Resolving the Conflict Between Jewish and Secular Estate Law Benjamin C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TORAH TO-GO® Established by Rabbi Hyman and Ann Arbesfeld June 2017 • Shavuot 5777 a Special Edition Celebrating President Richard M

Rabbi Isaac Elchanan Theological Seminary Yeshiva University Center for the Jewish Future THE BENJAMIN AND ROSE BERGER TORAH TO-GO® Established by Rabbi Hyman and Ann Arbesfeld June 2017 • Shavuot 5777 A Special Edition Celebrating President Richard M. Joel WITH SHAVUOT TRIBUTES FROM Rabbi Dr. Kenneth Brander • Rabbi Dr. Hillel Davis • Rabbi Dr. Avery Joel • Dr. Penny Joel Rabbi Dr. Josh Joseph • Rabbi Menachem Penner • Rabbi Dr. Jacob J. Schacter • Rabbi Ezra Schwartz Special Symposium: Perspectives on Conversion Rabbi Eli Belizon • Joshua Blau • Mrs. Leah Nagarpowers • Rabbi Yona Reiss Rabbi Zvi Romm • Mrs. Shoshana Schechter • Rabbi Michoel Zylberman 1 Rabbi Isaac Elchanan Theological Seminary • The Benjamin and Rose Berger CJF Torah To-Go Series • Shavuot 5777 We thank the following synagogues which have pledged to be Pillars of the Torah To-Go® project Beth David Synagogue Green Road Synagogue Young Israel of West Hartford, CT Beachwood, OH Century City Los Angeles, CA Beth Jacob Congregation The Jewish Center Beverly Hills, CA New York, NY Young Israel of Bnai Israel – Ohev Zedek Young Israel Beth El of New Hyde Park New Hyde Park, NY Philadelphia, PA Borough Park Koenig Family Foundation Young Israel of Congregation Brooklyn, NY Ahavas Achim Toco Hills Atlanta, GA Highland Park, NJ Young Israel of Lawrence-Cedarhurst Young Israel of Congregation Cedarhurst, NY Shaarei Tefillah West Hartford West Hartford, CT Newton Centre, MA Richard M. Joel, President and Bravmann Family University Professor, Yeshiva University Rabbi Dr. Kenneth -

The Jewish Woman in a Torah Society

TEVES, 5735 I NOV.-DEC .. 1974 VOLUME X, NUMBERS 5-6 :fHE SIXTY FIVE CENTS The Jewish Woman in a Torah Society For Frustration or Fulfillment? Of Rights & Duties The Flame of Sara S chenirer The McGraw-Hill Anti-Sexism Memo ---also--- Convention Addresses by Senior Roshei Hayeshiva THE JEWISH OBSERVER in this issue ... OF RIGHTS AND DUTIES, Mordechai Miller prepared for publication by Toby Bulman.......................... 3 COMPLETENESS OF FAITH, based on an address by Rabbi Moshe Feinstein prepared for publication by Chaim Ehrman................... 5 CHUMASH: PREPARATION FOR OUR ENCOUNTER WITH THE WORLD, based on an address by Rabbi Yaakov Kamenetsky .................................. 8 SOME THOUGHTS ON MOSHIACH based on further remarks by Rabbi Kamenetsky ............... 9 PASSING THE TEST based on an address by Rabbi Yaakov Yitzchok Ruderman......................... I 0 JEWISH WOMEN IN A TORAH SOCIETY FOR FRUSTRATION? OR FULFILLMENT?, THE JEWISH OBSERVER is published monthly, except July and August, Nisson Wolpin ................. ............................................... 12 by the Agudath Israel of Amercia, 5 Beekman St., New York, N. Y. A FLAME CALLED SARA SCHENIRER, Chaim Shapiro 19 10038. Second class postage paid at New York, N. Y. Subscription: $6.50 per year; Two years, $11.00; BETH JACOB: A PICTORIAL FEATURE ........................ 24 Three years $15.00; outside of the United States $7 .50 per year. Single THE McGRAW HILL ANTI-SEXISM MEMO, copy sixty~five cents. Printed in the U.S.A. Bernard Fryshman ................................... .............. 26 RABBI N1ssoN WoLPIN MAN, a poem by Faigie Russak .......................................... 29 Editor Editorial Board WAITING FOR EACH OTHER DR. ERNST L. BODENHEIMER 30 Chairman a poem by Joshua Neched Yehuda .............................. RABBI NATHAN BULMAN RABBI JOSEPH ELIAS BOOK IN REVIEW: What ls the Reason - Vols. -

Chavrusa Pesach 2007

Rabbi Isaac Elchanan Theological Seminary A PUBLICATION OF THE RABBINIC ALUMNI OF THE RABBI ISAAC ELCHANAN THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY • AN AFFILIATE OF YESHIVA UNIVERSITY an affiliate of Yeshiva University Yeshiva University Center for the Jewish Future Max Stern Division of Communal Service 500 West 185th Street New York, NY 10033 CHAVRUSA APRIL 2007 • NISAN 5767 :dx ,ufr c–vrucjc tkt ,hbeb vru,v iht VOLUME 41 • NUMBER 3 CHAVRUSA is a publication of the Rabbinic Alumni of the Yeshiva Bids Rabbi Isaac Elchanan Theological Seminary- The Center for the Jewish Future, Farewell to an affiliate of Yeshiva University Rabbi Melech Richard M. Joel President Schachter z’l Rabbi Dr. Norman Lamm Chancellor, Yeshiva University somber and large crowd packed Rosh HaYeshiva, RIETS into the Nathan Lamport Rabbi Kenneth Brander Auditorium on February 27 Dean, Center for the 2006 to bid a kavod acharon Jewish Future A to Rabbi Dr. Melech Schachter z’l, a Rabbi Dr. Solomon Rybak beloved Colleague, Father, Zeide, Rebbe President, Rabbinic Alumni Rabbis Brander, Schachter, Genack and Twersky discuss their revered Rebbe. and Rosh Yeshiva. Among those who Rabbi Ronald L. Schwarzberg offered words of eulogy were RIETS Director, Jewish Career Development and Placement Rosh Hayeshiva and Yeshiva University CJF and Rabbinic Alumni Sponsor Chancellor Rabbi Dr. Norman Lamm Rabbi Elly Krimsky Assistant Director, Jewish Career ‘51R; Rabbi Zevulun Charlop ‘54R, the Development and Placement New York Premiere of Film and a Max and Marion Grill Dean of RIETS; Editor, Chavrusa Conversation on Rav Soloveitchik Rabbi Yisrael Meir Steinberg, Rabbi Rabbi Levi Mostofsky Schachter’s son in law; Rabbi Hershel Director of Rabbinic Programming n a scene at the end of “ Lonely Man 1985. -

PARSHA INSIGHTS by Rabbi Yaakov Asher Sinclair

SHABBAT PARSHAT VAYECHI 13 TEVET. 5779 – DECEMBER 21, 2018 VOL. 26 NO. 10 PARSHA INSIGHTS by Rabbi Yaakov Asher Sinclair With the Help of Heaven “And Yaakov lived in the land of Egypt…” (47:28) he Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions Land of Goshen. In spite of all of Yosef’s public movement is a global campaign promoting service to Egypt, rescuing the country from the ravages Tvarious forms of boycott against Israel until it of a world-wide famine and skillfully navigating Egypt meets what the campaign describes as "[Israel's] to a position of unrivalled prominence and power, we obligations under international law", defined as learn in the very first sentences of the book of Exodus withdrawal from the occupied territories, removal of that “a new king arose of Egypt, who did not know the separation barrier in the West Bank, full equality Yosef.” (1:8) Here is the archetypal source of the for Arab-Palestinian citizens of Israel, and promotion amnesia shown by host nations to their Jewish of the right of return of Palestinian refugees. citizens: They welcome our skills and industriousness Voices against the BDS movement claim that it judges and then turn around and say, “Yeah, but what have the State of Israel with standards different from those you done for us lately?” used to judge other political situations. For example, What causes this amnesia? Charles Krauthammer wrote: "Israel is the world's only 210 years later, when Moshe leads the Jewish People Jewish state. To apply to the state of the Jews a double out of Egypt, they were immersed in idol worship. -

The Price of Tea in China We've Done This Topic Before; We're Doing It Again

e"dl zyxt zay izrwªga-xda e"qyz xii` a"k May 19•20, '06 This Shabbat is the 229th day (of 354); the 33rd Shabbat (of 50) of 5766 • We read/learn the FIFTH perek of Pirkei Avot `:dk `xwie lr i"yx ?i©piq¦ xd© l¤v`¥ dH¨n¦ W§ o©i§pr¦ dn¨ The Price of Tea in China We've done this topic before; we're doing it again. A little differently, but again. And don't be surprised to see it every once in a while, each time A weekly feature of Torah Tidbits to help clarify practical dressed up differently, but essentially making the same point. Why the focus? and conceptual aspects of the Jewish Calendar, thereby Because the more Jews who get this point • and do something about it • thebetter fulfilling the mitzva of HaChodesh HaZeh Lachem... better things will be for Klal Yisrael and the closer we will be to the Geula. Clarification: [Bold statement, but I believe it with all my heart and soul • PC.] When Yom HaAtzmaut One of the colloquial expressions for "What does one thing have to do withfalls on Friday or Shabbat, the other?" is "What does that have to do with the price of tea (or rice) itin is pulled back to Thursday, lock•stock•and• China?" Hence, the title of this Lead Tidbit. If you look a little above the title barrel. That means not (in the hard copy or PDF version of TT), you will see the famous quote fromonly national ceremonies, observances, and festivi• Rashi, what does Shmita have to do with Har Sinai? The question is prompted ties, but davening and any other aspects by the unusual introductory pasuk, which instead of just saying, And G•dof a religious nature. -

Yeshiva of Ocean Catalog 2020-2021

YESHIVA OF OCEAN ♦♦♦ CATALOG 2020-2021 Table of Contents Board of Directors........................................................................................................................... 4 Administration ................................................................................................................................ 4 Faculty............................................................................................................................................. 4 History............................................................................................................................................. 5 Mission Statement ........................................................................................................................... 6 State Authorization and Accreditation ............................................................................................ 6 The Campus and Dormitory............................................................................................................ 6 Library............................................................................................................................................. 7 Textbook Information ..................................................................................................................... 8 General Information ........................................................................................................................ 8 Admissions Requirements ............................................................................................................. -

Derech Hateva 2018.Pub

Derech HaTeva A Journal of Torah and Science A Publication of Yeshiva University, Stern College for Women Volume 22 2017-2018 Co-Editors Elana Apfelbaum | Tehilla Berger | Hannah Piskun Cover & Layout Design Shmuel Ormianer Printing Advanced Copy Center, Brooklyn, NY 11230 Acknowledgements The editors of this year’s volume would like to thank Dr. Harvey Babich for the incessant time and effort that he devotes to this journal. Dr. Babich infuses his students with a passion for the Torah Umadda vision and serves as an exemplar of this philosophy to them. Through his constant encouragement and support, students feel confident to challenge themselves and find interesting connections between science and Torah. Dr. Babich, thank you for all the effort you contin- uously devote to us through this journal, as well as to our personal and future lives as professionals and members of the Jewish community. The publication of Volume 22 of this journal was made possible thanks to the generosity of the following donors: Dr. and Mrs. Harvey Babich Mr. and Mrs. Louis Goldberg Dr. Fred and Dr. Sheri (Rosenfeld) Grunseid Rabbi and Mrs. Baruch Solnica Rabbi Joel and Dr. Miriam Grossman Torah Activities Council YU Undergraduate Admissions We thank you for making this opportunity possible. Elana Apfelbaum Tehilla Berger Hannah Piskun Dedication We would like to dedicate the 22nd volume of Derech HaTeva: A Journal of Torah and Science to the soldiers of the Israel Defence Forces (IDF). Formed from the ashes of the Holocaust, the Israeli army represents the enduring strength and bravery of the Jewish people. The soldiers of the IDF have risked their lives to protect the Jewish nation from adversaries in every generation in wars such as the Six-Day War and the Yom Kippur War. -

Paying for Unused Articles by Freelance Writers and Journalists

Paying for Unused Articles by Freelance Writers and Journalists Rav Chaim Weg June 10, 2020 Case: A freelance writer was approached by several editors of a publication prior to the spread of Covid-19 to write some time-sensitive articles, such as spending Yom Tov in hotels, issues of safety during Lag B’omer trips, and having small weddings vs. large weddings. However, after these articles were written, the publication could not use them anymore since the subjects were entirely irrelevant due to the restrictions and lockdowns imposed because of Covid-19. Question: Who is responsible to bear the brunt of the financial loss in this case? Must the editors who hired the writer bear the loss and pay the writer the full agreed upon fee, or does the writer bear the loss and not receive payment for his work? Answer: We can analyze this case using the halachic principles of sechirus poalim, employee-employer relations, since the editor hired the writer to write the article. The Shulchan Aruch discusses two general types of models of sechirus poalim. The first one is where the employee is paid by the hour. In this case, if the employee works for a certain number of hours, he must be paid for his work, regardless of whether the employer actually benefits from the work or not. Therefore, the Shulchan Aruch states that even if someone hires another to work on an ownerless field or a field belonging to someone else, he must pay the employee for his labor. The second scenario discussed is that of a kablan, one who is paid by the job. -

Shavuos Schedule

SHAVUOS SCHEDULE EREV SHAVUOS • TUESDAY, JUNE 3RD Candlelighting ............................................................................. 8:26pm Mincha/ Maariv, (MS) ................................................................. 8:30pm Kiddush ...............................................................no earlier than 9:21pm SHAVUOS, DAY 1 • WEDNESDAY, JUNE 4TH All Night Torah Study (see inside for details) ................... 12:00am - 5:45am Teen Learning (YL) ............................................................12:00 - 2:30am Dancing at Dawn following learning ...........................................5:45am Early Shacharis, (MS) ...................................................................5:50am Shacharis, (MS) ............................................................................9:00am 9:00am Daily Minyan & Nine fif-TEEN Minyan ................. will not meet Youth Ice Cream Party, (YL) ......................................................... 4:30pm Early Mincha, (DM) .....................................................4:00pm & 5:00pm Father/Son Learning, (K) ............................................................. 5:30pm Mincha followed by Maariv, (MS) .............................................. 8:30pm Candlelighting and Kiddush .......................................not before 9:21pm SHAVUOS, DAY 2 • THURSDAY, JUNE 5TH Early Minyan, (K), Megillas Rus read, Yizkor recited ....................8:00am Main Minyan, (MS), Megillas Rus read, Yizkor at 10:20am .........8:30am 9:00am Minyan, (DM), -

The-Forum-Brochure-2018.Pdf

Saturday, February 10, 2018 • 7:30pm 26 Sh’vat, 5778 Havdallah: 7:45pm Katz JCC • 1301 Springdale Road • Cherry Hill, NJ Choose Classes & Register Online: katzjcc.org/forum $18 in advance / $25 at the door Advance registration is recommended, space is limited. Event Sponsor Gold Sponsor Silver Sponsors Alan & Helene In Honor of Rebbetzin Dinie Blumenfeld Mangel The Forum is made possible through the Community Shark Tank initiative of the Jewish Federation of Southern NJ and presented in partnership by: SESSION I: 8-8:45pm Hamantaschen Baking Hot Bench: You Be the Judge Debi Epstein, Congregation Sons of Israel / Mikvah Ohel Leah Shira Katz Scanlon, AJC, Jewish Community Relations Council Sweeten your celebration with new and different styles and fillings Share values, discuss ethics and take a first look into the Talmud, the while reviewing some of the timeless lessons of Purim with this codes and the wisdom of the Jewish legal process. Think you have all interactive and fun baking demo. the answers? You be the Judge! Jewish Learning Meets STEM: More Humor in the Talmud Hands-On Rituals For All Types Of Learners Rabbi Boaz Marmon, Temple Sinai Eliana Seltzer, Sherri Quinterro and Helene Sterling, Kellman Same title, new jokes! Investigate whether the Talmud/Talmudic Brown Academy figures are deliberately funny in spots or whether we sometimes Join the KBA teachers where ancient rituals and texts meet computer laugh at serious business. Either way, learn some Talmudic Rabbinic animated design software and 3D printers. Through discussion and tales that will certainly make you laugh and think. hands on learning, discover new ways of personalizing Jewish mitzvot. -

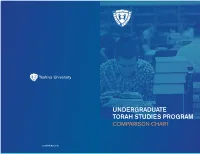

Undergraduate Torah Studies Program Comparison Chart

UNDERGRADUATE TORAH STUDIES PROGRAM COMPARISON CHART [email protected] UNDERGRADUATE TORAH STUDIES PROGRAMS COMPARISON CHART JSS IBC MYP SBMP FULL NAME James Striar School Isaac Breuer College Mazer Yeshiva Program Stone Beit Midrash Program Larger Beit Midrash (Chavrusa) / Classroom / LEARNING ENVIRONMENT Classroom Classroom / Small Beit Midrash Classroom Larger Beit Midrash (Chavrusa) LEVEL Beginner to Intermediate Intermediate to Advanced Intermediate to Advanced Intermediate to Advanced Foundations and Fundamentals. Broad and diverse range of study. Courses include Tanach (Bible), Courses include Tanach, Halacha, Gemara and Gemara, Halacha, FOCUS OF STUDY Jewish Thought, Jewish Law, Talmud, Jewish Thought, Analysis of Rishonim Jewish Thought, Tanach and Talmud Jewish History Sunday–Half Day Sunday–1.5 Hours DAILY SCHEDULE Monday–Thursday Monday–Thursday Monday–Thursday Monday–Thursday 4 Hours / Day 4.5 Hours / Day First Shiur (Misc. topics) Seder (Chavrusa) 9–10:30 a.m. 2-3 Hours / Day 9 a.m.–Noon 3 Hours / Day 9 a.m.–Noon Seder(Chavrusa) HOURLY SCHEDULE Lunch Break 9 a.m.–Noon (offers online and 10:30–11:45 a.m. Noon–1 p.m. night classes) Gemara Shiur Shiur (approximate) 11:45–12:55 p.m. 1–2:30 p.m. Followed by a lunch break DO STUDENTS GET COLLEGE CREDIT FOR THEIR TORAH Yes Yes Optional Optional STUDIES PROGRAM? Small Program First Year Chaburah Seminar; Sit at the feet of a Gadol BaTorah Balanced Program UNIQUE FEATURES Off-Campus Shabbatonim Honors Courses Frequent Shiur Events, Shabbatonim Special Night Seder Program and Holiday Programming Broad Course Offerings and Q & A with Rebbeim CLASS SIZE Small Small to Midsize Midsize Small to Large ALL PROGRAMS ARE STAFFED WITH REBBEIM AND MASHGICHIM who care about each talmid and forge life-long relationships with them, as well as extra-curricular programming (e.g., shabbatonim and shiur lunches). -

A Curriculum for Teaching Talmud

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Master's Theses Theses and Dissertations 1998 A Curriculum for Teaching Talmud Jeremy D. Neuman Loyola University Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_theses Part of the Education Commons Recommended Citation Neuman, Jeremy D., "A Curriculum for Teaching Talmud" (1998). Master's Theses. 4290. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_theses/4290 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 1998 Jeremy D. Neuman LOYOLA UNIVERSITY CHICAGO A CURRICULUM FOR TEACHING TALMUD A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS DEPARTMENT OF CURRICULUM, INSTRUCTION AND EDUCATIONAL PSYCHOLOGY BY JEREMY NEUMAN CHICAGO, ILLINOIS JANUARY, 1998 Copyright by Jeremy Neuman, 1998 All rights reserved. TABLE OF CONTENTS GLOSSARY ............................................................................................................... iv CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION TO THE TALMUD AND HOW IT IS TAUGHT TODAY .............................................................................................................. 1 2. BRUNER'S THEORIES ON THE PROCESS OF EDUCATION .............. 8 3. LESSON PLAN FOR TEACHING