Prince Kamal Eldin Hussein

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Saad Zaghloul Pro- Or Anti-Concession Extension of the Suez Canal 1909-1910 Rania Ali Maher

IAJFTH Volume 3, No.3, 2017 ـــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــ Saad Zaghloul Pro- or Anti-Concession Extension of the Suez Canal 1909-1910 Rania Ali Maher Abstract The years 1909-1910 witnessed one of the most critical chapters in the history of the Suez Canal. The attempt of the British occupation to obtain ratification from the Egyptian General Assembly for extending the concession of the Suez Canal Company to 2008 made a great stir among the Egyptians and provoked new furies of national agitation against the British. Although there was a unanimous condemnation for the proposal, Saad Zaghloul played a different role in dealing with the problem. He staunchly defended the project in the Assembly that he had originally rejected, an act that caused many to accuse him of being complicit with the British. Despite the fact that the vehement opposition to the project led the Assembly to turn it down, Zaghloul’s assessment of the situation raised a lot of questions concerning his involvement with the occupation and his relations with the Nationalists during this period. In light of the General Assembly Meetings, this paper is an endeavor to reveal the ambivalent role played by Zaghloul in this issue. Keywords Saad Zaghloul - Suez Canal Concession - General Assembly - Eldon Gorst. Introduction Since the time of the Denshway incident of 1906, Nationalist agitation against the British Occupation had increased steadily. By the second half of 1909 and the beginning of 1910, this anti-British sentiment came to a head with the attempts of Eldon Gorst, the British Consul-General (1907-1911) and of Butrus Pasha Ghali, the Prime Minister (1908-1910), to get an approval from the General Assembly for extending the Suez Canal concession for another forty years. -

Parliament Special Edition

October 2016 22nd Issue Special Edition Our Continent Africa is a periodical on the current 150 Years of Egypt’s Parliament political, economic, and cultural developments in Africa issued by In this issue ................................................... 1 Foreign Information Sector, State Information Service. Editorial by H. E. Ambassador Salah A. Elsadek, Chair- man of State Information Service .................... 2-3 Chairman Salah A. Elsadek Constitutional and Parliamentary Life in Egypt By Mohamed Anwar and Sherine Maher Editor-in-Chief Abd El-Moaty Abouzed History of Egyptian Constitutions .................. 4 Parliamentary Speakers since Inception till Deputy Editor-in-Chief Fatima El-Zahraa Mohamed Ali Current .......................................................... 11 Speaker of the House of Representatives Managing Editor Mohamed Ghreeb (Documentary Profile) ................................... 15 Pan-African Parliament By Mohamed Anwar Deputy Managing Editor Mohamed Anwar and Shaima Atwa Pan-African Parliament (PAP) Supporting As- Translation & Editing Nashwa Abdel Hamid pirations and Ambitions of African Nations 18 Layout Profile of Former Presidents of Pan-African Gamal Mahmoud Ali Parliament ...................................................... 27 Current PAP President Roger Nkodo Dang, a We make every effort to keep our Closer Look .................................................... 31 pages current and informative. Please let us know of any Women in Egyptian and African Parliaments, comments and suggestions you an endless march of accomplishments .......... 32 have for improving our magazine. [email protected] Editorial This special issue of “Our Continent Africa” Magazine coincides with Egypt’s celebrations marking the inception of parliamentary life 150 years ago (1688-2016) including numerous func- tions atop of which come the convening of ses- sions of both the Pan-African Parliament and the Arab Parliament in the infamous city of Sharm el-Sheikh. -

Annales Islamologiques

MINISTÈRE DE L'ÉDUCATION NATIONALE, DE L'ENSEIGNEMENT SUPÉRIEUR ET DE LA RECHERCHE ANNALES ISLAMOLOGIQUES en ligne en ligne en ligne en ligne en ligne en ligne en ligne en ligne en ligne en ligne AnIsl 50 (2016), p. 107-143 Mohamed Elshahed Egypt Here and There. The Architectures and Images of National Exhibitions and Pavilions, 1926–1964 Conditions d’utilisation L’utilisation du contenu de ce site est limitée à un usage personnel et non commercial. Toute autre utilisation du site et de son contenu est soumise à une autorisation préalable de l’éditeur (contact AT ifao.egnet.net). Le copyright est conservé par l’éditeur (Ifao). Conditions of Use You may use content in this website only for your personal, noncommercial use. Any further use of this website and its content is forbidden, unless you have obtained prior permission from the publisher (contact AT ifao.egnet.net). The copyright is retained by the publisher (Ifao). Dernières publications 9782724708288 BIFAO 121 9782724708424 Bulletin archéologique des Écoles françaises à l'étranger (BAEFE) 9782724707878 Questionner le sphinx Philippe Collombert (éd.), Laurent Coulon (éd.), Ivan Guermeur (éd.), Christophe Thiers (éd.) 9782724708295 Bulletin de liaison de la céramique égyptienne 30 Sylvie Marchand (éd.) 9782724708356 Dendara. La Porte d'Horus Sylvie Cauville 9782724707953 Dendara. La Porte d’Horus Sylvie Cauville 9782724708394 Dendara. La Porte d'Hathor Sylvie Cauville 9782724708011 MIDEO 36 Emmanuel Pisani (éd.), Dennis Halft (éd.) © Institut français d’archéologie orientale - Le Caire Powered by TCPDF (www.tcpdf.org) 1 / 1 MohaMed elshahed* Egypt Here and There The Architectures and Images of National Exhibitions and Pavilions, 1926–1964 • abstract In 1898 the first agricultural exhibition was held on the island of Gezira in a location accessed from Cairo’s burgeoning modern city center via the Qasr el-Nil Bridge. -

Bingöl Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü Dergisi Yıl: 4/ Cilt: 4 /Sayı:8/ Güz 2014

Bingöl Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü Dergisi Yıl: 4/ Cilt: 4 /Sayı:8/ Güz 2014 HISTORICAL ALLEGORIES IN NAGUIB MAHFOUZ’S CAIRO TRILOGY Naguib M ahfouz’un Kahire Üçlemesi Adli Eserindeki Tarihsel Alegoriler Özlem AYDIN* Abstract The purpose o f this work is to analyze the “Cairo Trilogy” o f a Nobel Prize winner for literature, the Egyptian writer Naguib Mahfouz with the method o f new historicism. In “Cairo Trilogy”, Mahfouz presents the striking events oflate history of Egypt by weaving them with fıction. As history is one o f the most useful sources of literature the dense relationship between history and literature is beyond argument. When viewed from this aspect, a new historicist approach to literature will provide a widened perspective to both literature and history by enabling different possibilities for crucial reading. It is expected that the new historicist analysis o f “Cairo Trilogy” will enable a better insight into the literature and historical background o f Egypt. Key Words: Naguib Mahfouz, Cairo Trilogy, History, Egypt, New Historicism Özet Bu çalışmanın amacı Mısır ’lı Nobel ödüllü yazar Naguib Mahfouz ’un “Kahire Üçlemesi”adlı eserini yeni tarihselcilik metodunu kullanarak analiz etmektir. “Kahire Üçlemesi”nde Mahfouz, Mısır’ın yakın tarihindeki çarpıcı olayları kurgu ile harmanlayarak sunmuştur. Tarih, edebiyatın en faydalı kaynaklarından biri olduğundan, tarih ve edebiyat arasındaki sıkı ilişki tartışılmazdır. Bu açıdan bakıldığında, edebiyata yeni tarihselci bir yaklaşım çapraz okuma konusunda farklı imkanlar sunarak hem edebiyata hem tarihe daha geniş bir bakış açısı sağlayacaktır. “Kahire Üçlemesi”nin yeni tarihselci analizinin Mısır’ın edebiyatının ve tarihsel arkaplanının daha iyi kavranmasını sağlaması beklenmektedir. -

The Emergence of Egyptian Radio 12 3

1 2018 Issue Edited by Grammargal 2 The Voice of the Arabs The Radio Station That Brought Down Colonialism Abbas Metwalli 3 Contents 1. Introduction, by Ahmed Said 6 2. The Emergence of Egyptian Radio 12 3. The Founding of the Voice of the Arabs 18 4. Mohamed Fathi Al-Deeb 27 5. The Voice of the Arabs during Nasser’s Era 34 6. The Influence of the Arab parameter 37 7. The Call for Arab Nationalism 58 8. Arabic Broadcasts from Cairo 62 9. The June 1967 War 66 10. A Commentary by Ahmed Said 68 11. The Maligned Ahmed Said 73 12. Ahmed Said, by Sayed Al-Ghadhban 76 13. The 60th Anniversary, by Fahmy Omar 79 14. The Voice in the Eyes of Foreigners 81 15. Whose Voice 85 16. Nasser’s Rule & The role of Radio 91 17. Nasser’s Other Voice, by William S. Ellis 93 18. The Voice of the Arabs during Sadat’s Era 97 19. The Broadcasters’ Massacre of 1971 99 20. Mohamed Orouq 112 21. May 15,1971 in the Memory of Egyptians 117 22. The Voice of the Arabs, a school of Innovators 118 23. The Voice of the Arabs During Mubarak’s Era 140 24. The Voice During the Muslim Brotherhood Era 145 25. The Voice of the Arabs Female Stars 156 26. The Age of Radio Networks 161 27. The Voice of the Arabs Network 163 28. The Radio Syle of the Voice of the Arabs 166 29. Chiefs of the Voice of the Arabs 172 30. The Voice of the Arabs today 186 31. -

No Longer Dhimmis: How European Intervention in the Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Centuries Empowered Copts in Egypt

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons CUREJ - College Undergraduate Research Electronic Journal College of Arts and Sciences 2012 No Longer Dhimmis: How European Intervention in the Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Centuries Empowered Copts in Egypt Patrick Victor Elyas University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/curej Part of the Islamic World and Near East History Commons, Missions and World Christianity Commons, and the Near Eastern Languages and Societies Commons Recommended Citation Elyas, Patrick Victor, "No Longer Dhimmis: How European Intervention in the Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Centuries Empowered Copts in Egypt" 01 January 2012. CUREJ: College Undergraduate Research Electronic Journal, University of Pennsylvania, https://repository.upenn.edu/curej/156. This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/curej/156 For more information, please contact [email protected]. No Longer Dhimmis: How European Intervention in the Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Centuries Empowered Copts in Egypt Abstract This paper will examine how European intervention in Egypt from Napoleon's occupation in 1798 to the departure of the monarchy in 1952 changed the social landscape of the country. Through Napoleonic decrees, diplomatic pressure, influence on the Mohammad Ali dynasty, and the expansion of European missionary education in Egypt, European involvement in Egyptian affairs was essential in allowing Copts and other Christians to reverse centuries -

1 India-Egypt Relations India and Egypt, Two of the World's Oldest Civilizations, Have Enjoyed a History of Close Contact From

India-Egypt Relations India and Egypt, two of the world’s oldest civilizations, have enjoyed a history of close contact from ancient times. Even prior to the Common Era, Ashoka’s edicts refer to his relations with Egypt under Ptolemy II. In modern times, Mahatma Gandhi and Saad Zaghloul shared common goals on the independence of their countries, a relationship that was to blossom into an exceptionally close friendship between Gamal Abdel Nasser and Jawaharlal Nehru, leading to a Friendship Treaty between the two countries in 1955. The Non-Aligned Movement, led by Nehru and Nasser, was a natural concomitant of this relationship. High Level Visits 2. Since the 1980s, there have been four Prime Ministerial visits from India to Egypt: Shri Rajiv Gandhi (1985); Shri P. V. Narasimha Rao (1995); Shri I. K. Gujral (1997); and Dr Manmohan Singh (2009). Prime Minister Dr Manmohan Singh participated in the XV NAM Summit held in Sharm EI-Sheikh in July 2009. 3. From the Egyptian side, the President visited India in 1982, in 1983 (NAM Summit) and again in November 2008, during which a number of agreements on cooperation in health, medicine, outer space, and trade were signed. High level exchanges with Egypt have continued after the 2011 Egyptian Revolution and the Egyptian Government under President Mohamed Morsy has shown a keen interest in maintaining the scale and scope of the bilateral relationship; since January 2011, nine Ministerial visits between India and Egypt have taken place, including the visit of the External Affairs Minister (EAM) of India to Cairo in March 2012. -

MUNUC XXIX Cabinet of Egypt Background Guide

THE CABINET OF EGYPT, 1954 MUNUC XXIX Cabinet Briefing LETTER FROM THE CHAIR Greetings Delegates! Welcome to the first cabinet meeting of our new government. In addition to preparing to usher in a new age of prosperity in Egypt, I am a fourth year at the University of Chicago, alternatively known as Hannah Brodheim. Originally from New York City, I am studying economics and computer science. I am also a USG for our college conference, ChoMUN. I have previously competed with the UChicago competitive Model UN team. I also help run Splash! Chicago, a group which organizes events where UChicago students teach their absurd passions to interested high school students. Egypt has not had an easy run of it lately. Outdated governance systems, and the lack of investment in the country under the British has left Egypt economically and politically in the dust. Finally, a new age is dawning, one where more youthful and more optimistic leadership has taken power. Your goals are not short term, and you do not intend to let Egypt evolve slowly. Each of you has your personal agenda and grudges; what solution is reached by the committee to each challenge ahead will determine the trajectory of Egypt for years to come. We will begin in 1954, before the cabinet has done anything but be formed. The following background guide is to help direct your research; do not limit yourself to the information contained within. Success in committee will require an understanding of the challenges Nasser’s Cabinet faces, and how the committee and your own resources may be harnessed to overcome them. -

Quality Standard Application Record

FONASBA QUALITY STANDARD APPROVALS GRANTED FONASBA MEMBER ASSOCIATION: ALEXANDRIA CHAMBER OF SHIPPING DATE NO.. COMPANY HEAD OFFICE AWARDED ADDRESS 1 ADDRESS 2 ADDRESS 3 ADDRESS 4 ADDRESS 5 ADDRESS 6 CONTACT PERSON TELEPHONE E-MAIL BRANCH OFFICES web site .+203 4840680 KADMAR SHIPPING COM. Alexandria :32 Saad Zaghloul Str., Alexandria, Egypt 15/01/2018 cairo:15 Lebanon St,Mohandseen Damietta:west of Damietta Port Said:Mahrousa Bulding,Mahmoud Suez :28 Agohar ElKaid St., , Port Tawfik.Safaga:Bulding of ElSalam Co. for Admiral Hatim Elkady +022 334445734 port,areaNo.7, BlockNo.6 infrort of Sedky and Panma St. maritime 4th floor,flat No.12,in front Chairman [email protected] +02 05 7222230-31 [email protected] security forces. of safagaa port-Read Sea Eng .Medhat EL Kady Cairo, Cairo Air Port, Giza, Port +02 066334401816 [email protected] 1 Vice Chairman Said, Damietta, Suez, El Arish www.kadmar.com +02 0623198345 [email protected] and Safaga +02 065 3256635 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] EGYMAR SHIPPING &LOGISTICS COM. Alexandria : 45 El Sultan Hussein St from Victor Bassily – 15/01/2018 Cairo :5 B Asmaa Fahmy division , Ard ElGulf , Damietta : 231 Invest build next to Port Said : Foribor Building , Manfis and Suez : 7 ElMona St , Door 5 , Flat 6 , Waleed Badr Khartoum Square Above Audi Bank - 2nd and 3rd floor Masr Elgedida , Cairo khalij , 2 nd floor Nahda St , 3 rd floor , office 311 Port Tawfik. Chairman .+203 4782440/441/442 +02 02 24178435 +02 05 72291226 Cairo, Port Said, Damietta, 2 [email protected] -

Recent .. Constitutional Develop~1Ents in Egypt

RECENT .. CONSTITUTIONAL DEVELOP~1ENTS IN EGYPT . By tht Latt SIR \VILLIAM HAYTER, K.B.E. LATI! LEGAL ADVISE II. TO THI! EGYPTIAN GOVUNMI!NT SECOND IMPRESSION C . f . ~ i '11 'Jll 'D G E 'liE I'NIVERSIT\' PRESS I 9 Z 5 RECENT CONSTITUTIONAL DEVELOP¥ENTS IN EGYPT CAMBRIDGE UNlVBRSlTY PRESS LONDON: Fetter Lane NewYoaK The Macmlllan Co. BoMBAY, CALCUTtA and MADRAS Macmillan lind Co., Ltd • . TOI\ONTO The Macmillan Co. of Canada, Ltd. ToKYO Maruzen·I<abushlkl·Kaitha · All rlshta reaervcd RECENT CONSTITUTIONAL I DEVELOPMENTS IN EGYPT By the Late SxR WILLIAM HAYTER, K.B.E. LATI LI!CAL ADVISI!R. TO THI EGYPTIAN COVBilNMINT SECOND IMPRESSION C.ltM'Bt.l{IVGE AT THE UNIVERSITY PRESS 192 s First Impression 1924 Second Impression 1925 l'lUNTED IN ORI!AT BRITAIN HE two lectures here printed were prepared by Sir William Hayter for the Local Lectures Summer TMeeting at Cambridge in 1924. Illness prevented his travelling and the first lecture was read to a large audience on Saturday, August 2. It was so able and impressive that the author was asked to allow both lectures to be published. Before the answer could come the sad news of his death on August 5 was announced, but Lady Hayter at once gave the required permission. The second lecture was read on August 7, some hundreds of students again being present from many countries including Egypt. The importance of such a pronounce ment is obvious, coming as it does from one who had held high .office for so long. No one can read it without regret that such a sane, impartial, and sympathetic states man is no longer at hand to help in the solution of the difficult problems in Egypt which still have to be faced. -

Egypt's Difficult Transition

1 Egypt’s Difficult Transition: Options for the International Community HAFEZ GhANEM Change is under way in Egypt. But, its end is not clear and the road ahead is likely to be long and difficult. —Bruce K. Rutherford, Princeton University On June 30, 2013, millions of Egyptians took to the streets demand- ing that their first democratically elected president, Mohamed Morsi, of the Muslim Brotherhood, step down and calling for new elections. Three days later, on July 3, the minister of defense—surrounded by the country’s leading secular politicians, Salafist leaders, and the heads of Al-Azhar (the highest Islamic authority in Egypt) and of the Coptic Orthodox Christian Church—announced the president’s ouster. The announcement sparked notably different responses around the country. Tahrir Square was filled with cheering crowds happy to be rid of what they considered to be an Islamist dictatorship. In other parts of Cairo, Nasr City and Ennahda Square, Brotherhood supporters started sit-ins to call for the return of the man they deemed their legitimate president. On August 14, 2013, security forces moved to break up the Brother- hood sit-ins. Hundreds were killed. Armed clashes occurred all across the country, with more victims. Coptic churches, Christian schools, police stations, and government offices were attacked, apparently by 1 Ghanem_Arab Spring V2_i-xvi_1-444_final.indd 1 11/20/15 2:47 PM 2 HAFEZ GHANEM angry Brotherhood sympathizers.1 At the same time, other citizens, exasperated by the Brotherhood, joined the security forces in attacking them. The new interim government closed Islamist television stations and jailed Brotherhood leaders. -

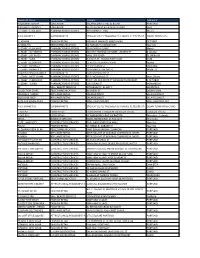

Merchant Name Business Type Address Address 2 NAZEEM

Merchant Name Business Type Address Address 2 NAZEEM BUTCHERY EDUCATION SALAH ELDIN ST AND EL BAZAR PORTSAID BRILLIANCE SCHOOLS EDUCATION KILLO 26 CAIRO ALEX DESERT ROAD GIZA EL EZABY - ELSALAM E PHARMACY/DRUG STORES 516 KORNISH ELNILE Maadi ALFA MARKET 1 SUPERMARKETS ETISALAT CO. EL TAGAMOA EL KHAMES -ELTESEEN ST DOWN TOWN BLD., EL ADHAM FASHION RETAIL MEHWAR MARKAZY ABAZIA MALL OCTOBER ELHANA TEL TELECOMMUNICATION 12 HASSAN EL MAMOUN ST. Nasr city EL EZABY - ELSALAM E PHARMACY/DRUG STORES 516 KORNISH ELNILE Maadi EL EZABY - OCTOBER U PHARMACY/DRUG STORES 283 HAY 7 BEHIND OCTOBER UNIVERCITY 6 October EL EZABY - SKY PLAZA PHARMACY/DRUG STORES MALL SKY PLAZA EL SHEROUK EL EZABY - SUEZ PHARMACY/DRUG STORES ELGALAA ST, ASWAN INSTITUION SUEZ EL EZABY - ELDARAISA PHARMACY/DRUG STORES 11 KILO15 ALEX-MATROUH Agamy EL EZABY- SHOBRA 2 PHARMACY/DRUG STORES 113 SHOUBRA ST. SHOUBRA EL EZABY- ZAMALEK 2 PHARMACY/DRUG STORES 6A ELMALEK ELAFDAL ST. ZAMALEK KHAYRAT ZAMAN MARKET SUPERMARKETS HATEM ROUSHDY ST EL EZABY - MEET GHAM PHARMACY/DRUG STORES 37 ELMOQAWQS ST Meet Ghamr EL EZABY - ELMEHWAR PHARMACY/DRUG STORES PIECE 101,3RD DISTRICT,MEHWAR ELMARKAZY 6 OCTOBER EL EZABY - SUDAN PHARMACY/DRUG STORES 166 SUDAN ST. MOHANDSIN EV SPA / BEAUTY SERVICES 278 HEGAZ ST. EL HAY 7 HELIOPOLIS COLLECTION STARS TELECOMMUNICATION 39 SHERIF ST. DOWNTOWN SAMSUNG ASWAN APPLIANCE RETAIL SALAH ELDIN ST SALAH ELDIN ST GOLD LINE SHOP APPLIANCE RETAIL SALAH ELDIN ST SALAH ELDIN ST ELITE FOR SHOES ASWA FASHION RETAIL MALL ASWAN PLAZA MALL ASWAN PLAZA ALFA MARKET S3 SUPERMARKETS ETISALAT CO. EL TAGAMOA EL KHAMES -ELTESEEN ST- DOWN TOWN-NEW CAIRO ELSHEIBY FOOD RETAIL 124 MASR WEL SUDAN ST.HADDayek El koba Haddayek El koba ELSHEIBY 2 FOOD RETAIL 67 SAKR KORICH BLD.SHERATTON Sheratton - Helipolis SIR KIL BUSINESS SERVICES 328 EL NARGES BLD.