Professor Olanrewaju Folorunso

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg South Africa

University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg South Africa Fagunwa in Translation: Aesthetic and Ethics in the Translation of African Language Literature A research report submitted to the Faculty of Humanities, University of Witwatersrand Johannesburg, in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Masters of Arts. MODUPE ADEBAWO Johannesburg 2016 Co-supervised by Isabel Hofmeyr and Christopher Fotheringham 1 DECLARATION I declare that this research report is my own, unaided work. It is being submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts at the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg. It has not been submitted before for any other degree or examination at any other university. ________________________________________________________________________ Modupe Oluwayomi Adebawo. August 8, 2016. 2 ABSTRACT This study focuses on the aesthetics and ethics of translating African literature, using a case of two of D.O. Fagunwa’s Yoruba novels, namely; Igbo Olodumare (1949) translated by Wole Soyinka as In the Forest of Olodumare (2010) and Adiitu Olodumare (1961) translated by Olu Obafemi as The Mysteries of God (2012). More specifically, the overall aim of this study is to determine the positions of these target texts on the domestication and foreignization continuum. The study of these texts is carried out using a descriptive and systemic theoretical framework, based on Descriptive Translation Studies (DTS), Polysystem theory and the notion of norms of translational behaviour. The descriptive approach is extended by drawing on ideological and ethical approaches to translating postcolonial and marginalized literature. Lambert and Van Gorp’s model for the description of translation products is used in exploring the position of Fagunwa’s translated novels in the target literary system. -

The Impact of English Language Proficiency Testing on the Pronunciation Performance of Undergraduates in South-West, Nigeria

Vol. 15(9), pp. 530-535, September, 2020 DOI: 10.5897/ERR2020.4016 Article Number: 2D0D65464669 ISSN: 1990-3839 Copyright ©2020 Author(s) retain the copyright of this article Educational Research and Reviews http://www.academicjournals.org/ERR Full Length Research Paper The impact of English language proficiency testing on the pronunciation performance of undergraduates in South-West, Nigeria Oyinloye Comfort Adebola1*, Adeoye Ayodele1, Fatimayin Foluke2, Osikomaiya M. Olufunke2, and Fatola Olugbenga Lasisi3 1Department of Education, School of Education and Humanities, Babcock University, Ilishan-Remo, Ogun State, Nigeria. 2Department of Arts and Social Science, Education Department, Faculty of Education, National Open University of Nigeria, Abuja, Nigeria. 3Educational Management and Business Studies, Department of Education, Olabisi Onabanjo University, Ago Iwoye, Ogun State, Nigeria. Received 2 June, 2020; Accepted 8 August, 2020 This study investigated the impact of English Language proficiency testing on the pronunciation performance of undergraduates in South-west. Nigeria. The study was a descriptive survey research design. The target population size was 1243 (200-level) undergraduates drawn from eight tertiary institutions. The instruments used for data collection were the English Language Proficiency Test and Pronunciation Test. The English Language proficiency test was used to measure the performance of students in English Language and was adopted from the Post-UTME past questions from Babcock University Admissions Office on Post Unified Tertiary Admissions and Matriculation Examinations screening exercise (Post-UTME) for undergraduates in English and Linguistics. The test contains 20 objective English questions with optional answers. The instruments were validated through experts’ advice as the items in the instrument are considered appropriate in terms of subject content and instructional objectives while Cronbach alpha technique was used to estimate the reliability coefficient of the English Proficiency test, a value of 0.883 was obtained. -

Characterization of Staphylococcus Aureus Isolates Obtained from Health Care Institutions in Ekiti and Ondo States, South-Western Nigeria

African Journal of Microbiology Research Vol. 3(12) pp. 962-968 December, 2009 Available online http://www.academicjournals.org/ajmr ISSN 1996-0808 ©2009 Academic Journals Full Length Research Paper Characterization of Staphylococcus aureus isolates obtained from health care institutions in Ekiti and Ondo States, South-Western Nigeria Clement Olawale Esan1, Oladiran Famurewa1, 2, Johnson Lin3 and Adebayo Osagie Shittu3, 4* 1Department of Microbiology, University of Ado-Ekiti, P.M.B. 5363, Ado-Ekiti, Nigeria 2College of Science, Engineering and Technology, Osun State University, P.M.B. 4494, Osogbo, Nigeria 3School of Biochemistry, Genetics and Microbiology, University of KwaZulu-Natal (Westville Campus), Private Bag X54001, Durban, Republic of South Africa. 4Department of Microbiology, Obafemi Awolowo University, Ile-Ife, Nigeria Accepted 5 November, 2009 Staphylococcus aureus is one of the major causative agents of infection in all age groups following surgical wounds, skin abscesses, osteomyelitis and septicaemia. In Nigeria, it is one of the most important pathogen and a frequent micro-organism obtained from clinical samples in the microbiology laboratory. Data on clonal identities and diversity, surveillance and new approaches in the molecular epidemiology of this pathogen in Nigeria are limited. This study was conducted for a better understanding on the epidemiology of S. aureus and to enhance therapy and management of patients in Nigeria. A total of 54 S. aureus isolates identified by phenotypic methods and obtained from clinical samples and nasal samples of healthy medical personnel in Ondo and Ekiti States, South-Western Nigeria were analysed. Typing was based on antibiotic susceptibility pattern (antibiotyping), polymerase chain reaction-restriction fragment length polymorphisms (PCR-RFLPs) of the coagulase gene and pulsed field gel electrophoresis (PFGE). -

Hospital Cash Approved Providers List

HOSPITAL CASH APPROVED PROVIDERS LIST S/N PROVIDER NAME ADDRESS REGION STATE 1 Life care clinics Ltd 8, Ezinkwu Street Aba, Aba Abia 2 New Era Hospital 213/215 Azikiwe Road, Aba Aba Abia 3 J-Medicare Hospital 73, Bonny Street, Umuahia By Enugu Road Umuahia Abia 4 New Era Hospital 90B Orji River Road, Umuahia Umuahia Abia 10,Mobolaji Johnson street,Apo Quarters,Zone Abuja Abuja 5 Rouz Hospital & Maternity D,2nd Gate,Gudu District 6 Sisters of Nativity Hospital Phase 1, Jikwoyi, abuja municipal Area Council Abuja Abuja 7 Royal Lords Hospital, Clinics & Maternity Ltd Plot 107, Zone 4, Dutse Alhaji, Abuja Dutse Alhaji Abuja 8 Adonai Hospital 3, Adonai Close, Mararaba, Garki Garki Abuja Plot 202, Bacita Close, Off Plateau Street, Area 2 , Garki Abuja 9 Dara Clinics Garki FHA Lugbe FHA Estate, Lugbe, Abuja Lugbe Abuja 10 PAAFAG Hospital & Medical Diagnosis Centre 11 Central Hospital, Masaka Masaka Masaka Abuja 12 Pan Raf Hospital Limited Nyanya Phase 4 Nyanya Abuja Ahoada Close, By Nta Headquarters, Besides Uba, Abuja Abuja 13 Kinetic Hospital Area 11 14 Lona City Care Hospital 48, Transport Abuja Abuja Plot 145, Kutunku, Near Radio House, Gwagwalada Abuja 15 Jerab Hospital Gwagwalada 16 Paakag Hospital & Medical Diagnosis Centre Fha Lugbe, Fha Estate, Lugbe, Abuja Lugbe Abuja 17 May Day Hospital 1, Mayday Hospital Street, Mararaba, Abuja Mararaba Abuja 18 Suzan Memorial Hospital Uphill Suleja, Near Suleja Club, Gra, Suleja Suleja Abuja 64, Moses Majekodunmi Crescent,Utako, Abuja Utako Abuja 19 Life Point Medical Centre 7, Sirasso Close, Off Sirasso Crescent, Zone 7, Wuse Abuja 20 Health Gate Hospital Wuse. -

Integrative Theories of Medicine: a (W)Holistic Vision

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Master's Theses Theses and Dissertations 1994 Integrative Theories of Medicine: A (W)Holistic Vision Kathryn B. Forestal Loyola University Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_theses Part of the Integrative Medicine Commons Recommended Citation Forestal, Kathryn B., "Integrative Theories of Medicine: A (W)Holistic Vision" (1994). Master's Theses. 3974. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_theses/3974 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 1994 Kathryn B. Forestal LOYOLA UNIVERSITY CHICAGO INTEGRATIVE THEORIES OF MEDICINE: A (W)HOLISTIC VISION A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS DEPARTMENT OF GRADUATE LIBERAL STUDIES BY KATHRYN B. FORESTAL CHICAGO, ILLINOIS MAY 1994 Copyright by Kathryn B. Foresta!, 1994 All rights reserved. ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to express my gratitude to the members of my thesis committee: Dr. Cheryl Johnson Odim, Director, Dr. Ayana Karanja, and Dr. Paolo Giordano, Dept. Chairperson of Graduate Liberal Studies. This study could not have been completed without the assistance and research material of Dr. Norman R. Farnsworth,Director and Research Professor, Program for Collaborative Research in the Pharmaceutical Sciences, College of Pharmacy, University of Illinois at Chicago and his assistant, Mary Lou Quinn. -

Odo/Ota Local Government Secretariat, Sango - Agric

S/NO PLACEMENT DEPARTMENT ADO - ODO/OTA LOCAL GOVERNMENT SECRETARIAT, SANGO - AGRIC. & BIO. ENGINEERING 1 OTA, OGUN STATE AGEGE LOCAL GOVERNMENT, BALOGUN STREET, MATERNITY, AGRIC. & BIO. ENGINEERING 2 SANGO, AGEGE, LAGOS STATE AHMAD AL-IMAM NIG. LTD., NO 27, ZULU GAMBARI RD., ILORIN AGRIC. & BIO. ENGINEERING 3 4 AKTEM TECHNOLOGY, ILORIN, KWARA STATE AGRIC. & BIO. ENGINEERING 5 ALLAMIT NIG. LTD., IBADAN, OYO STATE AGRIC. & BIO. ENGINEERING 6 AMOULA VENTURES LTD., IKEJA, LAGOS STATE AGRIC. & BIO. ENGINEERING CALVERTON HELICOPTERS, 2, PRINCE KAYODE, AKINGBADE MECHANICAL ENGINEERING 7 CLOSE, VICTORIA ISLAND, LAGOS STATE CHI-FARM LTD., KM 20, IBADAN/LAGOS EXPRESSWAY, AJANLA, AGRIC. & BIO. ENGINEERING 8 IBADAN, OYO STATE CHINA CIVIL ENGINEERING CONSTRUCTION CORPORATION (CCECC), KM 3, ABEOKUTA/LAGOS EXPRESSWAY, OLOMO - ORE, AGRIC. & BIO. ENGINEERING 9 OGUN STATE COCOA RESEARCH INSTITUTE OF NIGERIA (CRIN), KM 14, IJEBU AGRIC. & BIO. ENGINEERING 10 ODE ROAD, IDI - AYANRE, IBADAN, OYO STATE COKER AGUDA LOCAL COUNCIL, 19/29, THOMAS ANIMASAUN AGRIC. & BIO. ENGINEERING 11 STREET, AGUDA, SURULERE, LAGOS STATE CYBERSPACE NETWORK LTD.,33 SAKA TIINUBU STREET. AGRIC. & BIO. ENGINEERING 12 VICTORIA ISLAND, LAGOS STATE DE KOOLAR NIGERIA LTD.,PLOT 14, HAKEEM BALOGUN STREET, AGRIC. & BIO. ENGINEERING OPP. TECHNICAL COLLEGE, AGIDINGBI, IKEJA, LAGOS STATE 13 DEPARTMENT OF PETROLEUM RESOURCES, 11, NUPE ROAD, OFF AGRIC. & BIO. ENGINEERING 14 AHMAN PATEGI ROAD, G.R.A, ILORIN, KWARA STATE DOLIGERIA BIOSYSTEMS NIGERIA LTD, 1, AFFAN COMPLEX, 1, AGRIC. & BIO. ENGINEERING 15 OLD JEBBA ROAD, ILORIN, KWARA STATE Page 1 SIWES PLACEMENT COMPANIES & ADDRESSES.xlsx S/NO PLACEMENT DEPARTMENT ESFOOS STEEL CONSTRUCTION COMPANY, OPP. SDP, OLD IFE AGRIC. & BIO. ENGINEERING 16 ROAD, AKINFENWA, EGBEDA, IBADAN, OYO STATE 17 FABIS FARMS NIGERIA LTD., ILORIN, KWARA STATE AGRIC. -

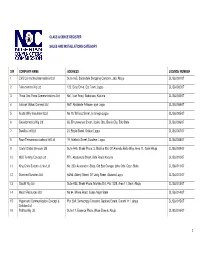

S/N COMPANY NAME ADDRESS LICENSE NUMBER 1 CVS Contracting International Ltd Suite 16B, Sabondale Shopping Complex, Jabi, Abuja CL/S&I/001/07

CLASS LICENCE REGISTER SALES AND INSTALLATIONS CATEGORY S/N COMPANY NAME ADDRESS LICENSE NUMBER 1 CVS Contracting International Ltd Suite 16B, Sabondale Shopping Complex, Jabi, Abuja CL/S&I/001/07 2 Telesciences Nig Ltd 123, Olojo Drive, Ojo Town, Lagos CL/S&I/002/07 3 Three One Three Communications Ltd No1, Isah Road, Badarawa, Kaduna CL/S&I/003/07 4 Latshak Global Concept Ltd No7, Abolakale Arikawe, ajah Lagos CL/S&I/004/07 5 Austin Willy Investment Ltd No 10, Willisco Street, Iju Ishaga Lagos CL/S&I/005/07 6 Geoinformatics Nig Ltd 65, Erhumwunse Street, Uzebu Qtrs, Benin City, Edo State CL/S&I/006/07 7 Dwellins Intl Ltd 21, Boyle Street, Onikan Lagos CL/S&I/007/07 8 Race Telecommunications Intl Ltd 19, Adebola Street, Surulere, Lagos CL/S&I/008/07 9 Clarfel Global Services Ltd Suite A45, Shakir Plaza, 3, Michika Strt, Off Ahmadu Bello Way, Area 11, Garki Abuja CL/S&I/009/07 10 MLD Temmy Concept Ltd FF1, Abeoukuta Street, Bida Road, Kaduna CL/S&I/010/07 11 King Chris Success Links Ltd No, 230, Association Shop, Old Epe Garage, Ijebu Ode, Ogun State CL/S&I/011/07 12 Diamond Sundries Ltd 54/56, Adeniji Street, Off Unity Street, Alakuko Lagos CL/S&I/012/07 13 Olucliff Nig Ltd Suite A33, Shakir Plaza, Michika Strt, Plot 1029, Area 11, Garki Abuja CL/S&I/013/07 14 Mecof Resources Ltd No 94, Minna Road, Suleja Niger State CL/S&I/014/07 15 Hypersand Communication Concept & Plot 29A, Democracy Crescent, Gaduwa Estate, Durumi 111, abuja CL/S&I/015/07 Solution Ltd 16 Patittas Nig Ltd Suite 17, Essence Plaza, Wuse Zone 6, Abuja CL/S&I/016/07 1 17 T.J. -

African Traditional Religions in Mainstream Religious Studies

AFRICAN TRADITIONAL RELIGIONS IN MAINSTREAM RELIGIOUS STUDIES DISCOURSE: THE CASE FOR INCLUSION THROUGH THE LENS OF YORUBA DIVINE CONCEPTUALIZATIONS Vanessa Turyatunga Thesis submitted to the University of Ottawa in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Master of Arts in Religious Studies Department of Classics and Religious Studies Faculty of Arts University of Ottawa © Vanessa Turyatunga, Ottawa, Canada, 2019 Abstract The history of African Traditional Religions (ATRs), both inside and outside academia, is one dominated by exclusions. These exclusions were created by the colonial framing of ATRs as primitive, irrational and inferior to other religions. This colonial legacy is in danger of being preserved by the absence of ATRs from the academic study of religion, legal definitions of religion, and global and local conversations about religion. This thesis will explore the ways that a more considered and accurate examination of the understudied religious dimensions within ATRs can potentially dismantle this legacy. It will do so by demonstrating what this considered examination might look like, through an examination of Yoruba divine conceptualizations and the insights they bring to our understanding of three concepts in Religious Studies discourse: Worship, Gender, and Syncretism. This thesis will demonstrate how these concepts have the ability to challenge and contribute to a richer understanding of various concepts and debates in Religious Studies discourse. Finally, it will consider the implications beyond academia, with a focus on the self-understanding of ATR practitioners and African communities. It frames these implications under the lens of the colonial legacy of ‘monstrosity’, which relates to their perception as primitive and irrational, and concludes that a more considered examination of ATRs within the Religious Studies framework has the potential to dismantle this legacy. -

Socio-Economic Impacts of Settlers in Ado-Ekiti

International Journal of History and Cultural Studies (IJHCS) Volume 3, Issue 2, 2017, PP 19-26 ISSN 2454-7646 (Print) & ISSN 2454-7654 (Online) DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.20431/2454-7654.0302002 www.arcjournals.org Socio-Economic Impacts of Settlers in Ado-Ekiti Adeyinka Theresa Ajayi (PhD)1, Oyewale, Peter Oluwaseun2 Department of History and International Studies, Ekiti State University, Ado-Ekiti, Ekiti State Nigeria Abstract: Migration and trade are two important factors that led to the commercial growth and development of Ado-Ekiti during pre-colonial, colonial and post colonial period. These twin processes were facilitated by efforts of other ethnic groups, most notably the Ebira among others, and other Yoruba groups. Sadly there is a paucity of detailed historical studies on the settlement pattern of settlers in Ado-Ekiti. It is in a bid to fill this gap that this paper analyses the settlement pattern of settlers in Ado-Ekiti. The paper also highlights the socio- economic and political activities of settlers, especially their contributions to the development of Ado-Ekiti. Data for this study were collected via oral interviews and written sources. The study highlights the contributions of settlers in Ado-Ekiti to the overall development of the host community 1. INTRODUCTION Ado-Ekiti, the capital of Ekiti state is one of the state in southwest Nigeria. the state was carved out from Ondo state in 1996, since then, the state has witness a tremendous changes in her economic advancement. The state has witness the infix of people from different places. Settlement patterns in intergroup relations are assuming an important area of study in Nigeria historiography. -

Impact of the Media on the Senior Secondary School Students

Academic Leadership: The Online Journal Volume 8 Article 32 Issue 4 Fall 2010 1-1-2010 Impact Of The ediM a On The eS nior Secondary School Students Performance In Speech Work In English Language G.O. Oyinloye I.O. Adeleye Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.fhsu.edu/alj Part of the Educational Leadership Commons, Higher Education Commons, and the Teacher Education and Professional Development Commons Recommended Citation Oyinloye, G.O. and Adeleye, I.O. (2010) "Impact Of The eM dia On The eS nior Secondary School Students Performance In Speech Work In English Language," Academic Leadership: The Online Journal: Vol. 8 : Iss. 4 , Article 32. Available at: https://scholars.fhsu.edu/alj/vol8/iss4/32 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by FHSU Scholars Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Academic Leadership: The Online Journal by an authorized editor of FHSU Scholars Repository. academicleadership.org http://www.academicleadership.org/857/impact-of-the-media-on-the-senior- secondary-school-students-performance-in-speech-work-in-english-language/ Academic Leadership Journal Introduction. Most Nigerian students learn English Language as a second Language (L2).They have acquired their mother tongues (L1) and are very proficient in them before entering the school. In most cases, many secondary school students do not have the opportunity to use English language at home. For such students, English Language learning and use is restricted to the classroom. Therefore, these students use their mother tongue more in the school environment, at home and for interpersonal relationships. These practices are negatively affecting the production of some sounds in English Language, which is the language of education, government, commerce and international communication. -

APPRECIATING the U.Iel of LITERATURE: a YORUBA EXAMPLE

- APPRECIATING THE U.IEl OF LITERATURE: A YORUBA EXAMPLE .,~ , ' - " .'~ \0 ;. , I..• .. ,l..A/f ..··,",.:.' ':"}..... • BY ISAAC OLUGBOYEGA ALABA UNIVERSITY OF LAGOS Pl{ESS - 2002 INAUGURAL LECTURE SERIES APPRECIATING THE UJU OF LITERATURE: A YORUBA EXAMPLE An Inaugural Lecture Delivered at the University of Lagos on Wednesday, 22nd May, 2002. i '; BY ISAAC OLUGBOYEGA ALABA B.A. (Hons.) (Lagos); M.A. (Ibadan) Ph.D. (Lagos) Professor of Yoruba Department of African and Asian Studies University of Lagos University of Lagos, 2002 ©I. O. ALABA All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of the author. First Published 2002 By University of Lagos Press Unilag P.O. Box 132, University of Lagos, Akoka, Yaba - Lagos Nigeria ISSN 1119 - 4456 APPRECIATING THE USES OF LITERA TUR . A YORUBA EXAMPLE Acknowledgements Mr. Vice-Chancellor Sir, Distinguished Principal Officers of the University of Lagos, Fellow Colleagues, Invited Guests, Beloved Students, Ladies and Gentlemen, Good evening. Glory be to the God of my heart, the God of my realization for the gifts of Light, Life and Love. Many thanks to: my living-dead parents (Chief Gabriel Ojewale Alaba alias Owayanrinwayanrin kowosi QmQ Subuola and Ruth Eegunbiyii QmQ Afolabi Onibudo); my numerous teachers notably Elder Ogunjobi Aylnde, Elder Qla Olasunsi, Senator Professor Afolabi Olabimtan, Ijoye Emeritus Professor Adeboye -

Stylistic Embedding in Yoruba Literature

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 391 370 FL 023 524 AUTHOR Olabode, Afolabi TITLE Stylistic Embedding in Yoruba Literature. PUB DATE Mar 95 NOTE 21p.; Paper presented at the Annual Conference on African Linguistics (26th, Los Angeles, CA, March 24-26, 1995). PUB TYPE Reports Evaluative/Feasibility (142) Speeches/Conference Papers (150) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC01 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS African Languages; Discourse Analysis; Fiction; Foreign Countries; *Language Patterns; Language Research; Linguistic Theory; *Literature; Literature Appreciation; Novels; Poetry; *Sentence Structure; Transformational Generative Grammar; Uncommonly Taught Languages; *Yoruba ABSTRACT The process of embedding, a term used in generative grammar to refer to a construction in which a sentence is included within another sentence, is examined as it occurs in Yoruba literature. Examples are drawn from Yoruba praise poetry, in both written and oral form and within Yoruba novels. Forms of embedding identified include those to draw attention to the subject of a poem, to digress from the main topic and provide brief relief from it, bring humor into a tense circumstance, and make direct or indirect comment on the situation or character. Two additional forms of embedding are noted: the embedding of minor stories within the main story, sometimes using incantation or proverb, and that of poetry. Implications of the analysis for creative writing and for evaluation of an author's work and style are discussed briefly. (MSE) ***********************************************************************