Charles Sheeler; Modernism, Precisionism and the Borders Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cubism in America

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Sheldon Museum of Art Catalogues and Publications Sheldon Museum of Art 1985 Cubism in America Donald Bartlett Doe Sheldon Memorial Art Gallery Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/sheldonpubs Part of the Art and Design Commons Doe, Donald Bartlett, "Cubism in America" (1985). Sheldon Museum of Art Catalogues and Publications. 19. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/sheldonpubs/19 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Sheldon Museum of Art at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Sheldon Museum of Art Catalogues and Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. RESOURCE SERIES CUBISM IN SHELDON MEMORIAL ART GALLERY AMERICA Resource/Reservoir is part of Sheldon's on-going Resource Exhibition Series. Resource/Reservoir explores various aspects of the Gallery's permanent collection. The Resource Series is supported in part by grants from the National Endowment for the Arts. A portion of the Gallery's general operating funds for this fiscal year has been provided through a grant from the Institute of Museum Services, a federal agency that offers general operating support to the nation's museums. Henry Fitch Taylor Cubis t Still Life, c. 19 14, oil on canvas Cubism in America .".. As a style, Cubism constitutes the single effort which began in 1907. Their develop most important revolution in the history of ment of what came to be called Cubism art since the second and third decades of by a hostile critic who took the word from a the 15th century and the beginnings of the skeptical Matisse-can, in very reduced Renaissance. -

MSA 7 Program (Draft 10.17)

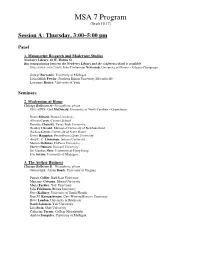

MSA 7 Program (Draft 10.17) Session A: Thursday, 3:00–5:00 pm Panel 1. Manuscript Research and Modernist Studies Newberry Library, 60 W. Walton St. Bus transportation between the Newberry Library and the conference hotel is available ORGANIZER AND CHAIR: John Timberman Newcomb, University of Illinois – Urbana-Champaign George Bornstein, University of Michigan Laura Milsk Fowler, Southern Illinois University Edwardsville Lawrence Rainey, University of York Seminars 2. Modernism at Home Chicago Ballroom A—No auditors, please ORGANIZER: Gail McDonald, University of North Carolina – Greensboro Dawn Blizard, Brown University Allison Carey, Cannon School Dorothy Chansky, Texas Tech University Bradley Clissold, Memorial University of Newfoundland Barbara Green, University of Notre Dame Kevin Hagopian, Pennsylvania State University Amy E. C. Linneman, Indiana University Marion McInnes, DePauw University Phoebe Putnam, Harvard University Jin Xiaotian Skye, University of Hong Kong Eve Sorum, University of Michigan 3. The Author Business Chicago Ballroom B—No auditors, please ORGANIZER: Alison Booth, University of Virginia Patrick Collier, Ball State University Marianne Cotugno, Miami University Maria Fackler, Yale University Julia Friedman, Brown University Peter Kalliney, University of South Florida Kurt M. Koenigsberger, Case Western Reserve University Bette London, University of Rochester Randi Saloman, Yale University Lisa Stein, Ohio University Catherine Turner, College Misericordia Andrea Zemgulys, University of Michigan 4. Anthropological -

Pressionism,Which Was Haven't Lookedat in a Long Time," Stillgoing Strongafter Maciejunessaid "It's Interestingto See World Wari

+ aynm Feran "Precisionism in DispatchEntertainment Reporter America■ 1915-1941: ReorderingReality" N 1915, ARTISTMARcEL DUCHAMP will openSunday proclaimedthe UnitedStates and continue "thecountry of theart of the throughJuly 4 at future." the Columbus "Look atthe skyscrapers!"he Museum of Art, said"Has Europe anything to 480 E. BroadSt. show more beautifulthan these?" Tourswill begiven The Frenchman's words at noonMay 26 and focusedattention on what was June 16, and 2 p.m. e seen as auniquely American artistic May 28and June movement. 18. Call 221-6801. "Precisionismin America1915-1941: ReorderingReality" is "thefirst major study of precisionismin a long time,"said NannetteMaciejunes, seniorcurator at the ColumbusMuseum of Art. "Precisionismis verytied up withthe search for a ABoVE:The cleanlines of rural unique Americanidentity," scenes: Bucks OHmJy Barn(1918) t she said"It wasabout the " by Charles Sheeler(1883-1965) tyingof a ruralpast to the mechanicalfuture. A lot of LEFT:The forms of the machine • people in the'.20s called it agewith classicalclarity: A.ugussin 'thetrue American art.' " andNu:oletle (1923)by Charles By the timeprecisionism Demuth (1883-1935) arrived,the United States waswell on itsway froma - ruralsociety to a nationof show,which began at theMontclair Art 0 big citieswith skyscrapers Museumin New Jerseyand features andhomes withmodern works by 26 artistsfrom almost 30 I marvelssuch asvacuum institutionsand private collections. cleanersand washing "Thisshow is so criticalto us," � �es. Maciejunes said"(Ferdinand) Rowald !'!. Painters and was majora collector in thisarea. He saw photographersassociated theparallel between cubism and �� withprecisionism included precisionism, andhe collected both." iii CharlesDemuth, Morton Althoughmany works in theNew I Scharnberg,Charles Sheeler Jerseyexhibition are not availablefor the s andJoseph Stella. -

Edward Hopper's Adaptation of the American Sublime

Rhetoric and Redress: Edward Hopper‘s Adaptation of the American Sublime A thesis presented to the faculty of the College of Fine Arts of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Fine Arts Rachael M. Crouch August 2007 This thesis titled Rhetoric and Redress: Edward Hopper’s Adaptation of the American Sublime by RACHAEL M. CROUCH has been approved for the School of Art and the College of Fine Arts by Jeannette Klein Assistant Professor of Art History Charles A. McWeeny Dean, College of Fine Arts Abstract CROUCH, RACHAEL M., M.F.A., August 2007, Art History Rhetoric and Redress: Hopper’s Adaptation of the American Sublime (80 pp.) Director of Thesis: Jeannette Klein The primary objective of this thesis is to introduce a new form of visual rhetoric called the “urban sublime.” The author identifies certain elements in the work of Edward Hopper that suggest a connection to earlier American landscape paintings, the pictorial conventions of which locate them within the discursive formation of the American Sublime. Further, the widespread and persistent recognition of Hopper’s images as unmistakably American, links them to the earlier landscapes on the basis of national identity construction. The thesis is comprised of four parts: First, the definitional and methodological assumptions of visual rhetoric will be addressed; part two includes an extensive discussion of the sublime and its discursive appropriation. Part three focuses on the American Sublime and its formative role in the construction of -

Knife Grinder Date: 1912-1913 Creator: Umberto Boccioni, Italian, 1882-1916 Title: Dynamism of a Soccer Player Work Type: Painting Date: 1913 Cubo-Futurism

Creator: Malevich, Kazimir, Russian, 1878- 1935 Title: Knife Grinder Date: 1912-1913 Creator: Umberto Boccioni, Italian, 1882-1916 Title: Dynamism of a Soccer Player Work Type: Painting Date: 1913 Cubo-Futurism • A common theme I have been seeing in the different Cubo- Futurism Paintings is a wide variety of color and either solid formations or a high amount of single colors blended or layered without losing the original color. I sense of movement is also very big, the Knife Grinder shows the action of grinding by a repeated image of the hand, knife, or foot on paddle to show each moment of movement. The solid shapes and designs tho individually may not seem relevant to a human figure all come together to show the act of sharpening a knife. I Love this piece because of the strong colors and repeated imagery to show the act. • In the Dynamism of a soccer player the sense of movement is sort of around and into the center, I can imagine a great play of lights and crystal clarity of the ideas of the objects moving. I almost feel like this is showing not just one moment or one movement but perhaps an entire soccer game in the scope of the 2D canvas. Creator: Demuth, Charles, 1883-1935 Title: Aucassin and Nicolette Date: 1921 Creator: Charles Demuth Title: My Egypt Work Type: Paintings Date: 1927 Precisionism • Precisionism is the idea of making an artwork of another “artwork” as in a piece of architecture , or machinery. The artist renders the structure using very geometric and precise lines and they tend to keep an element of realism in their work. -

Guggenheim Museum Archives Reel-To-Reel Collection “Post Object Sculpture” with Jack Burnham, 1967 Good Afternoon, Ladies An

Guggenheim Museum Archives Reel-to-Reel collection “Post Object Sculpture” with Jack Burnham, 1967 MALE 1 Good afternoon, ladies and gentlemen, and welcome to the third in a series of lectures on contemporary sculpture, presented by the museum on the occasion of the Fifth Guggenheim International Exhibition. Today’s lecture is by Mr. Jack Wesley Burnham. Mr. Burnham is an individual who combines the extraordinary qualities of being both artist and scientist, as well as writer. He was born in 1931 in New York City. He studied at the Boston Museum School, at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. He holds an engineering degree. He holds the degrees of Bachelor of Fine Arts and Master of Fine Arts from Yale University, at which institution he was on the faculty. [00:01:00] And he’s at present a professor at Northwestern University. He is the author of a major new study of modern sculpture, to be published next year by Braziller in New York, entitled Beyond Modern Sculpture. His lecture today is entitled, “Post-Object Sculpture.” After the lecture, there will be a short question-and-answer period. Mr. Burnham. JACK BURNHAM Mr. [Fry?], I’d like to thank you for inviting me. And I’d like to [00:02:00] thank all of you for being here today. I’m going to read part of this lecture, and part of it will be fairly extemporaneous. But I’d like to begin by saying that I find the task of speaking on post- object sculpture difficult for two reasons. First, because the rationale behind object sculpture and the art form itself have developed to such a sophisticated degree in the past two years. -

Methods for Modernism: American Art, 1876-1925

METHODS FOR MODERNISM American Art, 1876-1925 METHODS FOR MODERNISM American Art, 1876-1925 Diana K. Tuite Linda J. Docherty Bowdoin College Museum of Art Brunswick, Maine This catalogue accompanies two exhibitions, Methods for Modernism: Form and Color in American Art, 1900-192$ (April 8 - July 11, 2010) and Learning to Paint: American Artists and European Art, 1876-189} (January 26 - July 11, 20io) at the Bowdoin College Museum of Art, Brunswick, Maine. This project is generously supported by the Yale University Art Gallery Collection- Sharing Initiative, funded by the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation; a grant from the American Art Program of the Henry Luce Foundation; an endowed fund given by the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation; and Bowdoin College. Design: Katie Lee, New York, New York Printer: Penmor Lithographers, Lewiston, Maine ISBN: 978-0-916606-41-1 Cover Detail: Patrick Henry Bruce, American, 1881-1936, Composition 11, ca. 1916. Gift of Collection Societe Anonyme, Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven, Connecticut. Illustrated on page 53. Pages 8-9 Detail: John Singer Sargent, American, 1856-1925, Portrait of Elizabeth Nelson Fairchild, 1887. Museum Purchase, George Otis Hamlin Fund and Friends of the College Fund, Bowdoin College Museum of Art. Illustrated on page 18. Pages 30-31 Detail: Manierre Dawson, American, 1887-1969, Untitled, 1913. Gift of Dr. Lewis Obi, Mr. Lefferts Mabie, and Mr. Frank J. McKeown, Jr., Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven, Connecticut. Illustrated on page 32. Copyright © 2010 Bowdoin College Table of Contents FOREWORD AND ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Kevin Salatino LEARNING TO PAINT: 10 AMERICAN ARTISTS AND EUROPEAN ART 1876-1893 Linda J. -

Harn Museum of Art Instructional Resource: Thinking About Modernity

Harn Museum of Art Instructional Resource: Thinking about Modernity TABLE OF CONTENTS “Give Me A Wilderness or A City”: George Bellows’s Rural Life ................................................ 2 Francis Criss: Locating Monuments, Locating Modernity ............................................................ 6 Seeing Beyond: Approaches to Teaching Salvador Dalí’s Appollinaire ............................. 10 “On the Margins of Written Poetry”: Pedro Figari ......................................................................... 14 Childe Hassam: American Impressionist and Preserver of Nature ..................................... 18 Subtlety of Line: Palmer Hayden’s Quiet Activism ........................................................................ 22 Modernist Erotica: André Kertész’s Distortion #128 ................................................................... 26 Helen Levitt: In the New York City Streets ......................................................................................... 31 Happening Hats: Pierre-Auguste Renoir’s Le chapeau épinglé .............................................. 35 Diego Rivera: The People’s Painter ......................................................................................................... 39 Diego Rivera: El Pintor del Pueblo ........................................................................................................... 45 Household Modernism, Domestic Arts: Tiffany’s Eighteen-Light Pond Lily Lamp .... 51 Marguerite Zorach: Modernism’s Tense Vistas .............................................................................. -

F Or the Fiscal Year Ending June 3 0 , 2 0 18

FOR THE FISCAL YEAR ENDING JUNE 30, 2018 annual report The Year in Summary As the largest public arts institution in Northern California, the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, comprising the de Young and the Legion of Honor, pursue the mission of serving a broad de Young and diverse constituency with exhibitions and programs that 50 Hagiwara Tea Garden Drive San Francisco, CA 94118 inform, educate, inspire, and entertain. In the past year, the deyoungmuseum.org Museums’ staff actively worked to achieve this mission with the dedicated support of members, donors, corporate and foundation Legion of Honor partners, trustees, city leaders, and the community at large. 100 34th Avenue One primary strategy in fulfilling the Museums’ purpose is in San Francisco, CA 94121 legionofhonor.org strengthening the permanent collection, then drawing from these rich resources to organize extraordinary exhibitions. Between 2 ANNUAL REPORT 2017–2018 “He never stopped making paintings and sculpture, generally at a scale one might call, at the very least, ambitious. Now San Francisco’s Legion of Honor has provided a space that matches in size the artist’s aspiration.” —San Francisco Chronicle \ on Julian Schnabel: Symbols of Actual Life “A lavish romp through the Rococo.” —Wall Street Journal \ on Casanova: The Seduction of Europe “A groundbreaking show like this may not appear again in July 2017 and June 2018, the Museums organized nearly thirty North America soon.” special exhibitions and installations. At the de Young, these — Fine Art Connoisseur \ included Teotihuacan: City of Water, City of Fire, the result of a on Truth and Beauty: long-term collaboration with cultural partners in Mexico, which The Pre-Raphaelites and presented examples from the Museums’ outstanding holdings the Old Masters of Teotihuacan murals—the largest and most important such collection outside Mexico. -

“Just What Was It That Made U.S. Art So Different, So Appealing?”

“JUST WHAT WAS IT THAT MADE U.S. ART SO DIFFERENT, SO APPEALING?”: CASE STUDIES OF THE CRITICAL RECEPTION OF AMERICAN AVANT-GARDE PAINTING IN LONDON, 1950-1964 by FRANK G. SPICER III Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Dissertation Adviser: Dr. Ellen G. Landau Department of Art History and Art CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY May, 2009 CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES We hereby approve the thesis/dissertation of Frank G. Spicer III ______________________________________________________ Doctor of Philosophy candidate for the ________________________________degree *. Dr. Ellen G. Landau (signed)_______________________________________________ (chair of the committee) ________________________________________________Dr. Anne Helmreich Dr. Henry Adams ________________________________________________ Dr. Kurt Koenigsberger ________________________________________________ ________________________________________________ ________________________________________________ December 18, 2008 (date) _______________________ *We also certify that written approval has been obtained for any proprietary material contained therein. Table of Contents List of Figures 2 Acknowledgements 7 Abstract 12 Introduction 14 Chapter I. Historiography of Secondary Literature 23 II. The London Milieu 49 III. The Early Period: 1946/1950-55 73 IV. The Middle Period: 1956-59: Part 1, The Tate 94 V. The Middle Period: 1956-59: Part 2 127 VI. The Later Period: 1960-1962 171 VII. The Later Period: 1963-64: Part 1 213 VIII. The Later Period: 1963-64: Part 2 250 Concluding Remarks 286 Figures 299 Bibliography 384 1 List of Figures Fig. 1 Richard Hamilton Just What Is It That Makes Today’s Homes So Different, So Appealing? (1956) Fig. 2 Modern Art in the United States Catalogue Cover Fig. 3 The New American Painting Catalogue Cover Fig. -

Charles Sheeler

CHARLES SHEELER PHOTOGRAPHER AT THE METROPOLITAN MUSEUM OF ART NEW YORK 1982 1 The photographs were printed from Charles Sheeler's original negatives by Alan B. Newman on Strathmore drawing paper, hand coated with light-sensitive salts of platinum and palladium; Mr. Newman coordinated production for the project. The design and letterpress printing, on Rives BFK (France), are by Carol J. Blinn, who also designed the portfolio case in the Dutch linens Brillianta and Halflinnen. Typesetting in Dante monotype is by Michael and Winifred Bixler. The case was manufactured by Lisa Callaway. This portfolio is limited to an edition of two hundred fifty, numbered 1/250 through 250/250, and twenty-five artist's proofs. Photographs and text copyright © 1982 by The Metropolitan Museum of Art Title page photograph by Charles Sheeler for the Metropolitan Museum of Art Annual Report, 1942. * "0 5 FOREWORD THIS GROUP OF PHOTOGRAPHS by Charles Sheeler focuses our attention on the distinction between photography as art and art as photography. Sheeler was not the first to note this de- markation. The earliest American, British, and French photographers looked to painting and sculpture as the starting points for their own creativity. Our 1840s South worth and Hawes portrait of an unidentified girl standing beside a portrait of George Washington (37.14.53) is an early example of the photographer using traditional art as a starting point. Remarkable as it may sound, works of art are experienced by more people through photo graphs and reproductions of photographs than they are by people standing in front of objects or paintings and observing them with their own eyes. -

Schamberg Machine Composition Fact Sheet

MORTON LIVINGSTON SCHAMBERG (1881 - 1918) Machine Composition, c.1915-16 pastel and pencil on paper 5 1/2 x 8 inches Provenance The Artist Alexander Cokos, Pennsylvania David Schaff Sid Deutsch Gallery, New York Forum Gallery, New York Alice and Marvin Sinkoff, New York (1985-2002) By descent from the above (until 2007) Martha Parrish & James Reinish, Inc., New York Private Collection, New York (acquired directly from the above, 2007) Exhibited Sid Deutsch Gallery, New York, NY Forum Gallery, New York, NY, 1985 A Point of View: 20th Century American Art from a Long Island Collection, The Heckscher Museum, Huntington, NY, September 8 – November 4, 1990 Every Day Mysteries: Modern and Contemporary Still Life, DC Moore Gallery, New York, NY, March 18 – May 1st, 2004 Martha Parrish & James Reinish, Inc., New York, NY Literature Noll, Anna C., A Point of View: 20th Century American Art from a Long Island Collection, The Heckscher Museum, Huntington, NY, 1990, p. 18, cat. 67, Illustrated, and p. 47, Listed. Essay Morton Livingston Schamberg remains one of the most elusive figures of early American Modernism. He participated in the most extreme edge of the American vanguard, promoting aesthetic and conceptual values which were only beginning to be understood in the United States. Dealers, collectors, and critics alike who by the mid-1910s were gradually accepting Cubism and who admired Schamberg’s work were not able to fully understand his imagery, as evidenced in Henry McBride’s eloquent eulogy. * Schamberg was a machine-age modernist even before Charles Sheeler began to pay homage in his own art to American industry and manufacturing.