1 Prague, June 22-26, 2015

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Object Frieze in the Burial Chamber of the Late Period Shaft Tomb of Menekhibnekau at Abusir 76 LADISLAV BAREŠ

INSTITUT DES CULTURES MÉDITERRANÉENNES ET ORIENTALES DE L’ACADÉMIE POLONAISE DES SCIENCES ÉTUDES et TRAVAUX XXVI 2013 LADISLAV BAREŠ Object Frieze in the Burial Chamber of the Late Period Shaft Tomb of Menekhibnekau at Abusir 76 LADISLAV BAREŠ Object friezes, containing a broad range of different items, such as crowns, staves, royal insignia, clothing, jewellery, weapons, ritual objects, amulets, tools, etc., appear rather frequently on the sides of wooden coffi ns or, much rarely, on the sides of the burial cham- bers dating especially from the later part of the Old Kingdom until the end of the Middle Kingdom. Less often, they are attested during the New Kingdom and even later.1 In some cases, they are only painted; otherwise their names are added as well. Sometimes, more items of one and the same kind are mentioned or a digit is added, clearly intending to enhance their magical powers for the deceased. Although the object frieze is, exceptionally, attested later, namely during the New Kingdom in scenes of the funeral outfi t or the deceased overseeing it (e.g. TT 79: Menche- perre-seneb)2 and even the Late Period (TT 33: Padiamenopet),3 its use in the tombs of such a date seemed to have been limited to the Theban region so far. Recently, however, such friezes have also been found in the large Late Period shaft tombs at Abusir, dated to the very end of the Twenty-sixth or even the beginning of the Twenty-seventh Dynasty, namely those of Iufaa4 and Menekhibnekau.5 In the tomb of Iufaa, several short object friezes (containing up to ten items as a maximum) appear on the outer side of the lid of the anthropoid inner sarcophagus, in the head region, as well as on the northern and southern sides of the depression inside the outer sarcophagus (close to its western, i.e. -

“Funerary Boats and Boat Pits of the Old Kingdom.” Abusir and Saqqara In

ARCHIV ORIENTALNf Quarterly Journal of African and Asian Studies Volume 70 Number 3 August 2002 PRAHA ISSN 0044-8699 Archiv orientalni Quarterly Journal of African and Asian Studies Volume 70 (2002) No.3 Abusir and Saqqara in the Year 2001 Proceedings of the Symposium (Prague, September 25th-27th, 2001) - Bdited by Filip Coppens, Czech National Centre of Bgyptology Contents Opening Address (LadisZav BareS) . .. 265-266 List of Abbreviations 267-268 Hartwig AZtenmiiller: Funerary Boats and Boat Pits of the Old Kingdom 269-290 The article deals with the problem of boats and boat pits of royal and non-royal provenance. Start- ing from the observation that in the Old Kingdom most of the boats from boat gra ves come in pairs or in a doubling of a pair the boats of the royal domain are compared with the pictorial representa- tions of the private tombs of the Old Kingdom where the boats appear likewise in pairs and in ship convoys. The analysis of the ship scenes of the non-royal tomb complexes of the Old Kingdom leads to the result that the boats represented in the tomb decoration of the Old Kingdom are used during the night and day voyage of the tomb owner. Accordingly the ships in the royal boat graves are considered to be boats used by the king during his day and night journey. MirosZav Barta: Sociology of the Minor Cemeteries during the Old Kingdom. A View from Abusir South 291-300 In this contribution, the Abusir evidence (the Fetekty cemetery from the Late Fifth Dynasty) is used to demonstrate that the notions of unstratified cemeteries for lower rank officials and of female burials from the residential cemeteries is inaccurate. -

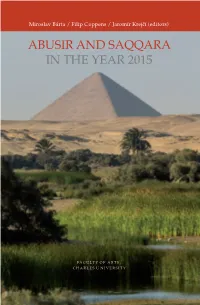

Catalogue Publications Czech Institute of Egyptology

Catalogue Publications Czech Institute of Egyptology Miroslav Bárta – Filip Coppens – Jaromír Krejčí (eds.) Abusir and Saqqara in the Year 2015 Charles University, Fauclty of Arts, Prague 2017 695 pages, 30 cm The Czech Institute of Egyptology of the Charles University in Prague has since the start of the third millennium established the tradition of organizing on a regular basis a platform for scholars, active in the pyramid fields and the cemeteries of the Memphite region (Abusir, Saqqara, Dahshur and Giza in particular), to meet, exchange information and establish further cooperation. The present volume, containing 43 contributions by 53 scholars, is the result of the already fourth “Abusir and Saqqara” conference held in June 2015. The volume reflects the widespread, often multidisciplinary interest of many researchers into a wide variety of different topics related to the Memphite necropoleis. Recurring topics of the studies include a focus on archaeology, the theory of artifacts, iconographic and art historian studies, and the research of largely unpublished archival materials. An overwhelming number of contributions (31) is dedicated to various aspects of Old Kingdom archaeology and most present specific aspects linked with archaeological excavations, both past and present. 190 EUR (4864 CZK) Miroslav Verner Abusir XXVIII. The Statues of Raneferef and the Royal Sculpture of the Fifth Dynasty Charles University in Prague, Faculty of Arts, Prague 2017 259 pages, 31 cm Czech archaeological team discovered in the mortuary temple of Raneferef in Abusir in the 1980s fragments of about a dozen of the statues of the king, including his six complete likenesses. The monograph presents a detailed description and discussion of Raneferef’s statues in the broader context of the royal sculpture of the Fifth Dynasty. -

THE ARCHAEOLOGY of ACHAEMENID RULE in EGYPT by Henry Preater Colburn a Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requ

THE ARCHAEOLOGY OF ACHAEMENID RULE IN EGYPT by Henry Preater Colburn A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Classical Art and Archaeology) in the University of Michigan 2014 Doctoral Committee: Professor Margaret C. Root, Chair Associate Professor Elspeth R. M. Dusinberre, University of Colorado Professor Sharon C. Herbert Associate Professor Ian S. Moyer Professor Janet E. Richards Professor Terry G. Wilfong © Henry Preater Colburn All rights reserved 2014 For my family: Allison and Dick, Sam and Gabe, and Abbie ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This dissertation was written under the auspices of the University of Michigan’s Interdepartmental Program in Classical Art and Archaeology (IPCAA), my academic home for the past seven years. I could not imagine writing it in any other intellectual setting. I am especially grateful to the members of my dissertation committee for their guidance, assistance, and enthusiasm throughout my graduate career. Since I first came to Michigan Margaret Root has been my mentor, advocate, and friend. Without her I could not have written this dissertation, or indeed anything worth reading. Beth Dusinberre, another friend and mentor, believed in my potential as a scholar well before any such belief was warranted. I am grateful to her for her unwavering support and advice. Ian Moyer put his broad historical and theoretical knowledge at my disposal, and he has helped me to understand the real potential of my work. Terry Wilfong answered innumerable questions about Egyptian religion and language, always with genuine interest and good humor. Janet Richards introduced me to Egyptian archaeology, both its study and its practice, and provided me with important opportunities for firsthand experience in Egypt. -

Miroslav Barta – Vladimir Bruna

METODOLOGY PES XXV/2020 7 Map of archaeological features in Abusir1 Miroslav Bárta – Vladimír Brůna – Ladislav Bareš – Jaromír Krejčí – Veronika Dulíková – Martin Odler – Hana Vymazalová With interruptions, the archaeological site of Abusir MAP OF ARCHAEOLOGICAL FEATURES has been explored for more than a century. The main expeditions that have worked there under the guidance The history of the numbering of archaeological features of Ludwig Borchardt, Georg Steindorff, Zbyněk Žába, in the Abusir area can be traced back to the first Miroslav Verner or Miroslav Bárta (ongoing) used excavations by John Shae Perring, who documented different approaches to the identification and cataloguing the internal spaces of Abusir’s three main pyramids in of the individual features. This article aims to provide 1838. A Prussian expedition headed by Karl Richard all interested parties with necessary concordance to Lepsius followed in 1842–1843. He made a numbered the current method of numbering and registration of list of Egyptian pyramids including those in Abusir, but archaeological features and a notion of their positions some of his identifications are mistaken. Lepsius also within the site. Majority of principal structures and examined a tomb in Abusir South built for overseer pyramid complexes have been published or are currently of the magazines and property custodian of the king, being prepared for publication in the monograph series Fetekti (AS 5). The first brief excavation of Ptahshepses’ Abusir. Many minor features whose processing is mastaba -

Shabtis of Egyptian Officers from the Late Period in the Collections of the Institute of Classical Archaeology in Prague

STUDIA HERCYNIA XXI/1, 79–85 Shabtis of Egyptian Officers from the Late Period in the Collections of the Institute of Classical Archaeology in Prague Pavel Onderka ABSTRACT The Institute of Classical Archaeology in Prague hosts a small collection of Egyptian antiquities. It includes four funerary figurines, termed “shabtis” in Egyptian archaeology, that originate in the funerary equipment of two Egyptian officers of the Late Period (715–332 BCE) – Padihorenpe and Nekawnebpehty. KEYWORDS Shabtis; Late Period Egypt; ancient Egyptian military. INTRODUCTION The Institute of Classical Archaeology, Faculty of Arts, Charles University in Prague, hosts a small but highly interesting collection of Egyptian antiquities comprising several dozens of objects (cf. Dufková – Ondřejová eds. 2006, 141–143). The collection mainly includes bronze statuettes,1 terracotta figurines (Smoláriková 2010, cat. nos. 4, 15, 23, 38, 39 and 55), amulets made of Egyptian faïence,2 and last but not least shabtis (Onderka et al. 2003, 157). No records of how the shabtis became part of the Institute’s collection are currently available. A shabti ([SAbty], shawabty [SAwAbty], or ushabti [wSbty]) is a type of ancient Egyptian funerary figurine, which developed during the Middle Kingdom (ca. 2055–1650 BCE) from models of funerary estates and funerary statues. During the New Kingdom (ca. 1543–1069 BCE), their numbers rose from a couple to over 400 in each set of funerary equipment (365 for each day of the year, 36 foremen for each decan [a ten day period] and several scribes and “managing staff”). They continued to be used until the Ptolemaic Period (332–30 BCE;Milde 2012, 3). -

Abusir and Saqqara in the Year 2015 Sa Qq a R a Nd Abusir Ye a R 2015 in the a Čí Árt Oppens V B Ír Kre J (Editors) (Editors) Ro M Filip C Filip a J Mirosl A

Miroslav Bárta / Filip Coppens / Jaromír Krejčí (editors) A ABUSIR AND SAQQARA R A IN THE YEAR 2015 QQ SA R 2015 A ND A ABUSIR YE IN THE A ČÍ J ÁRT B OPPENS V C ÍR KRE A (EDITORS) (EDITORS) M RO FILIP FILIP A J MIROSL ISBN 978-80-7308-758-6 FA CULTY OF ARTS, C H A RLES U NIVERSITY AS_vstupy_i_xxiv_ABUSIR 12.1.18 13:34 Stránka i ABUSIR AND SAQQARA IN THE YEAR 2015 AS_vstupy_i_xxiv_ABUSIR 12.1.18 13:34 Stránka ii ii Table Contens The publication was compiled within the framework of the Charles University Progress project Q11 – “Complexity and resilience. Ancient Egyptian civilisation in multidisciplinary and multicultural perspective”. AS_vstupy_i_xxiv_ABUSIR 12.1.18 13:34 Stránka iii Table Contens iii ABUSIR AND SAQQARA IN THE YEAR 2015 Miroslav Bárta – Filip Coppens – Jaromír Krejčí (editors) Faculty of Arts, Charles University Prague 2017 AS_vstupy_i_xxiv_ABUSIR 12.1.18 13:34 Stránka iv iv Table Contens Reviewers Ladislav Bareš, Nigel Strudwick Contributors Katarína Arias Kytnarová, Miroslav Bárta, Edith Bernhauer, Vivienne Gae Callender, Filip Coppens, Jan-Michael Dahms, Vassil Dobrev, Veronika Dulíková, Andres Diego Espinel, Laurel Flentye, Zahi Hawass, Jiří Janák, Peter Jánosi, Lucie Jirásková, Mohamed Ismail Khaled, Evgeniya Kokina, Jaromír Krejčí, Elisabeth Kruck, Hella Küllmer, Audran Labrousse, Renata Landgráfová, Rémi Legros, Radek Mařík, Émilie Martinet, Mohamed Megahed, Diana Míčková, Hassan Nasr el-Dine, Hana Navratilová, Massimiliano Nuzzolo, Martin Odler, Adel Okasha Khafagy, Christian Orsenigo, Robert Parker, Stephane Pasquali, Dominic Perry, Marie Peterková Hlouchová, Patrizia Piacentini, Gabriele Pieke, Maarten J. Raven, Joanne Rowland, Květa Smoláriková, Saleh Soleiman, Anthony J. -

Ägyptisches Museum, Berlin

1 Berlin, Ägyptisches Museum Past and present members of the staff of the Topographical Bibliography of Ancient Egyptian Hieroglyphic Texts, Statues, Reliefs and Paintings, especially R. L. B. Moss, E. W. Burney and Jaromir Malek, have taken part in the preparation of this list at the Griffith Institute, University of Oxford This pdf version (situation on 17 January 2012): Elizabeth Fleming, Alison Hobby and Diana Magee (Assistants to the Editor) and Tracy Walker Thebes. TT 1. Sennedjem. Dyn. XIX. i2.5 Outer coffin of woman, Tamakhet, in Berlin, Ägyptisches Museum, 10832. Aeg. Inschr. ii, 323-9; Ausf. Verz. 174. Thebes. TT 1. Sennedjem. Dyn. XIX. i2.5 Inner coffin lid of Tamakhet, in Berlin, Ägyptisches Museum, 10859. Alterthümer pl. 28; Ausf. Verz. 174-5. Thebes. TT 1. Sennedjem. Dyn. XIX. i2.5 Box of son, Ramosi, in Berlin, Ägyptisches Museum, 10195. Kaiser, Äg. Mus. Berlin (1967), Abb. 582; Aeg. Inschr. ii, 274; Ausf. Verz. 197. Thebes. TT 2. Khabekhnet. i2.7 Relief, Kings, etc., in Berlin, Ägyptisches Museum, 1625. L. D. ii. 20; Aeg. Inschr. ii, 190-2; Ausf. Verz. 155-6. <<>> Thebes. TT 23. Thay. i2.40(31)-(32) Relief, deceased with Western goddess, in Berlin, Ägyptisches Museum, 14220 (lost). Scharff, Götter Aegpytens, pl. 32; Aeg. Inschr. ii, 218; Ausf. Verz. 148. Thebes. TT 34. Mentuemhet. i2.61 Statue-group of three ape-guardians, dedicated by deceased, formerly in Bissing colln., then in The Hague, Scheurleer Museum, now in Berlin, Ägyptisches Museum, 23729. Topographical Bibliography of Ancient Egyptian Hieroglyphic Texts, Statues, Reliefs and Paintings Griffith Institute, Sackler Library, 1 St John Street, Oxford OX1 2LG, United Kingdom [email protected] 2 Ä.Z. -

Egypt and Sudan: Old Kingdom to Late Period

World Archaeology at the Pitt Rivers Museum: A Characterization edited by Dan Hicks and Alice Stevenson, Archaeopress 2013, pages 90-114 6 Egypt and Sudan: Old Kingdom to Late Period Elizabeth Frood 6.1 Introduction This chapter considers the archaeological material held by the Pitt Rivers Museum (PRM) from Egypt and Sudan that dates from the beginning of the Old Kingdom (Fourth Dynasty, from c. 2575 BCE) to the end of the Late Period (i.e. to Alexander the Great’s conquest of Egypt, 332 BCE). These collections have been largely unstudied, therefore quantifying their extent is particularly difficult. However, we can estimate that the Museum holds c. 12,413 archaeological objects from Egypt and Sudan (some of which were historically recorded on the PRM database as from Nubia)1 that date from this timeframe. This material includes, in addition to objects from Egypt, some 785 database records for artefacts excavated in sites in Nubia under the direction of under the direction of Frances Llewellyn Griffith, the first Professor of Egyptology at the University of Oxford (e.g. Griffith 1921). In a sense, the PRM’s Dynastic Egyptian and Sudanese collections can be characterized overall as ‘small finds’: from funerary objects like shabtis to the excavated artefacts of daily life – such as flint tools, sandals and textiles – which are often illustrative of particular technologies. Little in the collection fits traditional definitions of Egyptian art, such as statuary or relief sculpture. While ‘art objects’ were highly prized by institutions such as the British Museum and the Ashmolean Museum, they stood outside Pitt-Rivers’ original aims for the collection and the character of its subsequent development. -

Abusir and Saqqara in the Year 2015 Sa Qq a R a Nd Abusir Ye a R 2015 in the a Čí Árt Oppens V B Ír Kre J (Editors) (Editors) Ro M Filip C Filip a J Mirosl A

Miroslav Bárta / Filip Coppens / Jaromír Krejčí (editors) A ABUSIR AND SAQQARA R A IN THE YEAR 2015 QQ SA R 2015 A ND A ABUSIR YE IN THE A ČÍ J ÁRT B OPPENS V C ÍR KRE A (EDITORS) (EDITORS) M RO FILIP FILIP A J MIROSL ISBN 978-80-7308-758-6 FA CULTY OF ARTS, C H A RLES U NIVERSITY AS_vstupy_i_xxiv_ABUSIR 12.1.18 13:34 Stránka i ABUSIR AND SAQQARA IN THE YEAR 2015 AS_vstupy_i_xxiv_ABUSIR 12.1.18 13:34 Stránka ii ii Table Contens The publication was compiled within the framework of the Charles University Progress project Q11 – “Complexity and resilience. Ancient Egyptian civilisation in multidisciplinary and multicultural perspective”. AS_vstupy_i_xxiv_ABUSIR 12.1.18 13:34 Stránka iii Table Contens iii ABUSIR AND SAQQARA IN THE YEAR 2015 Miroslav Bárta – Filip Coppens – Jaromír Krejčí (editors) Faculty of Arts, Charles University Prague 2017 AS_vstupy_i_xxiv_ABUSIR 12.1.18 13:34 Stránka iv iv Table Contens Reviewers Ladislav Bareš, Nigel Strudwick Contributors Katarína Arias Kytnarová, Miroslav Bárta, Edith Bernhauer, Vivienne Gae Callender, Filip Coppens, Jan-Michael Dahms, Vassil Dobrev, Veronika Dulíková, Andres Diego Espinel, Laurel Flentye, Zahi Hawass, Jiří Janák, Peter Jánosi, Lucie Jirásková, Mohamed Ismail Khaled, Evgeniya Kokina, Jaromír Krejčí, Elisabeth Kruck, Hella Küllmer, Audran Labrousse, Renata Landgráfová, Rémi Legros, Radek Mařík, Émilie Martinet, Mohamed Megahed, Diana Míčková, Hassan Nasr el-Dine, Hana Navratilová, Massimiliano Nuzzolo, Martin Odler, Adel Okasha Khafagy, Christian Orsenigo, Robert Parker, Stephane Pasquali, Dominic Perry, Marie Peterková Hlouchová, Patrizia Piacentini, Gabriele Pieke, Maarten J. Raven, Joanne Rowland, Květa Smoláriková, Saleh Soleiman, Anthony J. -

Report on the Season 2003—2004 of the Czech Archaeological Mission

ABUSIR Archaeological season of 2003 – 2004 Czech Institute of Egyptology Charles University, Prague ABUSIR Archaeological season of 2003 – 2004 Czech Institute of Egyptology In accordance with the permission granted by the Permanent Committee of the Supreme Council of Antiquities, Egypt, the Czech Institute of Egyptology´s expedition carried out an archaeological season at Abusir. The season lasted from early September 2003 through mid April 2004. Expedition members: Prof. M. Verner, Direktor of the expedition Eng. M. Balík, architekt Ass. Prof. L. Bareš, Egyptologist H. Benešovská, MA, Egyptologist Eng. V. Brůna, surveyor Dr. V. Callender, Egyptologist Eng. M. Dvořák, conservator Dr. Salima Ikram, Egyptologist Dr. Jana Kotková, petrologist Dr. J. Krejčí, Egyptologist R. Landgráfová, MA., Egyptologist Dr. D. Magdolen, Egyptologist J. Mynářová, MA, Egyptologist Dr. W.-B. Oerter, Coptologist Ass. Prof. M. Procházka, surveyor Dr. K. Smoláriková, Egyptologist Prof. E. Strouhal, anthropologist Ass. Prof. J. Svoboda, archaeologist Ass. Prof. B. Vachala, Egyptologist P. Vlčková, MA, Egyptologist K. Voděra, photographer H. Vymazalová, MA, Egyptologist SCA inspectors : Abd el-Hamid Abu el-Ghaffar Amir Nabil Mohammad Azzam Ahmad Salama Mahruz Eid Mustafa Mustafa Hasan Abd Er-Rahman Foremen of workmen: Mohammed el-Kereti Ahmed el-Kereti – 2 – 1. Pyramid Complex Lepsius No. 25 The pyramid complex Lepsius No. 25 is an extraordinary complex consisting of two tombs in the shape of truncated pyramids built closely beside each other on the southern edge of Abusir pyramid plateau. During this season, the excavation of this twin tomb was mostly focussed on the eastern of the two pyramids. Under the layers of wind blown sand and stone rubble, partly removed already during the season of 2000—2001, the remnants of the white limestone walls of the funerary apartment were revealed. -

Pathography of Lady Imakhetkherresnet, Sister of Priest Iufaa

Izvorni rad Acta med-hist Adriat 2007;5(2);173-188 Original paper UDK: 616-092:569.9>(32) PATHOGRAPHY OF LADY IMAKHETKHERRESNET, SISTER OF PRIEST IUFAA PATOGRAFIJA IMAKHETKHERRESNET, SESTRE SVEĆENIKA IUFAAE Eugen Strouhal 1, Alena Němečková 2, Fady Khattar 3 ABSTRACT Lady Imakhetkherresnet was buried at the age of 35-45 years in the southern corridor of a well preserved shaft tomb of priest Iufaa at Abusir (end 26 th Dynasty, 625 BC). The tomb was excavated by the Czech Institute of Egyptology from 1994 to 2004. Morphometric, genetic and epigenetic features linked her by blood to Iufaa; epigraphic evidence concluded that she was his sister. Her pathography includes the usual tooth diseases, and early stage vertebral osteophyto- sis and degenerative osteoarthritis. She also suffered a spiral fracture of both right lower leg bones. A large smooth-walled cavity was found in her sacrum, moulded by the pressure of a relatively hard tissue mass. Its extent and lobulated form were first assessed macroscopi- cally and then by standard radiography. CT sections revealed wide cavities extending from the spinal canal to both 2 nd sacral foramina and to the left 3rd sacral body. A benign neurilemmoma was diagnosed by macroscopy and radiography, and confirmed by histology. This benign tumour is the first of its kind and localization to be identified in palaeopathology and in the history of medicine. Keywords: pathography, bone and tooth diseases, neurilemmoma, Abusir, 26th dynas- ty, Egypt 1 Institute for the History of Medicine and Foreign Languages, First Medical Faculty, Charles University Prague 2 Institute for Histology and Embryology, Medical Faculty Pilsen, Charles University Prague 3 National Cancer Institute, Cairo University, Cairo, Egyptian Arab Republic Corresponding author: Prof., DrSc.