Wildlife Express Newsletter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2020 Upland Game Bird Hunting Season Frameworks

Oregon Upland Game Bird Hunting Season Framework Effective dates: September 1, 2015 through August 31, 2020 Prepared by Wildlife Division Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife 4034 Fairview Industrial Dr SE Salem, Oregon 97302 Proposed 2015 -2020 Upland Game Bird Framework Executive Summary Oregon’s diverse habitats support 12 species of upland game birds, 8 of which are native, and 10 of which have hunting seasons. This document contains the proposed framework for upland game bird hunting seasons for the next five years. The seasons are designed to provide recreational hunting opportunities compatible with the overall status of upland game bird populations. The multi-year framework approach for setting upland game bird regulations was first adopted by the Oregon Fish and Wildlife Commission in 1996 for a 3-year period and again in 1999, 2004, and 2009 for 5-year periods. The role of regulations in game bird management has many functions including protection of a species, providing recreational opportunities, and in consultation with hunters to provide bag limits and seasons. Regulations should be as simple as possible to make them easy to understand. These frameworks are also based on the concept that annual fluctuations in upland bird numbers, which can vary greatly and are normal, should not be the basis for setting hunting seasons year by year. Standardized frameworks are biologically sound management tools that help the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife (Department) provide consistent, stable regulations that reduce confusion, assist hunters with planning trips, and lower administrative costs. In an effort to stabilize hunting regulations, the following concepts are the foundation for the frameworks offered in this document: Many upland game bird populations exhibit a high annual death rate and cannot be stockpiled from year to year Similar annual death rates occur in most upland game bird populations whether they are hunted or not. -

BLUE GROUSE and RUFFED GROUSE (Dendragapus Obscurus and Bonasa Umbellus)

Chapter 13 BLUE GROUSE AND RUFFED GROUSE (Dendragapus obscurus and Bonasa umbellus) Harry Harju I. CENSUS – A. Production Surveys – 1. Rationale – Random brood counts are a survey method used to assess the reproductive success of blue or ruffed grouse. Unfortunately, these counts are done too late in the year to be considered in setting or adjusting hunting seasons. If the sample size is large enough, the counts can help identify important habitats used by broods and can provide insight to the potential quality of hunting in the fall. 2. Application – Random brood counts can be conducted on foot, from horseback or from a vehicle and should cover all portions of the brood-rearing area. A good pointing dog is invaluable to locate broods. If a flushing dog is used, it should be trained to walk very close to the observer. Each time a grouse is seen, record the species, location, age, sex and habitat on a wildlife observation form. If a count is incomplete, circle the number of birds recorded. The time frame for these surveys is July 15 to August 31. Warm, clear days are best for brood counts. The best results are obtained by searching for broods in the first two and last three hours of daylight. When a well-trained dog is used, counts can be conducted throughout the day. 3. Analysis of Data – Refer to chapter 12 (Sage-grouse), Section II.B (Brood Production). 4. Disposition of Data – All records of brood observations are forwarded to Regional Wildlife Management Coordinators for proofing, and then entered into the Wildlife Observation System Database. -

11 Blue Grouse

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Grouse and Quails of North America, by Paul A. Johnsgard Papers in the Biological Sciences May 2008 11 Blue Grouse Paul A. Johnsgard University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/bioscigrouse Part of the Ornithology Commons Johnsgard, Paul A., "11 Blue Grouse" (2008). Grouse and Quails of North America, by Paul A. Johnsgard. 13. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/bioscigrouse/13 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Papers in the Biological Sciences at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Grouse and Quails of North America, by Paul A. Johnsgard by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Blue Grouse Dendragapw obsctlrus (Say) 182 3 OTHER VERNACULAR NAMES @USKY grouse, fool hen, gray grouse, hooter, mountain grouse, pine grouse, pine hen, Richardson grouse, sooty grouse. RANGE From southeastern Alaska, southern Yukon, southwestern Mackenzie, and western Alberta southward along the offshore islands to Vancouver and along the coast to northern California, and in the mountains to southern California, northern and eastern Arizona, and west central New Mexico (A.O.U. Check-list). SUBSPECIES (ex A.O.U. Check-list) D. o. obscurus (Say): Dusky blue grouse. Resident in the mountains from central Wyoming and western South Dakota south through eastern Utah and Colorado to northern and eastern Arizona and New Mexico. D. o. sitkensis Swarth: Sitkan blue grouse. Resident in southeastern Alaska south through the coastal islands to Calvert Island and the Queen Charlotte Islands, British Columbia. -

Observation on a Sooty Grouse Population at Sage Hen Creek

THE CONDOR--- VOLUME 58 SEPTEMBER-OCTOBER, 1956 NUMBER 5 OBSERVATIONS ON A SOOTY GROUSE POPULATION AT SAGE HEN CREEK, CALIFORNIA By ROBERT S. HOFFMANN In recent years there has been considerable interest in two separate aspects of the biology of Blue Grouse (Dendragapus) . The first of these is the controversy concerning their taxonomy. The genus is widely distributed in the coniferous forests of the western states and consists of two groups of races recognized by some as separate species: the fuliginosus group, or Sooty Grouse, along the Pacific coast, and the obscures group, or Dusky Grouse, in the Great Basin and Rocky Mountain areas. Originally these two groups were placed under the name Dendragapus obscurus on the basis of supposed intergradation (Bendire, 1892:41,44, SO). The work of Brooks (1912,1926,1929) and Swarth (1922, 1926), however, led to their separation in the fourth edition of the A.O.U. Check-list (1931) into coastal and interior species. This split stood until the publication of the 19th Supplement to the A.O.U. Check-list (1944) when, following Peters (1934), D. fuliginosus and its subspecieswere replaced under D. obscurus. Al- though at that time some doubt was still expressedabout the correctnessof this merger (Grinnell and Miller, 1944: 113), intergradation in northern Washington and southern British Columbia between the races fuliginosus and pallidus has now been reported by several authors (Munro and Cowan, 1947:89; Carl, Guiguet, and Hardy, 1952:86; Jewett, Taylor, Shaw, and Aldrich, 1953 : 200). The taxonomy of these grouse must rest upon the fact of intergradation between the two groups of races. -

Dusky Grouse Tend to Be Adapted Dusky and Sooty Grouse Were Considered Distinct

Volt.un£ 14 .Numkt 3 9all2006 Blue Grouse divided by two equals Dusky and Sooty Grouse Michael A. Schroeder, Upland Bird Research Biologist Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife P.O. Box 1077 Bridgeport, W A 98813 email: [email protected] The state of Washington has a new species of grouse, at least forested habitats throughout the year, it appears to be according to the American Ornithologists Union (Auk, 2006, vulnerable to variations in forest practices. For example, Pages 926-936). Dendragapus obscurus (formerly known as research on Sooty Grouse in British Columbia indicated that the Blue Grouse) has now been split into 2 species based on their populations fluctuated dramatically depending on the genetic, morphological, and behavioral evidence; the Dusky age of the forest following clear-cutting. Unfortunately, there Grouse (Dendragapus obscurus) and the Sooty Grouse has been little effort to evaluate the relationship between (Dendragapus fuliginosus). This split is actually a reversion forest management practices and Sooty Grouse populations. to the previous situation during the early 1900s when the In contrast to Sooty Grouse, Dusky Grouse tend to be adapted Dusky and Sooty Grouse were considered distinct. to relatively open habitats in forest openings or close to forest edges. Because these open habitats are preferred areas for As a group, Dusky and Sooty Grouse are widely distributed livestock production and development, it is necessary to in the mountainous portions of western North America. understand the relationships between land use and grouse Although they generally winter in coniferous forest, their populations. The human population increase in the breeding breeding habitats are quite varied. -

Alpha Codes for 2168 Bird Species (And 113 Non-Species Taxa) in Accordance with the 62Nd AOU Supplement (2021), Sorted Taxonomically

Four-letter (English Name) and Six-letter (Scientific Name) Alpha Codes for 2168 Bird Species (and 113 Non-Species Taxa) in accordance with the 62nd AOU Supplement (2021), sorted taxonomically Prepared by Peter Pyle and David F. DeSante The Institute for Bird Populations www.birdpop.org ENGLISH NAME 4-LETTER CODE SCIENTIFIC NAME 6-LETTER CODE Highland Tinamou HITI Nothocercus bonapartei NOTBON Great Tinamou GRTI Tinamus major TINMAJ Little Tinamou LITI Crypturellus soui CRYSOU Thicket Tinamou THTI Crypturellus cinnamomeus CRYCIN Slaty-breasted Tinamou SBTI Crypturellus boucardi CRYBOU Choco Tinamou CHTI Crypturellus kerriae CRYKER White-faced Whistling-Duck WFWD Dendrocygna viduata DENVID Black-bellied Whistling-Duck BBWD Dendrocygna autumnalis DENAUT West Indian Whistling-Duck WIWD Dendrocygna arborea DENARB Fulvous Whistling-Duck FUWD Dendrocygna bicolor DENBIC Emperor Goose EMGO Anser canagicus ANSCAN Snow Goose SNGO Anser caerulescens ANSCAE + Lesser Snow Goose White-morph LSGW Anser caerulescens caerulescens ANSCCA + Lesser Snow Goose Intermediate-morph LSGI Anser caerulescens caerulescens ANSCCA + Lesser Snow Goose Blue-morph LSGB Anser caerulescens caerulescens ANSCCA + Greater Snow Goose White-morph GSGW Anser caerulescens atlantica ANSCAT + Greater Snow Goose Intermediate-morph GSGI Anser caerulescens atlantica ANSCAT + Greater Snow Goose Blue-morph GSGB Anser caerulescens atlantica ANSCAT + Snow X Ross's Goose Hybrid SRGH Anser caerulescens x rossii ANSCAR + Snow/Ross's Goose SRGO Anser caerulescens/rossii ANSCRO Ross's Goose -

Blue Grouse Ecology and Habitat Requirements in North Central Utah

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU All Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies 5-1972 Blue Grouse Ecology and Habitat Requirements in North Central Utah David A. Weber Utah State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd Part of the Life Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Weber, David A., "Blue Grouse Ecology and Habitat Requirements in North Central Utah" (1972). All Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 3512. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd/3512 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would hke to express my sincere appreciation to Dr. J. B. Low, leader of the Utah Cooperative Wildlife Research Unit, for giving me the opportunity to work on this project and for his continuing guidance and patience during the study. I would also like to thank the members of my graduate committee: Dr. Donald Davis, Dr. Arthur Holmgren, and Dr. William Sigler for their advice and assis tance in many ways during the two years of the research. Frank Gunnell and Bruce Reese of the U. S. Forest Service deserve special thanks for many hours of help in the field and for continuing constructive criticism. Jack Rensel, Clair Huff, and John Kimball of the Utah Division of Wildlife Resources also provtded field assistance and suggestions during the course of the study. I very much appreciate the help and advice of my co-worker during 19 71, J:!arry l:larnes, and wish him well in his continuing studies of the blue grouse. -

Forest Grouse

Volume 34 | Issue 2 October 2020 FOREST GROUSE Dusky GrouseCCBY Paul Hurtado Flickr Inside: Meet the Grouse Moving Up Leaving Home Hey Baby... Be Outside! idfg.idaho.gov Meet the Grouse If so, Have you ever had a quiet hike interrupted by an exploding bird? you have met a member of the grouse family. While they do not really explode, their sudden get-away right at your feet seems like a feathered explosion. In fact, this sudden rapid flight is common in this group of birds. Their short, rounded wings can beat very fast. This lets the bird suddenly fly into the air. Just like it startles you, it can also startle a predator just long enough for the bird to fly away to safety. Grouse belong to a large group of birds called “galliforms.” This group is often referred to as upland game birds. It includes birds like turkeys, quail, and grouse. They are all ground-dwelling birds that feed mostly on plants and insects. About 183 species of these birds live around the world. They are found everywhere except Antarctica and South America. Twelve species of galliforms are native to North America. Here in Idaho, we have five native grouse species. Several other species of galliform birds live in Idaho, but they were introduced as game birds for hunting. Upland game birds are well camouflaged. Their colors are mainly brown, tan, buff, gray, black, and white. Because they spend a lot of time on the ground, being camouflaged is very important. Three members of this group, called ptarmigan (TAR-mi-gan), even turn white in the winter. -

Colorado Birds the Colorado Field Ornithologists’ Quarterly

Vol. 45 No. 3 July 2011 Colorado Birds The Colorado Field Ornithologists’ Quarterly Remembering Abby Modesitt Chipping Sparrow Migration Sage-Grouse Spermatozoa Colorado Field Ornithologists PO Box 643, Boulder, Colorado 80306 www.cfo-link.org Colorado Birds (USPS 0446-190) (ISSN 1094-0030) is published quarterly by the Colo- rado Field Ornithologists, P.O. Box 643, Boulder, CO 80306. Subscriptions are obtained through annual membership dues. Nonprofit postage paid at Louisville, CO. POST- MASTER: Send address changes to Colorado Birds, P.O. Box 643, Boulder, CO 80306. Officers and Directors of Colorado Field Ornithologists: Dates indicate end of current term. An asterisk indicates eligibility for re-election. Terms expire 5/31. Officers: President: Jim Beatty, Durango, 2013; [email protected]; Vice President: Bill Kaempfer, Boulder, 2013*; [email protected]; Secretary: Larry Modesitt, Greenwood Village, 2013*; [email protected]; Treasurer: Maggie Boswell, Boulder, 2013; trea- [email protected] Directors: Lisa Edwards, Falcon, 2014*; Ted Floyd, Lafayette, 2014*; Brenda Linfield, Boulder, 2013*; Christian Nunes, Boulder, 2013*; Bob Righter, Denver, 2012*; Joe Roller, Denver, 2012* Colorado Bird Records Committee: Dates indicate end of current term. An asterisk indicates eligibility to serve another term. Terms expire 12/31. Chair: Larry Semo, Westminster; [email protected] Secretary: Doug Faulkner, Arvada (non-voting) Committee Members: John Drummond, Monument, 2013*; Peter Gent, Boulder, 2012; Bill Maynard, Colorado Springs, 2013; Bill Schmoker, Longmont, 2013*; David Silver- man, Rye, 2011*; Glenn Walbek, Castle Rock, 2012* Colorado Birds Quarterly: Editor: Nathan Pieplow, [email protected] Staff: Glenn Walbek (Photo Editor), [email protected]; Hugh Kingery (Field Notes Editor), [email protected]; Tony Leukering (In the Scope Editor), GreatGrayOwl@aol. -

A Check-List and Bibliography of Hybrid Birds in North America North of Mexico

A CHECK-LIST AND BIBLIOGRAPHY OF HYBRID BIRDS IN NORTH AMERICA NORTH OF MEXICO BY E. LENDELL COCKKUM RNST MAYR (1942:257-270) has d ’rscussed in detail some of the philo- E sophical implications of hybridism. He points out, for example, that: “In birds, we have a fair amount of information, since some collectors, sensing their scarcity value, have specialized in the collecting of hybrids, and amateur observers have always been fascinated by them. We can state, on the basis of the data collected by these naturalists, that sympatric hybrids are found pri- marily in genera in which copulation is not preceded by pair formation and an engagement‘ period ’ [p. 2611 . Hybrids occur much more rarely among pair-forming species of birds. In such cases the male and female have com- mitted not only an original mistake,‘ ’ but have apparently not corrected‘ ’ it afterwards by abandoning the brood [p. 2621.” In spite of the increased interest in hybridism in birds in recent years, no attempt has been made to compile the many scattered references and reports of hybrids into a single paper since the early compilation by Suchetet (1897). In that classic Suchetet attempted to list all known cases of hybrids in birds. Unfortunately his work is not readily available to most ornithologists in this country. My attempt to compile known cases of hybrids in birds has been made with three important restrictions : First, I have listed only those cases in which the hybrids presumably resulted from crosses in nature. If hybrids resulting from birds in captivity were listed, the list would be much larger, especially among the ducks and geese (see Ball, 1934:24; Sibley, 1938:327-335; Kortright, 1942 :43-44; and Delacour and Mayr, 1945:3-55). -

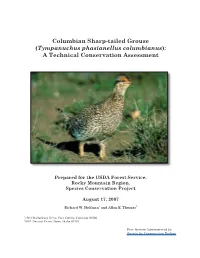

Columbian Sharp-Tailed Grouse (Tympanuchus Phasianellus Columbianus): a Technical Conservation Assessment

Columbian Sharp-tailed Grouse (Tympanuchus phasianellus columbianus): A Technical Conservation Assessment Prepared for the USDA Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Region, Species Conservation Project August 17, 2007 Richard W. Hoffman1 and Allan E. Thomas2 11804 Wallenberg Drive, Fort Collins, Colorado 80526 25001 Decatur Drive, Boise, Idaho 83704 Peer Review Administered by Society for Conservation Biology Hoffman, R.W. and A.E. Thomas. (2007, August 17). Columbian Sharp-tailed Grouse (Tympanuchus phasianellus columbianus): a technical conservation assessment. [Online]. USDA Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Region. Available: http://www.fs.fed.us/r2/projects/scp/assessments/columbiansharptailedgrouse.pdf [date of access]. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The authors thank K.J. Eichhoff and H.E. Vermillion of the Colorado Division of Wildlife for their assistance in preparing the figures and C.E. Soldati, a student at Colorado State University, for her help in preparing the References section. J.A. Boss, librarian for the Colorado Division of Wildlife, was extremely helpful in locating and obtaining many of the references used to prepare this assessment. T.P. Woolley, biologist with the Wyoming Game and Fish Department, provided lek survey data and answered many questions regarding the distribution and management of Columbian sharp-tailed grouse in Wyoming. This assessment also benefited from information provided by A.D. Apa, M.A. Schroeder, and A.W. Spaulding. D.P. McDonald of the University of Wyoming conducted the lifecycle model analyses and prepared the summary of the results. C.E. Braun and an anonymous reviewer provided constructive comments that substantially improved the quality of the assessment. Finally, the authors are extremely grateful to G.D. -

Blue Grouse (Dendragapus Obscurus)

Blue Grouse (Dendragapus obscurus) (Recently split to include Sooty Grouse and Dusky Grouse. Dusky Grouse breeds in New Mexico) NMPIF level: Biodiversity Conservation Concern, Level 2 (BC2) NMPIF assessment score: 13 NM stewardship responsibility: Low National PIF status: Watch List New Mexico BCRs: 16, 34 Primary breeding habitat(s): Mixed Conifer Forest Other habitats used: Spruce-fir Forest, Ponderosa Pine Forest Summary of Concern Blue Grouse reaches the southern terminus of its range in montane forest areas of northern and central New Mexico. Range-wide the species has shown significant and long-term population declines; little is known about trends in New Mexico populations. Associated Species Northern Goshawk, Northern Saw-whet Owl, Broad-tailed Hummingbird (SC2), Red-naped Sapsucker (SC2), Three-toed Woodpecker, Olive-sided Flycatcher (BC2), Western Wood-Pewee, Warbling Vireo (SC2), Pine Grosbeak, Evening Grosbeak Distribution Blue Grouse is primarily a species of the northern Rockies, and north-coastal mountains and forests. Its year-round range extends from Alaska and northwestern Canada south into the United States along the Rocky Mountain and Cascade/Sierra Nevada chains. Coastal and interior populations are considered separate subspecies. Isolated populations extend as far south as southern Arizona and New Mexico (Zwickel 1992). In New Mexico, Blue Grouse is a rare resident in the Sangre de Cristo, San Juan, and Jemez mountains. It is very rare in isolated western ranges south to the Mogollons (Hubbard 1978, Parmeter et al. 2002). Ecology and Habitat Requirements Blue Grouse breeds in montane forest communities with relatively open tree canopies, and may occupy adjacent shrub-steppe habitat out to 2 kilometers from the forest edge.