The Failings of Intellectual Property Law Through the Eyes of Superman

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Members' Arts Programs in CMSD Schools 2016-2017 76 Responses

Members’ Arts Programs in CMSD Schools 2016-2017 Cleveland Arts Education Consortium invited its members to participate in a survey to learn which schools in the Cleveland Metropolitan School District were served by arts organizations during one academic year. 76 responses (85%) of 90 invited to participate 17 Organizations checked “We served No CMSD Schools in 2016-2017” Of the 17 organizations, 12 are open to serving CMSD Schools in the future. Of the 17 organizations, 5 have no plans* to do so in the future. * Some CAEC members provide arts education programs in out of school time settings, or in non-CMSD Schools and other communities. “Yes, we are willing and able to serve CMSD schools, but have not had the opportunity to do so. Instead, we have been teaching in schools in other school districts outside of CMSD.” Following is a list of CAEC Member Organization CMSD Contacts 2016-2017 CAEC Member Organization CMSD Contacts 2016-2017 Elementary Schools PreK-8 or K-8 High Schools (9-12) plus K-12 and Block Scheduled Charter Schools Elementary PreK-8 or K- & HS # of Contacts Schools Building Type 25 Cleveland School of the Arts Elementary/High School (PreK-12) 20 Campus International Elementary PreK-8 or K-8 17 Franklin D. Roosevelt Elementary PreK-8 or K-8 15 Newton D. Baker School of the Arts Elementary PreK-8 or K-8 14 John Adams High School High School (9-12) 13 Luis Munoz Marin Elementary PreK-8 or K-8 13 Marion-Sterling Elementary PreK-8 or K-8 12 Bolton Elementary PreK-8 or K-8 12 Lincoln-West High School High School (9-12) 12 Thomas Jefferson International Newcomers Academy Elementary/High School (PreK-12) 11 Adlai E. -

Copyright 2013 Shawn Patrick Gilmore

Copyright 2013 Shawn Patrick Gilmore THE INVENTION OF THE GRAPHIC NOVEL: UNDERGROUND COMIX AND CORPORATE AESTHETICS BY SHAWN PATRICK GILMORE DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2013 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Professor Michael Rothberg, Chair Professor Cary Nelson Associate Professor James Hansen Associate Professor Stephanie Foote ii Abstract This dissertation explores what I term the invention of the graphic novel, or more specifically, the process by which stories told in comics (or graphic narratives) form became longer, more complex, concerned with deeper themes and symbolism, and formally more coherent, ultimately requiring a new publication format, which came to be known as the graphic novel. This format was invented in fits and starts throughout the twentieth century, and I argue throughout this dissertation that only by examining the nuances of the publishing history of twentieth-century comics can we fully understand the process by which the graphic novel emerged. In particular, I show that previous studies of the history of comics tend to focus on one of two broad genealogies: 1) corporate, commercially-oriented, typically superhero-focused comic books, produced by teams of artists; 2) individually-produced, counter-cultural, typically autobiographical underground comix and their subsequent progeny. In this dissertation, I bring these two genealogies together, demonstrating that we can only truly understand the evolution of comics toward the graphic novel format by considering the movement of artists between these two camps and the works that they produced along the way. -

Superman's Girl Friend, Lois Lane and the Represe

Research Space Journal article ‘Superman believes that a wife’s place is in the home’: Superman’s girl friend, Lois Lane and the representation of women Goodrum, M. Canterbury Christ Church University’s repository of research outputs http://create.canterbury.ac.uk Please cite this publication as follows: Goodrum, M. (2018) ‘Superman believes that a wife’s place is in the home’: Superman’s girl friend, Lois Lane and the representation of women. Gender & History, 30 (2). ISSN 1468-0424. Link to official URL (if available): https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0424.12361 This version is made available in accordance with publishers’ policies. All material made available by CReaTE is protected by intellectual property law, including copyright law. Any use made of the contents should comply with the relevant law. Contact: [email protected] ‘Superman believes that a wife’s place is in the home’: Superman’s Girl Friend, Lois Lane and the representation of women Michael Goodrum Superman’s Girl Friend, Lois Lane ran from 1958-1974 and stands as a microcosm of contemporary debates about women and their place in American society. The title itself suggests many of the topics about which women were concerned, or at least were supposed to concern them: the mediation of identity through heterosexual partnership, the pressure to marry and the simultaneous emphasis placed on individual achievement. Concerns about marriage and Lois’ ability to enter into it routinely provide the sole narrative dynamic for stories and Superman engages in different methods of avoiding the matrimonial schemes devised by Lois or her main romantic rival, Lana Lang. -

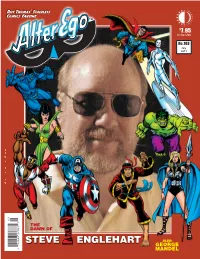

Englehart Steve

AE103Cover FINAL_AE49 Trial Cover.qxd 6/22/11 4:48 PM Page 1 BOOKS FROM TWOMORROWS PUBLISHING Roy Thomas’ Stainless Comics Fanzine $7.95 In the USA No.103 July 2011 STAN LEE UNIVERSE CARMINE INFANTINO SAL BUSCEMA MATT BAKER The ultimate repository of interviews with and PENCILER, PUBLISHER, PROVOCATEUR COMICS’ FAST & FURIOUS ARTIST THE ART OF GLAMOUR mementos about Marvel Comics’ fearless leader! Shines a light on the life and career of the artistic Explores the life and career of one of Marvel Comics’ Biography of the talented master of 1940s “Good (176-page trade paperback) $26.95 and publishing visionary of DC Comics! most recognizable and dependable artists! Girl” art, complete with color story reprints! (192-page hardcover with COLOR) $39.95 (224-page trade paperback) $26.95 (176-page trade paperback with COLOR) $26.95 (192-page hardcover with COLOR) $39.95 QUALITY COMPANION BATCAVE COMPANION EXTRAORDINARY WORKS IMAGE COMICS The first dedicated book about the Golden Age Unlocks the secrets of Batman’s Silver and Bronze OF ALAN MOORE THE ROAD TO INDEPENDENCE publisher that spawned the modern-day “Freedom Ages, following the Dark Knight’s progression from Definitive biography of the Watchmen writer, in a An unprecedented look at the company that sold Fighters”, Plastic Man, and the Blackhawks! 1960s camp to 1970s creature of the night! new, expanded edition! comics in the millions, and their celebrity artists! (256-page trade paperback with COLOR) $31.95 (240-page trade paperback) $26.95 (240-page trade paperback) $29.95 (280-page trade -

Crossmedia Adaptation and the Development of Continuity in the Dc Animated Universe

“INFINITE EARTHS”: CROSSMEDIA ADAPTATION AND THE DEVELOPMENT OF CONTINUITY IN THE DC ANIMATED UNIVERSE Alex Nader A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS May 2015 Committee: Jeff Brown, Advisor Becca Cragin © 2015 Alexander Nader All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Jeff Brown, Advisor This thesis examines the process of adapting comic book properties into other visual media. I focus on the DC Animated Universe, the popular adaptation of DC Comics characters and concepts into all-ages programming. This adapted universe started with Batman: The Animated Series and comprised several shows on multiple networks, all of which fit into a shared universe based on their comic book counterparts. The adaptation of these properties is heavily reliant to intertextuality across DC Comics media. The shared universe developed within the television medium acted as an early example of comic book media adapting the idea of shared universes, a process that has been replicated with extreme financial success by DC and Marvel (in various stages of fruition). I address the process of adapting DC Comics properties in television, dividing it into “strict” or “loose” adaptations, as well as derivative adaptations that add new material to the comic book canon. This process was initially slow, exploding after the first series (Batman: The Animated Series) changed networks and Saturday morning cartoons flourished, allowing for more opportunities for producers to create content. References, crossover episodes, and the later series Justice League Unlimited allowed producers to utilize this shared universe to develop otherwise impossible adaptations that often became lasting additions to DC Comics publishing. -

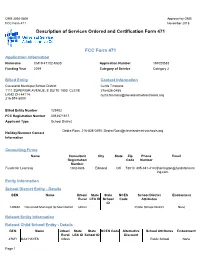

Description of Services Ordered and Certification Form 471 FCC Form

OMB 3060-0806 Approval by OMB FCC Form 471 November 2015 Description of Services Ordered and Certification Form 471 FCC Form 471 Application Information Nickname CM19-47102-MIBS Application Number 191020583 Funding Year 2019 Category of Service Category 2 Billed Entity Contact Information Cleveland Municipal School District Curtis Timmons 1111 SUPERIOR AVENUE, E SUITE 1800 CLEVE 216-838-0485 LAND OH 44114 [email protected] 216-574-8000 Billed Entity Number 129482 FCC Registration Number 0012671517 Applicant Type School District Dedra Ross, 216-838-0495, [email protected] Holiday/Summer Contact Information Consulting Firms Name Consultant City State Zip Phone Email Registration Code Number Number Funds for Learning 16024808 Edmond OK 73013 405-341-4140 jharrington@fundsforlearn ing.com Entity Information School District Entity - Details BEN Name Urban/ State State NCES School District Endowment Rural LEA ID School Code Attributes ID 129482 Cleveland Municipal School District Urban Public School District None Related Entity Information Related Child School Entity - Details BEN Name Urban/ State State NCES Code Alternative School Attributes Endowment Rural LEA ID School ID Discount 47671 MAX HAYES Urban Public School None Page 1 BEN Name Urban/ State State NCES Code Alternative School Attributes Endowment Rural LEA ID School ID Discount 47673 MARION C. SELTZER Urban Public School None 47676 JOSEPH M. GALLAGHER Urban Public School None 47677 WAVERLY Urban Public School None 47682 H. BARBARA BOOKER Urban Public School None MONTESSORI 47683 CLARK Urban Public School None 47684 ALMIRA Urban Public School None 47687 CASE Urban Public School None 47691 WILLSON Urban Public School None 47695 WADE PARK Urban Public School None 47699 MARY B. -

How Superman Developed Into a Jesus Figure

HOW SUPERMAN DEVELOPED INTO A JESUS FIGURE CRISIS ON INFINITE TEXTS: HOW SUPERMAN DEVELOPED INTO A JESUS FIGURE By ROBERT REVINGTON, B.A., M.A. A Thesis Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts McMaster University © Copyright by Robert Revington, September 2018 MA Thesis—Robert Revington; McMaster University, Religious Studies McMaster University MASTER OF ARTS (2018) Hamilton, Ontario, Religious Studies TITLE: Crisis on Infinite Texts: How Superman Developed into a Jesus Figure AUTHOR: Robert Revington, B.A., M.A (McMaster University) SUPERVISOR: Professor Travis Kroeker NUMBER OF PAGES: vi, 143 ii MA Thesis—Robert Revington; McMaster University, Religious Studies LAY ABSTRACT This thesis examines the historical trajectory of how the comic book character of Superman came to be identified as a Christ figure in popular consciousness. It argues that this connection was not integral to the character as he was originally created, but was imposed by later writers over time and mainly for cinematic adaptations. This thesis also tracks the history of how Christians and churches viewed Superman, as the film studios began to exploit marketing opportunities by comparing Superman and Jesus. This thesis uses the methodological framework of intertextuality to ground its treatment of the sources, but does not follow all of the assumptions of intertextual theorists. iii MA Thesis—Robert Revington; McMaster University, Religious Studies ABSTRACT This thesis examines the historical trajectory of how the comic book character of Superman came to be identified as a Christ figure in popular consciousness. Superman was created in 1938, but the character developed significantly from his earliest incarnations. -

MAY 4 Quadracci Powerhouse

APRIL 8 – MAY 4 Quadracci Powerhouse By David Bar Katz | Directed by Mark Clements Judy Hansen, Executive Producer Milwaukee Repertory Theater presents The History of Invulnerabilty PLAY GUIDE • Play Guide written by Lindsey Hoel-Neds Education Assistant With contributions by Margaret Bridges Education Intern • Play Guide edited by Jenny Toutant Education Director MARK’S TAKE Leda Hoffmann “I’ve been hungry to produce History for several seasons. Literary Coordinator It requires particular technical skills, and we’ve now grown our capabilities such that we can successfully execute this Lisa Fulton intriguing exploration of the life of Jerry Siegel and his Director of Marketing & creation, Superman. I am excited to build, with my wonder- Communications ful creative team, a remarkable staging of this amazing play that will equally appeal to theater-lovers and lovers of comic • books and superheroes.”” -Mark Clements, Artistic Director Graphic Design by Eric Reda TABLE OF CONTENTS Synopsis ....................................................................3 Biography of Jerry Siegel. .5 Biography of Superman .....................................................5 Who’s Who in the Play .......................................................6 Mark Clements The Evolution of Superman. .7 Artistic Director The Golem Legend ..........................................................8 Chad Bauman The Übermensch ............................................................8 Managing Director Featured Artists: Jef Ouwens and Leslie Vaglica ...............................9 -

Cross Fire: an Original Companion Novel (Batman Vs. Superman: Dawn of Justice) Free

FREE CROSS FIRE: AN ORIGINAL COMPANION NOVEL (BATMAN VS. SUPERMAN: DAWN OF JUSTICE) PDF Michael Kogge | 144 pages | 16 Feb 2016 | Scholastic Inc. | 9780545916301 | English | United States Cross Fire: An Original Companion Novel of Batman v Superman: Dawn of Justice – DC Comics Movie It was released on February 16, After saving Metropolis from an alien invasion, Superman is now famous around the world. Meanwhile Gotham City 's own guardian, Batman, would rather fight crime from the shadows. But when the devious Doctor Aesop escapes from Arkham Asylumthe two very different heroes begin investigating the same case and a young boy is caught in the cross fire. The book also includes a full-color insert with images from the feature film. Two weeks after the Battle of Metropolisschoolboy Rory Greeley has been searching for his mother, who has been missing since the Black Zero Event. Instead of informing the authorities of this, he has for the past two weeks been working on a remote controlled drone to search the rubble for her. Superman has been assisting rescue workers by clearing rubble and rescuing trapped civilians since General Zod was defeated. Also a telethon run by the Metropolis News Network is happening that night, to raise money for Cross Fire: An Original Companion Novel (Batman vs. Superman: Dawn of Justice) victims of the attack and help with rebuilding the city. Since the attack, criminals had moved from Metropolis to Gotham out of fear for their lives. Bruce was going to the telethon that night, hoping to raise money for the victims of the event. -

Superman Ebook, Epub

SUPERMAN PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Jerry Siegel | 144 pages | 30 Jun 2009 | DC Comics | 9781401222581 | English | New York, NY, United States Superman PDF Book The next event occurs when Superman travels to Mars to help a group of astronauts battle Metalek, an alien machine bent on recreating its home world. He was voiced in all the incarnations of the Super Friends by Danny Dark. He is happily married with kids and good relations with everyone but his father, Jor-EL. American photographer Richard Avedon was best known for his work in the fashion world and for his minimalist, large-scale character-revealing portraits. As an adult, he moves to the bustling City of Tomorrow, Metropolis, becoming a field reporter for the Daily Planet newspaper, and donning the identity of Superman. Superwoman Earth 11 Justice Guild. James Denton All-Star Superman Superman then became accepted as a hero in both Metropolis and the world over. Raised by kindly farmers Jonathan and Martha Kent, young Clark discovers the source of his superhuman powers and moves to Metropolis to fight evil. Superman Earth -1 The Devastator. The next few days are not easy for Clark, as he is fired from the Daily Planet by an angry Perry, who felt betrayed that Clark kept such an important secret from him. Golden Age Superman is designated as an Earth-2 inhabitant. You must be a registered user to use the IMDb rating plugin. Filming on the series began in the fall. He tells Atom he is welcome to stay while Atom searches for the people he loves. -

Read Book Smallville: Season 5 : the Official Companion

SMALLVILLE: SEASON 5 : THE OFFICIAL COMPANION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Craig Byrne | 160 pages | 25 Jan 2008 | Titan Books Ltd | 9781845765422 | English | London, United Kingdom Smallville: Season 5 : The Official Companion PDF Book Cassandra rated it it was amazing Jul 05, Every episode is well examined, and some episodes, like the popular "Memoria," were treated with extended sections. According to writers Kelly Souders and Brian Peterson, "Reckoning" had been chosen as the episode's title before the script had been finalized. Karen A. One faction of fans was unhappy with the choice of Jonathan, however, as they would have preferred Lana dying instead. Volume 5 - 1st printing. Alongside E4 broadcasting the new series of the show, Sci-Fi were also broadcasting all the older episodes, which ran all the way up to the end of Season 7. However, the show was not able to afford the special effects to pull the scene off, and so, the sequence was re-written to feature a bus crash. Leslie rated it it was amazing Jun 26, This authorized companion with a stunning page full-color section takes you through Season Four, which achieved the highest ratings of any season! Since then, she has headlined shows like Bitten and the reboot of V. The final version was finished "two-and-a-half [to] three weeks" before production began. It should come as no surprise, then, that Durance was a hit with the viewers and fans and she remains one of the, if not the best incarnation of Lois Lane there ever has been highly contentious though that sentence is. -

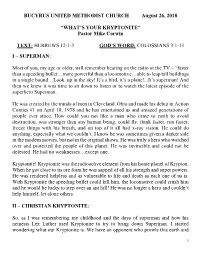

What's Your Kryptonite

BUCYRUS UNITED METHODIST CHURCH August 26, 2018 “WHAT’S YOUR KRYPTONITE” Pastor Mike Corwin TEXT: HEBREWS 12:1-3 GOD’S WORD: COLOSSIANS 3:1-11 I – SUPERMAN: Most of you, my age or older, will remember hearing on the radio or the TV – “faster than a speeding bullet…more powerful than a locomotive…able to leap tall buildings in a single bound…Look, up in the sky! It’s a bird, it’s a plane!...It’s superman! And then we knew it was time to sit down to listen or to watch the latest episode of the superhero Superman. He was created by the minds of men in Cleveland, Ohio and made his debut in Action Comics #1 on April 18, 1938 and he has entertained us and amazed generations of people ever since. How could you not like a man who came to earth to avoid destruction, was stronger than any human being, could fly, think faster, run faster, freeze things with his breath, and on top of it all had x-ray vision. He could do anything, especially what we couldn’t. I know he was sometimes given a darker side in the modern movies, but not in the original shows. He was truly a hero who watched over and protected the people of this planet. He was invincible and could not be defeated. He had no weaknesses…except one. Kryptonite! Kryptonite was the radioactive element from his home planet of Krypton. When he got close to its ore form he was sapped of all his strength and super powers.