporates Dante‘s Comedia into his own while also substantiating that influence within Milton‘s epic. i To Laura Knoppers, for all the hours of guidance and attention she committed to this project. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract………………………………………………………i Acknowledgements …………………………………………ii Introduction …………………………………………………1 Dante‘s Understanding of Punishment in the Inferno ……....4 Milton‘s Scheme of Punishment in Paradise Lost ……......14 The Issue of Repentance in Paradise Lost…………………21 Conclusion ………………………………………………...27 Works Cited …………...…………………………………..28 In the opening invocation to his epic, Paradise Lost,1 John Milton asserts the aim of the poem to ―justify the ways of God to men‖ (PL I.26). The ―ways‖ to which Milton is referring are God‘s punishments of mankind and of Satan as a result of their disobedience for which each will lose his paradise. -

The Adventures of Tom Sawyer

1 THE ADVENTURES OF TOM SAWYER BY MARK TWAIN (Samuel Langhorne Clemens) Published by Ichthus Academy The Adventures of Tom Sawyer ©Ichthus Academy 2 CONTENTS Chapter I 5 Chapter II 13 Chapter III 18 Chapter IV 23 Chapter V 31 Chapter VI 35 Chapter VII 46 Chapter VIII 52 Chapter IX 57 Chapter X 63 Chapter XI 69 Chapter XII 73 Chapter XIII 77 Chapter XIV 84 Chapter XV 89 Chapter XVI 93 Chapter XVII 101 Chapter XVIII 104 Chapter XIX 112 Chapter XX 115 Chapter XXI 119 Chapter XXII 124 The Adventures of Tom Sawyer ©Ichthus Academy 3 Chapter XXIII 127 Chapter XXIV 133 Chapter XXV 134 Chapter XXVI 141 Chapter XXVII 149 Chapter XXVIII 152 Chapter XXIX 155 Chapter XXX 161 Chapter XXXI 169 Chapter XXXII 177 Chapter XXXIII 180 Chapter XXXIV 189 Chapter XXXV 192 The Adventures of Tom Sawyer ©Ichthus Academy 4 PREFACE Most of the adventures recorded in this book really occurred; one or two were experiences of my own, the rest those of boys who were schoolmates of mine. Huck Finn is drawn from life; Tom Sawyer also, but not from an individual—he is a combination of the characteristics of three boys whom I knew, and therefore belongs to the composite order of architecture. The odd superstitions touched upon were all prevalent among children and slaves in the West at the period of this story—that is to say, thirty or forty years ago. Although my book is intended mainly for the entertainment of boys and girls, I hope it will not be shunned by men and women on that account, for part of my plan has been to try to pleasantly remind adults of what they once were themselves, and of how they felt and thought and talked, and what queer enterprises they sometimes engaged in. -

A Little Boy Lost and Various Poems a Little Boy Lost Together with the Poems of W

THIS EDITION IS LIMITED TO 75O COPIES FOR SALE IN ENGLAND, IOO FOR SALE IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, AND 35 PRESENTATION COPIES THE COLLECTED WORKS of W. H. HUDSON IN TWENTY-FOUR VOLUMES A LITTLE BOY LOST AND VARIOUS POEMS A LITTLE BOY LOST TOGETHER WITH THE POEMS OF W. H. HUDSON M C M X X111 LONDON y TORONTO J. M. DENT & SONS LTD. NEW YORK: E. P. DUTTON CO. All righís reserved PRINTED IN GREAT BRITAIN NOTE It has been thought desirable that the small contení of W. H. Hudson’s verse writings be assembled in one book, and to the story of A Little Boy Lost in this volunte the Publishers have appended all such authentic poems as can be found. Of these the most important, the bailad of The Oíd Man of Kensington Gardens, is here made public for the first time. CONTENTS A LITTLE BOY LOST CHAP. PACE I. The Home on the Great Plain . i II. The Spoonbill and the Cloud . 7 III. Chasing a Flying Figure .... 14 IV. Martin is Found by a Deaf Old Man . 18 V. The People of the Mirage ... 27 VI. Martin meets with Savages .... 40 VII. Alone in the Great Forest .... 48 VIII. The Flower and the Serpent ... 54 IX. The Black People of the Sky . 62 X. A Troop of Wild Horses . 71 XI. The Lady of the Hills ..... 83 XII. The Little People Underground ... 89 XIII. The Great Blue Water. 98 XIV. The Wonders of the Hills . 104 XV. Martin’s Eyes are Opened . -

THE ADVENTURES of TOM SAWYER by MARK TWAIN (Samuel Langhorne Clemens)

THE ADVENTURES OF TOM SAWYER BY MARK TWAIN (Samuel Langhorne Clemens) A FREE E-BOOK: TRW STORIES TRWHEELER.COM/EBOOKS.HTML CONTENTS A Free E-Book: TRW Stories trwheeler.com/ebooks.html .................................................... 1 Contents ........................................................................................................................................ 1 Part 1 .............................................................................................................................................. 3 PREFACE ................................................................................................................................... 4 CHAPTER I ............................................................................................................................... 5 CHAPTER II ............................................................................................................................ 15 CHAPTER III ........................................................................................................................... 21 Part 2 ............................................................................................................................................ 28 CHAPTER IV .......................................................................................................................... 29 CHAPTER V ............................................................................................................................ 39 CHAPTER VI ......................................................................................................................... -

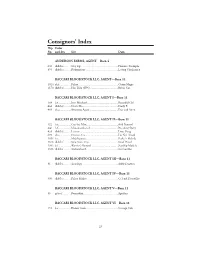

Consignors' Index

Consignors’ Index Hip Color No. and Sex Sire Dam ANDERSON FARMS, AGENT—Barn 4 643 dkb/b.f. .........City Zip ..................................................Helena’s Triomphe 859 dkb/b.c. .........Bodemeister ............................................Loving Vindication BACCARI BLOODSTOCK LLC, AGENT—Barn 11 1024 ch.f. ...............Palace ......................................................Ocean Magic 1170 dkb/b.f. .........Hat Trick (JPN) ......................................Reba’s Cat BACCARI BLOODSTOCK LLC, AGENT I—Barn 11 188 b.f..................Into Mischief ...........................................Beautiful Girl 464 dkb/b.f. .........Uncle Mo ................................................Emily B 484 ch.c. ..............Awesome Again .......................................Ever and Anon BACCARI BLOODSTOCK LLC, AGENT II—Barn 11 122 b.c. ................Can the Man ...........................................And Beyond 246 b.f..................Misremembered ......................................Broadway Baby 424 dkb/b.f. .........Liaison ....................................................Dixie Bang 695 ch.c. ..............Discreet Cat ............................................I’m Not Afraid 1073 b.c. ................Midshipman ............................................Peeker’s Melody 1318 dkb/b.f. .........New Year’s Day ........................................Snuff Hazel 1362 b.f..................Warrior’s Reward .....................................Starship Made It 1366 dkb/b.f. .........Archarcharch ...........................................Steel