BERTHOLLET and the EGYPTIAN NATRON Hamed A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

When “Evaporites” Are Not Formed by Evaporation: the Role Of

When “evaporites” are not formed by evaporation: The role of temperature and pCO2 on saline deposits of the Eocene Green River Formation, Colorado, USA Robert V. Demicco† and Tim K. Lowenstein Department of Geological Sciences and Environmental Studies, Binghamton University, Binghamton, New York 13902-6000, USA ABSTRACT INTRODUCTION rated with halite. During summer, the waters of the lake above the thermocline (at <25 m depth) Halite precipitates in the Dead Sea during Geologists studying salt deposits have noticed warm to ∼34 °C, become undersaturated with ha- winter but re-dissolves above the thermo- that very soluble minerals that occur in the cen- lite due to the temperature increase, and the bulk cline upon summer warming, “focusing” ha- ter of a basin do not extend out to the edges of of the winter-deposited halite above the thermo- lite deposition below the thermocline (Sirota the basin (Hsü et al., 1973; Dyni, 1981; Lowen- cline re-dissolves. Summer dissolution of halite et al., 2016, 2017, 2018). Here we develop an stein, 1988). This is true even where: (1) soluble occurs in the Dead Sea despite any increase in “evaporite focusing” model for evaporites salts are interpreted to have been deposited in evaporative concentration at the surface. The ha- (nahcolite + halite) preserved in a restricted a deep evaporitic lake or marine basin and (2) lite that settled into the deeper, cooler isothermal area of the Eocene Green River Formation deep-water deposits that encase salts in the cen- bottom waters, however, accumulates as an an- in the Piceance Creek Basin of Colorado, ter of the basin can be confidently traced to pe- nual layer at depths below the 25 m deep ther- USA. -

SODIUM BICARBONATE (NAHCOLITE) from COLORADOOIL SHALE1 Tbr-R-Enrr-2

SODIUM BICARBONATE (NAHCOLITE) FROM COLORADOOIL SHALE1 TBr-r-Enrr-2 Assrnact Sodium bicarbonate (nahcolite) was found in the high-grade oil-shale zone of tfre Para- chute Creek member of the Eocene Green River formation in ttre underground development openings of ttre Bureau of Mines Oil-Shale Demonstration Mine at Anvil Points, 10 miles west of Rifle, Colo. It occurs as concretions varying up to five feet in diameter and as layers up to four inches thick, intercalated between rich oil-shale beds. It is suggested tlat the concretions were formed while the ooze, which had been deposited in the bottom of the former Uinta Lake, was still soft and plastic. INrnorucrrorq Natural sodium bicarbonate (NaHCOa) was reported first by P. Wal- thera from Little Magadi dry lake, in British East Africa, but no con- flmatory evidence was given. F. A. Bannister,a who reported natural sodium bicarbonate in an efforescencefrom an old Roman underground conduit from hot springs at Stufe de Nerone, near Naples, gave the min- eral the name "nahcolite." Later the mineral was reported by E. Quer- cighs as an incrustation in a lava grotto, apparently mixed with thenar- dite and halite. Large quantities of nahcolite were found in a well core- dritled below the central salt crust of Searles Lake and described by William F. Foshag.6 The presenceof saline phasesin the eastern part of the Uinta Basin in the high-grade oil-shale facies of the Parachute Creek member of the Eocene Green Eiver formation was noted by W. H. Bradley.T He states that ellipsoidal cavities whose major axes range from a fraction of an inch to more than five feet in length contained molds of radial aggregates of a saline mineral that could not be determined becauseof the complex intergrowth of the crystal molds. -

Teaching Chemistry in the French Revolution 251

Teaching Chemistry in the French Revolution 251 Chapter 10 Teaching Chemistry in the French Revolution: Pedagogy, Materials and Politics Bernadette Bensaude Vincent By the end of 1794 – Year III of the revolutionary calendar, the young “one and indivisible” French republic established a Normal School (École normale) to “provide the French people with a system of instruction worthy of its novel destiny.”1 More concretely the purpose was to train a number of citizens quickly so that they could train the future primary and secondary teachers in all the districts of the French territory. Chemistry was an integral part of the curriculum, which included both science and humanities. The term ‘école normale’ clearly conveys a project of normalization or standardization of edu- cation providing a uniform approach to all the sectors of knowledge previously covered by the Encyclopédie. This teaching institution was dedicated to “shap- ing the man and the citizen.” It was meant to coproduce knowledge and citizenship according to the republican ideals of liberty, equality, and frater- nity. Well-trained teachers (instituteurs) would be “capable of being the executives of a plan aimed at regenerating the human understanding in a republic of 25 million people, all of whom democracy rendered equal.”2 Claude-Louis Berthollet participated in this state initiative to assume his social and political role as a teacher. As one of the supporters of Lavoisier’s chemistry and a member of the group of academicians who reformed the 1 Anon., “Arrêté des représentants du peuple près les Écoles normales du 24 nivôse an III de la République française une et indivisible,” Séances des Écoles normales (Paris: Imprimerie du Cercle social, 1800-1801). -

Statecraft and Insect Oeconomies in the Global French Enlightenment (1670-1815)

Statecraft and Insect Oeconomies in the Global French Enlightenment (1670-1815) Pierre-Etienne Stockland Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2018 © 2017 Etienne Stockland All rights reserved ABSTRACT Statecraft and Insect Oeconomies in the Global French Enlightenment (1670-1815) Pierre-Etienne Stockland Naturalists, state administrators and farmers in France and its colonies developed a myriad set of techniques over the course of the long eighteenth century to manage the circulation of useful and harmful insects. The development of normative protocols for classifying, depicting and observing insects provided a set of common tools and techniques for identifying and tracking useful and harmful insects across great distances. Administrative techniques for containing the movement of harmful insects such as quarantine, grain processing and fumigation developed at the intersection of science and statecraft, through the collaborative efforts of diplomats, state administrators, naturalists and chemical practitioners. The introduction of insectivorous animals into French colonies besieged by harmful insects was envisioned as strategy for restoring providential balance within environments suffering from human-induced disequilibria. Naturalists, administrators, and agricultural improvers also collaborated in projects to maximize the production of useful substances secreted by insects, namely silk, dyes and medicines. A study of -

Claude Louis Berthollet (1748-1822) Was After Lavoisier One of the Most

Our Academic Ancestors It is hard to overlook the fact that our faculty, for the most part, are academically descended from three men: Berthollet, Berzelius, and Fourcroy. (There is disagreement as to whether those who preceded them, going back to Paracelsus, were truly chemists.) Presenting brief biographies of the three is an on-going project. Claude Louis Berthollet (1748-1822) He was after Lavoisier one of the most distinguished French chemists of his time Berthollet had, according to Weller (1999) “determined the composition of ammonia in 1785, prussic acid in 1787, and hydrogen sulfide in 1789. Berthollet pointed out that the absence of oxygen in HCN and H2S disproved Lavoisier’s hypothesis that all acids contain oxygen.” Berthollet was also a friend and confident of Napoleon Bonaparte (1869-1821), and was one of the savants who went with Napoleon on the Egyptian campaign in 1998. He was the organizer of a “Committee on the Arts and Sciences” that accompanied the army. The expedition was a military failure because the French fleet was destroyed at the battle of Aboukir Bay (on August 1, 1798) by a British fleet under the leadership of Admiral Sir Horatio Nelson. Among Berthollet’s assignments in Egypt was finding fuel for bread ovens, obtaining substitutes for hops for making beer, and obtaining raw materials for making gun powder (Weller, 1999). Another special assignment involved investigating a set of small lakes 45 miles northwest of Cairo. The shoreline of the Natron lakes had a crust of natron, hydrated sodium carbonate. Berthollet recognized that he had seen a unique occurrence. -

Lake Chad Basin

Integrated and Sustainable Management of Shared Aquifer Systems and Basins of the Sahel Region RAF/7/011 LAKE CHAD BASIN 2017 INTEGRATED AND SUSTAINABLE MANAGEMENT OF SHARED AQUIFER SYSTEMS AND BASINS OF THE SAHEL REGION EDITORIAL NOTE This is not an official publication of the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA). The content has not undergone an official review by the IAEA. The views expressed do not necessarily reflect those of the IAEA or its Member States. The use of particular designations of countries or territories does not imply any judgement by the IAEA as to the legal status of such countries or territories, or their authorities and institutions, or of the delimitation of their boundaries. The mention of names of specific companies or products (whether or not indicated as registered) does not imply any intention to infringe proprietary rights, nor should it be construed as an endorsement or recommendation on the part of the IAEA. INTEGRATED AND SUSTAINABLE MANAGEMENT OF SHARED AQUIFER SYSTEMS AND BASINS OF THE SAHEL REGION REPORT OF THE IAEA-SUPPORTED REGIONAL TECHNICAL COOPERATION PROJECT RAF/7/011 LAKE CHAD BASIN COUNTERPARTS: Mr Annadif Mahamat Ali ABDELKARIM (Chad) Mr Mahamat Salah HACHIM (Chad) Ms Beatrice KETCHEMEN TANDIA (Cameroon) Mr Wilson Yetoh FANTONG (Cameroon) Mr Sanoussi RABE (Niger) Mr Ismaghil BOBADJI (Niger) Mr Christopher Madubuko MADUABUCHI (Nigeria) Mr Albert Adedeji ADEGBOYEGA (Nigeria) Mr Eric FOTO (Central African Republic) Mr Backo SALE (Central African Republic) EXPERT: Mr Frédèric HUNEAU (France) Reproduced by the IAEA Vienna, Austria, 2017 INTEGRATED AND SUSTAINABLE MANAGEMENT OF SHARED AQUIFER SYSTEMS AND BASINS OF THE SAHEL REGION INTEGRATED AND SUSTAINABLE MANAGEMENT OF SHARED AQUIFER SYSTEMS AND BASINS OF THE SAHEL REGION Table of Contents 1. -

Wt/Tpr/S/285 • Chad

WT/TPR/S/285 • CHAD - 369 - ANNEX 5 CHAD WT/TPR/S/285 • CHAD - 370 - CONTENTS 1 ECONOMIC ENVIRONMENT ...................................................................................... 373 1.1 Main features ......................................................................................................... 373 1.2 Recent economic developments ................................................................................ 375 1.3 Trends in trade and investment ................................................................................ 376 1.4 Outlook ................................................................................................................. 379 2 TRADE AND INVESTMENT REGIMES ......................................................................... 380 2.1 Overview ............................................................................................................... 380 2.2 Trade policy objectives ............................................................................................ 383 2.3 Trade agreements and arrangements ........................................................................ 383 2.3.1 World Trade Organization ...................................................................................... 383 2.3.2 Relations with the European Union ......................................................................... 384 2.3.3 Relations with the United States ............................................................................ 384 2.3.4 Other agreements ............................................................................................... -

HYDROGEOCHEMICAL CONDITION of the PIKROLIMNI LAKE (KILKIS GREECE) Dotsika E.1, Maniatis Y.1 , Tzavidopoulos E.1, Poutoukis D.2 and Albanakis K.3

∆ελτίο της Ελληνικής Γεωλογικής Εταιρίας τοµ. XXXVI, 2004 Bulletin of the Geological Society of Greece vol. XXXVI, 2004 Πρακτικά 10ου ∆ιεθνούς Συνεδρίου, Θεσ/νίκη Απρίλιος 2004 Proceedings of the 10th International Congress, Thessaloniki, April 2004 HYDROGEOCHEMICAL CONDITION OF THE PIKROLIMNI LAKE (KILKIS GREECE) Dotsika E.1, Maniatis Y.1 , Tzavidopoulos E.1, Poutoukis D.2 and Albanakis K.3. 1 Inst.of Material science, N.C.S.R. «Demokritos», Aghia Paraskevi, Attiki 2 General secretary Research and Technology, Mesogion 12-14, Athens 3 School of Geology, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki ABSTRACT In order to understand the hydrogeochemical conditions of the basin of Pikrolimni we collected water samples from the borehole in the thermal spa of Pikrolimni and samples of brine and sediments from the lake. We also sampled fresh water of the region. The depth of the borehole in the thermal spa is approximately 250 meters. This water is naturally sparkling, with a metallic aftertaste and a slight organic smell. The samples were taken twice during the year: in summer (8/2002) and in winter (2003). The analytical scheme includes field measurements of temperature, conductivity and pH. + + 2+ 2+ - - 2- 2- - - - - Major ions (Na , K , Ca , Mg , Cl , Br , SO4 , CO3 , HCO3 , NO3 ), F and Br were determined, in laboratory, according to standard analytical methods. Samples were also subjected to isotopic analysis of δ18O and δ2H. The results from the chemical analyses of the samples, show that the waters taken from the borehole, are of the type Mg- (Na-Ca)-HCO3 and the salts of the lake are of the type Na-Cl- (CO3- SO4). -

Hydrochemical.Pdf

Bulletin of the Geological Society of Greece Vol. 36, 2004 HYDROGEOCHEMICAL CONDITION OF THE PIKROLIMNI LAKE (KILKIS GREECE) Dotsika E. Inst.of Material science, N.C.S.R. «Demokritos» Maniatis Y. Inst.of Material science, N.C.S.R. «Demokritos» Tzavidopoulos E. Inst.of Material science, N.C.S.R. «Demokritos» Poutoukis D. General secretary Research and Technology Albanakis K. School of Geology, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki https://doi.org/10.12681/bgsg.16618 Copyright © 2018 E. Dotsika, Y. Maniatis, E. Tzavidopoulos, D. Poutoukis, K. Albanakis To cite this article: Dotsika, E., Maniatis, Y., Tzavidopoulos, E., Poutoukis, D., & Albanakis, K. (2004). HYDROGEOCHEMICAL CONDITION OF THE PIKROLIMNI LAKE (KILKIS GREECE). Bulletin of the Geological Society of Greece, 36(1), 192-195. doi:https://doi.org/10.12681/bgsg.16618 http://epublishing.ekt.gr | e-Publisher: EKT | Downloaded at 07/04/2020 09:53:29 | Δελτίο της Ελληνικής Γεωλογικής Εταιρίας τομ XXXVI, 2004 Bulletin of the Geological Society of Greece vol. XXXVI, 2004 Πρακτικά 10ou Διεθνούς Συνεδρίου, Θεσ/νίκη Απρίλιος 2004 Proceedings of the 10th International Congress, Thessaloniki, April 2004 HYDROGEOCHEMICAL CONDITION OF THE PIKROLIMNI LAKE (KILKIS GREECE) Dotsika E.1, Maniatis Y.1 , Tzavidopoulos E.1, Poutoukis D.2 and Albanakis K.3. 11nst.of Material science, N.C.S.R. «Demokritos», Aghia Paraskevi, Attiki 2 General secretary Research and Technology, Mesogion 12-14, Athens 3 School of Geology, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki ABSTRACT In order to understand the hydrogeochemical conditions of the basin of Pikrolimni we collected water samples from the borehole in the thermal spa of Pikrolimni and samples of brine and sediments from the lake. -

Glass Making in the Greco-Roman World Studies in Archaeological Sciences 4

Glass Making in the Greco-Roman World Studies in Archaeological Sciences 4 The series Studies in Archaeological Sciences presents state-of-the-art methodological, technical or material science contributions to Archaeological Sciences. The series aims to reconstruct the integrated story of human and material culture through time and testifies to the necessity of inter- and multidisciplinary research in cultural heritage studies. Editor-in-Chief Prof. Patrick Degryse, Centre for Archaeological Sciences, KU Leuven, Belgium Editorial Board Prof. Ian Freestone, Cardiff Department of Archaeology, Cardiff University, United Kingdom Prof. Carl Knappett, Department of Art, University of Toronto, Canada Prof. Andrew Shortland, Centre for Archaeological and Forensic Analysis, Cranfield University, United Kingdom Prof. Manuel Sintubin, Department of Earth & Environmental Sciences, KU Leuven, Belgium Prof. Marc Waelkens, Centre for Archaeological Sciences, KU Leuven, Belgium Glass Making in the Greco-Roman World Results of the ARCHGLASS Project Edited by Patrick Degryse Leuven University Press Published with support of © 2014 by Leuven University Press / Presses Universitaires de Louvain / Universitaire Pers Leuven. Minderbroedersstraat 4, B-3000 Leuven (Belgium). All rights reserved. Except in those cases expressly determined by law, no part of this publication may be multiplied, saved in an automated datafile or made public in any way whatsoever without the express prior written consent of the publishers. ISBN 978 94 6270 007 9 D / 2014 / 1869 / 86 NUR: 682/933 Lay-out: Friedemann Vervoort Cover: Jurgen Leemans 5 Preface The ARCHGLASS “Archaeometry and Archaeology of Ancient Glass Production as a Source for Ancient Technology and Trade of Raw Materials” project, is a Seventh Framework Programme “Ideas” project funded under the European Research Council Starting Grant scheme. -

Geology of the Area South of Magadi, Kenya

%% %% %% %% %% %% %% %% %% %% %% %% %% %% %% %% %% %% %% %% %% %% %% %% %% %% %% %% %% %% %% %% %% %% %% %% %% %% %% % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % %% % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % %% %% % % % % % % %% %% %% %% %% %% %% %% %% %% %% %% %% %% %% % GEOLOGIC HISTORY % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % Legend % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % %% % %% %% % HOLOCENE % %% %% %% %% %% % % Pl-na %% %% %% % % Alasho ash %% %% %% % Evaporite Series (0-9 ka): trona with interbedded clays. The Magadi Soda Company currently mines the % % % Sediments Metamorphics %% %% %% %% %% %% %% %% %% %% %% %% % trona at Lake Magadi in the region to the north. Samples of this formation from Natron indicate significantly % %% %% %% %% %% %% %% % % Pl-nv %% % % Alasho centers %% %% %% % G% eology of the Area South of Magadi, Kenya more halite than trona compared to Lake Magadi (Bell and Simonetti 1996). %% % % Holocene Kurase Group %% %% %% %% %% %% %% %% %% %% %% %% %% %% %% %% % % % % % Pl-pt % % % % Magadi Trachyte Xl % % % % PLEISTOCENE % % % % Trona Crystalline Limestone % % % % For area to North see: Geology of the Magadi Area, KGS Report 42; Digital version by A. Guth % % % 36.5 °E % % % % 36.0 °E % % % % % High Magadi Beds (9-23.7 ka): yellow-brown silts over laminated clays with fish remains. Deposited % during % % Pl-gv % -2.0 ° -2.0 ° % % Gelai Xp % %% % a period of higher lake levels in both lakes Natron and Magadi. Coarser pebble beds seen near Len% derut Alluvial fan Undiff. Pelitic -

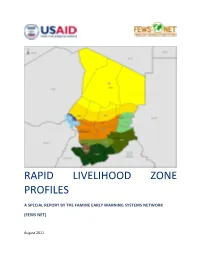

Rapid Livelihood Zone Profiles for Chad

RAPID LIVELIHOOD ZONE PROFILES A SPECIAL REPORT BY THE FAMINE EARLY WARNING SYSTEMS NETWORK (FEWS NET) August 2011 Contents Acknowledgments ......................................................................................................................................... 2 Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 3 The Uses of the Profiles ............................................................................................................................ 4 Key Concepts ............................................................................................................................................. 5 What is in a Livelihood Profile .................................................................................................................. 7 Methodology ............................................................................................................................................. 8 Rapid Livelihood Zone Profiles for Chad ....................................................................................................... 9 National Overview .................................................................................................................................... 9 Zone 1: South cereals and cash crops ..................................................................................................... 13 Zone 2: Southwest Rice Dominant .........................................................................................................